First War of Indian Independence

The First War of Indian Independence was a period of rebellions in northern and central India against British power in 1857–1858. The British usually refer to the rebellion of 1857 as the Indian Mutiny or the Sepoy Mutiny. It is widely acknowledged to be the first-ever united rebellion against colonial rule in India.[1]

Mangal Pandey, a Sepoy in the colonial British army, was the spearhead of this revolt, which started when Indian soldiers rebelled against their British officers over violation of their religious sensibilities. The uprising grew into a wider rebellion to which the Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah, the nominal ruler of India, lent his nominal support. Other main leaders were Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi and Tantia Tope. The British cruelly put down the uprising, slaughtering civilians indiscriminately.

The result of the uprising was a feeling among the British that they had conquered India and were entitled to rule. The Mughal Emperor was banished and Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom was declared sovereign. The British East India Company, which had represented the British Government in India and which acted as agent of the Mughals, was closed down and replaced by direct control from London through a Governor-General.

Prior to the revolt, some British officials in India saw Indians as equals and dreamed of a long-term partnership between Britain and India to the benefit of both. These officials had a sympathetic knowledge of Indian languages and culture. Afterwards, fewer officials saw value in anything Indian and many developed a sense of racial superiority, depicting India as a chaotic and dangerous place where the different communities, especially Muslim and Hindu, were only kept from butchering one another by Britain's exercise of power.

The rebellion was widely perceived to have been a mainly Muslim uprising, although prominent Hindus also participated. However, Muslims especially would find themselves less favored following this incident, with a few exceptions.[2] India's eventual partition into India and Pakistan, based on the "two nation" theory that her Hindus and Muslims represented two distinct nations whose people could not live together in peace, may be seen as another long-term result of the uprising.

In British memory, novels and films romanticize the event extolling the bravery of their soldiers, while in Indian memory rebels such as Rani Lakshmi Bai and Nana Sahib enjoy the status of a Joan of Arc or of a William Wallace, fighting injustice.

Causes of the Revolt

Prior to the revolt, it is strictly speaking inaccurate to speak of British rule in India. The legal status of the East India Company was as agent of the Mughul Emperor with taxation powers and trading privileges. De facto, however, within the Province of Bengal, they operated as the Government and indeed the senior British official was entitled "Governor-General." Through a series of treaties with surrounding Indian princes and rulers, the Company extended its power throughout huge tracts of Indian territory. One cause of the revolt was the Company's policy of annexing Princely states with which they enjoyed a treaty relationship when they decided that the ruler was corrupt, or because they did not recognize the heir to the throne (such as an adopted son, who could succeed under Hindu law but not British law). There was also a rumor that Britain intended to flood India with Christian missionaries, and that pork and beef grease was being used to oil the new Enfield rifle that had been issued to the Indian troops. The latter appears to have been what motivated both Hindu and Muslim Sepoys (that is, Indian soldiers of the Company) to revolt.

In the year 1857, the British Army inducted a new type of rifle, the Enfield, whose cartridge was said to be greased in cow and pig fat. Hindus consider the cow a sacred animal and refrain from eating beef, while Muslims consider it an offense to consume pork. The entire Indian faction of the British Army rose in rebellion against the British. Soon, the flames spread and it turned into a full-fledged rebellion.

The "Doctrine of Lapse"

Under the "Doctrine of Lapse" policy of Lord Dalhousie (Governor-General 1846-1856) many kingdoms like Jhansi, Awadh or Oudh, Satara, Nagpur and Sambalpur were annexed turning the heirs of these kingdoms into 'pensioners' overnight. Nobility, feudal landholders, and royal armies found themselves unemployed and humiliated. These people were ready to avenge the injustice at the hands of the British. In addition the Bengal army of the East India Company drew many recruits from Awadh. They could not remain unaffected by the discontent back home. The jewels of the royal family of Nagpur were publicly auctioned in Calcutta, a move that was seen as a sign of abject disrespect by the remnants of the Indian aristocracy.

Indians were unhappy with the heavy-handed rule of the Company which had embarked on a project of rather rapid expansion and Westernization. This included the outlawing of many religious customs, both Muslim and Hindu, which were viewed as uncivilized by the British. This included a ban on sati (widow burning)—though it should be noted that the Sikhs had long ago abolished sati and the Bengali reformer Ram Mohan Roy was campaigning against it. These laws caused outrage in some quarters, particularly amongst the population of Bengal. The British abolished child marriage, and claimed to have ended female infanticide, but this claim is doubtful without accompanying demographic data. The suppression of Thuggee was a less controversial reform, although the true nature of Thuggee (whether it was truly a widespread religious cult, or simply dacoity) is still disputed.

