Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War was a part of the national and social turmoil caused by World War I (1914–1918) in Europe. The war was fought in Finland from January 27 to May 15, 1918, between the forces of the Social Democrats led by the People's Deputation of Finland, commonly called the "Reds" (punaiset), and the forces of the non-socialist, conservative-led Senate, commonly called the "Whites" (valkoiset). The Reds were supported by Bolshevist Russia, while the Whites received military assistance from the German Empire.

Defeat in World War I and the February and October Revolutions in 1917 caused a total collapse of the Russian Empire, and the destruction in Russia resulted in a corresponding breakdown of Finnish society during 1917. The Social Democrats on the left and conservatives on the right competed for the leadership of the Finnish state, which shifted from the left to the right in 1917. Both groups collaborated with the corresponding political forces in Russia, deepening the split in the nation.[1]

As there were no generally accepted police and army forces to keep order in Finland after March 1917, the left and right began building security groups of their own, leading to the emergence of two independent armed military troops, the White and Red Guards. An atmosphere of political violence and fear grew among the Finns. Fighting broke out during January 1918 due to the acts of both the Reds and Whites in a spiral of military and political escalation. The Whites were victorious in the ensuing war. In the aftermath of the 1917–1918 crisis and the Civil War, Finland passed from Russian rule to the German sphere of influence. The conservative senate attempted to establish a Finnish monarchy ruled by a German king, but after the defeat of Germany in World War I, Finland emerged as an independent, democratic republic.[2]

The Civil War remains the most controversial and emotionally loaded event in the history of modern Finland, and there have even been disputes about what the conflict should be called.[3] Approximately 37,000 people died during the conflict, including casualties at the war fronts and deaths from political terror campaigns and high prison camp mortality rates. The turmoil destroyed the economy, split the political apparatus, and divided the Finnish nation for many years. The country was slowly reunited through the compromises of moderate political groups on the left and right.[4] In the years since achieving independence, Finland has emerged as a staunch defender of human rights, as a strong advocate of the peaceful resolution of disputes and as champion of ecological sustainability.

Background

The main factor behind the Finnish Civil War was World War I. The conflict caused a collapse of the Russian Empire, mainly in the February Revolution and the October Revolution during 1917. This led to a formation of a large power vacuum and struggle for power. Finland, as a part of the Russian Empire, was strongly affected by the turmoil and by the war between Germany and Russia. Both empires had political, economic, and military interests in Finland. An earlier crisis in the relations between Imperial Russia and the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland had occurred in 1899 as the central administration had strengthened in Saint Petersburg, and the tension and competition rose between the major European powers at that time. The Russian leaders, as part of an attempt to unite the large, heterogeneous empire, had adopted the program of the Russification of Finland, with the aim of reducing Finnish autonomy. The Finns called this policy "the first period of oppression 1899–1905." As a reaction, plans for disengagement from Russia or achieving sovereignty for Finland were drawn up for the first time.[5]

Before the first period of russification, Finland had enjoyed autonomy inside Russia. Compared to other parts of the Russian Empire, Finno-Russian relations had been exceptionally peaceful and stable. As this policy altered due to the changes in the Russian military doctrine, the Finns began to strongly oppose the imperial system. Several political groups with different opposition policies arose; the most radical one, the activist movement, led to covert collaboration with Imperial Germany during World War I.[6]

Major reasons for the rising tensions among the Finns was the autocratic rule of the Russian Tsar, and the undemocratic class system of the estates in the Grand Duchy, originating in the Swedish regime of the seventeenth century, which effectively divided the Finnish people into two groups, separated economically, socially and politically. The labor movement activity after 1899 not only opposed Russification but also sought to develop a domestic policy that tackled social problems and responded to the demand for democracy. Finland's population grew rapidly in the nineteenth century, and a class of industrial and agrarian workers and property-less peasants emerged. The Industrial Revolution and economic freedom had arrived in Finland later than in Western Europe (1840–1870), owing to the rule of the House of Romanov. This meant that some of the social problems associated with industrialization were diminished by learning from the experiences of countries such as England. The social conditions, the standard of living, and the self-confidence of the workers gradually improved between 1870–1914, and at the same time the political concepts of socialism, nationalism and liberalism took root. But as the standard of living rose among the common people, the rift between rich and poor deepened markedly.[7]

The Finnish labor movement, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century out of folk and Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland#History|religious movements and fennomania, had a "Finnish national, working class" character and was represented by the Social Democratic Party, established in 1899. The movement came to the fore without major confrontations when tensions during Russia's failed war against Japan led in 1905 to a general strike in Finland and revolutionary upheaval in the empire. In an attempt to quell the general unrest, the system of estates was abolished in parliamentary reform of 1906, which introduced universal suffrage. All adults including female citizens were given the right to vote increasing the number of voters from 126,000 to 1,273,000. This soon produced around 50-percent turnouts for the Social Democrats, although there were no evident improvements for their supporters. The Russian Tsar, Nicholas II, regained his authority after this crisis, reclaimed his role as the Grand Duke of Finland, and during the second period of Russification between 1908 and 1917 neutralized the functions and powers of the new parliament. The confrontations between the Finnish people's representatives of the largely uneducated common man and the Finns of the former estates accustomed to the meritocratic rule and attitudes diminished also the capability of the new parliament to solve major social and economical problems during the ten years before the collapse of the Finnish state.[8]

February Revolution (1917)

The more severe program of Russification, called "the second period of oppression 1908–1917" by the Finns, was halted on March 15, 1917 by the removal of the Russian Tsar Nicholas II. The immediate reason for the collapse of the Russian Empire was a domestic crisis precipitated by defeats against Germany and by war-weariness among the Russian people. The deeper causes of the revolution lay in the collision between the policies of the most conservative regime in Europe and the necessity for political and economic modernization brought about by industrialization. The Tsar's power was transferred to the Russian Duma and Provisional Government, which at this time had a right-wing majority.[9]

Autonomous status was returned to the Finns in March 1917, and the revolt in Russia handed the Finnish Parliament true political power for the first time. The left comprised mainly Social Democrats, covering a wide spectrum from moderate to revolutionary socialists; the right was even more diverse, ranging from liberals and moderate conservatives to radical rightist elements. The four main parties were the two old Fennoman parties, the conservative Finnish Party and the Young Finnish Party including both liberals and conservatives; the social reformist, centrist Agrarian League, which drew its support mainly from peasants with small or middle-sized farms; and the conservative Swedish People's Party, which sought to retain the rights of the Swedish-speaking minority.

