| Western Philosophy Seventeenth century philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

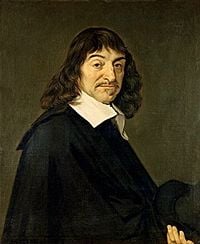

| Name: René Descartes | |

| Birth: March 31, 1596 La Haye en Touraine [now Descartes], Indre-et-Loire, France | |

| Death: February 11 1650 (aged 53) Stockholm, Sweden | |

| School/tradition: Cartesianism, Rationalism, Foundationalism | |

| Main interests | |

| Metaphysics, Epistemology, Science, Mathematics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Cogito ergo sum, method of doubt, Cartesian coordinate system, Cartesian dualism, ontological argument for God's existence; regarded as a founder of Modern philosophy | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Al-Ghazali, Plato, Aristotle, Anselm, Aquinas, Ockham, Suarez, Mersenne, Sextus Empiricus, Michel de Montaigne, Duns Scotus | Spinoza, Hobbes, Arnauld, Malebranche, Pascal, Locke, Leibniz, More, Kant, Husserl, Brunschvicg, ŇĹiŇĺek, Chomsky |

Ren√© Descartes (French IPA: [ Ā…ô'ne de'ka Āt]) (March 31, 1596 ‚Äď February 11, 1650), also known as Renatus Cartesius (latinized form), was a highly influential French philosopher, mathematician, scientist, and writer. He has been dubbed the "Father of Modern Philosophy" and the "Father of Modern Mathematics," and much of subsequent Western philosophy is a reaction to his writings, which have been closely studied from his time through the present day. His influence in mathematics is also apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system that is used in plane geometry and algebra being named for him and he was one of the key figures in the Scientific Revolution.

Descartes frequently sets his views apart from those of his predecessors. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, a treatise on the Early Modern version of what are now commonly called emotions, he goes so far as to assert that he will write on his topic "as if no one had written on these matters before." Many elements of his philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the sixteenth century, or in earlier philosophers like St. Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differs from the Schools on two major points: First, he rejects the analysis of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejects any appeal to ends‚ÄĒdivine or natural‚ÄĒin explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God‚Äôs act of creation.

Descartes was a major figure in seventeenth century continental rationalism, later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza, and Descartes were all versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well. As the inventor of the Cartesian coordinate system, Descartes founded analytic geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry crucial to the invention of calculus and analysis. Descartes's reflections on mind and mechanism began the strain of western thought that much later, impelled by the invention of the electronic computer and by the possibility of machine intelligence, blossomed into the Turing test and related thought. His most famous statement is: Cogito ergo sum (French: Je pense, donc je suis; English: I think, therefore I am), found in §7 of part I of Principles of Philosophy (Latin) and in part IV of Discourse on the Method (French).

Biography

Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine (now Descartes), Indre-et-Loire, France. When he was one year old, his mother Jeanne Brochard died of tuberculosis. His father Joachim was a judge in the High Court of Justice. At the age of eleven, he entered the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche. After graduation, he studied at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat and License in law in 1616, in accordance with his father's wishes that he should become a lawyer.

Descartes never actually practiced law, however, and in 1618, during the Thirty Years' War, he entered the service of Maurice of Nassau, leader of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. His reason for becoming a mercenary was to see the world and to discover the truth.

I entirely abandoned the study of letters. Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth traveling, visiting courts and armies, mixing with people of diverse temperaments and ranks, gathering various experiences, testing myself in the situations which fortune offered me, and at all times reflecting upon whatever came my way so as to derive some profit from it (Descartes, Discourse on the Method).

On November 10, 1618, while walking through Breda, Descartes met Isaac Beeckman, who sparked his interest in mathematics and the new physics, particularly the problem of the fall of heavy bodies. On November 10, 1619, while traveling in Germany and thinking about using mathematics to solve problems in physics, Descartes had a dream through which he "discovered the foundations of a marvelous science."[1] This became a pivotal point in young Descartes's life and the foundation on which he developed analytic geometry. He dedicated the rest of his life to researching this connection between mathematics and nature. Descartes also studied St. Augustine's concept of free will, the belief that human will is essentially equal to God's will; that is, that humans are naturally independent of God's will.