The justice system was considered inherently unfair to the Indians. In 1853, the British Prime Minister Lord Aberdeen opened the Indian Civil Service to native Indians; however, this was viewed by some of educated India as an insufficient reform. The official Blue Books—entitled "East India (Torture) 1855–1857"—that were laid before the British House of Commons during the sessions of 1856 and 1857, revealed that Company officers were allowed an extended series of appeals if convicted or accused of brutality or crimes against Indians. The Company also practiced financial extortion through heavy taxation. Failure to pay these taxes almost invariably resulted in appropriation of property.

The British policy of expansionism (the Doctrine of Lapse) was also greatly resented by the rulers who were displaced, and outraged many if not most of their subjects, particularly in Oudh. In eight years Lord Dalhousie, the then Governor-General of India, had annexed a quarter of a million square miles (650,000 km²) of land to the Company's territory.

Many of the Company's modernization efforts were viewed with automatic distrust; for example, it was feared that the railway, the first of which began running out of Bombay in the 1850s, was a demon.

However, some historians have suggested that the impact of these reforms has been greatly exaggerated, as the British did not have the resources to enforce them, meaning that away from Calcutta their effect was negligible. This was not the view taken by the British themselves after 1857: instead they scaled down their program of reform, increased the racial distance between Europeans and native Indians, and also sought to appease the gentry and princely families, especially Muslim, who had been major instigators of the 1857 revolt. After 1857, Zamindari (regional feudal officials) became more oppressive, the Caste System became more pronounced, and the communal divide between Hindus and Muslims became marked and visible, which some historians argue was due in great part to British efforts to keep Indian society divided. This tactic has become known as "divide and rule."

Start of the revolt

Several months of increasing tension and inflammatory incidents preceded the actual rebellion. Fires, possibly the result of arson, broke out near Calcutta on January 24, 1857. On February 26, 1857, the 19th Bengal Native Infantry (BNI) regiment came to know about new cartridges and refused to use them. Their Colonel confronted them angrily with artillery and cavalry on the parade ground, but then accepted their demand to withdraw the artillery, and cancel the next morning's parade.[3]

Mangal Pandey

On March 29, 1857 at the Barrackpore (now Barrackpur) parade ground, near Calcutta, Mangal Pandey of the 34th BNI attacked and injured the adjutant Lt. Baugh with a sword after shooting at him, but instead hitting his horse.

General John Hearsey came out to see him on the parade ground, and claimed later that Mangal Pandey was in some kind of "religious frenzy." He ordered a Jemadar Ishwari Prasad to arrest Mangal Pandey, but the jemadar refused. The whole regiment with the single exception of a soldier called Shaikh Paltu drew back from restraining or arresting Mangal Pandey.

Mangal Pandey, after failing to incite his comrades into an open and active rebellion, tried to take his own life by placing his musket to his chest, and pulling the trigger with his toe. He only managed to wound himself, and was court-martialed on April 6. He was hanged on April 8.

The Jemadar Ishwari Prasad too was sentenced to death and hanged on April 22. The whole regiment was disbanded - stripped of their uniforms because it was felt that they harbored ill-feelings towards their superiors, particularly after this incident. Shaikh Paltu was, however, promoted to the rank of Jemadar in the Bengal Army.

Sepoys in other regiments thought this a very harsh punishment. The show of disgrace while disbanding contributed to the extent of the rebellion in view of some historians, as disgruntled ex-sepoys returned home back to Awadh with a desire to inflict revenge, as and when the opportunity arose.

April saw fires at Agra, Allahabad and Ambala.

3rd Light Cavalry at Meerut

On May 9, 85 troopers of the 3rd Light Cavalry at Meerut refused to use their cartridges. They were imprisoned, sentenced to ten years of hard labor, and stripped of their uniforms in public. It has been said that the town prostitutes made fun of the manhood of the sepoys during the night and this is what goaded them. This claim is however not substantiated by historical accounts. Malleson records that the troops were constantly berated by their imprisoned comrades while processing on a long and humiliating march to the jail. It was this insult by their own comrades which provoked the mutiny. The sepoys knew it was very likely that they would also be asked to use the new cartridges and they too would have to refuse in order to save their caste, religion and social status. Since their comrades had acted only in deference to their religious beliefs the punishment meted out by the British colonial rulers was perceived as unjust by many.

