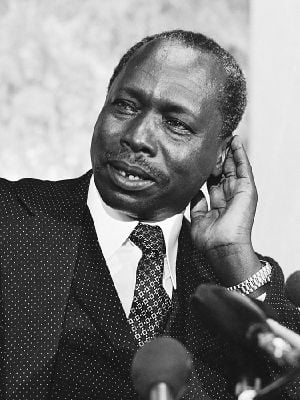

Daniel arap Moi

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi (September 2, 1924 - February 4, 2020) was the President of Kenya from 1978 until 2002. He entered Parliament in 1955, serving as Education Minister in the first post independence government. By 1964, he was Minister for Home Affairs and by 1967, Vice-President of Kenya. He became President following Jomo Kenyatta's death in 1978, running unopposed. In 1982, an attempted coup failed and Moi took the opportunity to consolidate his own position as President, becoming increasingly authoritarian. In 1992, he held multi-party elections for the first time, retaining the Presidency with a plurality of votes (36 percent). Constitutionally prevented him from seeking re-election in 2002 and he stepped down. His hand-picked successor lost to Mwai Kibaki. Moi manipulated the smaller tribes' fear of domination by the larger ones to play different factions against each other. While rewarding his friends and supporters with government posts, he made no attempt to widen participation, or to address the fears he used for his own political advantage.

Daniel arap Moi is popularly known to Kenyans as "Nyayo," a Swahili word for "footsteps." He championed what he called "Nyayo philosophy," which means following the leader and is, he claimed, a distinctive African tradition of leadership. He claimed to be following the footsteps of the first Kenyan President, Jomo Kenyatta. From 1981 until 1983, he Chaired the Organization of African Unity. He always carried a silver-headed ivory stick as an emblem of office (a "rungu" in Swahili.) However, when unable to continue as President he respected the Constitution and stepped aside; he did not attempt to perpetuate his power illegally. Economically, Kenya suffered under his Presidency, due in the main to mismanagement. He did not amass a huge personal fortune but nor did he leave office impoverished, owning seven impressive private residences.[1] While President, Moi helped to mediate several conflict situations and in retirement had an official role in helping to end war in Sudan.

Moi had every right to argue in favor of distinctive African styles of leadership. However, claiming African legitimacy for a style of leadership must not be used as an excuse for despotic, corrupt, autocratic rule that did nothing to raise the living standards of the majority or which denies human rights and civil liberty.

Early life and entry into politics

Moi was born in Kurieng'wo village, Sacho division, Baringo District, Rift Valley Province, and was raised by his mother Kimoi Chebii following the early death of his father. After completing his secondary education, he attended Tambach Teachers Training College in Keiyo District. He worked as a teacher from 1946 until 1955. From 1949, he taught at a Teacher Training College in Kabarnet.

In 1955, Moi entered politics when he was elected Member of the Legislative Council for Rift Valley. In 1960, he founded the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) with Ronald Ngala to challenge the Kenya African National Union (KANU) led by Jomo Kenyatta. KADU's aim was to defend the interests of the small minority tribes, such as the Kalenjin to which Moi belonged, against the dominance of the large Luo and Gĩkũyũ tribes that comprised the majority of KANU's membership (Kenyatta himself being a Gĩkũyũ). KADU pressed for a federal constitution, while KANU was in favor of centralism. The advantage lay with the numerically stronger KANU, and the British government was finally forced to remove all provisions of a federal nature from the constitution.

In 1957, Moi was re-elected Member of the Legislative Council for Rift Valley. The same year he was instrumental in forming the Kenyan Teachers Union. In June 1960, he took part in the Constitutional talks in London. He was outspoken in demanding Kenyatta's release from prison. He became Minister of Education in the pre-independence government of 1960–1961. He then served as Minister for Local Government.

