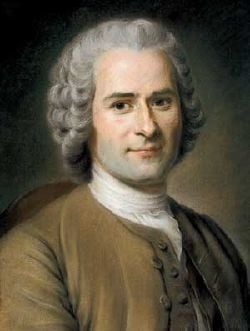

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau |

|---|

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

|

| Born |

| June 28, 1712 Geneva, Switzerland |

| Died |

| July 2, 1778 Ermenonville, France |

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (June 28, 1712 â July 2, 1778) was a Franco-Swiss philosopher of the Enlightenment whose political ideas influenced the French Revolution, the development of socialist and democratic theory, and the growth of nationalism. His legacy as a radical and revolutionary is perhaps best described by the most famous line in his most famous book, The Social Contract: "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains." Rousseau's social contract theory, based on Thomas Hobbes and John Locke would serve as one of the bases of modern democracy, while his Emile would heavily influence modern education, and his Confessions would serve as a model for modern autobiography.

What Rousseeau meant by "being in chains" was that society â and particularly the modernizing, industrializing society of his own time â was a negative influence on human development. Rousseau believed that original man, in his natural state, was entirely free and virtuous. It was only when human beings gathered together and formed societies that they became capable of jealousy, greed, malice, and all the other vices which we are capable of committing. In this respect, Rousseau appears to have created a philosophical basis for the staunchly individualistic thinkers like Emerson, and the major literary writers of Romanticism throughout Europe who all argued, in one way or another, that if human beings were able to return to their "natural state" they would be happy forever after.

However, Rousseau's ideas were not that simplistic. Although he felt that society (especially monarchial society) had exerted a corrupting influence on humanity, he believed that if humanity was guided only by natural instincts it would inevitably descend into brutality. Rousseau believed that what was needed by humankind was not a return to primitivism, but a complete reevaluation of the social order. Although Rousseau is often labeled as a "proto-socialist" political thinker whose views would inspire the socialist theories of Karl Marx, the form of government which Rousseau would spend his life fighting for was not socialism but direct, non-representative democracy. Nor was Rousseau an atheistic thinker like Marx. Although his views on religion in his own time were highly controversial â in the Social Contract he infamously wrote that followers of Jesus would not make good citizens â what Rousseau meant by this was that religious feeling, like the naturally good instincts of man, would not fit in with a society of oppression and injustice.

Rousseau's contributions to political theory have been invaluable to the development of democracy. Historians will note that it is no coincidence that the French Revolution took place shortly after his death. However, Rousseau was more than just a conventional philosopher, and while his legacy to politics is immense it is important not to disregard the other avenues of his thought. Rousseau was also a novelist, memoirist, and musician. He had interests ranging from art and painting to the modern sciences. He was a "Man of the Enlightenment" in the same vein as Goethe in Germany and Coleridge in England. Any assessment of Rousseau's massive influence on French and European thought must take into account the impact of all of his writings.

Biography

Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, and throughout his life described himself as a citizen of Geneva. His mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, died a week later due to complications from childbirth, and his father Isaac, a failed watchmaker, abandoned him in 1722 to avoid imprisonment for fighting a duel. His childhood education consisted solely of reading Plutarch's Lives and Calvinist sermons. Rousseau was beaten and abused by the pastor's sister who had taken responsibility for Rousseau after his father absconded.

Rousseau left Geneva on March 14, 1728, after several years of apprenticeship to a notary and then an engraver. He then met Françoise-Louise de Warens, a French Catholic baroness who would later became his lover, even though she was twelve years his elder. Under the protection of de Warens, he converted to Catholicism.

Rousseau spent a few weeks in a seminary and beginning in 1729, six months at the Annecy Cathedral choir school. He also spent much time travelling and engaging in a variety of professions; for instance, in the early 1730s he worked as a music teacher in Chambéry. In 1736 he enjoyed a last stay with de Warens near Chambéry, which he found idyllic, but by 1740 he had departed again, this time to Lyon to tutor the young children of Gabriel Bonnet de Mably.

In 1742 Rousseau moved to Paris in order to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of musical notation he had invented, based on a single line displaying numbers that represented intervals between notes and dots and commas that indicated rhythmic values. The system was intended to be compatible with typography. The Academy rejected it as useless and unoriginal.

From 1743 to 1744, he was secretary to the French ambassador in Venice, whose republican government Rousseau would refer to often in his later political work. After this, he returned to Paris, where he befriended and lived with ThérÚse Lavasseur, an illiterate seamstress who bore him five children. As a result of his theories on education and child-rearing, Rousseau has often been criticized by Voltaire and modern commentators for putting his children in an orphanage as soon as they were weaned. In his defense, Rousseau explained that he would have been a poor father, and that the children would have a better life at the foundling home. Such eccentricities were later used by critics to vilify Rousseau as socially dysfunctional in an attempt to discredit his theoretical work.

