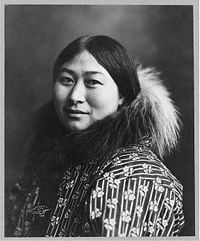

Eskimos or Esquimaux is a term referring to aboriginal people who, together with the related Aleuts, inhabit the circumpolar region, excluding Scandinavia and most of Russia, but including the easternmost portions of Siberia. They are culturally and biologically distinguishable from other Native Americans in the United States and Canada. There are two main groups of Eskimos: the Inuit of northern Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, and the Yupik, comprising speakers of four distinct Yupik languages and originating in western Alaska, in South Central Alaska along the Gulf of Alaska coast, and in the Russian Far East. The term "Eskimo" is not acceptable to those of Canada, who prefer Inuit or those of Greenland who refer to themselves as Kalaallit; however these terms are not appropriate for the Yupik, whose language and ethnicity is distinct from the Inuit. The Aleut culture developed separately from the Inuit around 4,000 years ago.

Although spread over a vast geographical area, there are many commonalities among the different Inuit and Yupik groups. Of particular note are their shamanistic beliefs and practices, although these have all but died out in recent times. Contemporary Eskimo generally live in settled communities with modern technology and houses instead of the traditional igloos, and have come to accept employment and other changes to their lifestyle although they continue to be self-sufficient through their hunting and fishing. The harsh climate still determines much about their lives, and they must maintain a balance between those traditions that have supported them well for generations and changes brought through contact with other cultures.

Terminology

The term Eskimo is broadly inclusive of the two major groups, the Inuit‚ÄĒincluding the Kalaallit (Greenlanders) of Greenland, Inuit and Inuinnait of Canada, and Inupiat of northern Alaska‚ÄĒand the Yupik peoples‚ÄĒthe Naukan of Siberia, the Yupik of Siberia in Russia and St. Lawrence Island in Alaska, the Yup'ik of Alaska, and the Alutiiq (Sug'piak or Pacific Eskimo) of southcentral Alaska. The anthropologist Thomas Huxley in On the Methods and Results of Ethnology (1865) defined the "Esquimaux race" to be the indigenous peoples in the Arctic region of northern Canada and Alaska. He described them to "certainly present a new stock" (different from the other indigenous peoples of North America). He described them to have straight black hair, dull skin complexion, short and squat, with high cheek bones and long skulls.

However, in Canada and Greenland, Eskimo is widely considered pejorative and offensive, and has been replaced overall by Inuit. The preferred term in Canada's Central Arctic is Inuinnait, and in the eastern Canadian Arctic Inuit. The language is often called Inuktitut, though other local designations are also used. The Inuit of Greenland refer to themselves as Greenlanders or, in their own language, Kalaallit, and to their language as Greenlandic or Kalaallisut.[1]

Because of the linguistic, ethnic, and cultural differences between Yupik and Inuit languages and peoples, there is still uncertainty as to what term encompassing all Yupik and Inuit people will be acceptable to all. There has been some movement to use Inuit as a term encompassing all peoples formerly described as Eskimo, Inuit and Yupik alike. Strictly speaking, however, Inuit does not refer to the Yupik peoples or languages of Alaska and Siberia. This is because the Yupik languages are linguistically distinct from the Inupiaq and other Inuit languages, and the peoples are ethnically and culturally distinct as well. The word Inuit does not occur in the Yupik languages of Alaska and Siberia.[1]

The term "Eskimo" is also used in some linguistic or ethnographic works to denote the larger branch of Eskimo-Aleut languages, the smaller branch being Aleut. In this usage, Inuit (together with Yupik, and possibly also Sireniki), are sub-branches of the Eskimo language family.

Origin of the term Eskimo

A variety of competing etymologies for the term "Eskimo" have been proposed over the years, but the most likely source is the Montagnais word meaning "snowshoe-netter." Since Montagnais speakers refer to the neighboring Mi'kmaq people using words that sound very much like eskimo, many researchers have concluded that this is the more likely origin of the word.[2][3][4]

An alternative etymology is "people who speak a different language." This was suggested by Jose Mailhot, a Quebec anthropologist who speaks Montagnais.[2]

The primary reason that the term Eskimo is considered derogatory is the perception that in Algonquian languages it means "eaters of raw meat," despite numerous opinions to the contrary.[2][3] [5]Nevertheless, it is commonly felt in Canada and Greenland that the term Eskimo is pejorative.[1][6]

Languages

Inuit languages comprise a dialect continuum, or dialect chain, that stretches from Unalaska and Norton Sound in Alaska, across northern Alaska and Canada, and east all the way to Greenland. Changes from western (Inupiaq) to eastern dialects are marked by the dropping of vestigial Yupik-related features, increasing consonant assimilation (for example, kumlu, meaning "thumb," changes to kuvlu, changes to kullu), and increased consonant lengthening, and lexical change. Thus, speakers of two adjacent Inuit dialects would usually be able to understand one another, but speakers from dialects distant from each other on the dialect continuum would have difficulty understanding one another.[7]

