The Society of Jesus (Latin: Societas Iesu, "S.J.," "S.I." also called the "Jesuits") is a Roman Catholic religious order known for its rigorous scholarship and apostolic zeal. Founded in 1540 by Saint Ignatius of Loyola (a former knight who became a priest), the Jesuits became renowned for their work in the fields of missionary outreach, direct evangelization, intellectual research, and education (schools, colleges, universities, seminaries, theological faculties, cultural pursuits). Included among their famous members are Saint Francis Xavier and Peter Faber.

Jesuits are required to pledge allegiance to the Pope but their intellectual independence and separate leader in the order (sometimes called the "Black Pope" after the color of the Jesuit habit) has occasionally lead them to be seen as a threat to the Vatican. Given their immense learning, the Jesuits were occasionally entangled in the debates of geopolitics, which did not always go well for them. At times, the order was seen as a dangerous and powerful movement within the church and occasionally repressed by the Papacy.

Today, the Jesuits are a well-respected and flourishing religious order with ministries in 112 nations on six continents. Their headquarters, known as the General Curia, is found in Rome. Jesuits continue to be actively engaged in social justice and human rights issues in modern times, especially interreligious dialogue, and Liberation theology. In 2013, Jorge Mario Bergoglio became the first Jesuit Pope, taking the name Pope Francis.

History

Founding

On August 15, 1534, Ignatius of Loyola (born Ăñigo LĂłpez de Loyola), a Spaniard of Basque origin, and six other students at the University of Paris met in Montmartre outside Paris, in the crypt of the Chapel of Saint Denis, Rue Yvonne le Tac.

This group bound themselves by a vow of poverty and chastity, to "enter upon hospital and missionary work in Jerusalem, or to go without questioning wherever the pope might direct."

They called themselves the "Company of Jesus," because they felt "they were placed together by Christ." The name had echoes of the military (as in an infantry "company"), as well as of discipleship (the "companions" of Jesus). The modern word "company" comes ultimately from Latin, cum + pane = "bread with," or a group that shares meals.

These initial steps led to the founding of what would be called the Society of Jesus later in 1540. The term societas in Latin is derived from socius, a partner or comrade.

Much is sometimes made of Ignatius' military background; in fact nowhere in the Constitutions of the order is the Society of Jesus compared to an army.

In 1537, they traveled to Italy to seek papal approval for their order. Pope Paul III gave them a commendation, and permitted them to be ordained priests.

They were ordained at Venice by the bishop of Arbe (June 24). They devoted themselves to preaching and charitable work in Italy, as the renewed Italian War of 1535-1538 between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Venice, the pope and the Ottoman Empire rendered any journey to Jerusalem impossible.

They presented the project to the Pope. After months of dispute, a congregation of cardinals reported favorably upon the Constitution presented, and Paul III confirmed the order through the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae ("To the Government of the Church Militant"), on September 27, 1540, but limited the number of its members to 60. This is the founding document of the Jesuits as an official Catholic religious order.

This limitation was removed through the bull Injunctum nobis (March 14, 1543). Ignatius was chosen as the first superior-general. He sent his companions as missionaries around Europe to create schools, colleges, and seminaries.[1]

The Jesuits focused on three activities: First, they founded schools throughout Europe. Jesuit teachers were rigorously trained in both classical studies and theology. The Jesuits' second mission was to convert non-Christians to Catholicism, so they developed and sent out missionaries. Their third goal was to stop Protestantism from spreading. The zeal of the Jesuits overcame the drift toward Protestantism in Poland-Lithuania and southern Germany.

Ignatius wrote the Jesuit Constitutions, adopted in 1554, which created a tightly centralized organization and stressed absolute self-abnegation and obedience to Pope and superiors (perinde ac cadaver, "[well-disciplined] like a corpse" as Ignatius put it).

His main principle became the unofficial Jesuit motto: Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam ("For the greater glory of God"). This phrase is designed to reflect the idea that any work that is not evil can be meritorious for the spiritual life if it is performed with this intention, even things considered normally indifferent.[1]

The Society of Jesus is classified among institutes as a mendicant order of clerks regular, that is, a body of priests organized for apostolic work, following a religious rule, and relying on alms, or donations, for support.

The term "Jesuit" (of fifteenth-century origin, meaning one who used too frequently or appropriated the name of Jesus), was first applied to the Society in reproach (1544-1552), and was never employed by its founder, though members and friends of the Society in time appropriated the name in its positive meaning.

Early works

The Jesuits were founded just before the Counter-Reformation (or at least before the date those historians with a classical view of the counter reformation hold to be the beginning of the Counter-Reformation), a movement whose purpose was to reform the Catholic Church from within and to counter the Protestant Reformers, whose teachings were spreading throughout Catholic Europe.