The Finns faced a detrimental interaction of power struggle and breakdown of society during 1917. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Finnish people stood at the crossroads between the old regime of the estates and the evolution of a modern, democratic society. The direction and goal of this period of change now became a matter of intense political dispute, which eventually spilled over into armed conflict due to the weakness of the Finnish state. The Social Democrats aimed at retaining the political rights already achieved and establishing influence over the people. The conservatives were fearful of losing their long-held social and economic power.[10]

The Social Democratic Party had gained an absolute majority in the Parliament of Finland as a result of the general elections of 1916.[11] The new Senate was formed by Social Democrat and trade union leader Oskari Tokoi. His Senate cabinet comprised six representatives from the Social Democrats and six from non-socialist parties. In theory, the new cabinet consisted of a broad coalition; in practice, with the main political groups unwilling to compromise and the most experienced politicians remaining outside it, the cabinet proved unable to solve any major local Finnish problems. Real political power shifted instead to street level in the form of mass meetings, protests, strike organizations, and the street councils formed by workers and soldiers after the revolution, all of which served to undermine the authority of the state.[12]

The rapid economic growth stimulated by World War I, which had raised the incomes of industrial workers during 1915 and 1916, collapsed with the February Revolution, and the consequent decrease in production and economy led to unemployment and heavy inflation. Large-scale strikes in both industry and agriculture spread throughout Finland, the workers calling for higher wages and eight-hour-per-day working limits. The cessation of cereal imports from Russia had produced food shortages in the country, as a response to which the government introduced rationing and price fixing. However, a black market formed in which food prices continued to rise sharply, which was a major problem for the unemployed worker families. Food supply, prices, and the fear of starvation became emotional political issues between farmers in the countryside and industrial workers in the urban areas. The common people, their fears exploited by the politicians and the political media, took to the streets. Despite the food shortages, no large-scale starvation hit the Finns in southern Finland before the war. Economic factors remained a supporting factor in the crisis of 1917, but only a secondary part of the power struggle of the state.[13]

Battle for leadership

The power struggle between the Social Democrats and the conservatives culminated in July 1917 in the passing of the Senate bill that eventually became the "Power Act," which incorporated a plan by the Social Democrats to substantially increase the power of Parliament, in which they had a majority; it also furthered Finnish independence by restricting Russia's influence on domestic Finnish affairs. The Social Democrats' plan had the backing of Vladimir Lenin and the Russian Bolsheviks, who in July 1917 were plotting a revolt against the Russian Provisional Government. The Agrarian Union, some rightist activists, and other non-socialists eager for Finnish sovereignty supported the act, but both the Finnish conservatives and the Russian Provisional Government opposed the measure because it would reduce their power. In the event, Lenin was thwarted during the "July Days" and forced to flee to Finland. The Provisional Russian Government refused to accept the Power Act and sent troops to Finland, where, with the support of the conservatives, Parliament was dissolved and new elections announced. In those elections, in October 1917, the Social Democrats lost their absolute majority, after which the labor movement's role changed. Until then, it had mainly struggled for new rights and benefits for its members; now the movement was forced to defend the gains it had already made.[14]

The collapse of Russia in the February Revolution resulted in a loss of institutional authority in Finland and the dissolution of the police force, creating fear and uncertainty. In response, groups on both the right and left began assembling independent security groups for their own protection. At first, these groups were local and largely unarmed, but by autumn 1917, in the power vacuum following the dissolution of parliament and in the absence of a stable government or a Finnish army, such forces began assuming a more military and national character.[15] The Civil Guards (later called the White Guards) were organized by local men of influence, usually conservative academics, industrialists and major landowners and activists, while the Worker's Security Guards (later called the Red Guards) were often recruited through their local party sections and the labor unions. The presence of these two opposing armed forces in the country imposed a state of “dual power" and "multiple sovereignty" on Finnish society, typically the prelude to civil war.[16]

October Revolution (1917)

Lenin's Bolshevik Revolution on November 7 transferred political power to the radical, left-wing socialists in Russia, a turn of events which suited a German Empire exhausted by fighting a war on two major fronts. The policy of the German leaders had been to foment unrest or revolution in Russia in order to force the Russians to sue for peace. To that end, they had arranged for the safe conduct of Lenin and his comrades from exile in Switzerland to Petrograd in April 1917. Furthermore, the Germans financed the Bolshevik party, believing Lenin to be the most powerful weapon they could launch at Russia.[17]

After the dissolution of the Finnish parliament, the polarization and mutual fear between the Social Democrats and the conservatives increased dramatically, a situation made worse when the latter, after their victory in the elections of October 1917, appointed a purely conservative cabinet. On November 1, the Social Democrats put forward a political program called “We demand” in order to push for political concessions in domestic policy. They planned also to ask for acceptance of Finland's sovereignty from the Bolsheviks in the form of a manifesto on November 10, but the uncertain situation in Petrograd stalled the plan. After the uncompromising "We demand" program had failed, the socialists initiated a general strike on November 14–19, 1917. At this moment, Lenin and the Bolsheviks, under threat in Petrograd, urged the Social Democrats to seize power in Finland, but the majority of the latter were moderate and preferred parliamentary methods, prompting Lenin to label them “reluctant revolutionaries.” When the general strike appeared to be successful, the “Workers' Revolutionary Council” voted by a narrow majority to seize power on November 16 at 5:00 a.m. The supreme revolutionary “Executive Committee,” however, was unable to recruit enough members to carry out the plan and had to call the proposed revolution off at 7:00 p.m. the same day. The incident, "the shortest revolution," effectively split the Social Democrats in two, a majority supporting parliamentary means and a minority demanding revolution. The repercussions of the event had a lasting effect on the future of the movement, with several powerful leaders staking positions within the party.[18]

The Finnish Parliament, influenced by the general strike, supported the Social Democratic proposals for an eight-hour working day and universal suffrage in local elections on November 16, 1917. During the strike, however, radical elements of the Workers' Security Guards executed several political opponents in the main cities of southern Finland, and the first armed clashes between Civil Guards and Workers' Guards broke out, with 34 reported casualties. The Finnish Civil War would probably have started at that point had there been enough weapons in the country to arm the two sides; instead, there began a race for weapons and a final escalation towards war.[19]