Vice-Presidency

After Kenya gained independence on December 12, 1963, Kenyatta convinced Moi that KADU and KANU should be merged to complete the process of decolonization. Kenya, therefore, became a de facto single-party state, dominated by the Kĩkũyũ-Luo alliance. With an eye on the fertile lands of the rift valley populated by members of Moi's Kalenjin tribe, Kenyatta secured their support by first promoting Moi to Minister for Home Affairs in 1964, and then to vice-president in 1967. As a member of a minority tribe, Moi was also an acceptable compromise for the major tribes. Moi was elected to the Kenyan parliament in 1963, from Baringo North. Since 1966, until his retirement in 2002, he served as the Baringo Central MP.

However, Moi faced opposition from the Kikuyu elite known as the Kiambu Mafia, who would have preferred one of their own to be eligible for the presidency. This resulted in an infamous attempt by the constitutional drafting group to change the constitution to prevent the vice-president automatically assuming power in the event of the president's death. The presence of this succession mechanism may have led to dangerous political instability if Kenyatta died, given his advanced age and perennial illnesses. However, Kenyatta withstood the political pressure and safeguarded Moi's position.

Presidency

Thus, when Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, Moi became president and took the oath of office. He was popular, with widespread support all over the country. He toured the country and came into contact with the people everywhere, which was in great contrast to Kenyatta's imperial style of governing behind closed gates. Political realities, however, dictated that he would continue to be beholden to the Kenyatta system which he had inherited intact, and he was still too weak to consolidate his power. The Kikuyu elite referred to him as "a passing cloud" and a "limping sheep that could not lead other sheep to the pasture," the implication being that he would be pushed aside in a short while to allow them back into power. From the beginning, anticommunism was an important theme of Moi's government; speaking on the new President's behalf, Vice-President Mwai Kibaki bluntly stated, "There is no room for communists in Kenya."[2]

On August 1, 1982, fate played into Moi's hands when forces loyal to his government defeated an attempted coup by Air Force officers led by Hezekiah Ochuka. To this day it appears that the attempt by two independent groups to seize power contributed to the failure of both, with one group making its attempt slightly earlier than the other.

Moi took the opportunity to dismiss political opponents and consolidate his power. He reduced the influence of Kenyatta's men in the cabinet through a long running judicial inquiry that resulted in the identification of key Kenyatta men as traitors. Moi pardoned them but not before establishing their traitor status in the public view. The main conspirators in the coup, including Ochuka, were sentenced to death, marking the last judicial executions in Kenya. He appointed supporters to key roles and changed the constitution to establish a de jure single-party state. In effect, he replaced the privileges enjoyed by the Kikuyu under Kenyatta with the Kelenji, encouraging the smaller tribes' fear of political domination by the larger to consolidate his own power by claiming to protect their interests.

Kenya's academics and other intelligentsia did not accept this and the universities and colleges became the origin of movements that sought to introduce democratic reforms. However, Kenyan secret police infiltrated these groups and many members moved into exile. Marxism could no longer be taught at Kenyan universities. Underground movements, for example, Mwakenya and Pambana, were born.

Moi's regime now faced the end of the Cold War, and an economy stagnating under rising oil prices and falling prices for agricultural commodities. At the same time, the West no longer dealt with Kenya as it had in the past, when it was viewed as a strategic regional outpost against communist influences from Ethiopia and Tanzania. At that time Kenya had received much foreign aid, and the country was accepted as being well governed with Moi as a legitimate leader and firmly in charge. The increasing amount of political repression, including the use of torture, at the infamous Nyayo House torture chambers had been deliberately overlooked. Some of the evidence of these torture cells were to be later exposed in 2003, after Mwai Kibaki became President.[3]

However, a new thinking emerged after the end of the Cold War, and as Moi became increasingly viewed as a despot, aid was withheld pending compliance with economic and political reforms. One of the key conditions imposed on his regime, especially by the United States through fiery ambassador Smith Hempstone, was the restoration of a multi-party system. Moi managed to accomplish this against fierce opposition, single handedly convincing the delegates at the KANU conference at Kasarani in December 1991.