Ignatius and the early Jesuits did recognize, though, that the hierarchical Church was in dire need of reform, and some of their greatest struggles were against corruption, venality, and spiritual lassitude within the Roman Catholic Church.

Ignatius's insistence on an extremely high level of academic preparation for ministry, for instance, was a deliberate response to the relatively poor education of much of the clergy of his time, and the Jesuit vow against "ambitioning prelacies" was a deliberate effort to prevent greed for money or power invading Jesuit circles.

As a result, in spite of their loyalty, Ignatius and his successors often tangled with the pope and the Roman Curia. Over the 450 years since its founding, the Society has both been called the papal "elite troops" and been forced into suppression.

Saint Ignatius and the Jesuits who followed him believed that the reform of the Church had to begin with the conversion of an individualâs heart. One of the main tools the Jesuits have used to bring about this conversion has been the Ignatian retreat, called the Spiritual Exercises.

During a four-week period of silence, individuals undergo a series of directed meditations on the life of Christ. During this period, they meet regularly with a spiritual director, who helps them understand whatever call or message God has offered in their meditations.

The retreat follows a Purgative-Illuminative-Unitive pattern in the tradition of the mysticism of John Cassian and the Desert Fathers. Ignatius' innovation was to make this style of contemplative mysticism available to all people in active life, and to use it as a means of rebuilding the spiritual life of the Church. The Exercises became both the basis for the training of Jesuits themselves and one of the essential ministries of the order: giving the exercises to others in what became known as "retreats."

The Jesuitsâ contributions to the late Renaissance were significant in their roles both as a missionary order and as the first religious order to operate colleges and universities as a principal and distinct ministry.

By the time of Ignatius' death in 1556, the Jesuits were already operating a network of 74 colleges on three continents. A precursor to liberal education, the Jesuit plan of studies incorporated the Classical teachings of Renaissance humanism into the Scholastic structure of Catholic thought.

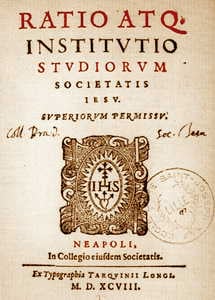

In addition to teaching faith, the Ratio Studiorum emphasized the study of Latin, Greek, classical literature, poetry, and philosophy as well as non-European languages, sciences and the arts. Furthermore, Jesuit schools encouraged the study of vernacular literature and rhetoric, and thereby became important centers for the training of lawyers and public officials.

The Jesuit schools played an important part in winning back to Catholicism a number of European countries which had for a time been predominantly Protestant, notably Poland and Lithuania. Today, Jesuit colleges and universities are located in over one hundred nations around the world.

Under the notion that God can be encountered through created things and especially art, they encouraged the use of ceremony and decoration in Catholic ritual and devotion. Perhaps as a result of this appreciation for art, coupled with their spiritual practice of "finding God in all things," many early Jesuits distinguished themselves in the visual and performing arts as well as in music.

The Jesuits were able to obtain significant influence in the Early Modern Period because Jesuit priests often acted as confessors to Kings of the time. They were an important force in the Counter-Reformation and in the Catholic missions, in part because their relatively loose structure (without the requirements of living in community, saying the divine office together, etc.) allowed them to be flexible to meet the needs of the people at the time.

Expansion

Early missions in Japan resulted in the government granting the Jesuits the feudal fiefdom of Nagasaki in 1580. However, this was removed in 1587 due to fears over their growing influence.

Francis Xavier arrived in Goa, in Western India, in 1541 to consider evangelical service in the Indies. He died in China after a decade of evangelism in Southern India. Two Jesuit missionaries, Johann Gruber and Albert D'Orville, reached Lhasa in Tibet in 1661.

Jesuit missions in Latin America were very controversial in Europe, especially in Spain and Portugal, where they were seen as interfering with the proper colonial enterprises of the royal governments. The Jesuits were often the only force standing between the Native Americans and slavery. Together throughout South America but especially in present-day Brazil and Paraguay they formed Christian Native American city-states, called "reductions" (Spanish Reducciones, Portuguese ReduçÔes). These were societies set up according to an idealized theocratic model. It is partly because the Jesuits protected the natives whom certain Spanish and Portuguese colonizers wanted to enslave that the Society of Jesus was suppressed.

Jesuit priests such as Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta founded several towns in Brazil in the sixteenth century, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and were very influential in the pacification, religious conversion and education of the local peoples.

The Pope had granted exclusive rights to the Society of Jesus to establish missions in Japan, until of the 26 Christians martyred in 1597 under the Taiko, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, three were Jesuits. An expulsion edict followed, leading to Jesuit missionaries relocating to Siam (present day Thailand).