Finnish sovereignty

The disintegration of Russia offered the Finns a historic opportunity to gain independence, but after the October Revolution, the positions of the conservatives and the Social Democrats on the sovereignty issue had become reversed. The right was now eager for independence because sovereignty would assist them in controlling the left and in minimizing the influence of revolutionary Russia. The Social Democrats had supported independence since spring 1917, but now they could not use it for the direct political benefit of their party and had to adjust to the right's dominance in the country. Nationalism had become a "civic religion" among the Finns by the end of the nineteenth century, and during 1917 sovereignty was one of the few political questions on which most of the Finnish people agreed.[20]

The Senate, led by Pehr Evind Svinhufvud, proposed Finland's declaration of independence, which the Parliament adopted on December 6, 1917.[21] Though the Social Democrats voted against the Svinhufvud proposal, they decided to present an alternative declaration of independence containing no substantial differences. The socialists feared a further loss of support (as in the October elections) among the nationalistic common people and hoped to win a political majority in the future. They sent two delegations during December 1917 to Petrograd in order to appeal from Lenin an approval of Finnish independence. Both political groups, therefore, agreed on the need for Finnish sovereignty, despite strong disagreement on the selection of its leadership.[22]

The establishment of sovereignty was not a foregone conclusion; for a small nation like Finland, recognition by Russia and the major European powers was essential. Three weeks after the declaration of independence, Svinhufvud's cabinet concluded that it would have to negotiate with Lenin for Russian recognition. During December 1917, the Bolsheviks were under pressure in peace negotiations with Germany at Brest-Litovsk. Russia Bolshevism was in a deep crisis with a demoralized army and the fate of the October Revolution in doubt. Lenin calculated that the Bolsheviks could perhaps hold central parts of Russia but would have to give up some territories on its periphery, including Finland in the less important northwestern corner. As a result, Svinhufvud and his senate delegation won Lenin's concession of sovereignty on December 31, 1917.[23]

Warfare

Escalation

In hindsight the events of 1917 have been often seen simply as precursors of the Civil War, an escalation of the conflict starting with the February Revolution. But the opposing political factions made many failed attempts of their own to create a new order and prevent social breakdown in 1917.[24] The events of the general strike in November deepened the suspicion and mistrust in Finland and finally put the possibility of compromise out of reach. The conservatives and rightist activists saw the groups of radical workers active during the strike as a threat to the security of the former estates and the political right, so they resolved to use all means necessary to defend themselves, including armed force. At the same time, revolutionary workers and left-wing socialists were now considering removing the conservative regime by force rather than allowing the achievements of the workers' movement to be reversed. The result of this hardening of positions was that in late 1917, moderate, peaceful men and women, as so often throughout history, were forced to stand aside while the men with rifles stepped forward to take charge.[25]

The final escalation towards war began in early January 1918. The most radical Workers' Security Guards from Helsinki, Kotka and Turku changed their names to Red Guards and convinced those leaders of the Social Democrats who wavered between peace and war to support revolution. The Workers' Guards were officially renamed the Red Guards at the end of the same month, under the command of Ali Aaltonen, a former Russian army officer, who had been appointed in December. At the same time, the Svinhufvud Senate and the Parliament decided on January 12, 1918 to create a strong police authority, an initiative which the Workers' Security Guards saw as a step towards legalizing the White Guards. When the Senate renamed the White Guards the Finnish White Army, the Red Guards refused to recognize the title. On January 15, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, like Aaltonen a former officer in the Russian army, was appointed supreme commander of the White Guards. He located his headquarters in Vaasa, while Aaltonen located his in Helsinki.[26]

The official starting date of the Finnish Civil War is a matter for debate. The first serious battles were fought during January 17–20 in Karelia, in the south-eastern corner of Finland, mainly for control of the town of Viipuri and to win the race for weapons. The White Order to engage was issued on January 25; the Red Order of Revolution was issued on January 26. The next day, the White Guards attacked trains carrying a large shipment of weapons from Russia, as promised to the Reds by Lenin. The large scale mobilization of the Red Guards began in the late evening of January 27, followed by the corresponding act of the White Guards, with disarmament of Russian garrisons in Ostrobothnia during the early hours of January 28. A symbolic date for the start of the war could be January 26, when a group of Reds climbed the tower of Helsinki Workers' Hall and lit a red lantern to mark the start of the second major rebellion in the history of Finland.[27]

Brothers in arms

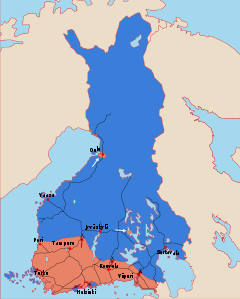

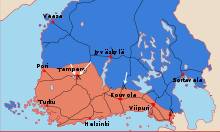

At the beginning of the war, the front line ran through southern Finland from west to east, dividing the country into White Finland and Red Finland. The Red Guards controlled the area to the south, including nearly all the major industrial centers and the largest estates and farms with high numbers of crofters and tenant farmers; the White Army controlled the area to the north, which was predominantly agrarian with small or medium-sized farms and tenant farmers, and where crofters were few or held a better social position than in the south. Enclaves of the opposing forces existed on both sides of the front line: within the White area lay the industrial towns of Varkaus, Kuopio, Oulu, Raahe, Kemi and Tornio; within the Red area lay Porvoo, Kirkkonummi and Uusikaupunki. The elimination of these strongholds was a priority for both armies during February 1918.

Red Finland, later named the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic, was led by the People's Council in Helsinki. Kullervo Manner was the chairman and other members included Otto Ville Kuusinen and Yrjö Sirola.[28] Bolshevist Russia declared its support for Red Finland, but the Reds' vision of democratic socialism for the country did not resemble Lenin's dictatorship of the proletariat,[29] and in fact, Lenin and his comrades wanted to annex Finland. The majority of Social Democrats intended to remain independent;[30] during the war, however, the Red Guards dominated the politics of Red Finland with their weapons, and the most radical Guards and the Finnish Bolsheviks, though few in number, obviously favored annexation of Finland back to Russia.[31] The Finnish senate (the Vaasa Senate) relocated to the west-coast city of Vaasa, which acted as the capital of White Finland from January 29 to May 3, and looked to Germany for military and political aid. Mannerheim agreed on the need for German weapons but opposed any intervention by German troops in Finland. The conservatives planned a monarchist political system, with a lesser role for Parliament. A section of the conservatives had always been against democracy; others had approved parliamentarianism at first but after the crisis of 1917 and the outbreak of war had concluded that empowering the common people would not work. Moderate non-socialists opposed any restriction of parliamentarianism and initially resisted German military help, but prolonged warfare changed their stance.[32] The Finnish Civil War was fought along the railways, the vital means of transporting troops and supplies.[33] The Red Guards' first objective was to cut the Whites' east-west rail connection, which they attempted north-east of Tampere, at the Battle of Vilppula. They also unsuccessfully tried to eliminate the Whites' bridgehead south of the River Vuoksi at Antrea on the Karelian Isthmus, a threat to their rail connection with Russia.