When the 11th and 20th native cavalry of the Bengal Army assembled in Meerut on May 10, they broke rank and turned on their commanding officers. They then liberated the 3rd Regiment and attacked the European cantonment where they are reported to have killed all the Europeans they could find, including women and children, and burned their houses. There are however some contemporary British accounts that suggest that some sepoys escorted their officers to safety and then rejoined their mutinous comrades. In Malleson's words: "It is due to some of them [sepoys] to state that they did not quit Meerut before they had seen to a place of safety those officers whom they most respected. This remark applies specially to the men of the 11th N.I., who had gone most reluctantly into the movement. Before they left, two sipáhís of that regiment had escorted two ladies with their children to the carabineer barracks. They had then rejoined their comrades".[4] Some officers and their families escaped to Rampur, where they found refuge with the Nawab. Despite this, at the time wild rumours circulated about the complete massacre of all Europeans and native Christians at Meerut, the first of many such stories which would lead British forces to extremely violent reprisals against innocent civilians and mutinous sepoys alike during the later suppression of the revolt.

The rebellious forces were then engaged by the remaining British forces in Meerut. Meerut had the largest percentage of British troops of any station in India: 2,038 European troops with 12 field guns versus 2,357 sepoys lacking artillery. Some commentators believe that the British forces could have stopped the sepoys from marching on Delhi, but the British commanders of the Meerut garrison were extraordinarily slow in reacting to the crisis. They did not even send immediate word to other British cantonments that a rebellion was in process. It seems likely that they believed they would be able to contain the Indians by themselves. This misjudgment would cost them dearly.

Support and Opposition

The rebellion now spread beyond the armed forces, but it did not result in a complete popular uprising as its leaders hoped. The Indian side was not completely unified. While Bahadur Shah Zafar was restored to the imperial throne there was a faction that wanted the Maratha rulers to be enthroned as well, and the Awadhis wanted to retain the powers that their Nawab used to have.

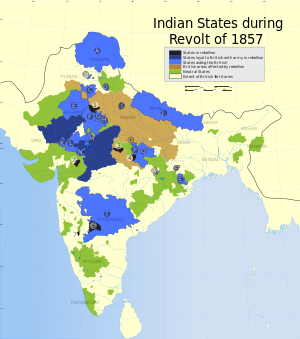

The war was mainly centered in northern and central areas of India. Delhi, Lucknow, Cawnpore, Jhansi, Bareilly, Arrah and Jagdishpur were the main centers of conflict. The Bhojpurias of Arrah and Jagdishpur supported the Marathas. The Marathas, Rohillas and the Awadhis supported Bahadur Shah Zafar and were against the British.

There were calls for jihad by some leaders including the millenarian Ahmedullah Shah, taken up by the Muslims, particularly Muslim artisans, which caused the British to think that the Muslims were the main force behind this event. In Awadh, Sunni Muslims did not want to see a return to Shiite rule, so they often refused to join what they perceived to be a Shia rebellion. Sir William Muir, the civil servant and scholar who later became Lt. Governor of the North West Provinces was head of intelligence during the rebellion, and recorded many details of the conflict in his Records of the NWP Intelligence Department (1902). From Agra, where he and his fellow British took refuge in the Red Fort, he wrote:

The Muslims defied our government in the most insolent manner. All the ancient feelings of warring for the faith reminding one of the first caliphs were resurrected. Few of the families who were otherwise strongly loyal to us could resist the temptation.[5]

In Thana Bhawan, the Sunnis declared Haji Imdadullah their Ameer. In May 1857 the famous Battle of Shamli took place between the forces of Haji Imdadullah and the British.

Many Indians supported the British, partly due to their dislike at the idea of return of Mughal rule and partly because of the lack of a notion of Indianness. The Sikhs and Pathans of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province supported the British and helped in the capture of Delhi. The Sikhs wanted to avenge the annexation of Punjab 8 years ago by the British with the help of Purbhais (Bengali's and Marathi's - Easterner) who helped the British. The Gurkhas of Nepal continued to support the British as well, although Nepal remained an independent country throughout the rebellion. Most of southern India remained passive with only sporadic and haphazard outbreaks of violence. Most of the states did not take part in the war as many parts of the region were ruled by the Nizams or the Mysore royalty and were thus not directly under British rule. The Westernized intellectuals felt that English rule would modernize and democratize the country and supported the foreigners.