Jesuit scholars working in these foreign missions were linguists, who dedicated their talents to the very important work of translating foreign languages and strived to produce Latinicized grammars and dictionaries. This was done, for instance, for Japanese (see Nippo jisho also known as Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam, (Vocabulary of the Japanese Language) a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary written 1603, and Tupi-Guarani (a language group of South American aborigines). Jean François Pons in the 1740s pioneered the study of Sanskrit in the West.

Under Portuguese royal patronage, the order thrived in Goa and until 1759 successfully expanded its activities to education and healthcare. On 17 December 1759, the Marquis of Pombal, Secretary of State in Portugal, expelled the Jesuits from Portugal and Portuguese possessions overseas.

Jesuit activity in China

The Jesuit China missions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries introduced Western science and astronomy, then undergoing its own revolution, to China. The Society of Jesus introduced, according to Thomas Woods, "a substantial body of scientific knowledge and a vast array of mental tools for understanding the physical universe, including the Euclidean geometry that made planetary motion comprehensible." [2] Additionally:

"[The Jesuits] made efforts to translate western mathematical and astronomical works into Chinese and aroused the interest of Chinese scholars in these sciences. They made very extensive astronomical observation and carried out the first modern cartographic work in China. They also learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture."[3]

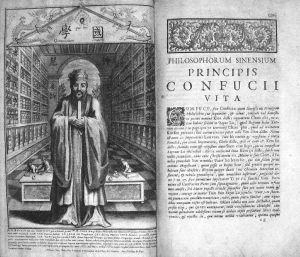

Conversely, the Jesuits were very active in transmitting Chinese knowledge to Europe. Confucius' works were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit scholars stationed in China. Matteo Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta published the life and works of Confucius into Latin in 1687.[4] It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of Confucian morality into Christianity[4][5]. Here are two well-known examples:

- The French physiocrat François Quesnay, founder of modern economics, and a forerunner of Adam Smith was in his lifetime known as "the European Confucius."[4][6] The doctrine and even the name of "Laissez-faire" may have been inspired by the Chinese concept of Wu wei.[7][8]

- Goethe was known as "the Confucius of Weimar".[9]

Suppression and restoration

The Suppression of the Jesuits in Portugal, France, the Two Sicilies, Parma and the Spanish Empire by 1767 was troubling to the Society's defender, Pope Clement XIII. A decree signed under secular pressure by Pope Clement XIV in July 1773 suppressed the Order. The suppression was carried out in all countries except Prussia and Russia, where Catherine the Great had forbidden the papal decree to be executed. Because millions of Catholics (including many Jesuits) lived in the Polish western provinces of the Russian Empire, the Society was able to maintain its existence and carry on its work all through the period of suppression. Subsequently, Pope Pius VI would grant formal permission for the continuation of the Society in Russia and Poland. Based on that permission, Stanislaus Czerniewicz was elected superior of the Society in 1782. Pius VII during his captivity in France, had resolved to restore the Jesuits universally; and after his return to Rome he did so with little delay: on August 7, 1814, by the bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum, he reversed the suppression of the Order and therewith, the then Superior in Russia, Thaddeus Brzozowski, who had been elected in 1805, acquired universal jurisdiction.

The period following the Restoration of the Jesuits in 1814 was marked by tremendous growth, as evidenced by the large number of Jesuit colleges and universities established in the nineteenth century. In the United States, 22 of the Society's 28 universities were founded or taken over by the Jesuits during this time. Some claim that the experience of suppression served to heighten orthodoxy among the Jesuits upon restoration. While this claim is debatable, Jesuits were generally supportive of Papal authority within the Church, and some members were associated with the Ultramontanist movement and the declaration of Papal Infallibility in 1870.

In Switzerland, following the defeat of the Ultramontanist Sonderbund by the other cantons, the constitution was modified and Jesuits were banished in 1848. The ban was lifted on May 20, 1973, when 54.9 percent of voters accepted a referendum modifying the Constitution.[10]

The twentieth century witnessed both aspects of growth and decline. Following a trend within the Catholic priesthood at large, Jesuit numbers peaked in the 1950s and have declined steadily since. Meanwhile the number of Jesuit institutions has grown considerably, due in large part to a late twentieth century focus on the establishment of Jesuit secondary schools in inner-city areas and an increase in lay association with the order. Among the notable Jesuits of the twentieth century, John Courtney Murray, S.J., was called one of the "architects of the Second Vatican Council" and drafted what eventually became the council's endorsement of religious freedom,[11] in apparent contradiction of Pope Eugene IV's Domini Cantate.