The Sirenikski language (extinct) is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family, but other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.[7]

The four Yupik languages, including Alutiiq (Sugpiaq), Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Naukan (Naukanski), and Siberian Yupik are distinct languages with phonological, morphological, and lexical differences, and demonstrating limited mutual intelligibility. Additionally, both Alutiiq Central Yup'ik have considerable dialect diversity. The northernmost Yupik languages‚ÄĒSiberian Yupik and Naukanski Yupik‚ÄĒare linguistically only slightly closer to Inuit than is Alutiiq, which is the southernmost of the Yupik languages. Although the grammatical structures of Yupik and Inuit languages are similar, they have pronounced differences phonologically, and differences of vocabulary between Inuit and any of one of the Yupik languages is greater than between any two Yupik languages.[7]

History

The earliest known Eskimo cultures were the Paleo-Eskimo, the Dorset and Saqqaq culture, which date as far back as 5,000 years ago. They appear to have developed from the Arctic small tool tradition culture. Genetic studies have shown that Paleo-Eskimos were of different stock from other Native Americans.[8] Later, around 1,000 years ago, people of the Thule culture arrived and expanded throughout the area.

Approximately 4,000 years ago, the Aleut (also known as Unangam) culture developed separately, not being considered part of the Eskimo culture today.

Approximately 1,500‚Äď2,000 years ago, apparently in Northwestern Alaska, two other distinct variations appeared. The Inuit language branch became distinct and in only several hundred years spread across northern Alaska, Canada, and into Greenland.

Today the two main groups of Eskimos are the Inuit of northern Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, and the Yupik in western Alaska and South Central Alaska along the Gulf of Alaska coast, and in the Russian Far East.

Culture

Eskimo groups cover a huge area stretching from Eastern Siberia through Alaska and Northern Canada (including Labrador Peninsula) to Greenland. There is a certain unity in the cultures of the Eskimo groups.

Although a large distance separated the Asiatic Eskimos and Greenland Eskimos, their shamanistic seances showed many similarities. Important examples of shamanistic practice and beliefs have been recorded at several parts of this vast area crosscutting continental borders. Also the usage of a specific shaman's language is documented among several Eskimo groups, including groups in Asia. Similar remarks apply for aspects of the belief system not directly linked to shamanism:

- tattooing[9]

- accepting the killed game as a dear guest visiting the hunter[10]

- usage of amulets[11]

- lack of totem animals[12][13]

Inuit

The Inuit inhabit the Arctic and Bering Sea coasts of Siberia and Alaska and Arctic coasts of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Quebec, Labrador, and Greenland. Until fairly recent times, there has been a remarkable homogeneity in the culture throughout this area, which traditionally relied on fish, sea mammals, and land animals for food, heat, light, clothing, tools, and shelter.

Canadian Inuit live primarily in Nunavut (a territory of Canada), Nunavik (the northern part of Quebec) and in Nunatsiavut (the Inuit settlement region in Labrador).

Inupiat

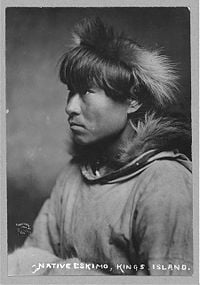

The Inupiat or Inupiaq people are the Inuit people of Alaska's Northwest Arctic and North Slope boroughs and the Bering Straits region, including the Seward Peninsula. Barrow, the northernmost city in the United States, is in the Inupiaq region. Their language is known as Inupiaq.

Inupiat people continue to rely heavily on subsistence hunting and fishing, including whaling. The capture of a whale benefits each member of a community, as the animal is butchered and its meat and blubber allocated according to a traditional formula. Even city-dwelling relatives thousands of miles away are entitled to a share of each whale killed by the hunters of their ancestral village. Muktuk, the skin of bowhead and other whales, is rich in vitamins A and C and contributes to good health in a population with limited access to fruits and vegetables.

In recent years the exploitation of oil and other resources has been an important revenue source for the Inupiat. The Alaska Pipeline connects the Prudhoe Bay wells with the port of Valdez in south central Alaska.

Inupiat people have grown more concerned in recent years that climate change is threatening their traditional lifestyle. The warming trend in the Arctic affects the Inupiaq lifestyle in numerous ways, for example: thinning sea ice makes it more difficult to harvest bowhead whale, seals, walrus, and other traditional foods; warmer winters make travel more dangerous and less predictable; later-forming sea ice contributes to increased flooding and erosion along the coast, directly imperiling many coastal villages. The Inuit Circumpolar Conference, a group representing indigenous peoples of the Arctic, has made the case that climate change represents a threat to their human rights.