The number of troops on each side varied from 50,000 to 90,000. While the Red Guards consisted mostly of volunteers, the White Army contained only 11,000–15,000 volunteers, the remainder being conscripts. The main motives for volunteering were economic factors (salary, food), idealism, and peer pressure. The Red Guards also included 2,000 female troops, mostly young girls, recruited from the industrial centers of southern Finland. Both armies used juvenile soldiers, mainly between 15 and 17 years of age, the most famous example being Urho Kekkonen who fought for the White Army and later became the longest-serving President of Finland. Urban and agricultural workers constituted the majority of the Red Guards, whereas land-owning farmers and well-educated people formed the backbone of the White Army.[34]

Red Guards and the Russian Army

The Red Guards seized the early initiative in the war, taking control of Helsinki, the Finnish capital, in the early hours of January 28, and gaining first advantage with an "attack phase" that lasted till mid-March. However, a chronic shortage of skilled leaders, both at command level and in the field, left them unable to capitalize on their initial momentum, and most of the offensives finally came to nothing. The troops of the Red Guards were not professional soldiers but armed civilians, whose military training and discipline were mostly inadequate to resist the counter-attack of the White Army when it came, still less the onslaught of the German forces who arrived later. Consequently, Ali Aaltonen found himself rapidly replaced in command by Eero Haapalainen, who in turn was replaced by the triumvirate of Eino Rahja, Adolf Taimi and Evert Eloranta. The last commander of the Red Guards was Kullervo Manner, who led the final retreat into Russia. The only victories of the Finnish Red Guards were the heavy battles against German troops at Hauho and Tuulos, Syrjäntaka, on April 28–29 1918, during their retreat from southern Finland towards Russia, but these conflicts had only local importance by then.[35]

Although some 60,000 to 80,000 Russian soldiers of the former Tsar's army remained stationed in Finland at the start of the Civil War, the Russian contribution to the Red Guards' cause was to prove negligible. When the conflict began, Lenin tried to commit the Russian army on behalf of Red Finland, but the Russian troops were demoralized and war-weary after years of constant, traumatic defeat against Germany. The majority of the troops had returned to Russia by the end of March 1918. As a result, only 7,000 to 10,000 Russian soldiers participated in the Finnish Civil War, of which no more than 4,000, in separate small units, could be persuaded to fight in the front line. Despite the involvement of a few skilled Russian army officers such as Mikhail Svechnikov, who led the battles in western Finland throughout February 1918, it seems reasonable to assume that the Russian army had no significant influence on the course of the war.[36] The number of Russian soldiers active in the Civil War declined markedly once Germany attacked Russia on February 18, 1918, and delivered its terminal blow to the Russian army. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed between Russia and Germany on March 3, effectively restricted the Bolsheviks' ability to support the Finnish Red Guards with anything more than weapons and supplies.[37] The Russians did remain active on the south-eastern front, however, defending the approaches to Petrograd.

White Guards and the German Army

The military quality of the common soldier in the White Army differed little from that of his counterpart in the Red Guards, with brief and inadequate training provided for most of the troops.[38] But the White Army had two major advantages over the Red Guards: the professional military leadership of General Mannerheim and his staff—which included 84 Swedish volunteer officers as well as former Finnish officers of the Tsar's army—and approximately 1,300 "Jäger" (Jääkärit) elite Finnish troops, trained in Germany and battle-hardened on the Eastern Front.

Battle of Tampere

Mannerheim's strategy was to strike first at Tampere, Finland's most important industrial town in the southwest. He launched the attack on March 16 at Längelmäki, 65 kilometres northeast of Tampere; at the same time the White Army began advancing along a line through Vilppula–Kuru–Kyröskoski–Suodenniemi, north and northwest of Tampere. The Red Guards collapsed under the weight of the assault, and some of its detachments retreated in panic. The White Army cut off the Red Guards' retreat south of Tampere in Lempäälä and lay siege to Tampere on March 24, entering the town four days later. The true Battle of Tampere began on March 28, later called the "bloody Maundy Thursday" on the eve of Easter 1918. The battle for Tampere was fought between 16,000 White and 14,000 Red soldiers, and it was the decisive action of the war and the largest military engagement in Scandinavian history to that point. It was Finland's first urban battle, fought in the Kalevankangas graveyard and from house-to-house in the city as the Red Guards retreated. The battle, lasting until April 6, 1918, was the bloodiest action of the war; the motivation to fight for defense had increased markedly among the Reds, and the Whites had to use part of the fresh, best trained detachments of their army.[39] The fighting in Tampere was pure civil war, Finn against Finn, "brother rising against brother," since most of the Russian army had retreated to Russia in March and the German troops had yet to arrive in Finland. The White Army lost 700–900 men, including 50 Jägers. The Red Guards lost 1,000–1,500 soldiers, with a further 11,000-12,000 imprisoned. 71 civilians died mainly due to artillery fire. The eastern parts of the city, with wooden buildings, were destroyed completely.[40]

After their defeat in Tampere, the Red Guards retreated eastwards. The White Army shifted its military focus to Viipuri, Karelia's main city, taking it on April 29. The Red Guards' last strongholds in south-west Finland fell by May 5.[41]

German intervention

The German Empire finally intervened in the Finnish Civil War on the side of the White Army in March 1918. The activists had been seeking German aid in freeing Finland from Russian hegemony since Autumn 1917, but the Germans did not want to prejudice their armistice and |peace negotiations with Russia, the latter beginning on December 22 at Brest-Litovsk. The German stance altered radically after February 10 when Trotsky, despite the weakness of the Bolsheviks' position, broke off negotiations, hoping revolutions would break out in the German Empire and change everything. The German government promptly decided to teach Russia a lesson and, as a pretext for aggression, invited “requests for help” from the smaller countries west of Russia. Representatives of the Vaasa Senate in Berlin duly requested help on February 14.[42] The Germans attacked Russia on February 18.