Jesuits today

The Jesuits today form the largest religious order of priests and brothers in the Catholic Church, with 19,216 serving in 112 nations on six continents, the largest number being in India followed by those in the United States. The current Superior General of the Jesuits is the Spanish Adolfo NicolĂĄs. The Society is characterized by its ministries in the fields of missionary work, human rights, social justice and, most notably, higher education. It operates colleges and universities in various countries around the world and is particularly active in the Philippines and India. In the United States alone, it maintains over 50 colleges, universities and high schools. A typical conception of the mission of a Jesuit school will often contain such concepts as proposing Christ as the model of human life, the pursuit of excellence in teaching and learning and life-long spiritual and intellectual growth.[12]

In Latin America, liberal Jesuits had significant influence in the development of liberation theology, with a focus on poverty beginning in 1955. A movement based on Marxist ideology, combined with Christian ideals, has been highly controversial in the Catholic theological community and condemned by Pope John Paul II on several fundamental aspects, such as misinterpretation of Holy scripture and following the temptation to reduce the Gospel to an earthly gospel.

Under Superior General Pedro Arrupe, social justice and the "preferential option for the poor" emerged as dominant themes of the work of the Jesuits. On November 16, 1989, six Jesuit priests (Ignacio Ellacuria, Segundo Montes, Ignacio Martin-Baro, Joaquin LĂłpez y LĂłpez, Juan Ramon Moreno, and Amado LĂłpez); their housekeeper, Elba Ramos; and her daughter, Celia Marisela Ramos, were murdered by the Salvadoran military on the campus of the University of Central America in San Salvador, El Salvador, because they had been labeled as subversives by the government. The assassinations galvanized the Society's peace and justice movements.

In 2002, Boston College president William P. Leahy, S.J., initiated the Church in the twenty-first century program as a means of moving the Church "from crisis to renewal." The initiative has provided the Society with a platform for examining issues brought about by the worldwide Roman Catholic sex abuse cases, including the priesthood, celibacy, sexuality, women's roles, and the role of the laity.

On February 2, 2006, Fr. Peter Hans Kolvenbach, informed members of the Society of Jesus, that with the consent of Pope Benedict XVI, he intended to step down as Superior General in 2008, the year he will turn 80. The 35th General Congregation of the Society of Jesus convened on January 5, 2008 and elected Fr. Adolfo NicolĂĄs, a Spanish Jesuit missionary in Japan, as the new Superior General on January 19, 2008. While the Jesuit superior general is elected for life, the order's constitutions allow him to step down.

John Paul II appointed Jesuit priest Roberto Cardinal Tucci, SJ, to the College of Cardinals after serving for many years as the chief organizer of papal trips and public events. In total, John Paul II and Benedict XVI have appointed ten Jesuit cardinals.

Devotion to the Sacred Heart, the Eucharist, and our Lady

The Society of Jesus has a relationship with the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary in a commitment to spread the devotion to the Sacred Heart (though the concept of devotion to Christ's mercy, as symbolized in the image of the Sacred Heart, is more ancient, its modern origins can be traced to Saint Marie Alacoque, a Visitation nun, whose spiritual director was Saint Claude de la ColombiĂšre). The Jesuits particularly promoted this devotion to emphasize the compassion and overwhelming love of Christ for people, and to counteract the rigorism and spiritual pessimism of the Jansenists.

Saint Ignatius counseled souls to receive the Eucharist more often, and from the order's earliest days the Jesuits were promoters of "frequent communion." It should be noted that it was the custom for many Catholics before this time to receive communion perhaps once or twice a year, out of what Catholic theologians considered an exaggerated respect for the sacrament; Ignatius and others advocated communion at least monthly, emphasizing communion not as reward but as spiritual food; by the time of Pope St. Pius X, "frequent communion" had come to mean weekly and even daily reception of the Eucharist.

Ignatius made his initial commitment to a new way of life by leaving his soldier's weapons (and symbolically, his old values) on an altar before an image of the Christ child seated on the lap of Our Lady of Montserrat. The Jesuits were long promoters of the Sodality of Our Lady, their primary organization for their students until the 1960s, which they used to encourage frequent attendance at Mass, reception of communion, daily recitation of the Rosary, and attendance at retreats in the Ignatian tradition of the Spiritual Exercises.

Service and humility

Ignatius emphasized the active expression of God's love in life and the need to be self-forgetful in humility. Part of Jesuit formation is the undertaking of service specifically to the poor and sick in the most humble ways: Ignatius wanted Jesuits in training to serve part of their time as novices and in tertianship (see Formation below) as the equivalent of orderlies in hospitals, for instance, emptying bed pans and washing patients, to learn humility and loving service. Jesuit educational institutions often adopt mottoes and mission statements that include the idea of making students "men for others," and the like. Jesuit missions have generally included medical clinics, schools and agricultural development projects as ways to serve the poor or needy while preaching the Gospel.