Inupiaq groups often have a name ending in "miut." One example is the Nunamiut, a generic term for inland Inupiaq caribou hunters. During a period of starvation and influenza brought by American and European whaling crews, most of these moved to the coast or other parts of Alaska between 1890 and 1910.[14] A number of Nunamiut returned to the mountains in the 1930s. By 1950, most Nunamiut groups, like the Killikmiut, had coalesced in Anaktuvuk Pass, a village in northcentral Alaska. Some of the Nunamiut remained nomadic until the 1950s.

Inuvialuit

The Inuvialuit, or Western Canadian Inuit, are Inuit people who live in the western Canadian Arctic region. Like other Inuit, they are descendants of the Thule people. Their homeland - the Inuvialuit Settlement Region - covers the Arctic Ocean coastline area from the Alaskan border east to Amundsen Gulf and includes the western Canadian Arctic Islands. The land was demarked in 1984 by the Inuvialuit Final Agreement.

Kalaallit

Kalaallit is the Greenlandic term for the population living in Greenland. The singular term is kalaaleq. Their language is called Kalaallisut. About 80 to 90 percent of Greenland's population, or approximately 44,000 to 50,000 people, identify as being Kalaallit.[15][16]

The Kalaallit have a strong artistic tradition based on sewing animal skins and making masks. They are also known for an art form of figures called tupilaq or an "evil spirit object." Sperm whale ivory remains a valued medium for carving.[15]

Netsilik

The Netsilik Inuit (Netsilingmiut - People of the Seal) live predominately in the communities of Kugaaruk and Gjoa Haven of the Kitikmeot Region, Nunavut and to a smaller extent in Taloyoak and the north Qikiqtaaluk Region. They were, in the early twentieth century, among the last Northern indigenous people to encounter missionaries from the south. The missionaries introduced a system of written language called Qaniujaaqpait, based on syllabics, to the Netsilik in the 1920s. Eastern Canadian Inuit, among them the Netsilik, were the only Inuit peoples to adopt a syllabic system of writing.

The region where they live has an extremely long winter and stormy conditions in the spring, when starvation was a common danger. The cosmos of many other Eskimo cultures include protective guardian powers, but for the Netsilik the general hardship of life resulted in the extensive use of such measures, and even dogs could have amulets.[17] Unlike the Igluliks, the Netsilik used a large number of amulets. In one recorded instance, a young boy had eighty amulets, so many that he could hardly play.[18]

In addition one man had seventeen names taken from his ancestors that were intended to protect him.[19][20]

Among the Netsilik, tattooing was considered to provide power that could affect which world a woman goes to after her death.[21]

Tikigaq

The Tikigaq, an Inuit people, live two hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle, 330 miles (531 km) southwest of Barrow, Alaska, in an Inupiaq village of Point Hope, Alaska.[22] The Tikigaq are the oldest continuously settled Native American site on the continent. They are native whale hunters with centuries of experience co-existing with the Chukchi Sea that surrounds their Point Hope Promontory on three sides. "Tikigaq" means "index finger" in the Inupiaq language.

The Tikigaq relied on berries and roots for food, local willows for house frames, and moss or grass for lamp wicks and insulation. Today, distribution and movement of game, especially the beluga, Bowhead whale, caribou, seal, walrus, fur-bearing animals, polar bear and grizzly bear, directly effect the lives of Tikigaq.[23]

Yupik

The Yupik live along the coast of western Alaska, especially on the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta and along the Kuskokwim River (Central Alaskan Yup'ik), in southern Alaska (the Alutiiq) and in the Russian Far East and Saint Lawrence Island in western Alaska (the Siberian Yupik).

Alutiiq

The Alutiiq also called Pacific Yupik or Sugpiaq, are a southern, coastal branch of Yupik. They are not to be confused with the Aleuts, who live further to the southwest, including along the Aleutian Islands. They traditionally lived a coastal lifestyle, subsisting primarily on ocean resources such as salmon, halibut, and whale, as well as rich land resources such as berries and land mammals. Alutiiq people today live in coastal fishing communities, where they work in all aspects of the modern economy, while also maintaining the cultural value of subsistence. The Alutiiq language is relatively close to that spoken by the Yupik in the Bethel, Alaska area, but is considered a distinct language with two major dialects: the Koniag dialect, spoken on the Alaska Peninsula and on Kodiak Island, and the Chugach dialect, is spoken on the southern Kenai Peninsula and in Prince William Sound. Residents of Nanwalek, located on southern part of the Kenai Peninsula near Seldovia, speak what they call Sugpiaq and are able to understand those who speak Yupik in Bethel. With a population of approximately 3,000, and the number of speakers in the mere hundreds, Alutiiq communities are currently in the process of revitalizing their language.

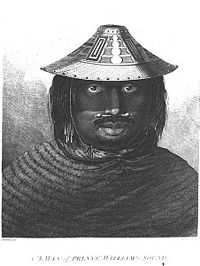

Chugach

Chugach is the name of the group of people in the region of the Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound. The Chugach people speak the Chugach dialect of the Alutiiq language.