Moi won elections in 1992 and 1997, which were marred by political killings on both sides. Moi skillfully exploited Kenya's mix of ethnic tensions in these contests, with the ever present fear of the smaller tribes being dominated by the larger tribes. In the absence of an effective and organized opposition, Moi had no difficulty in winning. Although it is also suspected that electoral fraud may have occurred, the key to his victory in both elections was a divided opposition.

Pan-African leader

Moi served two consecutive terms as Chair of the Organization of African Unity (1981-1983). He deployed Kenyan troops as part of a number of peace keeping forces both within the African Continent and beyond, namely Chad, Uganda, Namibia, Mozambique, Morocco, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo in Africa and in Iran/Iraq, Kuwait, Yugoslavia, Liberia, Morocco, Angola, Serbia/Croatia, and East Timor outside Africa. He was also involved in helping to mediate a number of conflict situations, including in Uganda, Congo, Somalia, Chad, Sudan, Mozambique, Eritrea/Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Burundi. He served as Chairman of Preferential Trade Area (1989-1990), COMESA (Common Market for East and Southern Africa) (1999-2000 and of several other agencies.

Criticism and corruption allegations

Amnesty International and a special investigation by the United Nations reported human rights abuses in Kenya.[4]

Moi was also implicated in the 1990s Goldenberg scandal and subsequent cover-ups, where the Kenyan government subsidized exports of gold far in excess of the foreign currency earnings of exporters. In this case, the gold was smuggled from Congo, as Kenya has negligible gold reserves. The Goldenberg scandal cost Kenya the equivalent of more than 10 percent of the country's annual GDP.

Half-hearted inquiries that began at the request of foreign aid donors came to nothing during Moi's presidency. Although it appears that the peaceful transfer of power to Mwai Kibaki may have involved an understanding that Moi would not stand trial for offenses committed during his presidency, foreign aid donors reiterated their requests and Kibaki reopened the inquiry. As the inquiry progressed, Moi, his two sons, Philip and Gideon (who became a member of Parliament), and his daughter June, as well as a host of high-ranking Kenyans, were implicated. In bombshell testimony delivered in late July 2003, Treasury Permanent Secretary Joseph Magari recounted that in 1991, Moi ordered him to pay Ksh34.5 million ($460,000) to Goldenberg, contrary to the laws then in force.[5]

In October 2006, Moi was found, by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, to have taken a bribe from a Pakistani businessman to award monopoly of duty free shops at the country's international airport in Mombasa and Nairobi. The businessman, Ali Nasir, claimed to have paid Moi US$2 million in cash to obtain government approval for the World Duty Free Limited investment in Kenya.[6]

Retirement

Moi was constitutionally barred from running in the 2002 presidential elections. Some of his supporters floated the idea of amending the constitution to allow him to run for a third term, but Moi preferred to retire, choosing Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya's first President, as his successor. Mwai Kibaki, was elected President by a two to one majority over Kenyatta, which was confirmed on December 29, 2002. Kibaki was then wheelchair bound having narrowly escaped death in a road traffic accident on the campaign trail. Kibaki had served as Vice-President from 1978 until 1988, then as Minister of Health until 1991, when he left KANU and founded the rival Democratic Party.

Moi handed over power in a poorly organized ceremony that had one of the largest crowds ever seen in Nairobi in attendance. The crowd was openly hostile to Moi.

From that time Moi lived in retirement, largely shunned by the political establishment, but widely popular with the masses, his presence never failing to quickly gather a crowd. He spoke out against the proposed new constitution, terming it a document against the aspirations of the Kenyan people and deciding to vote "No" in the referendum; the referendum was defeated. Kibaki called Moi to arrange for a meeting to discuss the way forward after the defeat. The balance of power would have shifted from President to Parliament.