Initial stages

Bahadur Shah Zafar proclaimed himself the Emperor of the whole of India. Most contemporary and modern accounts however suggest that he was coerced by the sepoys and his courtiers - against his own will - to sign the proclamation. The civilians, nobility and other dignitaries took the oath of allegiance to the Emperor. The Emperor issued coins in his name, one of the oldest ways of asserting Imperial status, and his name was added to the Khutbah, the acceptance by Muslims that he is their King.

Initially, the Indian soldiers were able to significantly push back Company forces. The sepoys captured several important towns in Haryana, Bihar, Central Provinces and the United Provinces. The British forces at Meerut and Ambala held out resolutely and withstood the sepoy attacks for several months.

The British proved to be formidable foes, largely due to their superior weapons, training, and strategy. The sepoys who mutinied were especially handicapped by their lack of a centralized command and control system.

Delhi

The British were slow to strike back at first but eventually two columns left Meerut and Simla. They proceeded slowly towards Delhi and fought, killed, and hanged numerous Indians along the way. At the same time, the British moved regiments from the Crimean War, and diverted European regiments headed for China to India.

After a march lasting two months, the British fought the main army of the rebels near Delhi in Badl-ke-Serai and drove them back to Delhi. The British established a base on the Delhi ridge to the north of the city and the siege began. The siege of Delhi lasted roughly from the 1st of July to the 31st of August. However, the encirclement was hardly complete—the rebels could easily receive resources and reinforcements. Later the British were joined by the Punjab Movable Column of Sikh and Pathan soldiers under John Nicholson and elements of the Gurkha Brigade.

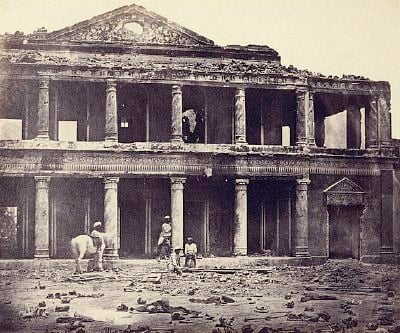

Eagerly-awaited heavy siege guns did not guarantee an easy victory against the numerical superiority of the sepoys. Eventually the British broke through the Kashmiri gate and began a week of street fighting. When the British reached the Red Fort, Bahadur Shah had already fled to Humayun's tomb. The British had retaken the city.

The troops of the besieging force proceeded to loot and pillage the city. A large number of the citizens were slaughtered in retaliation for the Europeans and Indian 'collaborators' that had been killed by the rebel sepoys. Artillery was set up in the main mosque in the city and the neighborhoods within the range of artillery were bombarded. These included the homes of the Muslim nobility from all over India, and contained innumerable cultural, artistic, literary and monetary riches. An example would be the loss of most of the works of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, thought of as the greatest Indian poet of that era.

The British soon arrested Bahadur Shah, and the next day British officer William Hodson shot his sons Mirza Mughal, Mirza Khizr Sultan, and Mirza Abu Bakr under his own authority at the Khooni Darwaza (the bloody gate) near Delhi Gate. Their heads were reportedly presented to their father the next day.

Cawnpore (Kanpur)

In June, sepoys under General Wheeler in Kanpur, (known as Cawnpore by the British) rebelled and besieged the European entrenchment. The British lasted three weeks of the Siege of Cawnpore with little water or food, suffering continuous casualties to men, women and children. On June 25 the Nana Sahib told British troops to surrender and Wheeler had little choice but to accept. The Nana Sahib promised them safe passage to a secure location but when the British boarded riverboats, firing broke out. Who fired first has remained a matter of debate.

During the march to the boats, loyal sepoys were removed by the mutineers and lynched along with any British officer or soldier that attempted to help them, although these attacks were ignored in an attempt to reach the boats safely. After firing began the boat pilots fled, setting fire to the boats, and the rebellious sepoys opened fire on the British, soldiers and civilians. One boat with over a dozen wounded men initially escaped, however, this boat later grounded, was caught by mutineers and pushed back down the river towards carnage at Cawnpore. The female occupants were removed and taken away as hostages and the men, including the wounded and elderly, were hastily put against a wall and shot. Only four men eventually escaped alive from Cawnpore on one of the boats: two privates (both of whom died later during the mutiny), a Lieutenant, and Captain Mowbray Thomson, who wrote a firsthand account of his experiences entitled The Story of Cawnpore (London) 1859.