While in Paris, he became friends with Diderot and beginning in 1749 contributed several articles to his Encyclopédie, beginning with some articles on music. His most important contribution was an article on political economy, written in 1755. Soon after, his friendship with Diderot and the Encyclopedists would become strained.

In 1749, on his way to Vincennes to visit Diderot in prison, Rousseau heard of an essay competition sponsored by the Académie de Dijon, asking the question whether the development of the arts and sciences has been morally beneficial. Rousseau's response to this prompt, answering in the negative, was his 1750 "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences," which won him first prize in the contest and gained him significant fame.

Rousseau claimed that during the carriage ride to visit Diderot, he had experienced a sudden inspiration on which all his later philosophical works were based. This inspiration, however, did not cease his interest in music and in 1752 his opera Le Devin du village was performed for King Louis XV.

In 1754, Rousseau returned to Geneva where he reconverted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship. In 1755 Rousseau completed his second major work, the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men. Beginning with this piece, Rousseau's work found him increasingly in disfavor with the French government.

Rousseau, in 1761 published the successful romantic novel Julie, ou la nouvelle HĂ©loĂŻse (The New Heloise). In 1762 he published two major books, first The Social Contract (Du Contrat Social) in April and then Ămile, or On Education in May. Both books criticized religion and were banned in both France and Geneva. Rousseau was forced to flee arrest and made stops in both Bern and Motiers in Switzerland. While in Motiers, Rousseau wrote the Constitutional Project for Corsica (Projet de Constitution pour la Corse).

Facing criticism in Switzerlandâhis house in Motiers was stoned in 1765âhe took refuge with the philosopher David Hume in Great Britain, but after 18 months he left because he believed Hume was plotting against him. Rousseau returned to France under the name "Renou," although officially he was not allowed back in until 1770. In 1768 he married ThĂ©rĂšse, and in 1770 he returned to Paris. As a condition of his return, he was not allowed to publish any books, but after completing his Confessions, Rousseau began private readings. In 1771 he was forced to stop, and this book, along with all subsequent ones, was not published until 1782, four years after his death.

Rousseau continued to write until his death. In 1772, he was invited to present recommendations for a new constitution for Poland, resulting in the Considerations on the Government of Poland, which was to be his last major political work. In 1776 he completed Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques and began work on the Reveries of the Solitary Walker. In order to support himself through this time, he returned to copying music. Because of his prudential suspicion, he did not seek attention or the company of others. While taking a morning walk on the estate of the Marquis de Giradin at Ermenonville (28 miles northeast of Paris), Rousseau suffered a hemorrhage and died on July 2, 1778.

Rousseau was initially buried on the Ile des Peupliers. His remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794, 16 years after his death. The tomb was designed to resemble a rustic temple, to recall Rousseau's theories of nature. In 1834, the Genevan government reluctantly erected a statue in his honor on the tiny Ile Rousseau in Lake Geneva. In 2002, the Espace Rousseau was established at 40 Grand-Rue, Geneva, Rousseau's birthplace.

Philosophy

Nature vs. society

Rousseau saw a fundamental divide between society and human nature. Rousseau contended that man was good by nature, a "noble savage" when in the state of nature (the state of all the "other animals," and the condition humankind was in before the creation of civilization and society), but is corrupted by society. He viewed society as artificial and held that the development of society, especially the growth of social interdependence, has been inimical to the well-being of human beings.

Society's negative influence on otherwise virtuous men centers, in Rousseau's philosophy, on its transformation of amour de soi, a positive self-love comparable to Emerson's "self-reliance," into amour-propre, or pride. Amour de soi represents the instinctive human desire for self-preservation, combined with the human power of reason. In contrast, amour-propre is not natural but artificial and forces man to compare himself to others, creating unwarranted fear and allowing men to take pleasure in the pain or weakness of others. Rousseau was not the first to make this distinction; it had been invoked by, among others, Vauvenargues.

In "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences" Rousseau argued that the arts and sciences had not been beneficial to humankind, because they were advanced not in response to human needs but as the result of pride and vanity. Moreover, the opportunities they created for idleness and luxury contributed to the corruption of man. He proposed that the progress of knowledge had made governments more powerful and had crushed individual liberty. He concluded that material progress had actually undermined the possibility of sincere friendship, replacing it with jealousy, fear and suspicion.