In 1622, he returned to France, and during the next few years spent time in Paris and other parts of Europe. He arrived in La Haye in 1623, selling all of his property, investing this remuneration in bonds which provided Descartes with a comfortable income for the rest of his life. Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627. He left for Holland in 1628, where he lived and changed his address frequently until 1649. Despite this, he managed to revolutionize mathematics and philosophy.

In 1633, Galileo was condemned by the Roman Catholic Church, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish Treatise on the World, his work of the previous four years.

Discourse on the Method was published in 1637. In it an early attempt at explaining reflexes mechanistically is made, although Descartes's theory is later proven wrong within his lifetime.

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes began his long correspondence with Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia. In 1647, he was awarded a pension by the King of France. Descartes was interviewed by Frans Burman at Egmond-Binnen in 1648.

Ren√© Descartes died on February 11, 1650, in Stockholm, Sweden, where he had been invited as a teacher for Queen Christina of Sweden. The cause of death was said to be pneumonia‚ÄĒaccustomed to working in bed until noon, he may have suffered a detrimental effect on his health due to Christina's demands for early morning study (the lack of sleep could have severely compromised his immune system). Others believe that Descartes may have contracted pneumonia as result of nursing a French ambassador, Dejion A. Nopeleen, ill with the aforementioned disease, back to health.[2] In 1663, the Pope placed his works on the Index of Prohibited Books.

As a Roman Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard mainly used for unbaptized infants in Adolf Fredrikskyrkan in Stockholm. Later, his remains were taken to France and buried in the church of Sainte-Geneviève-du-Mont in Paris. His memorial erected in the eighteenth century remains in the Swedish church.

During the French Revolution, his remains were disinterred for burial in the Panth√©on among the great French thinkers. The village in the Loire Valley where he was born was renamed La Haye‚ÄĒDescartes in 1802, which was shortened to "Descartes" in 1967. Currently his tomb is in the church of Saint-Germain-des-Pr√©s in Paris, except for his cranium, which is in the Mus√©e de l'Homme.

Philosophical work

Descartes is often regarded as the first modern thinker to provide a philosophical framework for the natural sciences as they began to develop. He attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called methodological skepticism: he rejects any idea that can be doubted, and then reestablishes them in order to acquire a firm foundation for genuine knowledge.[3] Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single principle: Thought exists. Thought cannot be separated from the thinker, therefore, the thinker exists (Discourse on the Method and Principles of Philosophy). Most famously, this is known as cogito ergo sum (Latin: "I think, therefore I am"), or more aptly, "Dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum" (Latin: "I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am"). Therefore, Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting, therefore the very fact that he doubted proved his existence.[4]

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been proven unreliable. So Descartes concludes that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is his essence as it is the only thing about him that cannot be doubted. Descartes defines "thought" (cogitatio) as "what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it." Thinking is, thus, every activity of a person of which he is immediately conscious.

To further demonstrate the limitations of the senses, Descartes proceeds with what is known as the Wax Argument. He considers a piece of wax: His senses inform him that it has certain characteristics, such as shape, texture, size, color, smell, and so forth. When he brings the wax towards a flame, these characteristics change completely. However, it seems that it is still the same thing: It is still a piece of wax, even though the data of the senses inform him that all of its characteristics are different. Therefore, in order to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he cannot use the senses: He must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

Thus what I thought I had seen with my eyes, I actually grasped solely with the faculty of judgment, which is in my mind.

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception as unreliable and instead admitting only deduction as a method. In the third and fifth Meditation, he offers an ontological proof of a benevolent God (through both the ontological argument and trademark argument). Because God is benevolent, he can have some faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, for God has provided him with a working mind and sensory system and does not desire to deceive him; however, this is a contentious argument, as his very notion of a benevolent God from which he developed this argument is easily subject to the same kind of doubt as his perceptions. From this supposition, however, he finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. In terms of epistemology therefore, he can be said to have contributed such ideas as a rigorous conception of foundationalism and the possibility that reason is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge.