The surviving women and children of the firing were led to Bibi-Ghar (the House of the Ladies) in Cawnpore. On the 15th of July, after noticing the approach of the British forces and believing that they would not advance if there were no hostages to save, their murders were ordered. After the sepoys refused to carry out this order, four butchers from the local market went into the Bibi-Ghar where they proceeded to hack the hostages apart with cleavers and hatchets. The victims' bodies, some still living, were thrown down a well.

The killing of the women and children proved to be a mistake. The British public was aghast and the pro-Indian proponents lost all their support. Cawnpore became a war cry for the British and their allies for the rest of the conflict. The Nana Sahib disappeared and was never heard of again.

When the British retook Cawnpore later, the soldiers took their sepoy prisoners to the Bibi-Ghar and forced them to lick the bloodstains from the walls and floor. They then hanged or "blew from the cannon" the majority of the sepoy prisoners. Although some claimed the sepoys took no actual part in the killings themselves, they did not act to stop it and this was acknowledged by Captain Thompson after the British departed Cawnpore for a second time.

Lucknow

Rebellion erupted in the state of Awadh (also known as Oudh, in modern-day Uttar Pradesh) very soon after the events in Meerut. The British commander of Lucknow, Henry Lawrence, had enough time to fortify his position inside the Residency compound. British forces numbered some 1700 men, including loyal sepoys. The rebels initial assaults were unsuccessful, and so they began a barrage of artillery and musket fire into the compound. Lawrence was one of the first casualties. The rebels tried to breach the walls with explosives and bypass them via underground tunnels that led to underground close combat. After 90 days of siege, numbers of British were reduced to 300 loyal sepoys, 350 British soldiers and 550 non-combatants. This action quickly became known as the Siege of Lucknow.

On the September 25 a relief column under the command of Sir Henry Havelock and accompanied by Sir James Outram (who in theory was his superior) fought its way to Lucknow in a brief but well commanded campaign in which the numerically small column defeated mutineer forces in a series of increasingly large battles. This became known as 'The First Relief of Lucknow', as this force was not strong enough to break the siege or extricate themselves and so was forced to join the garrison. In October another, larger, army under the new Commander-in-Chief, Sir Colin Campbell, was finally able to relieve the garrison and on the 18th of November they evacuated the city, the compound women and children leaving first. They then conducted an orderly withdrawal to now-retaken Cawnpore.

Jhansi

Jhansi was a Maratha-ruled princely state in Bundelkhand. When the Raja of Jhansi died without a male heir in 1853, Jhansi was annexed to the British Raj by the Governor-General of India under the Doctrine of Lapse. His widow, Rani Lakshmi Bai, protested the annexation on the grounds that she had not been allowed to adopt a successor, as per Indian custom.

When the Rebellion broke out, Jhansi quickly became a centre of the rebellion. A small group of British officials and their families took refuge in Jhansi's fort, and the Rani negotiated their evacuation. When the British left the fort, they were massacred by the rebels. Although the massacre might have occurred without the Rani's consent, the British suspected her of complicity in the slaughter, despite her protestations of innocence.

In September and October 1857, the Rani led the successful defence of Jhansi from the invading armies of the neighboring rajas of Datia and Orchha. In March 1858, the Central India Field Force, led by Sir Hugh Rose, advanced on and laid siege to Jhansi. The British captured the city, but the Rani fled in disguise.

These events, with significant fictional embellishments, form the basis of John Masters' book, Nightrunners of Bengal.

Other areas

On June 1, 1858, Rani Lakshmi Bai and a group of Maratha rebels captured the fortress city of Gwalior from the Scindia rulers, who were British allies. The Rani was killed three weeks later at the start of the British assault, when she was hit by a spray of bullets after fleeing Gwalior. The British captured Gwalior three days later.

The Rohillas centered in Bareilly were also very active in the war and this area was amongst the last to be captured by the rebels.