The Chugach people gave their name to Chugach National Forest, the Chugach Mountains, and Alaska's Chugach State Park, all located in or near the traditional range of the Chugach people in southcentral Alaska. Chugach Alaska Corporation, an Alaska Native regional corporation created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, also derives its name from the Chugach people, many of whom are shareholders of the corporation.

Central Alaskan Yup'ik

Yup'ik, with an apostrophe, denotes the speakers of the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, who live in western Alaska and southwestern Alaska from southern Norton Sound to the north side of Bristol Bay, on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, and on Nelson Island. The use of the apostrophe in the name Yup'ik denotes a longer pronunciation of the p sound than found in Siberian Yupik. Of all the Alaska Native languages, Central Alaskan Yup'ik has the most speakers, with about 10,000 of a total Yup'ik population of 21,000 still speaking the language. There are five dialects of Central Alaskan Yup'ik, including General Central Yup'ik and the Egegik, Norton Sound, Hooper Bay-Chevak, Nunivak, dialects. In the latter two dialects, both the language and the people are called Cup'ik.[24]

Siberian Yupik (Yuit)

Siberian Yupik reside along the Bering Sea coast of the Chukchi Peninsula in Siberia in the Russian Far East[7] and in the villages of Gambell and Savoonga on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska.[25] The Central Siberian Yupik spoken on the Chukchi Peninsula and on Saint Lawrence Island is nearly identical. About 1,050 of a total Alaska population of 1,100 Siberian Yupik people in Alaska still speak the language, and it is still the first language of the home for most Saint Lawrence Island children. In Siberia, about 300 of a total of 900 Siberian Yupik people still learn the language, though it is no longer learned as a first language by children. Like the Netsiliks, the Yupik also practiced tattooing.[9]

Naukan

The Naukan originate on the the Chukot Peninsula in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in Siberia. It is estimated that about 70 of 400 Naukan people still speak the Naukanski.

Caribou Eskimos

‚ÄúCaribou Eskimos‚ÄĚ is a collective name for several groups of inland Eskimos (the Krenermiut, Aonarktormiut, Harvaktormiut, Padlermiut and Ahearmiut) living in an area bordered by the tree line and the west shore of Hudson Bay. They do not form a political unit and contacts between the groups are loose, but they share an inland lifestyle and exhibit some cultural unity. In the recent past, the Padlermiuts did have contact with the sea where they took part in seal hunts.[26]

The Caribou had a dualistic concept of the soul. The soul associated with respiration was called umaffia (place of life)[27] and the personal soul of a child was called tarneq (corresponding to the nappan of the Copper Eskimos). The tarneq was considered so weak that it needed the guardianship of a name-soul of a dead relative. The presence of the ancestor in the body of the child was felt to contribute to a more gentle behavior, especially among boys.[28] This belief amounted to a form of reincarnation.[29]

Because of their inland lifestyle, the Caribou had no belief concerning a Sea Woman. Other cosmic beings, variously named Sila or Pinga, take her place, controlling caribou instead of marine animals. Some groups made a distinction between the two figures, while others considered them the same. Sacrificial offerings to them could promote luck in hunting.[30]

Caribou shamans performed fortune-telling through qilaneq, a technique of asking a qila (spirit). The shaman placed his glove on the ground, and raised his staff and belt over it. The qila then entered the glove and drew the staff to itself. Qilaneq was practiced among several other Eskimo groups, where it was used to receive "yes" or "no" answers to questions.[31][32]

Religion

The term ‚Äúshamanism‚ÄĚ has been used for various distinct cultures. Classically, some indigenous cultures of Siberia were described as having shamans, but the term is now commonly used for other cultures as well. In general, the shamanistic belief systems accept that certain people (shamans) can act as mediators with the spirit world,[34] contacting the various entities (spirits, souls, and mythological beings) that populate the universe in those systems.

Shamanism among Eskimo peoples refers to those aspects of the various Eskimo cultures that are related to the shamans’ role as a mediator between people and spirits, souls, and mythological beings. Such beliefs and practices were once widespread among Eskimo groups, but today are rarely practiced, and it was already in the decline among many groups even in the times when the first major ethnological researches were done.[35] For example, at the end of the nineteenth century, Sagloq died, the last shaman who was believed to be able to travel to the sky and under the sea.[36]

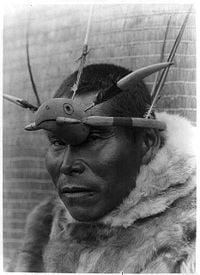

Shamans use various means, including music, recitation of epic, dance, and ritual objects[37] to interact with the spirit world - either for the benefit of the community or for doing harm. They may have spirits that assist them and may also travel to other worlds (or other aspects of this world). Most Eskimo groups had such a mediator function,[38] and the person fulfilling the role was believed to be able to command helping spirits, ask mythological beings (such as Nuliayuk, the Sea Woman) to ‚Äúrelease‚ÄĚ the souls of animals, enable the success of the hunt, or heal sick people by bringing back their ‚Äústolen‚ÄĚ souls. Shaman is used in an Eskimo context in a number of English-language publications, both academic and popular, generally in reference to the angakkuq among the Inuit. The /aňąli…£nal Āi/ of the Siberian Yupiks is also translated as ‚Äúshaman‚ÄĚ in both Russian and English literature.[39][40]