In Descartes's system, knowledge takes the form of ideas, and philosophical investigation is the contemplation of these ideas. This concept would influence subsequent internalist movements, as Descartes's epistemology requires that a connection made by conscious awareness will distinguish knowledge from falsity. As a result of his Cartesian doubt, he sought for knowledge to be "incapable of being destroyed," in order to construct an unshakable ground upon which all other knowledge can be based. The first item of unshakable knowledge that Descartes argues for is the aforementioned cogito, or thinking thing.

Descartes also wrote a response to skepticism about the existence of the external world. He argues that sensory perceptions come to him involuntarily, and are not willed by him. They are external to his senses, and according to Descartes, this is evidence of the existence of something outside of his mind, and thus, an external world. Descartes goes on to show that the things in the external world are material by arguing that God would not deceive him as to the ideas that are being transmitted, and that God has given him the "propensity" to believe that such ideas are caused by material things.

Dualism

Descartes suggested that the body works like a machine, that it has the material properties of extension and motion, and that it follows the laws of physics. The mind (or soul), on the other hand, was described as a nonmaterial entity that lacks extension and motion, and does not follow the laws of physics. Descartes argued that only humans have minds, and that the mind interacts with the body at the pineal gland. This form of dualism proposes that the mind controls the body, but that the body can also influence the otherwise rational mind, such as when people act out of passion. Most of the previous accounts of the relationship between mind and body had been uni-directional.

Descartes suggested that the pineal gland is "the seat of the soul" for several reasons. First, the soul is unitary, and unlike many areas of the brain the pineal gland appears to be unitary (microscopic inspection reveals it is formed of two hemispheres). Second, Descartes observed that the pineal gland was located near the ventricles. He believed the animal spirits of the ventricles acted through the nerves to control the body, and that the pineal gland influenced this process. Finally, Descartes incorrectly believed that only humans have pineal glands, just as, in his view, only humans have minds. This led him to the belief that animals cannot feel pain, and Descartes's practice of vivisection (the dissection of live animals) became widely practiced throughout Europe until the Enlightenment.

Cartesian dualism set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the mind-body problem for many years after Descartes's death. The question of how a nonmaterial mind can influence a material body, without invoking supernatural explanations, remains an enigma to this day.

Modern scientists have criticized Cartesian dualism, as well as its influence on subsequent philosophers.

Mathematical legacy

Descartes' theory provided the basis for the calculus of Newton and Leibniz, by applying infinitesimal calculus to the tangent line problem, thus permitting the evolution of that branch of modern mathematics.[5] This appears even more astounding considering that the work was just intended as an example to his Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la verité dans les sciences (Discourse on the Method to Rightly Conduct the Reason and Search for the Truth in Sciences, better known under the shortened title Discours de la méthode).

Descartes' rule of signs is also a commonly used method in modern mathematics to determine possible quantities of positive and negative zeros of a function.

Descartes invented analytic geometry, and discovered the law of conservation of momentum. He outlined his views on the universe in his Principles of Philosophy.

Descartes also made contributions to the field of optics. He showed by using geometric construction and the law of refraction (also known as Descartes's law) that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42 degrees (that is, the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the ray passing from the sun through the rainbow's center is 42 ¬į).[6] He also independently discovered the law of reflection, and his essay on optics was the first published mention of this law.[7]

One of Descartes' most enduring legacies was his development of Cartesian geometry, the algebraic system taught in schools today. He also created exponential notation, indicated by numbers written in what is now referred to as superscript (such as x²).

Bibliography

Collected works

- 1983. Oeuvres de Descartes in 11 vols. Adam, Charles, and Tannery, Paul, eds. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin.

Collected English translations

- 1988. The Philosophical Writings Of Descartes in 3 vols. Cottingham, J., Stoothoff, R., Kenny, A., and Murdoch, D., trans. Cambridge University Press; vol 1, 1985, ISBN 978-0521288071; vol. 2, 1985, ISBN 978-0521288088; vol. 3, 1991, ISBN 978-0521423502)

- 1988, Descartes Selected Philosophical Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0521358124 ISBN 9780521358125 ISBN 0521352649 ISBN 9780521352642.