Retaliation – "The Devil's Wind"

From the end of 1857, the British had begun to gain ground again. Lucknow was retaken in March 1858. On July 8, 1858, a peace treaty was signed and the war ended. The last rebels were defeated in Gwalior on June 20, 1858. By 1859, rebel leaders Bakht Khan and Nana Sahib had either been slain or had fled. The British adopted the old Mughal punishment for mutiny and sentenced rebels were lashed to the mouth of cannons and blown to pieces. It was a crude and brutal war, with both sides resorting to what would now be described as war crimes. In the end, however, in terms of sheer numbers, the casualties were significantly higher on the Indian side. A letter published after the fall of Delhi in the "Bombay Telegraph" and subsequently reproduced in the British press testified to the scale of the retaliation:

"…. All the city people found within the walls (of the city of Delhi) when our troops entered were bayoneted on the spot, and the number was considerable, as you may suppose, when I tell you that in some houses forty and fifty people were hiding. These were not mutineers but residents of the city, who trusted to our well-known mild rule for pardon. I am glad to say they were disappointed."

Another brief letter from General Montgomery to Captain Hodson, the conqueror of Delhi exposes how the British military high command approved of the cold blooded massacre of Delhites: "All honor to you for catching the king and slaying his sons. I hope you will bag many more!"

Another comment to the conduct of the British soldiers after the fall of Delhi is of Captain Hodson himself in his book, Twelve years in India: "With all my love for the army, I must confess, the conduct of professed Christians, on this occasion, was one of the most humiliating facts connected with the siege."

Edward Vibart, a 19-year-old officer, also recorded his experience: "It was literally murder…. I have seen many bloody and awful sights lately but such a one as I witnessed yesterday I pray I never see again. The women were all spared but their screams on seeing their husbands and sons butchered, were most painful…. Heaven knows I feel no pity, but when some old gray bearded man is brought and shot before your very eyes, hard must be that man's heart I think who can look on with indifference…."

As a result, the end of the war was followed by the execution of a vast majority of combatants from the Indian side as well as large numbers of civilians perceived to be sympathetic to the rebel cause. The British press and British government did not advocate clemency of any kind, though Governor General Canning tried to be sympathetic to native sensibilities, earning the scornful sobriquet " Clemency Canning." Soldiers took very few prisoners and often executed them later. Whole villages were wiped out for apparent pro-rebel sympathies. The Indians called this retaliation "the Devil's Wind."

Reorganization

The rebellion also saw the end of the British East India Company's rule in India. In August, by the Queen's Proclamation of 1858, power was transferred to the British Crown. A secretary of state was entrusted with the authority of Indian affairs and the Crown's viceroy in India was to be the chief executive. The British embarked on a program of reform, trying to integrate Indian higher castes and rulers into the government and abolishing the East India Company.

Militarily, the rebellion transformed both the 'native' and European armies of British India. The British also increased the number of British soldiers in relation to native ones. Regiments which had remained loyal to the British were retained, and Gurkha units, which had been crucial in the Delhi campaign, were increased. The inefficiencies of the old organization, which had estranged sepoys from their British officers, were addressed, and the post-1857 units were mainly organized on the 'irregular' system. Sepoy artillery was abolished also, leaving all artillery in British hands. The post-rebellion changes formed the basis of the military organization of British India until the early twentieth century.

The East India Company's European forces in the three presidency armies (of Bengal, Madras and Bombay) were transferred to the Queen's army. This move precipitated the 'white mutiny' of 1859. European troops, who had enlisted for the Company's army and hoped to secure a bounty for re-engagement with the British army or simply to go home, reacted strongly to the change. European troops in Bengal mounted the largest collective protest the British army has ever seen, forcing the Government of India to offer men their discharge, which over 10,000 accepted. The protest left European military force in India in the hands of the Queen's army.

The viceroy stopped land grabs, decreed religious tolerance and admitted Indians into civil service, albeit mainly as subordinates. Bahadur Shah was tried for treason by a military commission assembled at Delhi, and exiled to Rangoon where he died in 1862, finally bringing the Mughal dynasty to an end. In 1877 Queen Victoria took the title of Empress of India on the advice of her Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. An official report by Sir William W. Hunter (1840-1900) on whether Muslims could be expected to give loyal service to the Queen concluded that they could not be expected to do so but were bound by their faith to rebel. This impacted on how Muslims were treated in British India.

Debate over name of conflict

There is no agreed name for the events of this period, but terms in use include First War of Independence, War of Independence of 1857, Indian Mutiny (historically the usual term in British discourse), the Great Indian Mutiny, the Sepoy Mutiny, the Sepoy Rebellion, the Great Mutiny, the Rebellion of 1857 and the Revolt of 1857. William Dalrymple, in The Last Mughal (2007), refers to it as the Uprising.