On July 25, 2007, Kibaki appointed Moi as special peace envoy to Sudan, referring to Moi's "vast experience and knowledge of African affairs" and "his stature as an elder statesman." In his capacity as peace envoy, Moi's primary role was to help secure peace in southern Sudan, where an agreement, signed in early 2005, was being implemented. The Kenyan press speculated that Moi and Kibaki were planning an alliance ahead of the December 2007 election.[7] On August 28, 2007, Moi announced his support for Kibaki's re-election and said that he would campaign for Kibaki. He sharply criticized the two opposition Orange Democratic Movement factions as being tribal in nature.[8]

Personal life

Daniel arap Moi married Lena Moi (born Helena Bommet) in 1950, but they separated in 1974, before his presidency. Thus, "Mama Ngina," the wife of Jomo Kenyatta, retained her first lady status. Lena died in 2004. Daniel arap Moi had eight children, five sons and three daughters. Among the children are Gideon Moi (an MP), Jonathan Toroitich (a former rally driver), and Philip Moi (a retired army officer).[9] His older, and only, brother William Tuitoek died in 1995.[10]

Death

In October 2019, Moi was hospitalized under critical condition at The Nairobi Hospital due to complications of pleural effusion.[11] He was discharged in November 2019, only to be hospitalized again days later for knee surgery.[12]

Daniel arap Moi died at The Nairobi Hospital on the early morning of February 4, 2020 at the age of 95 in the presence of family.[10]

Political philosophy

Moi's "Nyayo" philosophy argues that nationalism in post-colonial Africa requires guidance, since this had not been nurtured under colonial rule. One party democracy was necessary to unify diverse groups into a single nation, and this could best be achieved under a strong, visionary leader. Such leadership could bridge tribal differences and is an African phenomenon that has deep roots in culture and tradition.

The slogans of Nyayo are "peace, love and unity" and a strong centralized state. In 1978, Moi stated that:

In unity and love lies our salvation and strength as a nation. Sectionalism, tribalism, and personality cults are destructive forces which the nation cannot afford today.[13]

At the Madaraka Day Celebrations in 1981 Moi spoke of the vision of Nyayo:

We live now in the era of Nyayo. I hear there are a few people who sometimes seem to wonder just where this Nyayo is leading. Well the answer is simple: towards peace, love and unity. Peace, love and unity are not slogans or vague philosophies: they are practical foundations of countrywide development. Where there is peace, then there is stability and only in the arena of stability will you find investment, enterprise and progress. Where there is love, then there is trust and readiness to work with others to contribute to others in the cause of nationhood. Where there is unity, there is strength, rooted in understanding of our common purposes, common loyalties and mutual dependence.[13]

In his early years in power, he denounced corruption, spoke of the need to "serve wananchi (citizens) to their satisfaction," and as part of this process he reallocated land and introduced several popular reforms, including free primary education and free milk for schoolchildren. He condemned tribalism, although in practice his power was based on manipulating tribal politics.

In 1986, he declared that the Party was "supreme over Parliament and the High Court." Any criticism of government was "viewed as a personal challenge to Moi," which had serious consequences for "free expression, speech and assembly." He developed a personality cult and surrounded himself with sycophants. One commentator has said that Moi had "no faith in Western democracy."[14]

Legacy

Moi's legacy is assessed differently by different people. By some he is considered "a great unifier" and "we owe it to him to cherish the ideals of peace, love and unity."[15]

He believed in homegrown solutions to Africa’s problems and went to great lengths to resolve some of the continent’s most intractable problems including finding peace in South Sudan, Somalia, the civil war and fight for independence in Namibia, among others. Through his efforts, he sought to correct the caricature of Africa as the continent of war, disease, anarchy and poverty. ... it is fair to conclude that through education, Moi set the country on a firm and strong path to growth and progress.[15]