Jesuit Formation

The training of Jesuits seeks to prepare men spiritually, academically and practically for the ministries they will be called to offer the Church and world. Saint Ignatius was strongly influenced by the Renaissance and wanted Jesuits to be able to offer whatever ministries were most needed at any given moment, and especially, to be ready to respond to missions (assignments) from the Pope. Formation for Priesthood normally takes up to 14 years, depending on the man's background and previous education, and final vows are taken several years after that, making Jesuit training among the longest of any of the religious orders.

Regardless of the practical details, Jesuit formation is meant to form men who are open and ready to serve whatever is the Churchâs current need. Today, all Jesuits are expected to learn English, and those who speak English as a first language are expected to learn Spanish.

Government of the Society

The Society is headed by a Superior General. In the Jesuit Order, the formal title of the Superior General is "Praepositus Generalis," Latin for "General President," more commonly called "Father General" or "General," who is elected by the General Congregation for life or until he resigns, is confirmed by the Pope, and has absolute authority in running the Society. The current Superior General of the Jesuits is the Spanish Jesuit, Fr. Adolfo NicolĂĄs PachĂłn who was elected on January 19, 2008.

He is aided by "assistants," each of whom heads an "assistancy," which is either a geographic area (for instance, the North American Assistancy) or an area of ministry (for instance, higher education). The assistants normally reside with the General Superior in Rome. The assistants, together with a number of other advisors, form an advisory council to the General. A vicar general and secretary of the Society run day-to-day administration. The General is also required to have an "admonitor," a confidential advisor whose specific job is to warn the General honestly and confidentially when he is acting imprudently or is straying toward disobedience to the Pope or heresy. The central staff of the General is known as the Curia.

The order is divided into geographic provinces, each of which is headed by a Provincial Superior, generally called Father Provincial, chosen by the General. He has authority over all Jesuits and ministries in his area, and is assisted by a socius, who acts as a sort of secretary and chief of staff. With the approval of the General, he appoints a novice master and a master of tertians to oversee formation, and rectors of local houses of Jesuits.

Each individual Jesuit community within a province is normally headed by a rector who is assisted by a "minister," from the Latin for "servant," a priest who helps oversee the community's day-to-day needs.

The General Congregation is a meeting of all of the assistants, provincials and additional representatives who are elected by the professed Jesuits of each province. It meets irregularly and rarely, normally to elect a new superior general and/or to take up some major policy issues for the order. The General meets more regularly with smaller councils composed of just the provincials.

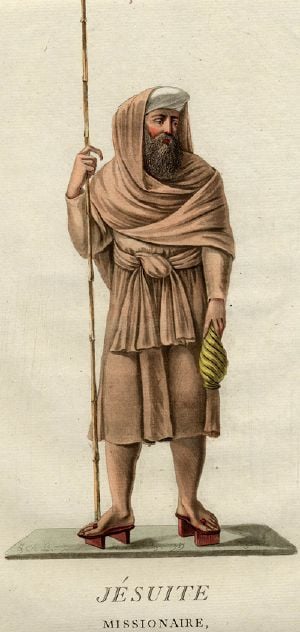

Habit and Dress

Jesuits do not have an official habit. Saint Ignatius' intent was their adoption of diocesan clergy dress in whatever country or region they found themselves. In time, a "Jesuit-style cassock" became standard issue: it wrapped around the body and was tied with a cincture, rather than the customary buttoned front, a tuftless biretta (only diocesan clergy wore tufts), and a simple cape (ferraiuolo) completed the full, formal Jesuit garb, but this too was part of diocesan priestly dress. As such, though their garb appeared distinctive, and became identifiable over time, it was the common priestly dress of Ignatius's day. Missionaries of all religious orders, at their commissioning ceremony, received a large crucifix worn on a cord around the neck that is often tucked, for convenience, to the cassock's cincture: historical depictions of Jesuit saints show the buttonless cassock, cape, biretta, and crucifix.

During the Missionary periods of the Continental Americas, the various Amerindian tribes referred to the Jesuits as the "Blackrobes" because of the black cassocks they wore.

Today, most Jesuits wear the simple Roman collar tab shirts in non-liturgical, ministerial settings. Some, since the 1960s, have opted for secular garb.