Although many Indian historians do term it as mutiny as well, on the Indian subcontinent it is commonly referred to as a war of independence, and the use of the term Indian Mutiny is considered unacceptable and offensive by many, as it is perceived to belittle what they see as a First War of Independence and therefore reflecting a biased, imperialistic attitude of the erstwhile colonists.

For example, in October, 2006, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Indian Parliament said:

The War of 1857 was undoubtedly an epoch-making event in India’s struggle for freedom. For what the British sought to deride as a mere sepoy mutiny was India’s First War of Independence in a very true sense, when people from all walks of life, irrespective of their caste, creed, religion and language, rose against the British rule.

Not only did these martyrs give up their lives for the sake of the country’s freedom but also left a message for the future generations — a message of sacrifice, courage of conviction, a strong belief in the ultimate victory of the people in their war against oppression.

With these words, I once again pay my humble tributes to the martyrs of the 1857 War of Independence.[6]

Besides this, a contemporary British chronicler, Thomas Lowe, in Central India during the rebellion, wrote in 1860: "To live in India, now, was like standing on the verge of a volcanic crater, the sides of which were fast crumbling away from our feet, while the boiling lava was ready to erupt and consume us."[7] Further, Lowe exclaimed: “The infanticide Rajput, the bigoted Brahmin, the fanatic Mussalman, had joined together in the cause; cow-killer and the cow-worshiper, the pig-hater and the pig-eater ... had revolted together.”[8]

Debate over the national character of the rebellion

Historians remain divided on whether the rebellion can properly be considered a war of Indian independence or not, although it is popularly considered to be one in India. Arguments against include:

- A united India did not exist at that time in political terms;

- The rebellion remained confined to the ranks of the Bengal Army (which nonetheless was the largest of the armies in India) and in North-Central India;

- The mutiny was put down with the help of other Indian soldiers drawn from the Madras Army, the Bombay Army and the Sikh regiments;

- Many princes and maharajahs did not participate in the rebellion, and those that did were basically interested in reviving and reclaiming their own principalities and fiefdoms, not in creating a United India;

- The Army and the Princes, who were the principal instigators of the rebellion of 1857, played no part in the Nationalist movement as it emerged in the 1880s;

- The Westernized intellectuals supported the British; however, an exception to this rule was Azimullah Khan, a Westernized rebel supporter.

A second school of thought while acknowledging the validity of the above-mentioned arguments opines that this rebellion may indeed be called a war of India's independence. The reasons advanced are:

- Even though the rebellion had various causes (e.g., sepoy grievances, British high-handedness, the Doctrine of Lapse etc.), most of the rebel sepoys set out to revive the old Mughal Empire, that signified a national symbol for them, instead of heading home or joining services of their regional principalities, which would not have been unreasonable if their revolt were only inspired by grievances;

- There was a widespread popular revolt in many areas such as Awadh, Bundelkhand and Rohilkhand. The rebellion was therefore more than just a military mutiny, and it spanned more than one region;

- The sepoys did not seek to revive small kingdoms in their regions, instead they repeatedly proclaimed a "country-wide rule" of the Moghuls and vowed to drive out the British from "India," as they knew it then. (The sepoys ignored local princes and proclaimed in cities they took over: Khalq Khuda Ki, Mulk Badshah Ka, Hukm Subahdar Sipahi Bahadur Ka - i.e., the world belongs to God, the country to the Emperor and executive powers to the Sepoy Commandant in the city). The objective of driving out "foreigners" from not only one's own area but from their conception of the entirety of "India," signifies a nationalist sentiment;

- The troops of the Bengal Army were used extensively in warfare by the British and had therefore traveled extensively across the Indian subcontinent, leading them perhaps to develop some notion of a nation-state called India. They displayed for the first time in this mutiny, some contemporary British accounts (Malleson) suggest, patriotic sentiments in the modern sense.

In short, we may summarize the discussion in following terms.

- If the criterion of a National War of Independence is set as "a war (or numerous conflicts) spread all over the nation cutting across regional lines," the rebellion in that case does not qualify as a war of India's independence.

- If the criterion for a National War of Independence is set as "a war, which even if geographically confined to certain regions, is waged with the intention of driving out from the complete national area a power perceived to be foreign," then it was a war of national independence.

This discussion shows that the term "national war" is subject to individual opinions and cannot be answered decisively.