Single works

- 1618. Compendium Musicae.

- 1628. Rules for the Direction of the Mind.

- 1630‚Äď1633. Le Monde (The World) and L'Homme (Man). Descartes's first systematic presentation of his natural philosophy. Man was first published in Latin translation in 1662; The World in 1664.

- 1637. Discourse on the Method ("Discours de la Methode"). An introduction to Dioptrique, Des Météores and La Géométrie. Original in French, because intended for a wider public.

- 1637. La Géométrie. Smith, David E., and Lantham, M. L., trans., 1954. The Geometry of René Descartes. Dover.

- 1641. Meditations on First Philosophy. Cottingham, J., trans., 1996. Cambridge University Press. Latin original. Alternative English title: Metaphysical Meditations. Includes six Objections and Replies. A second edition published the following year, includes an additional ‚Äė‚ÄôObjection and Reply‚Äô‚Äô and a Letter to Dinet. HTML Online Latin-French-English Edition

- 1644. Les Principes de la philosophie. Miller, V. R. and R. P., trans., 1983. Principles of Philosophy. Reidel.

- 1647. Comments on a Certain Broadsheet.

- 1647. The Description of the Human Body.

- 1648. Conversation with Burman.

- 1649. Passions of the Soul. Voss, S. H., trans., 1989. Indianapolis: Hackett. Dedicated to Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia.

- 1657. Correspondence. Published by Descartes's literary executor Claude Clerselier. The third edition, in 1667, was the most complete; Clerselier omitted, however, much of the material pertaining to mathematics.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Encyclopedia Britannica, Ren√© Descartes. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Oregon State University Rene Descartes. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Rebecca Copenhaver, Forms of skeptisism. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ The British Journal of Psychiatry, books: Chosen by Raj Persaud. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Jan Gullberg, Mathematics From The Birth Of Numbers (W. W. Norton, 1997, ISBN 0-393-04002-X).

- ‚ÜĎ P.A. Tipler and G. Mosca, Physics For Scientists And Engineers (W. H. Freeman, 2004, ISBN 0-7167-4389-2).

- ‚ÜĎ Encarta, Ren√© Descartes. Retreieved August 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boyer, Carl. 1985. A History of Mathematics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02391-3.

- Clarke, Desmond. 2006. Descartes: A Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82301-3.

- Costabel, Pierre. 1987. René Descartes - Exercices pour les éléments des solides. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-040099-X

- Cottingham, John. 1992. The Cambridge Companion to Descartes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36696-8.

- Farrell, John. 2006. ‚ÄúDemons of Descartes and Hobbes.‚ÄĚ In Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau. Cornell University Press.

- Garber, Daniel. 1992. Descartes's Metaphysical Physics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-28219-8.

- Garber, Daniel, and Michael Ayers. 1998. The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53721-5.

- Gaukroger, Stephen. 1995. Descartes: An Intellectual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-823994-7.

- Grayling, A.C. 2005. Descartes: The Life and times of a Genius. New York: Walker Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 0-8027-1501-X.

- Keeling, S. V. 1968. Descartes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Melchert, Norman. 2002. The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-19-517510-7.

- Sorrell, Tom. 1987. Descartes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-287636-8.

- Sch√§fer, Rainer. 2006. Zweifel und Sein‚ÄĒDer Ursprung des modernen Selbstbewusstseins in Descartes' cogito. Wuerzburg: Koenigshausen & Neumann. ISBN 3-8260-3202-0.

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings¬†|¬† Eastern philosophy ¬∑ Western philosophy¬†|¬† History of philosophy¬†(ancient¬†‚ÄĘ medieval¬†‚ÄĘ modern¬†‚ÄĘ contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Information · History · Human nature · Language · Law · Literature · Mathematics · Mind · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Science · Social science · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Language · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ethics |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.