Controversies

The Jesuits have frequently been described by their detractors (of both Catholic and Protestant faith) as engaged in various conspiracies. The Monita Secreta, also known as the "Secret Instructions of the Jesuits" was published 1612 and 1614 in KrakĂłw, and is alternately alleged to have been written by either Claudio Acquaviva, the fifth general of the society, or by Jerome Zahorowski. The document appears to lay down the methods to be adopted for the acquisition of greater power and influence for the order and for the Catholic Church. Sympathizers for the Society of Jesus argue that the Secreta were merely fabricated to give the Jesuits a sinister reputation.[13] It is now widely considered to have been a forgery by Zahorowski.

Henry Garnet, one of the leading English Jesuits, was hanged for [treason]] because of his involvement in Gunpowder Plot. The plan had been an attempt to kill King James I of England and VI of Scotland, his family and most of the Protestant aristocracy in a single attack by blowing up the Houses of Parliament in 1605. Another Jesuit, Oswald Tesimond, managed to escape arrest for involvement in the same plot.

Robert Southwell (1561-1595) was another Jesuit was arrested while visiting the house of Richard Bellamy, who lived near Harrow and was under suspicion on account of his connection with Jerome Bellamy, who had been executed for sharing in Anthony Babington's plot. He was hanged for treason.

John Ballard (d. 1586),(also Jesuit), was executed for being involved in an attempt to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I of England. The same fate struck Edmund Campion, a Jesuit priest sentenced to death as a traitor.

Jesuits have also been accused of using casuistry. In English, according to the Concise Oxford Dictionary, "Jesuitical" has acquired a secondary meaning of "equivocating." The Jesuits have also been targeted by many anti-Catholics like Jack Chick, Avro Manhattan, Alberto Rivera (who claimed to be a former Jesuit himself), and the late former Jesuit priest, Malachi Martin.[14]

Jesuits rescue efforts during the Holocaust

Nine Jesuit priests have been formally recognized by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, for risking their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust of World War II. Several other Jesuits are known to have rescued or given refuge to Jews during that period.[15]

A plaque commemorating the 152 Jesuit priests who gave of their lives during the Holocaust was installed at Rockhurst University, a Jesuit university, in Kansas City, Missouri, United States, in April 2007, the first such plaque in the world.

Famous Jesuits

Notable Jesuits include missionaries, educators, scientists, artists and philosophers. Among many distinguished early Jesuits was Saint Francis Xavier, a missionary to Asia who converted more people to Catholicism than anyone before. José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nobrega, founders of the city of São Paulo, Brazil, were also Jesuit priests. Another famous Jesuit was Saint Jean de Brebeuf, a French missionary who was martyred in North America during the 1600s.

Jesuit Educational Institutions

Though there is almost no occupation in civil life, and no ministry within the Church, which a Jesuit has not held at one time or another, and though the work of the Jesuits today embraces a wide variety of apostolates and ministries, they are probably most well known for their educational work.

Since the inception of the order, Jesuits have been teachers. Today, there are Jesuit-run universities, colleges, high schools and middle or elementary schools in dozens of countries. Jesuits also serve on the faculties of both Catholic and secular schools as well.

One of the most prominent of these universities is the Gregorian University in Rome, one of the Church's key seats of learning, associated in a consortium with the Pontifical Biblical Institute and Pontifical Oriental Institute.

In the United States, 28 Jesuit schools are organized as the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities, the oldest one being Georgetown University, founded by Bishop John Carroll in 1789, and the largest Fordham University. The 46 Jesuit high schools are organized as the Jesuit Secondary Education Association. The Jesuits have recently opened a number of middle schools in poor neighborhoods in New York, Boston and Chicago. There are also Jesuits serving on the faculties of other Catholic colleges and universities; additionally they serve on many secular faculties, including those of Harvard, Yale and the University of Virginia.

In Latin America Jesuit institutions are organized into the AsociaciĂłn de Universidades Confiadas a la CompañĂa de JesĂșs en AmĂ©rica Latina (Association of Universities Entrusted to the Jesuits in Latin America).

In the Philippines, the Jesuit universities are all independent, although they maintain institutional ties. The Ateneo de Manila University, Ateneo de Naga University, Xavier University-Ateneo de Cagayan, Ateneo de Zamboanga University, Marian College of Ipil and Ateneo de Davao University are all loosely federated. An affiliated association, Mindanao Consortium of Ateneo Universities, groups all of the Jesuit universities located in Mindanao island with the purpose of promoting Muslim-Christian unity and dialogue as well as to exchange knowledge and expertise in various academic fields.

In Australia, the Jesuits run a number of schools including Xavier College, St Ignatius' College, Riverview, Loyola senior high school [Mt Druitt], Saint Ignatius' College, Athelstone and St Aloysius' College.