His subsequent Discourse on Inequality tracked the progress and degeneration of mankind from a primitive state of nature to modern society. He suggested that the earliest human beings were isolated semi-apes who were differentiated from animals by their capacity for free will and their perfectibility. He also argued that these primitive humans were possessed of a basic drive to care for themselves and a natural disposition to compassion or pity. As humans were forced to associate together more closely, by the pressure of population growth, they underwent a psychological transformation and came to value the good opinion of others as an essential component of their own well being. Rousseau associated this new self-awareness with a golden age of human flourishing. However, the development of agriculture and metallurgy, private property and the division of labor led to increased interdependence and inequality. The resulting state of conflict led Rousseau to suggest that the first state was invented as a kind of social contract made at the suggestion of the rich and powerful. This original contract was deeply flawed as the wealthiest and most powerful members of society tricked the general population, and thus instituted inequality as a fundamental feature of human society. Rousseau's own conception of the social contract can be understood as an alternative to this fraudulent form of association. At the end of the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau explains how the desire to have value in the eyes of others, which originated in the golden age, comes to undermine personal integrity and authenticity in a society marked by interdependence, hierarchy, and inequality.

Political theory

The Social Contract

Perhaps Rousseau's most important work is The Social Contract, which outlines the basis for a legitimate political order. Published in 1762 it became one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the Western tradition. It developed some of the ideas mentioned in an earlier work, the article Economie Politique, featured in Diderot's Encyclopédie. Rousseau claimed that the state of nature eventually degenerates into a brutish condition without law or morality, at which point the human race must adopt institutions of law or perish. In the degenerate phase of the state of nature, man is prone to be in frequent competition with his fellow men while at the same time becoming increasingly dependent on them. This double pressure threatens both his survival and his freedom. According to Rousseau, by joining together through the social contract and abandoning their claims of natural right, individuals can both preserve themselves and remain free. This is because submission to the authority of the general will of the people as a whole guarantees individuals against being subordinated to the wills of others and also ensures that they obey themselves because they are, collectively, the authors of the law. While Rousseau argues that sovereignty should be in the hands of the people, he also makes a sharp distinction between sovereign and government. The government is charged with implementing and enforcing the general will and is composed of a smaller group of citizens, known as magistrates. Rousseau was bitterly opposed to the idea that the people should exercise sovereignty via a representative assembly. Rather, they should make the laws directly. It has been argued that this would prevent Rousseau's ideal state being realized in a large society, though in modern times, communication may have advanced to the point where this is no longer the case. Much of the subsequent controversy about Rousseau's work has hinged on disagreements concerning his claims that citizens constrained to obey the general will are thereby rendered free.

Education

Rousseau set out his views on education in Ămile, a semi-fictitious work detailing the growth of a young boy of that name, presided over by Rousseau himself. He brings him up in the countryside, where, he believes, humans are most naturally suited, rather than in a city, where we only learn bad habits, both physical and intellectual. The aim of education, Rousseau says, is to learn how to live, and this is accomplished by following a guardian who can point the way to good living.

The growth of a child is divided into three sections, first to the age of about 12, when calculating and complex thinking is not possible, and children, according to his deepest conviction, live like animals. Second, from 12 to about 15, when reason starts to develop, and finally from the age of 15 onwards, when the child develops into an adult. At this point, Emile finds a young woman to complement him.

The book is based on Rousseau's ideals of healthy living. The boy must work out how to follow his social instincts and be protected from the vices of urban individualism and self-consciousness.

Religion

Rousseau was most controversial in his own time for his views on religion. His view that man is good by nature conflicts with the doctrine of original sin and his theology of nature expounded by the Savoyard Vicar in Ămile led to the condemnation of the book in both Calvinist Geneva and Catholic Paris. In the Social Contract he claims that true followers of Jesus would not make good citizens. This was one of the reasons for the book's condemnation in Geneva. Rousseau attempted to defend himself against critics of his religious views in his Letter to Christophe de Beaumont, the Archbishop of Paris.

Legacy

Although the French Revolution started as liberal, in 1793 Maximilien Robespierre, a follower of Rousseau, took power and executed the liberal revolution leaders and anybody whose popularity threatened his position.

Writers such as Benjamin Constant and Hegel blamed this Reign of Terror and Robespierre's totalitarianism on Rousseau, because Rousseau's ideology could be seen to justify a totalitarian regime without civil rights, such as the protection of the body and the property of the individual from the decisions of the government. However, Rousseau argued for direct democracy instead of representative democracy, and some people believe that such terrible decisions would not have been made in direct democracy and hence civil rights would not be needed. Robespierre also shared Rousseau's (proto)socialist thoughts.

Rousseau was one of the first modern writers to seriously attack the institution of private property, and therefore is sometimes considered a forebearer of modern socialism and communism (see Karl Marx, though Marx rarely mentions Rousseau in his writings). Rousseau also questioned the assumption that majority will is always correct. He argued that the goal of government should be to secure freedom, equality, and justice for all within the state, regardless of the will of the majority (see democracy).