Shamanism among the Eskimo peoples exhibits some characteristic features not universal in shamanism, such as a dualistic concept of the soul in certain groups, and specific links between the living, the souls of hunted animals and dead people.[41] The death of either a person or a game animal requires that certain activities, such as cutting and sewing, be avoided to prevent harming their souls. In Greenland, the transgression of this death taboo could turn the soul of the dead into a tupilak, a restless ghost which scared game away. Animals were thought to flee hunters who violated taboos.[42]

The Eskimo belief system includes a number of supernatural beings. One such cosmic being known as Moon Man was thought to be friendly towards people and their souls as they arrive in celestial places.[43][44] This belief differs from that of the Greenland Eskimos, where the Moon’s anger was feared as a consequence of some taboo breaches.

Silap Inua was a sophisticated concept among Eskimo cultures (where its manifestation varied). Often associated with weather, it was conceived of as a power contained in people.[45] Among the Netsilik, Sila was imagined as male. The Netsilik (and Copper Eskimos) held that Sila originated as a giant baby whose parents were killed in combat between giants.[46]

The Sea Woman was known as Nuliayuk ‚Äúthe lubricous one.‚ÄĚ[47] If the people breached certain taboos, she would hold the marine animals in the tank of her lamp. When this happened the shaman had to visit her to beg for game. The Netsilik myth concerning her origin stated that she was an orphan girl who had been mistreated by her community. Several barriers had to be surmounted (such as a wall or a dog) and in some instances even the Sea Woman herself must be fought. If the shaman succeeds in appeasing her the animals will be released as normal.

The Iglulik variant of a myth explaining the Sea Woman’s origins involves a girl and her father. The girl did not want to marry. However, a bird managed to trick her into marriage and took her to an island. The girl's father managed to rescue his daughter, but the bird created a storm which threatened to sink their boat. Out of fear the father threw his daughter into the ocean, and cut her fingers as she tried to climb back into the boat. The cut joints became various sea mammals and the girl became a ruler of marine animals, living under the sea. Later on her remorseful father joined her. This local variant differs from several others, like that of the Netsiliks, which is about an orphan girl mistreated by her community.

Shamanic intiation

Unlike many Siberian traditions, in which spirits force individuals to become shamans, most Eskimo shamans choose this path.[48] Even when someone receives a ‚Äúcalling,‚ÄĚ that individual may refuse it.[49] The process of becoming an Eskimo shaman usually involves difficult learning and initiation rites, sometimes including a vision quest. Like the shamans of other cultures, some Eskimo shamans are believed to have special qualifications: they may have been an animal during a previous period, and thus be able to use their valuable experience for the benefit of the community.[50][51][52]

The initiation process varies from culture to culture. It may include:

- a specific kind of vision quest, such as among the Chugach.

- various kinds of out-of-body experiences such seeing oneself as skeleton, exemplified in Aua's (Iglulik) narration and a Baker Lake artwork [53][54]

Shamanic language

In several groups, shamans utilized a distinctly archaic version of the normal language interlaced with special metaphors and speech styles. Expert shamans could speak whole sentences differing from vernacular speech.[55] In some groups such variants were used when speaking with spirits invoked by the shaman, and with unsocialized babies who grew into the human society through a special ritual performed by the mother. Some writers have treated both phenomena as a language for communication with ‚Äúalien‚ÄĚ beings (mothers sometimes used similar language in a socialization ritual, in which the newborn is regarded as a little ‚Äúalien‚ÄĚ - just like spirits or animal souls).[56] The motif of a distinction between spirit and ‚Äúreal‚ÄĚ human is also present in a tale of Ungazigmit (subgroup of Siberian Yupik)[57] The oldest man asked the girl: ‚ÄúWhat, are you not a spirit?‚ÄĚ The girl answered: ‚ÄúI am not a spirit. Probably, are you spirits?‚ÄĚ The oldest man said: ‚ÄúWe are not spirits, [but] real human.‚ÄĚ

Soul dualism

The Eskimo shaman may fulfill multiple functions, including healing, curing infertile women, and securing the success of hunts. These seemingly unrelated functions can be grasped better by understanding the concept of soul dualism which, with some variation, underlies them.

- Healing

- It is held that the cause of sickness is soul theft, in which someone (perhaps an enemy shaman or a spirit) has stolen the soul of the sick person. The person remains alive because people have multiple souls, so stealing the appropriate soul causes illness or a moribund state rather than immediate death. It takes a shaman to retrieve the stolen soul.[58] According to another variant among Ammassalik Eskimos in East Greenland, the joints of the body have their own small souls, the loss of which causes pain.[59]

- Fertility

- The shaman provides assistance to the soul of an unborn child to allow its future mother to become pregnant.[60]

- Success of hunts

- When game is scarce the shaman can visit a mythological being who protects all sea creatures (usually the Sea Woman Sedna). Sedna keeps the souls of sea animals in her house or in a pot. If the shaman pleases her, she releases the animal souls thus ending the scarcity of game.