On March 5 a German Naval squadron landed on the Åland Islands in the southwestern archipelago of Finland, where a Swedish military expedition had been protecting Swedish interests and the Swedish-speaking population since mid-February.[43] On April 3, 1918, the 10,000-strong Baltic Sea Division led by Rüdiger von der Goltz struck west of Helsinki at Hanko, and on April 7, the 3,000-strong Detachment Brandenstein overran the town of Loviisa on the southeastern coast. The main German formations then advanced rapidly eastwards from Hanko and took Helsinki on April 13. At the same time, two German battleships and smaller vessels entered the city harbor and bombarded the Red positions, which included the present-day Presidential Palace. The Brandenstein Brigade attacked the town of Lahti on April 19, cutting the connection between the western and eastern Red Guards. The main German detachment advanced northwards from Helsinki and took Hyvinkää and Riihimäki on April 21–22, followed by Hämeenlinna on April 26. The efficient performance of the German top detachments in the civil war contrasted strikingly with that of the demoralized Russian troops.[44]

Most members of the People's Deputation of Finland fled from Helsinki on April 8 and from Viipuri to Petrograd on April 25, with only Edvard Gylling remaining in Viipuri. The Finnish Civil War ended on May 14–15, when a small number of Russian troops retreated from a coastal artillery base on the Karelian Isthmus. White Finland celebrated its victory in Helsinki on May 16, 1918.[45]

Red and White terror

During the civil war, the White Army and the Red Guards both perpetrated acts of terror. According to earlier views, both sides had agreed to certain rules of engagement, but violations occurred from the start, most notably when Red Guards executed 17 troops at Suinula village on January 31, and when White Army soldiers executed 90 troops at Varkaus on February 21. After these incidents, both sides began carrying out revenge executions at local level, a trend which escalated to massacres and terrorism.[46]

Recent studies indicate, however, that the terror was a calculated part of the general warfare. The highest staffs of both sides planned these actions and gave orders to the lower level. At least a third of the Red terror and perhaps most of the White terror was centrally led. The governments of White Finland and Red Finland officially opposed acts of terror, but such operational decisions were made at the military level.[47]

Both armies deployed “flying detachments” of cavalry, usually consisting of 10 to 80 troops aged 15 to 20, under the absolute authority of an experienced adult leader. These units, which specialized in search-and-destroy operations behind the front lines and during and after battles, have been described as death squads.[48]

The Red Guards executed those they considered the main leaders of White Finland or as class enemies, including industrialists, politicians and major landowners. The two major sites of the Red terror were Toijala and Kouvola; there 300-350 Whites were executed between February and April 1918. The White Guards executed Red Guard and party leaders and those who participated in the war and Red terror. During the peak of the White terror, between the end of April and the beginning of May, 200 Reds were shot per day. The White terror hit particularly strongly the Russian soldiers who fought with the Red Guards.[49]

In total, 1,400–1,650 Whites were executed in the Red terror, and 7,000–10,000 Reds were executed in the White terror. The breakdown of the rules of engagement in the Finnish Civil War conformed to a pattern observed in many other civil wars.[50]

Aftermath

| Lives Lost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of death | Reds | Whites | Other | Total |

| Killed in action | 5,199 | 3,414 | 790 | 9,403 |

| Executed, shot or murdered | 7,370 | 1,424 | 926 | 9,720 |

| Prison camp deaths | 11,652 | 4 | 1,790 | 13,446 |

| Died after release from camp | 607 | - | 6 | 613 |

| Missing | 1,767 | 46 | 380 | 2,193 |

| Other causes | 443 | 291 | 531 | 1,265 |

| Total | 27,038 | 5,179 | 4,423 | 36,640 |

| Source: National Archive | ||||

Bitter legacy

The Civil War was a catastrophe for the Finnish nation. Almost 37,000 people perished, 5,900 of whom (16 percent of the total) were between 14 and 20 years old. A notable feature of the war was that only about 10,000 of these casualties occurred on the battlefields; most of the deaths resulted from the terror campaigns and from the appalling conditions in the prison camps. In addition, the war left about 20,000 children orphaned. A large number of Red Finland supporters fled to Russia at the end of the war and during the period that followed.[51]

The war created a legacy of bitterness, fear, hatred, and desire for revenge, and deepened the divisions within Finnish society. The conservatives and liberals disagreed strongly on the best system of government for Finland to adopt: the former demanded monarchy and restricted parliamentarianism; the latter demanded a Finnish republic with full-scale democracy and social reforms. A new conservative Senate, with a monarchist majority, was formed by J.K. Paasikivi.[52] All members of parliament who had taken part in the revolt were removed from office. This left only one social democrat later to be joined by two more.[53] A major consequence of the 1918 conflict was the breakup of the Finnish worker movement into three parts: moderate Social Democrats, left-wing socialists in Finland, and communists acting in Soviet Russia with the support of the Bolsheviks.[52]

In foreign policy, White Finland looked to Germany and its military might for support, and at the end of May the Senate asked the Germans to remain in the country. The agreements signed with Germany on March 7, 1918 in return for military support had bound Finland politically, economically, and militarily to the German Empire. The Germans proposed a further military pact in summer 1918 as a part of their plan to secure raw materials for German industry from Eastern Europe and tighten their control over Russia. General Mannerheim resigned his post on May 25 after disagreements with the Senate about German hegemony over the country and about his planned attack on Petrograd to repulse the Bolsheviks, which the Germans opposed under the peace treaty signed with Lenin at Brest-Litovsk. On October 9, under pressure from Germany, the monarchist Senate and the rump parliament chose a German prince, Friedrich Karl, brother-in-law of German Emperor William II, to be the King of Finland—and Finland approached the status of a monarchist state. All these measures diminished Finnish sovereignty. The Finns, both right and left, had achieved independence on December 6, 1917 without a gunshot but then compromised that independence by allowing the Germans to enter the country without difficulty during the civil war.[54]