One of the primary principles of Rousseau's political philosophy is that politics and morality should not be separated. When a state fails to act in a moral fashion, it ceases to function in the proper manner and ceases to exert genuine authority over the individual. The second important principle is freedom, which the state is created to preserve.

Rousseau's ideas about education have profoundly influenced modern educational theory. In Ămile he differentiates between healthy and "useless" crippled children. Only a healthy child can be the rewarding object of any educational work. He minimizes the importance of book-learning, and recommends that a child's emotions should be educated before his reason. He placed a special emphasis on learning by experience. John Darling's 1994 book Child-Centred Education and its Critics argues that the history of modern educational theory is a series of footnotes to Rousseau.

In his main writings Rousseau identifies nature with the primitive state of savage man. Later he took nature to mean the spontaneity of the process by which man builds his egocentric, instinct-based character and his little world. Nature thus signifies interiority and integrity, as opposed to that imprisonment and enslavement which society imposes in the name of progressive emancipation from coldhearted brutality.

Hence, to go back to nature means to restore to man the forces of this natural process, to place him outside every oppressing bond of society and the prejudices of civilization. It is this idea that made his thought particularly important in Romanticism, though Rousseau himself is sometimes regarded as a figure of The Enlightenment.

Almost all other Enlightenment philosophers argued for reason over mysticism; liberalism, free markets, individual freedom; human rights including the freedom of speech and press; progress, science and arts, while Rousseau obtained enormous fame by arguing for the contrary, mysticism, (proto)socialism, and no check on the power of the sovereign over the body and the property of an individual. He said that science originated in vices, that man had been better in the Stone Age and that censorship should be exercised to prevent people from being misled.

Literature

Rousseau's contributions to the French literature of his time were immense. His novel Heliose was tremendously popular among 18th century Parisians, and became a "must-read" book among the French literati, much like Goethe's Sorrows of Young Werther. However, as a novelist Rousseau has fallen considerably out of favor since his own time. While certainly a gifted writer and indisputably a major political philosopher, Rousseau's gifts, most scholars agree, did not extend very well into fiction-writing. As many contemporary scholars have pointed out, Rousseau's fiction has the unfortunate tendency to turn into poorly disguised philosophizing.

However, Rousseau's rhetorical style was absolutely perfect for the then-new genre of non-fictional writing. Towards the end of his life Rousseau began to compose essayish memoir pieces, influenced no doubt by the monumental French essayist Montaigne. Like Montaigne, Rousseau had a talent for alternating his philosophical ideas with a non-chalant and almost chatty recollection of his own life and deeds. Rousseau's greatest contribution in this vein, his Confessions (which, in addition to Montaigne, had been modelled explicitly on the Confessions of Saint Augustine) was one of the first major autobiographies to appear in the West in any language, and it was tremendously influential on a wide range of European writers. Rousseau's conversational (yet deeply insightful) style would be cited as an influence by such major literary figures as Tolstoy, Goethe, and Trollope.

His treatise on acting was far ahead of its time.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Robinson, Dave & Judy Groves. 2003. Introducing Political Philosophy. London: Icon Books. ISBN 184046450X.

Major works

- Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (Discours sur les sciences et les arts), 1750

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy, 1752

- Le Devin du Village: an opera, 1752

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes), 1754

- Discourse on Political Economy, 1755

- Letters to M. D'Alembert on the Theater, 1758 (Lettre Ă D'Alembert sur les spectacles)

- Julie, or the New Heloise (Julie ou la nouvelle HĂ©loĂŻse), 1761

- Ămile: or, on Education (Ămile ou de l'Ă©ducation), 1762

- The Creed of a Savoyard Priest, 1762 (in Ămile)

- The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Right (Du contrat social), 1762

- Four Letters to M. de Malesherbes, 1762

- Letters Written from the Mountain, 1764 (Lettres de la montagne)

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Les Confessions), 1770, published 1782

- Constitutional Project for Corsica, 1772

- Considerations on the Government of Poland, 1772

- Reveries of a Solitary Walker, incomplete, published 1782 (RĂȘveries du promeneur solitaire)

- Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques, published 1782

Editions in English

- Collected Writings, ed. Roger D. Masters and Christopher Kelly, Dartmouth: University Press of New England, 1990-2005, 11 vols. (Does not as yet include Ămile.)

- Emile, Everyman Press, 1992.

External links

All links retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Mondo Politico Library's presentation of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's book, The Social Contract (G.D.H. Cole translation; full text)

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau English translation, as published by Project Gutenberg, 2004 [EBook #3913]

- Rousseau Association/Association Rousseau, a bilingual association (English and French) devoted to the study of Rousseau's life and works

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau page at Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau page at Philosophy Pages

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.