It is the shaman's free soul that undertakes these spirit journeys (to places such as the land of dead, the home of the Sea Woman, or the moon) whilst his body remains alive. When a new shaman is first initiated, the initiator extracts the shaman's free soul and introduces it to the helping spirits so that they will listen when the new shaman invokes them[61]; or according to an another explanation (that of the Iglulik shaman Aua) the souls of the vital organs of the apprentice must move into the helping spirits: the new shaman should not feel fear of the sight of his new helping spirits.[62]

A human child's developing soul is usually ‚Äúsupported‚ÄĚ by a name-soul: a baby can be named after a deceased relative, invoking the departed name-soul which will then accompany and guide the child until adolescence. This concept of inheriting name-souls amounts to a sort of reincarnation among some groups, such as the Caribou Eskimos.

The boundary between shaman and lay person was not always clearly demarcated. Non-shamans could also experience hallucinations,[63] almost every Eskimo may report memories about ghosts, animals in human form, little people living in remote places. Experiences such as hearing voices from ice or stones were discussed as readily as everyday hunting adventures.[64] The ability to have and command helping spirits was characteristic of shamans, but non-shamans could also profit from spirit powers through the use of amulets.[65]

Contemporary Eskimo

Eskimos throughout the U.S. and Canada live in largely settled communities, working for corporations and unions, and have come to embrace other cultures and contemporary conveniences in their lifestyle. Although still self-sufficient through their time-honored traditions of fishing and hunting, the Eskimos are no longer completely dependent on their own arctic resources. Many have adopted the use of modern technology in the way of snowmobiles instead of dog sleds, and modern houses instead of igloos.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 granted Alaska natives some 44 million acres of land and established native village and regional corporations to encourage economic growth. In 1990 the Eskimo population of the United States was approximately 57,000, with most living in Alaska. There are over 33,000 Inuit in Canada (the majority living in Nunavut), the Northwest Territories, North Quebec, and Labrador. Nunavut was created out of the Northwest Territories in 1999 as a predominately Inuit territory, with political separation. A settlement with the Inuit of Labrador established (2005) Nunatsiavut, which is a self-governing area in north and central east Labrador. There are also Eskimo populations in Greenland and Siberia.

In 2011, John Baker became the first Inupiat Eskimo, and the first Native Alaskan since 1976, to win the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, setting a new record time.[66] He was greeted by drummers and dancers from his Inupiat tribe, many relatives and supporters from his home town of Kotzebue, as well as Denise Michels, the first Inupiat to be elected mayor of Nome.[67]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Lawrence Kaplan, "Inuit or Eskimo: Which names to use?". Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 2002. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 J. Mailhot, "L'√©tymologie de ¬ęEsquimau¬Ľ revue et corrig√©e." Etudes Inuit/Inuit Studies 2(2) (1978):59‚Äď70.

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 Ives Goddard, "Synonymy." In David Damas (ed.) Handbook of North American Indians:Volume 5 Arctic (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1985, 978-0874741858), 5-7.

- ‚ÜĎ Lyle Campbell, American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 394.

- ‚ÜĎ Setting the Record Straight About Native Languages: What Does "Eskimo" Mean In Cree? Native Languages of the Americas website. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Pamela R. Stern, Historical Dictionary of the Inuit (Scarecrow Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0810850583).

- ‚ÜĎ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Lawrence Kaplan, "Comparative Yupik and Inuit". Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Daniel Cressey, Unexpected origin of an early Eskimo Nature News, May 29, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ 9.0 9.1 Lars Krutak, Tattoos of the early hunter-gatherers of the Arctic The Vanishing Tatoo. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ E. S. Rubcova, Materials on the Language and Folklore of the Eskimoes, Vol. I, Chaplino Dialect. (Moscow & Leningrad: Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1954), 218

- ‚ÜĎ Rubcova (1954), 380

- ‚ÜĎ (Russian) A radio interview with Russian scientists about Asian Eskimos transcript (in Russian)

- ‚ÜĎ A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, "The Sociological Theory of Totemism." In Structure and Function in Primitive Society. (Glencoe: The Free Press, 1965).

- ‚ÜĎ John Bockstoce, Whales, Ice, & Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic. (University of Washington Press, 1995).

- ‚ÜĎ 15.0 15.1 Ingo Hessel, Arctic Spirit (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2006, ISBN 978-1553651895).

- ‚ÜĎ Geoffery Baldacchino, Extreme Tourism: Lessons from the World's Cold Water Islands (Elsevier Science, 2006, ISBN 978-0080446561), 101.

- ‚ÜĎ Knud Rasmussen, Thulei utaz√°s. (Vil√°gj√°r√≥k) (Budapest: Gondolat, 1965. (Hungarian translation of German original 1926), 268.