Notes

- ↑ The term 'mutiny' is somewhat appropriate, in that the revolt started when Indian soldiers rebelled against their British officers, but is inappropriate as a description of the wider rebellion in which many Indians who were not serving under the British participated, and to which the Mughal Emperor lent nominal leadership. Technically, the British exercised power as agents of the Mughal Emperor, thus sovereignty was still vested in the Emperor, who could not mutiny against himself.

- ↑ Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, for example, was rewarded for his loyal service reaching a high judicial rank.

- ↑ Memorandum from Lieutenant-Colonel W. St. L. Mitchell (CO of the 19th BNI) to Major A. H. Ross about his troop's refusal to accept the Enfield cartridges, February 27, 1857 Archives of Project South Asia, South Dakota State University and Missouri Southern State University. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ↑ Sir John Kaye & G.B. Malleson, The Indian Mutiny of 1857 (Praeger, 1971 (original 1890), ISBN 0837140927), 49.

- ↑ Clinton Bennett, In Search of Muhammad (Continuum, 1998, ISBN 978-0304337002).

- ↑ Address at the Function marking the 150th Anniversary of the Revolt of 1857 Office of the Speaker Lok Sabha, October 10, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ↑ Renu Saran, Freedom Struggle of 1857 (Diamond Pocket Books, 2015).

- ↑ Aijaz Ahmad, Uprising of 1857: Some Facts about Failure of Indian War of Independence (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015, ISBN 978-1508550723).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahmad, Aijaz. Uprising of 1857: Some Facts about Failure of Indian War of Independence. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015. ISBN 978-1508550723

- Barter, Captain Richard, and Christopher Hibbert. The Siege of Delhi. Mutiny memories of an old officer. London: The Folio Society, 1984. ASIN B000E4WWM6

- Bennett, Clinton. In Search of Muhammad. Continuum, 1998. ISBN 978-0304337002

- Dalrymple, William. The Last Mughal: the fall of a dynasty: Delhi, 1857. NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. ISBN 978-1400043101

- David, Saul. The Indian Mutiny: 1857. Gardners Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0141005546

- Fitchett, W.H. A Tale of the Great Mutiny. Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1911). ISBN 978-1330096208

- Hibbert, Christopher. The Great Mutiny: India 1857. Penguin Books, 1980. ISBN 978-0140047523

- Hunter, Sir William W. The Indian Musalmans: Are They Bound in Conscience to Rebel Against the Queen? Andesite Press, 2015 (original 1871). ISBN 978-1296519612

- Innes, Lt. General McLeod. The Sepoy Revolt. Palala Press, 2015. (original 1897). ISBN 978-1341102028

- Kaye, Sir John, and George Bruce Malleson, The Indian Mutiny of 1857. Praeger, 1971 (original 1890). ISBN 0837140927

- Roberts, Field Marshal Lord. Forty-one Years in India. Forgotten Books, 2017 (original 1897). ISBN 978-1528279895

- Roy, Tapti. The Politics of a Popular Uprising: Bundelkhand 1857. Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0195636120

- Saran, Renu. Freedom Struggle of 1857. Diamond Pocket Books, 2015.

- Stanley, Peter. White Mutiny: British Military Culture in India, 1825-1875. NY: New York University Press, 1998. ISBN 0814780830

- Taylor, P. J. O. What really happened during the mutiny: a day-by-day account of the major events of 1857 - 1859 in India. Delhi: for the Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0195641825

- Trevelyan, Sir George Otto. Cawnpore. Indus, Delhi, (first edition 1865) Boston, MA: Adamant Media Corporation, 2002. ISBN 1402181922

- Wilberforce, Reginald G. An Unrecorded Chapter of the Indian Mutiny, Being the Personal Reminiscences of Reginald G. Wilberforce, Late 52nd Infantry, Compiled from a Diary and Letters Written on the Spot. London: John Murray, 1884, facsimile reprint: Gurgaon: The Academic Press, 1976. ASIN B000LVNMGW

External links

All links retrieved March 28, 2024.

- Truth behind 1857 part I. The Panthic Weekly.

- Truth behind 1857 part II

- The Sepoy Rebellion of 1857-1858

- The Indian Mutiny The British Empire.

- Indian Mutiny Cranston Fine Arts

- The Revolt in India Marx & Engels in the New-York Daily Tribune, July 1857 - October 1858. Marxists.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.