The economic condition of the country had deteriorated so drastically that recovery to pre-conflict levels was not achieved until 1925. The most acute crisis was in the food supply, already deficient in 1917, though starvation had at that time been avoided in southern Finland. The Civil War, according to the leaders of Red Finland and White Finland, would solve all past problems; instead it led to starvation in southern Finland too. Late in 1918, Finnish politician Rudolf Holsti appealed for relief to Herbert Hoover, the chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium: Hoover arranged for food shipments and persuaded the Allies to relax their blockade of the Baltic Sea (which had obstructed food supplies to Finland) to allow the food in.[55]

Prison camps

The White Army and German troops captured about 80,000 Red prisoners by the end of the war on May 5, 1918. Once the White terror subsided, a few thousand including mainly small children and women, were set free, leaving 74,000-76,000 prisoners. The largest prison camps were Suomenlinna, an island facing Helsinki, Hämeenlinna, Lahti, Viipuri, Ekenäs, Riihimäki and Tampere. The Senate made the decision to keep these prisoners detained until each person's guilt could be examined. A law for a Tribunal of Treason was enacted on May 29 after a long dispute between the White army and the Senate of the proper trial method to adopt. The start of the heavy and slow process of trials was delayed further until June 18, 1918. The Tribunal did not meet all the standards of neutral justice, due to the mental atmosphere of White Finland after the war. Approximately 70,000 Reds were convicted, mainly for complicity to treason. Most of the sentences were lenient, however, and many got out on parole. Still 555 persons were sentenced to death, but only 113 were executed. The trials revealed also that some innocent persons had been imprisoned.[56]

Combined with the severe food shortage, the mass imprisonment led to high mortality rates in the camps, and the catastrophe was compounded by a mentality of punishment, anger and indifference on the part of the victors. Many prisoners felt that they were abandoned by their own leaders who had fled to Russia. The condition of the prisoners had weakened rapidly during May, after food supplies had been disrupted during the Red Guards' retreat in April, and a high number of prisoners had been captured already during the first half of April in Tampere and Helsinki. As a consequence, 2,900 starved to death or died in June as a result of diseases caused by malnutrition and Spanish flu, 5,000 in July, 2,200 in August, and 1,000 in September. The mortality rate was highest in the Ekenäs camp at 34 percent, while in the others the rate varied between 5 percent and 20 percent. In total, between 11,000 and 13,500 Finns perished. The dead were buried in mass graves near the camps.[57] The majority of the prisoners were paroled or pardoned by the end of 1918 after the change in the political situation. There were 6,100 Red prisoners left at the end of the year[58], 100 in 1921 (at the same time civil rights were given back to 40,000 prisoners) and in 1927 the last 50 prisoners were pardoned by the social democratic government led by Väinö Tanner. In 1973, the Finnish government paid reparations to 11,600 persons imprisoned in the camps after the civil war.[59]

Compromise

Just as the fate of the Finns was decided outside Finland in Petrograd on March 15, 1917, so it was decided outside Finland again on November 11, 1918, this time in Berlin, as Germany accepted defeat in World War I. The grand plans of the German Empire had finally come to nothing, and revolution had spread among the German people due to lack of food, war-weariness, and defeat in the battles on the Western Front. German troops left Helsinki on December 16, and Prince Friedrich Karl, who had not yet been crowned officially, left his post on December 20. Finland's status altered from a monarchist protectorate of the German Empire to an independent democratic republic on the model of the western democracies. The first local elections based on universal suffrage in the history of Finland were held during December 17–28, 1918, and the first parliamentary election after the Civil War on March 3, 1919. The United States and the United Kingdom recognized Finnish sovereignty on May 6–7, 1919.[60]

After the Civil War, in 1919 a moderate Social Democrat, Väinö Voionmaa, wrote: "Those who still trust in the future of this nation must have an exceptionally strong faith. This young independent country has lost almost everything due to the war...." At the same time, a liberal non-socialist, the eventual first president of Finland, K.J. Ståhlberg, elected July 25, 1919, wrote: "It is urgent to get the life and development in this country back on the path that we had already reached in 1906 and which the turmoil of war turned us away from." He was supported in that aim by Santeri Alkio, leader of the Agrarian Union and by moderate Finnish conservatives, such as Lauri Ingman.[61]

Together with other moderate politicians of the right and the left, the new partnership constructed a Finnish compromise which eventually delivered a stable and broad parliamentary democracy. This compromise was based both on the defeat of Red Finland in the Civil War and the fact that most of the political goals of White Finland had not been achieved. After the foreign forces left Finland, the Finns realized they had to get along with each other and that none of the main groups could be rejected completely from society. The reconciliation led to a slow and painful, but steady, national unification. The compromise has turned out to be surprisingly strong and appears permanent. From 1919 to 1991, Finnish democracy and sovereignty withstood challenges from both right-wing and left-wing radicalism, the crisis of World War II, and pressure from the Soviet Union during the Cold War.[62]

The Civil War in literature

The first generally appreciated book in Finland concerning the war, Hurskas kurjuus (Devout Misery), was written by the Nobel Prize winner Frans Emil Sillanpää in 1919. Between 1959 and 1962, Väinö Linna, in his trilogy Täällä Pohjantähden alla (Under the North Star), described the Civil War and the Second World War from the point of view of the common people. In poetry, Bertel Gripenberg, who had volunteered for the white army, celebrated its cause in Den stora tiden (The Great Age), 1928 (in Swedish). Viljo Kajava, who had experienced the horrors of the Battle of Tampere at the age of nine, presented a pacifist view of the civil war in his Poems of Tampere 1918 of the 1960s.

Notes

- ↑ Upton 1980, 109–114, 195–263; Alapuro 1988, 185–196; Haapala 1995, 11–13, 152–156.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 434–435; Ylikangas 1986, 163–172; Manninen 1992 in Manninen, ed., part I, 346–395, 398–433; Haapala. 1995, 223–225, 237–243; Vares. 1998, 56–137; Jussila. 2007, 264–291.

- ↑ The Finnish Civil War has also been called The Freedom War, The Brethren War, The Class War, The Red Rebellion, and The Finnish Revolution. Koskesta Voimaa, Haapala 1993 Retrieved February 18, 2009; Manninen 1993; Ylikangas 1993b; Lackman 2000.

- ↑ Haapala 1995, 241–256.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 13–15; Alapuro 1988, 110–114, 150–196; Haapala 1995, 11–13, 152–156; Jutikkala and Pirinen 2003, 397; Jussila 2007, 264–282.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 30–32; Lackman 2000.