- ‚ÜĎ I. Kleivan and B. Sonne, "Arctic Peoples," in Eskimos: Greenland and Canada, section VIII, fascicle 2. Institute of Religious Iconography, State University Groningen. (Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1985. Iconography of religions), 43

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen, 1965.

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 15

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen 1965, 256, 279

- ‚ÜĎ Point Hope, Alaska Tikigaq Corporation: An Alaska Native Village Corporation. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ I√Īupiaq People Tikigaq Corporation: An Alaska Native Village Corporation. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Alaska Native Language Center, "Central Alaskan Yup'ik." Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Alaska Native Language Center. (2001-12-07). "Siberian Yupik." Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Anchorage. Retrieved on 2007-04-06.

- ‚ÜĎ Gabus 1970:145

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:18

- ‚ÜĎ Gabus 1970:111

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:18, Gabus 1970:212

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan & Sonne 1985:31, 36

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen 1965:108, Kleivan & Sonne 1985:26

- ‚ÜĎ Gabus 1970:227‚Äď228

- ‚ÜĎ Ann Fienup-Riordan. Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 206.

- ‚ÜĎ Mih√°ly Hopp√°l. S√°m√°nok Eur√°zsi√°ban. (Budapest: Akad√©miai Kiad√≥, 2005. ‚ÄúShamans in Eurasia‚ÄĚ), 45‚Äď50

- ‚ÜĎ Daniel Merkur, Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1985), 132

- ‚ÜĎ Merkur, 134

- ‚ÜĎ Hopp√°l 2005:14

- ‚ÜĎ MenovŇ°ńćikov, "Popular Conceptions, Religious Beliefs and Rites of the Asiatic Eskimoes," translated into English and published in: Vilmos Di√≥szegi and Mih√°ly Hopp√°l, [1968] Folk Beliefs and Shamanistic Traditions in Siberia. (Budapest: Akad√©miai Kiad√≥, 1996.) 1968:442

- ‚ÜĎ Rubcova 1954, 203‚Äď219

- ‚ÜĎ MenovŇ°ńćikov 1968, 442

- ‚ÜĎ Vitebsky 1996, 14

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 12‚Äď13, 18‚Äď21, 23

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 30

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen 1965, 279

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen 1965, 106

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 31

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 27

- ‚ÜĎ Sam Di√≥szegi. Vilmos. Samanizmus.√Člet √©s Tudom√°ny Kisk√∂nyvt√°r (Budapest: Gondolat, 1962)

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985:24

- ‚ÜĎ Heinz Bar√ľske, ‚ÄúDie Seele, die alle Tiere durchwanderte,‚ÄĚ in Eskimo M√§rchen. (tale 7). (D√ľsseldorf: Eugen Diederichs, 1969, 19‚Äď23

- ‚ÜĎ Vitebsky 1996, 106

- ‚ÜĎ Knud Rasmussen, ‚ÄúThe Soul that Lived in the Bodies of All Beasts,‚ÄĚ in Eskimo Folk-Tales, trans. W. Worster, with illustrations by native Eskimo artists. (London: Gyldendal, 1921), 100.

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 38, plate XXIII

- ‚ÜĎ Vitebsky 1996, 18

- ‚ÜĎ Merkur 1985, 7

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne 1985, 6, 14, 33

- ‚ÜĎ Rubcova 1954, 175, 34‚Äď38

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen 1965, 177

- ‚ÜĎ Gabus, 274

- ‚ÜĎ Merkur 1985, 4

- ‚ÜĎ Merkur 1985, 121

- ‚ÜĎ Rasmussen 1965, 170

- ‚ÜĎ Merkur 1985, 41‚Äď42

- ‚ÜĎ Gabus 1970, 203

- ‚ÜĎ Kleivan and Sonne, 1985.

- ‚ÜĎ Iditarod Staff, The Iditarod Has a New Champion: Kotzebue Alaska‚Äôs John Baker Eye on the Trail (March 15, 2011).

- ‚ÜĎ Yereth Rosen, Alaska Native wins Iditarod for 1st time since 1976 Reuters (March 15, 2011).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bockstoce, John. Whales, Ice, & Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0295974477

- Campbell, Lyle. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195140507

- Damas, David (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 5 Arctic. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0874741858

- Di√≥szegi, Vilmos. Samanizmus. Budapest: Gondolat, 1962. √Člet √©s Tudom√°ny Kisk√∂nyvt√°r

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

- Gabus, Jean. A karibu eszkimók. Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó, 1970. Translation of the original: Vie et coutumes des Esquimaux Caribous. Lausanne: Libraire Payot, 1944.