In Ireland, the Jesuits run five schools: Belvedere College, Gonzaga College (both in Dublin), Clongowes Wood College in Clane, Co. Kildare, Saint Ignatius College, in Galway city, and Crescent College, which is in Limerick.

In Egypt, the Jesuits are running le College de la Sainte Famille, a private school for boys in Cairo. They are also involved in charity organizations in the South of Egypt.

In Belgium, the Jesuits run various secondary schools (high schools) such as "Sint-Jozefscollege" in Aalst (Dutch-speaking) and "Sint-Jan Berchmans College" in Antwerpen (Dutch-speaking). "Universitair Centrum Sint-Ignatius" in Antwerpen (Dutch-speaking) and the 'Facultés Notre-Dame de la Paix' of Namur (French-speaking) are both Jesuit universities.

In India, the Jesuits run top colleges and schools in the country including Loyola College, Chennai, St. Xavier's College, Mumbai, St. Xavier's College, Calcutta, Xavier Labour Relations Institute, Jamshedpur, Loyola School, Thiruvananthapuram, St Xavier's College, Thiruananthapuram, St Xavier's College, Palayamkottai, Loyola College, Kunkuri, St Xavier's College, Balipara, Xavier Institute of Management, Bhubaneshwar, St Joseph's College, Tiruchirapalli, St Xavier's College, Goa, Andhra Loyola College, Vijaywada, Loyola Academy, Secunderabad, Xavier Institute of Management, Bhubaneswar (XIMB), Xavier Institute of Social Service (XISS) and Xavier Institute of Development and Service (XIDAS), St Vincent's High School, Pune and St Xavier's College, Ranchi, St Xavier's College, Ahmedabad. They also run some of the top theological colleges in India the famous ones being Jnana Deepa Vidyapeeth, Pune (De Nobili College) and Vidyajyoti College of Theology, Delhi. They also run 9 Regional Theology Centers (RTC) for contextual theologies in diverse regions of the country. Their educational institutions also have some of the country's best sportspersons producing centers, prominent among them being St Ignatius High School, Gumla, St Mary's High School, Samtoli, Loyola School Jakhama (Kohima). Some of the top bureaucrats and politicians (including those opposing Christianity) are Jesuit school alumni.

In Hong Kong S.A.R., the Jesuits run two secondary schools including Wah Yan College, Kowloon and Wah Yan College, Hong Kong.

In Japan, the Jesuits founded Sophia University. It is considered to be one of the best private universities in the country, and is one of Tokyo's top ranked private universities.

In Korea, the Jesuits are running Sogang University. It is established in February, 1960. It is founded by Art Dethlefs, Basil Price, Jin Song Man (ì§ì±ë§), Theodor Geppert, Ken Killoren and Clancy Herbst. Nowadays Sogang University is considered to be one of the best private universities in Korea.

In Taiwan, Jesuits founded the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Management of the Catholic Fu-Jen University during the 1950s. In 2003 another new Faculty of Social Sciences was derived from the Faculty of Law. Thus until today, the Fu Jen Catholic University is still considered to be one of the best private universities in Taiwan.

Other Institutions

Jesuits also operate retreat houses, for the purpose of offering the Spiritual Exercises (above) and other types of days of prayer or spiritual programs extended over weekends or weeks. The oldest Jesuit retreat house in the United States is Mount Manresa in Staten Island, New York, and today there are 34 retreat houses or spirituality centers run by the order in the U.S. Jesuits also serve on the staffs of other retreat centers.

Jesuits are also known for their involvement in publications. La CiviltĂ Cattolica, a periodical produced in Rome by the Jesuits, has often been used as a semi-official platform for popes and Vatican officials to float ideas for discussion or hint at future statements or positions. In the United States, America magazine has long had a prominent place in intellectual Catholic circles, and the Jesuits produce Company, a periodical specifically about Jesuit activities. Most Jesuit colleges and universities have their own presses which produce a variety of books, book series, textbooks and academic publications as well. Ignatius Press, staffed by Jesuits, is an independent publisher of Catholic books, most of which are of the popular academic or lay-intellectual variety.

In Australia, the Jesuits run a winery at Sevenhills,[16],the Jesuit Mission Australia, after a few migrated to Australia from Austria in 1848, seeking freedom from persecution. Vineyards were begun in 1851 originally to produce sacramental wine. Jesuits also they produce a number of magazines, including Eureka Street, Madonna, Australian Catholics, and Province Express.

Popular culture

- The Mission 1986 award winning film in which eighteenth century Spanish Jesuits try to protect a remote South American Indian tribe in danger of falling under the rule of pro-slavery Portugal.

- Black Robe a 1991 film about a Jesuit in seventeenth century Quebec and his struggles with the Algonquin tribe.