- ↑ Haapala 1986; Apunen 1987, 73–133; Alapuro 1988; Haapala 1995, 62–66, 105–108.

- ↑ Apunen 1987, 242–250; Alapuro 1988, 85–100, 101–127, 150–151; Haapala 1995, 230–232; Vares 1998, 62–78; Jutikkala and Pirinen 2003, 372-373, 377; Jussila 2007, 244–263.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 51–54; Ylikangas 1986, 163–164; Jussila 2007, 230–243.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 109, 195–263; Alapuro 1988, 143–149; Haapala 1995, 11–14.

- ↑ Kirby. 2006, 150.

- ↑ Haapala 1995, 221, 232–235.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 95–98, 109–114; Ylikangas. 1986, 165–167; Alapuro. 1988, 163–164, 192; Haapala. 1995, 155, 197, 203–225.

- ↑ Enckell 1956; Upton 1980, 163–194; Alapuro 1988, 158–162, 195–196; Keränen. 1992, 50.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 195–230; Ylikangas 1986, 166–167; Haapala 1995, 237–243.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 195–230; Lappalainen 1981; Salkola 1985; Alapuro 1988, 151–167; Manninen 1993; Haapala 1995, 237–243.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 36; Lackman. 2000, 86-95.

- ↑ Ketola 1987, 368–384; Upton 1980, 264–342.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 317–342; Alapuro 1988, 167–171.

- ↑ Alapuro 1988, 89–100; Jussila. 2007, 9–10.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 73; Haapala 1995, 236.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 343–382; Alapuro. 1988, 189–192; Keränen 1992, 78; Manninen 1993; Jutikkala, in: Aunesluoma and Häikiö 1995, 11–20, Uta.fi/Suomi80.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 258–261; Keränen 1992, 79; Jussila. 2007, 183–197.

- ↑ Haapala 1995, 232.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 517–518; Alapuro. 1988, 185–196; Ylikangas 1993, 15–24; Haapala 1995, 221, 223–225; Jutikkala and Pirinen 2003, 389.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 390–500; Lappalainen 1981; Keränen 1992, 80–87.

- ↑ Upton 1980, 471–515; Lappalainen 1981.

- ↑ Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi 1999, 108.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 102.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 263–278; Manninen 1993.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 255–265; Manninen 1993.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 62–64; Vares 1998, 38–46, 56–79; Lackman 2000.

- ↑ Ylikangas 1993, 15–21.

- ↑ Lappalainen 1981; Manninen 1992–1993; Manninen in: Aunesluoma and Häikiö 1995, 21–32.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 227–255; Lappalainen 1981.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 265–276; Lappalainen 1981; Manninen in: Aunesluoma and Häikiö 1995, 21–32; Tikka. 2006.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 259–262; Manninen 1992–1993; Lackman 2000.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 62–144; Tikka 2006, 25–30.

- ↑ Ylikangas. 1993, 429–443.

- ↑ Ylikangas. 1993, 103–295; Aunesluoma and Häikiö. 1995, 92–97; Hoppu. 2007, 12–35.

- ↑ Lappalainen 1981; Upton 1981, 424–446; Aunesluoma and Häikiö 1995, 112; Lackman 2000.

- ↑ On March 7, representatives Hjelt and Erich agreed to pay the military costs of German military assistance. Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi. 1999, 117.

- ↑ The Swedish troops were forced to leave the area by May. Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi. 1999, 117.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 369–424; Arimo 1991; Manninen 1992–1993; Lackman 2000.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 137.

- ↑ Paavolainen 1966; Keränen 1992, 89, 101; Uola 1998; Tikka 2004, 232–240.

- ↑ Tikka 2004. 452–460; Tikka 2006, 69–138.

- ↑ Tikka 2006, 69–81, 141–146.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 121, 138; Tikka 2004. 96–108, 214–291.

- ↑ The Red casualties included 300-400 female soldiers, Paavolainen 1966 and 1967; Manninen 1992–1993; Eerola and Eerola 1998, 59, 91; Westerlund. 2004, 15.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 447–481; Haapala 1995, 9–13, 212–217; Peltonen 2003, 9–24, 214–220; Tikka 2004, 452–460.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Upton 1981, 447–453; Keränen 1992, 136; Manninen. 1992-1993; Vares 1998, 56–79.

- ↑ Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi. 1999, 121.

- ↑ Rautkallio 1977; Upton 1981, 480; Keränen 1992, 152; Manninen 1992–1993; Vares 1998, 199–249; Jussila 2007, 276–291.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 157; Haapala 1995, 9–13, 212–217.

- ↑ Paavolainen 1971; Kekkonen 1991; Keränen 1992, 140, 142; Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi 1999, 112; Tikka 2006, 161–178; Uta.fi/Suomi80/Yhteiskunta/Valtiorikosoikeudet.

- ↑ Paavolainen 1971; Manninen 1992–1993; Eerola and Eerola 1998, 114, 121, 123; Westerlund 2004, 115–150; Linnanmäki. 2005.

- ↑ Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi 1999. 112.

- ↑ Työväen Arkisto, (Finnish) Vuoden 1918 kronologia Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ Keränen 1992, 154, 171; Manninen 1992–1993.

- ↑ Ståhlberg, Ingman, Tokoi, and Miina Sillanpää with other moderate female politicians had desperately tried to avoid the war in Jan 1918 with a proposal for a new Senate including both non-socialist and socialist members, but they were run over. Haapala 1995. 243, 249; Vares 1998, 58, 96–99.

- ↑ Upton 1981, 480–481; Ylikangas 1986, 169–172; Haapala 1995, 243, 245–256.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alapuro, Risto. State and Revolution in Finland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988. ISBN 0520058135.

- Apunen, Osmo. "Rajamaasta tasavallaksi," 47-404 in Blomstedt, Y. ed. 1987. Suomen historia 6, Sortokaudet ja itsenäistyminen. Espoo, FI: Weilin + Göös, 1987. ISBN 978-9513524951.

- Arimo, Reino. Saksalaisten sotilaallinen toiminta Suomessa 1918. Rovaniemi, FI: Pohjois-Suomen historiallinen yhdistys, 1991. ISBN 9519617442.

