Bison

| Bison | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

American bison | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||||

|

B. bison |

Bison are members of the genus Bison of the Bovid family of the even-toed ungulates, or hoofed mammals. There are two extant (living) species of bison:

- The American bison (Bison bison), the most famous bison, formerly one of the most common large animals in North America

- The European bison or wisent (Bison bonasus)

There are two extant subspecies of the American bison, the Plains bison (Bison bison bison) and the wood bison (Bison bison athabascae). There were also several other species and subspecies of bison that became extinct within the last 10,000 years.

Bison were once very numerous in North America and Europe, but overhunting resulted in their near extinction. The American bison was reduced from herds of about 30 million in the 1500s to about 1,000 individuals, and the wisent was reduced to fewer than 50 animals, all in zoos. Today, both species have been managed to significant recoveries.

Bison are often called buffalo in North America, but this is technically incorrect since true buffalo are native only to Asia (water buffalo) and Africa (African buffalo). Bison are very closely related to true buffalo, as well as cattle, yaks, and other members of the subfamily Bovinae, or bovines.

Bison physiology and behavior

Bison are among the largest hoofed mammals, standing 1.5 to 2 meters (5 to 6.5 feet) at the shoulder and weighing 350 to 1000 kg (800 to 2,200 lbs). Males are on average larger than females. The head and forequarters of bison are especially massive with a large hump on the shoulders. Both sexes have horns with the male's being somewhat larger (Nowak 1983).

Bison mature in about two years and have an average life span of about twenty years. A female bison can have a calf every year, with mating taking place in summer and birth in spring, when conditions are best for the young animal. Bison are "polygynous": dominant bulls maintain a small harem of females for mating. Male bison fight with each other over the right to mate with females. The male bison's greater size, larger horns, and thicker covering of hair on the head and front of the body benefit them in these struggles. In many cases the smaller, younger, or less confident male will back down and no actual fight will take place (Lott 2002).

The bison's place in nature

Bison are strictly herbivores. American bison, which live mainly in grasslands, are grazers, while European bison, living mainly in forests, are browsers. American bison migrate over the grassland to reach better conditions. In the past, herds of millions traveled hundreds of miles seasonally to take advantage of different growing conditions. This gives the grass a chance to recover and regrow. The bison’s droppings and urine fertilize the soil, returning needed nitrogen (Lott 2002).

Bison are subject to various parasites, among them the winter tick, Dermacentor albipictus, a single one of which can reduce a calf's growth by 1.5 lbs (.7 kg) due to the blood it takes. Bison roll in dirt in order to remove ticks and other parasites. This also helps them to keep cool in hot weather (Lott 2002).

One animal that has a mutually beneficial, symbiotic relationship with the American bison is the black-tailed prairie dog, Cynomys ludovicianus, a small rodent. Prairie dogs eat the same grass as the bison and live in large groups in underground tunnels called "towns." Bison are attracted to prairie dog towns by the large mounds of dirt removed from the tunnels, which the bison use to roll in. The bison benefit the prairie dogs by eating the tall grass and fertilizing the soil, both of which promote the growth of the more nutritious, short grass (Lott 2002).

Because of their large size and strength, bison have few predators. In both North America and Europe, wolves, Canis lupus, are (or were) the most serious predator of bison (besides humans). The wolves' habit of hunting in groups enables them to prey on animals much larger than themselves. But most often it is the calves that fall victim to wolves. It has been suggested that the bison's tendency to run away from predators, rather than standing and fighting like many other bovines (including possibly the extinct bison species) has given them a better chance against wolves, and later human hunters. The brown bear (Ursus arctos), called the grizzly bear in North America, also eats bison, but is too slow to catch healthy, alert adult bison, so it mainly eats those that have died from cold or disease (Lott 2002).

American Bison

The American Bison (Bison bison) is the largest terrestrial mammal in North America.

The American bison's two subspecies are the Plains bison (Bison bison bison), distinguished by its smaller size and more rounded hump, and the wood bison (Bison bison athabascae), distinguished by its larger size and taller square hump. With their huge bulk, wood bison are only surpassed in size by the massive Asian gaur and wild water buffalo, both of which are found mainly in India.

One very rare condition results in the white buffalo, where the calf turns entirely white. It is not to be confused with albino, since white bison still possess pigment in the skin, hair, and eyes. White bison are considered sacred by many Native Americans.

Wisent

The wisent or European bison (Bison bonasus) is the heaviest land animal in Europe. A typical wisent is about 2.9 m long and 1.8–2 m tall, and weighs 300 to 1000 kg. It is typically lankier and less massive than the related American bison (B. bison), and has shorter hair on the neck, head, and forequarters. Wisents are forest-dwelling. Wisents were first scientifically described by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758. Some later descriptions treat the wisent as conspecific with the American bison. It is not to be confused with the aurochs.