- The Exorcist A novel and film set at Georgetown University, a Jesuit school, with two Jesuit priests as exorcists for a girl. The novel and screenplay were written by William Peter Blatty, a 1950 graduate of the school, but the story line is based on a true-to-life experience of a young boy in Mount Rainier, Maryland.

- The Sparrow a 1996 science fiction novel by Mary Doria Russell about a Jesuit mission to an alien world.

- James Blish's Hugo Award-winning A Case of Conscience a 1958 science fiction novel about a Jesuit mission to an alien world.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Harro Höpfl, Jesuit political thought: the Society of Jesus and the state, c. 1540-1630. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0521837790), 426.

- â Thomas E. Woods, How The Catholic Church Built Western Civilization (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2005), 101.

- â AgustĂn UdĂas, Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories (Astrophysics and Space Science Library) (Berlin: Springer, ISBN 140201189X).

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 John Parker, Windows into China: the Jesuits and their books. Lecture delivered on the occasion of the fifth annual Bromsen Lecture, April 30, 1977. (Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1978), 25.

- â John M. Hobson, The Eastern origins of Western civilisation. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 194-195.

- â Joseph Dana Miller, Single Tax Year Book (New York: Single Tax Review Publishing Company, 1917), 318.

- â Christian Gerlach, Wu-Wei in Europe. A Study of Eurasian Economic Thought. Working Paper No 12/05 (London: London School of Economics, 2005).

- â John M. Hobson, The Eastern origins of Western civilisation. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 196.

- â Huanyin Yang, "Confucius (Kâung Tzu) (551-479 B.C.E.)" Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education XXIII (1/2)(1993): 211-219. UNESCO. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- â Chancellerie_fĂ©dĂ©rale_(Suisse), "ArrĂȘtĂ© fĂ©dĂ©ral abrogeant les articles de la constitution fĂ©dĂ©rale sur les jĂ©suites et les couvents" (art. 51 et 52) 1973-05-20 (in French). Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- â Dignitatis Humanae Personae Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- â St. Aloysius College mission statement. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- â J. Gerard, "Monita Secreta" Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913. newadvent.org. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- â Malachi Martin, The Jesuits: The Society of Jesus and the Betrayal of the Roman Catholic Church (New York: Simon & Schuster, Linden Press, 1987, ISBN 0671545051),

- â Rev. Vincent A. Lapomarda, S.J., "The Righteous Among the Gentiles: Twelve Jesuit Priests." Hiatt Holocaust Collection. Holy Cross. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- â Sevenhill Retrieved June 24, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barthel, Manfred. Jesuits: History and Legends of the Society of Jesus. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1987. ISBN 978-0688069704

- Campbell, Thomas J. The Jesuits, 1534-1921 V2: A History Of The Society Of Jesus, From Its Foundation To The Present Time. (original 1921 Encyclopedia Press) reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 978-0548769720

- Gerlach, Christian. "Wu-Wei in Europe. A Study of Eurasian Economic Thought." Working Paper No 12/05. London: London School of Economics, 2005.

- Hobson, John M. The Eastern origins of Western civilisation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521547245.

- Höpfl, Harro. Jesuit political thought: the Society of Jesus and the state, c. 1540-1630. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521837790.

- Hughes, Thomas. History Of The Society Of Jesus In North America Colonial And Federal V2: From 1645 Till 1773 Text. (original 1910) reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, LLC., 2006. ISBN 978-1428648708

- Lapomarda, Rev. Vincent A., S.J., "The Righteous Among the Gentiles: Twelve Jesuit Priests." Hiatt Holocaust Collection. Holy Cross.

- Martin, Malachi. The Jesuits: The Society of Jesus and the Betrayal of the Roman Catholic Church. New York: Simon & Schuster, Linden Press, 1987. ISBN 0671545051.

- McCarthy, John L. "The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus and Their Complementary Norms: A Complete English Translation of the Official Latin Texts." Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1996. ISBN 978-1880810248.

- Parker, John. Windows into China: the Jesuits and their books, 1580-1730. delivered on the occasion of the fifth annual Bromsen Lecture, April 30, 1977. Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1978. ASIN B0016CAQ96

- UdĂas, AgustĂn. Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories. (Astrophysics and Space Science Library) Berlin: Springer. ISBN 140201189X.

- Woods, Thomas E. How The Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0895260387

- Yang, Huanyin. "Confucius (Kâung Tzu) (551-479 B.C.E.)," Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education XXIII (No 1/2) 1993.

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2023.

- The Jesuit Portal - Jesuit Worldwide Homepage

- Sacred Space: famous Jesuit prayer site, in 18 different languages, maintained by Jesuits of the Irish Province

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.