- Gubser, Nicholas. The Nunamiut Eskimos, Hunters of Caribou, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1969. ASIN B000WQ6YFC

- Hoppál, Mihály. Sámánok Eurázsiában. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2005. In Hungarian ISBN 9630582953

- Ingstad, Helge. Nunamiut; among Alaska's Inland Eskimos. Countryman, 2006. ISBN 978-0881507614

- Kleivan, Inge, and Birgitte Sonne. Eskimos: Greenland and Canada. Brill Academic Pub, 1997. ISBN 9004071601

- Mauss, Marcel. Translated, with a foreword by James J. Fox. Seasonal variations of the Eskimo: a study in social morphology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 2004 (original 1950). ISBN 978-0415330350

- MenovŇ°ńćikov, G. A. (–ď. –ź. –ú–Ķ–Ĺ–ĺ–≤—Č–ł–ļ–ĺ–≤). Popular Conceptions, Religious Beliefs and Rites of the Asiatic Eskimoes, Translated into English and published in: Vilmos Di√≥szegiand, Folk Beliefs and Shamanistic Traditions in Siberia. Budapest: Akad√©miai Kiad√≥, 1996 (original 1968). ISBN 978-9630569651

- Merkur, Daniel. Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. Routledge, 2016 (original 1985). ISBN 978-1138964471

- Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. Structure and Function in Primitive Society. Glencoe: The Free Press, 1965. ISBN 978-0029256206

- Rasmussen, Knud (ed.) ‚ÄúThe Soul that Lived in the Bodies of All Beasts,‚ÄĚ in Eskimo Folk-Tales, ed. and trans. W. Worster, with illustrations by native Eskimo artists. London: Gyldendal, 1921.

- Rasmussen, Knud. Thulefahrt Frankfurt am Main: Frankurter SocietńÉts-Druckerei, 1926. (in German)

- Rasmussen, Knud. Thulei utazás. (Világjárók) Budapest: Gondolat, 1965. (Hungarian translation of Rasmussen 1926).

- Rasmussen, Knud (ed.). Eskimo Folk-Tales. Dodo Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1409987253

- Rubcova, E. S. Materials on the Language and Folklore of the Eskimoes (Vol. I, Chaplino Dialect) Moscow & Leningrad: Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1954. ASIN B00460ZHEY (Original data: –†—É–Ī—Ü–ĺ–≤–į –ē. –°. –ú–į—ā–Ķ—Ä–ł–į–Ľ—č –Ņ–ĺ —Ź–∑—č–ļ—É –ł —Ą–ĺ–Ľ—Ć–ļ–Ľ–ĺ—Ä—É —ć—Ā–ļ–ł–ľ–ĺ—Ā–ĺ–≤ (—á–į–Ņ–Ľ–ł–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–ł–Ļ –ī–ł–į–Ľ–Ķ–ļ—ā) 1954 –ź–ļ–į–ī–Ķ–ľ–ł—Ź –Ě–į—É–ļ –°–°–°–† –ú–ĺ—Ā–ļ–≤–į ‚ÄĘ –õ–Ķ–Ĺ–ł–Ĺ–≥—Ä–į–ī.)

- Sprott, Julie E. Raising Young Children in an Alaskan I√Īupiaq Village The Family, Cultural, and Village Environment of Rearing. Praeger, 2003. ISBN 0897897897

- Stern, Pamela R. Historical Dictionary of the Inuit. Scarecrow Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0810850583

- Vitebsky, Piers. The Shaman: Voyages of the Soul - Trance, Ecstasy and Healing from Siberia to the Amazon. London: Duncan Baird, 2001. ISBN 1903296188

- Vitebsky, Piers. A s√°m√°n B√∂lcsess√©g ‚ÄĘ hit ‚ÄĘ m√≠tosz Budapest: Magyar K√∂nyvklub, 1996 Helikon Kiad√≥ ISBN 963548254X (Translation of the original: Secrets of the Shaman (Living Wisdom) London: Duncan Baird, 1995. ISBN 0705430618

- Voigt, Mikl√≥s. Vil√°gnak kezdet√©tŇĎl fogva / T√∂rt√©neti folklorisztikai tanulm√°nyok. Budapest: Universitas K√∂nyvkiad√≥, 2000. ISBN 978-9639104396 (in Hungarian) In it, on pp 41‚Äď45: S√°m√°n‚ÄĒa sz√≥ √©s √©rtelme (The etymology and meaning of word shaman).

External links

All links retrieved March 20, 2024.

- The Peoples of the Red Book The Asiatic (Siberian) Eskimos (in English)

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections ‚Äď Frank H. Nowell Photographs Photographs documenting scenery, towns, businesses, mining activities, Native Americans, and Eskimos in the vicinity of Nome, Alaska from 1901-1909.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections ‚Äď Alaska and Western Canada Collection Images documenting Alaska and Western Canada, primarily the provinces of Yukon Territory and British Columbia depicting scenes of the Gold Rush of 1898, city street scenes, Eskimo and Native Americans of the region, hunting and fishing, and transportation.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections ‚Äď Arthur Churchill Warner Photographs Includes images of Eskimos from 1898-1900.

- Wisdom from Eskimo-Kalaallit Elder, Angaangaq

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.