Others stress that he did nothing to reduce tribal tension and left Kenya worse off economically when he left office than it was when he began his Presidency. Phombeah said that "In the 1960s and 70s annual economic growth peaked at 8 percent, but by 2001, it had dropped sharply to -3 percent," and that, "the majority of Kenyans live below the poverty level" with an "average annual income" of "$1 a day."[14]

While Moi's regime has been described as repressive and authoritarian, others have pointed out that he "kept the country united, ended the powerful Kikuyu domination of Kenya's politics and business, and put in place a multi-party system." He was nicknamed "professor of politics" because of his ability to keep "one step ahead of his opponents."[14]

Notes

- ↑ Kamau Ngotho, Moi's golden parachute BBC News, July 30, 2002. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Norman Miller and Rodger Yeager, Kenya: The Quest for Prosperity (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1984, ISBN 9780865310964), 173.

- ↑ Zachary Ochieng, Kenya Torture Chamber Focuses Attention on Abuses of Moi Government - 2003-02-25 Voice of America, October 27, 2009.

- ↑ Korwa G. Adar and Isaac M. Munyae, Human Rights Abuse in Kenya under Daniel Arap Moi 1978-2001, African Studies Quarterly 5:1:1. Retrieved JFebruary 13, 2020.

- ↑ William Karanja, Kenya: Corruption Scandal, World Press Review 50(10) (October 2003). Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Claire Gatheru And Bernard Namunane, Kenya: Country Wins Sh40B Suit As Court Links Moi to Bribery All Africa, October 8, 2006. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ C. Bryson Hull, Kenya names ex-leader Moi special envoy to Sudan Reuters, July 25, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Lucas Barasa and Benjamin Kenya Muindi, Moi endorses Kibaki for Second Term, The Nation, August 28, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Jerry John Rawlings, Rawlings' Speech at the APARC. GhanaWeb, April 15, 2005. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Robert D. McFadden, Daniel arap Moi, Autocratic and Durable Kenyan Leader, Dies at 95 The New York Times, February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Neema Amani, All about the condition former President Moi is being treated for in ICU Mphaso, October 29, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Imende Benjamin, Ex-President Moi rushed back to Nairobi Hospital, again The Star, November 11, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Daniel T. arap Moi, Kenya African Nationalism Nyayo Philosophy and Principles (MacMillan Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0333438176).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Gray Phombeah, Moi's Legacy to Kenya BBC, August 5, 2002. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Peace, love, unity: Moi death has brought out the best in Kenyans Standard Digital. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, S. "Authoritarian leaders and multiparty elections in Africa: How foreign donors help to keep Kenya's Daniel arap Moi in power." Third World Quarterly 22 (2001): 725-740. ISSN 0143-6597

- Colamery, S.N., and Tatiana Shohov. African Leaders: A Bibliography with Indexes. Commack, NY: Nova Science Publishers, 1999. ISBN 978-1560727217

- Maillu, David G. Pragmatic Leadership: Evaluation of Kenya's Cultural and Political Development: Featuring Daniel Arap Moi, President of Republic of Kenya. Nairobi, KE: Maillu Pub. House, 1988.

- Miller, Norman, and Rodger Yeager. Kenya: The Quest for Prosperity. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0865310964

- Moi, Daniel T. arap. Kenya African Nationalism: Nyayo Philosophy and Principles. London: Macmillan, 1986. ISBN 978-0333438718

- Moi, Daniel T. arap, Lee Njiru, and Browne Kutswa. Which way Africa? Nairobi, KE: Govt. Press, 1997. ISBN 978-9966962409

- Morton, Andrew. Moi: The Making of an African Statesman. London: Michael O'Mara, 1998. ISBN 978-1854793690

- Rake, Alan. African Leaders: Guiding the New Millennium. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0810840195

- Russell, Alec. Big Men, Little People: The Leaders who Defined Africa. New York: New York University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0814775424

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.