- Aunesluoma, Juhana, and Martti Häikiö. Suomen vapaussota 1918. Kartasto ja tutkimusopas. Porvoo, FI: W. Söderström, 1995. ISBN 951020174X.

- Eerola, Jari, and Jouni Eerola. Henkilötappiot Suomen sisällissodassa 1918. Poroo, FI: W. Soderstrom, 1998. ISBN 9529100019.

- Enckell, Carl. Poliittiset muistelmani I. Porvoo, FI: WSOY.

- Gripenberg, Bertel. 1928. Den stora tiden. Stockholm: Björck & Borjesson, 1956.

- Haapala, Pertti. Tehtaan valossa. Teollistuminen ja työväestön muodostuminen Tampereella 1820–1920. Tampere, FI; Hki, FI: Osuuskunta Vastapaino : Suomen historiallinen seura, 1986. ISBN 9519254757.

- Haapala, Pertti. 1995. Kun yhteiskunta hajosi, Suomi 1914–1920. Helsinki, FI: Painatuskeskus. ISBN 978-9513715328.

- Hoppu, Tuomas. Casualties in the battle for Tampere in 1918. Journal of Finnish Military History 26 (2007):8-35.

- Jussila, Osmo, Seppo Hentilä, and Jukka Nevakivi. From Grand Duchy to a Modern State: A Political History of Finland since 1809. London, UK: C. Hurst & Co., 2000. ISBN 1850655286.

- Jussila, Osmo. Suomen historian suuret myytit. Helsinki, FI: W. Söderström, 2007. ISBN 978-9510331033.

- Jutikkala, Eino, and Kauko Pirinen. A History of Finland. Helsinki, FI: WSOY, 2003. ISBN 9510279110.

- Kajava, Viljo. Tampereen runot. Helsinki: Otava, 1966.

- Kekkonen, Jukka. Laillisuuden haaksirikko, rikosoikeudenkäyttö Suomessa vuonna 1918. Helsinki, FI: Lakimiesliiton Kustannus, 1991. ISBN 9516405479.

- Keränen, Jorma. Suomen itsenäistymisen kronikka. Jyväskylä, FI: Gummerus, 1992. ISBN 9512038005.

- Ketola, Eino. Kansalliseen kansanvaltaan. Suomen itsenäisyys, sosiaalidemokraatit ja Venäjän vallankumous 1917. Helsinki, FI: Tammi, 1987. ISBN 9513067289.

- Kirby, David. A Concise History of Finland. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 052183225X. Retrieved

July 26, 2022.

- Lackman, Matti. Suomen vai Saksan puolesta ? Jääkäreiden tuntematon historia. Helsingissä, FI: Otava, 2000. ISBN 951116158X.

- Lappalainen, Jussi T. Punakaartin sota, osat I-II. Helsinki, FI: Opetusministeriö, Punakaartin historiakomitea : Valtion painatuskeskus, 1981. ISBN 9518590710.

- Linnanmäki, Eila.Espanjantauti Suomessa. Influenssaepidemia 1918–1920. Helsinki, FI: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2005. ISBN 9517467168.

- Linna, Väinö, and Richard A. Impola. Under the North Star. Aspasia classics in Finnish literature. Beaverton, Ont., Canada: Aspasia Books, 2001. 978-0968905401

- Manninen, Ohto. Itsenäistymisen vuodet 1917–1920, osat I-III. Helsinki, FI: VAPK-kustannus, 1992–1993. ISBN 951370730X.

- Paavolainen, Jaakko. Poliittiset väkivaltaisuudet Suomessa 1918, 1 Punainen terrori. Helsinki, FI: Tammi, 1966.

- Paavolainen, Jaakko. Poliittiset väkivaltaisuudet Suomessa 1918, 2 Valkoinen terrori. Helsinki, FI: Tammi, 1967.

- Paavolainen, Jaakko. Vankileirit Suomessa 1918. Helsinki, FI: Tammi, 1971.

- Peltonen, Ulla-Maija. Muistin paikat. Vuoden 1918 sisällissodan muistamisesta ja unohtamisesta. Helsinki, FI: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2003. ISBN 9517464681.

- Rautkallio, Hannu. Kaupantekoa Suomen itsenäisyydellä. Helsinki, FI: Söderström, 1977. ISBN 9510084921.

- Salkola, Marja-Leena.Työväenkaartien synty ja kehitys 1917–1918 ennen kansalaissotaa. Helsinki, FI: Valtion painatuskeskus, 1985. ISBN 9518597391.

- Sillanpää, Frans Emil. Hurskas kurjuus (Devout Misery). Porvoossa: W. Söderström, 1919.

- Sillanpää, Frans Eemil. Hurskas kurjuus. Helsingissä: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava, 1988. ISBN 978-9511092797

- Tikka, Marko. Kenttäoikeudet. Välittömät ratkaisutoimet Suomen sisällissodassa 1918. Helsinki, FI: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2004. ISBN 951746651X.

- Tikka, Marko. Terrorin aika. Suomen levottomat vuodet 1917–1921. Jyväskylä, FI: Gummerus, 2006. ISBN 9512070510.

- Työväen Arkisto. (Finnish) Vuoden kronologia (1918). Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Uola, Mikko. 1998. Seinää vasten vain; poliittisen väkivallan motiivit Suomessa 1917–1918. Helsingissä, FI: Otava. ISBN 9511154400.

- Upton, Anthony F. Vallankumous Suomessa 1917–1918, osat I-II. Helsinki, FI: Kirjayhtymä, 1980–1981. ISBN 9512618281.

- Upton, Anthony F. The Finnish Revolution 1917–1918. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1980. ISBN 0816609055.

- Vares, Vesa. Kuninkaantekijät. Suomalainen monarkia 1917–1919, myytti ja todellisuus. Helsinki, FI: WSOY, 1998. ISBN 9510232289.

- Westerlud, Lars. Sotaoloissa vuosina 1914–1922 surmansa saaneet. Helsinki, FI: Valtioneuvoston kanslia, 2004. ISBN 9525354520.

- Ylikangas, Heikki. Käännekohdat Suomen historiassa. Porvoo, FI: Söderström, 1986. ISBN 9510137456.

- Ylikangas, Heikki. Tie Tampereelle. Helsinki, FI: WSOY, 1993. ISBN 9510188972.

External links

All links retrieved March 26, 2024.

- Vapaussota.fi – Foundation of Invalids of the War.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.