Three sub-species have been identified, two of which are extinct:

- Lowland wisent – Bison bonasus bonasus (Linneus, 1758)

- Hungarian (Carpathian) wisent – Bison bonasus hungarorum – extinct

- Caucasus wisent – Bison bonasus caucasicus – extinct

Wisents have lived as long as 28 years in captivity, although in the wild their lifespan is shorter. Productive breeding years are between the ages of four and 20 years in females and only between the ages of 6 and 12 years in males. Wisents occupy home ranges of as much as 100 square kilometers and some herds are found to prefer meadows and open areas in forests.

Wisents can cross-breed with American bison. There are also bison–wisent–cattle hybrids.

Bison and humans

Bison were once very plentiful and an important prey for human hunters from prehistoric times. However, by the nineteenth century, both the American bison and the European bison were nearly extinct, largely as a result of human hunting.

In North America, it is estimated that there were about 30 million bison in the 1500s, when they were hunted by Native Americans. The National Bison Association lists over 150 traditional Native American uses for bison products, besides food (NBA 2006). The introduction of the horse to North America in the 1500s made hunting bison easier. Bison became even more important to some Native American tribes living on the Great Plains.

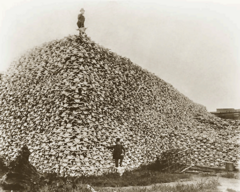

As Americans of European descent moved into Native American lands, the bison were significantly reduced through overhunting. Some of the reasons for this were to free land for agriculture and cattle ranching, to sell the hides of the bison, to deprive hostile tribes of their main food supply, and for what was considered sport. The worst of the killing took place in the 1870s and the early 1880s. By 1890, there were fewer than 1,000 bison in North America (Nowak 1983).

One major cause of the near extinction of the American bison was because of overhunting as a result of commercial hunters being paid by large railroad concerns to destroy entire herds, for several reasons:

- The herds formed the basis of the economies of local Plains tribes of Native Americans; without bison, the tribes would leave.

- Herds of these large animals on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop them in time.

- Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding though hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions. As a result, the herds could delay a train for days.

Bison skins were used for industrial machine belts, clothing such as robes, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, cartridge reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and recast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters, such as Buffalo Bill Cody (who later advocated for protection of the bison) killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their career. A good hide could bring $3.00 in Dodge City, Kansas, and a very good one (the heavy winter coat) could sell for $50.00 in an era when a laborer would be lucky to make a dollar a day.

The American bison has made a comeback with about 20,000 living in the wild in parks and preserves, including Yellowstone National Park, and about 500,000 living on ranches and tribal lands where they are managed, although not domesticated. Bison ranching continues to expand yearly, with bison raised for meat and hides. Bison meat has grown in popularity, partly because of its lower fat and higher iron and vitamin B12 content compared to beef (NBA 2006). Because it is lower in both fat and cholesterol than beef, bison and domestic cattle have been crossbred, creating beefalo.

The wood bison, a subspecies of the American bison, had been reduced to about 250 animals by 1900, but has now recovered to about 9,000, living mainly in northwest Canada.

The European bison was also hunted almost to extinction, with wisents limited to fewer than 50 individuals by 1927, when they were only found in zoos. In the Middle Ages, they were commonly killed to produce hides and drinking horns. In western Europe, wisent were extinct by the eleventh century, except in the Ardennes, where they lasted into the fourteenth century. The last wisent in Transylvania died in 1790. In the east, wisents were legally the property of the Polish kings, Lithuanian princes, and Russian tsars. King Sigismund the Old of Poland instituted the death penalty for poaching a wisent in the mid-1500s. Despite these and other measures, the wisent population continued to decline over the following four centuries. The last wild wisent in Poland was killed in 1919, and the last wild wisent in the world was killed by poachers in 1927 in the Western Caucasus. By that year fewer than 50 remained, all in zoos.

Wisents were reintroduced successfully into the wild beginning in 1951. They are found free-ranging in forest preserves, like Western Caucasus in Russia and Białowieża Forest in Poland and Belarus. Free-ranging herds are found in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Russia, and Kyrgyzstan. Zoos in 30 countries also have quite a few animals. There were 3,000 individuals as of 2000, all descended from only 12 individuals. Because of their limited genetic pool, they are considered highly vulnerable to diseases like foot-and-mouth disease.

Recent genetic studies of privately owned herds of bison show that many of them include animals with genes from domestic cattle; there are as few as 12,000 to 15,000 pure bison in the world. The numbers are uncertain because the tests so far used mitochondrial DNA analysis, and thus would miss cattle genes inherited in the male line; most of the hybrids look exactly like purebred bison.

For Americans, the bison is an important part of history, a symbol of national identity, and a favorite subject of artists. Many American towns, sports teams, and other organizations use the bison as a symbol, often under the name buffalo. For many Native Americans, the bison holds an even greater importance. Fred DuBray of the Cheyenne River Sioux said: “We recognize the bison is a symbol of our strength and unity, and that as we bring our herds back to health, we will also bring our people back to health" (IBC 2006).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Intertribal Bison Cooperative (IBC). 2006. Website. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- Lott, D. F. 2002. American Bison. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- National Bison Association (NBA). 2006. Website. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- Nowak, R. M., and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, NJ: Plexus Publishing.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.