John D. Rockefeller

| John Davison Rockefeller | |

| |

| Born | July 8, 1839 Richford, New York U.S.A |

|---|---|

| Died | May 23, 1937 The Casements, Ormond Beach, Florida |

| Occupation | Chairman of Standard Oil Company; investor; philanthropist |

John Davison Rockefeller, Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American industrialist and philanthropist who played a pivotal role in the establishment of the oil industry and defined the structure of modern philanthropy. Rockefeller strongly believed that his purpose in life was to make as much money as possible and then use it wisely to improve the lot of mankind. In 1870, Rockefeller helped found the Standard Oil company. Over a forty-year period, Rockefeller built Standard Oil into the largest and most profitable company in the world, thus becoming the world's richest man.

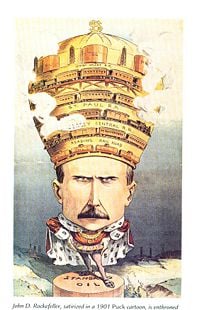

His business career was controversial. He was bitterly attacked by the media of his day, newspapers and the journalists who wrote for them. His company was convicted in Federal Court of monopolistic practices and broken up in the 1911 Standard Oil antitrust settlement. Indicative of its enormous size and influence, four of Standard Oil's successor companies; Exxon (which was known as Esso until 1973), Mobil, Amoco, and Chevron remain among the fifty largest companies in the world.

Rockefeller gave up active management of Standard Oil in the late 1890s, while keeping a large fraction of the shares. He spent the last forty years of his life focused on philanthropy and philanthropic pursuits, primarily related to education and public health. His wealth helped pioneer the development of medical research in North America and was instrumental in the eradication of hookworm and yellow fever. Most of his wealth was donated using multiple foundations run by experts. He was a devout Northern Baptist by religion and supported many church-based institutions throughout his life.

Always avoiding the spotlight, Rockefeller was generous to children and is remembered for handing out nickels or dimes to those he encountered in public. Predeceased by his wife Laura Celestia ("Cettie") Spelman, the Rockefellers had four daughters and one son (John D. Rockefeller, Jr.). Following Rockefeller's retirement from business and later philanthropy, his son was largely entrusted with assuming his duties at Standard Oil and, more significantly, his effort to distribute his wealth for the common good.

Early life

John D. Rockefeller was born on a farm in Tioga County, New York, on July 8, 1839, the son of William A. and Eliza Davison Rockefeller, and the second of six children. When he was a boy, he and his family moved to Moravia and later to Oswego, New York. He moved to Ohio in 1853, where his family bought a home in the town of Strongsville. Young John D. attended Central High School in Cleveland. It was there that he became independent by renting a room and joining the Erie Street Baptist Church, where he later became a church trustee, at the age of 21. [1] In 1855, he left high school to enroll in a business course at Folsom Mercantile College, a six month course, which he completed in three. He later found a job as an assistant bookkeeper for a small firm of commission merchants and produce shippers called Hewitt & Tuttle, later being promoted to cashier and bookkeeper. Later in 1859, he formed a partnership in the commission business with Maurice B. Clark using his savings and money he borrowed from his father. It was in 1859 that the first oil well was drilled in Titusville in western Pennsylvania. A few years later, in 1863, both Clark and Rockefeller entered the petroleum refining industry, along with a partner, Samuel Andrews, who possessed refining experience. Together they founded Andrews, Clark, & Co. Although the business still engaged in commissions, the company was pursuing a new direction. In 1865, the five partners that made up Andrews, Clark, & Co. placed the company up for bids. Rockefeller bought the company for $72,500 and with Andrews formed the company named Rockefeller & Andrews.

Standard Oil

In the early 1870s, Cleveland had become established as one of the five main refining centers in the U.S. (besides Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York, and the region in northwestern Pennsylvania where most of the oil originated), and Standard Oil had established itself as the most profitable refiner in Cleveland. When it was found out that at least part of Standard Oil's cost advantage came from secret rebates from the railroads bringing oil into Cleveland, the competing refiners insisted on getting similar rebates, and the railroads quickly complied. By then, however, Standard Oil had grown to become one of the largest shippers of oil and kerosene in the country.

The railroads were competing fiercely for traffic and, in an attempt to create a cartel to "stabilize" freight rates, formed the South Improvement Company. Rockefeller agreed to support this cartel if they gave him preferential treatment as a high volume shipper, which included not just steep rebates for his product but also rebates for the shipment of competing products. Part of this scheme was the announcement of sharply increased freight charges. This touched off a firestorm of protest, which eventually led to the discovery of Standard Oil's part of the deal. A major New York refiner, Charles Pratt and Company (headed by Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers), led the opposition to this plan, and the railroads abandoned their protests.

Undeterred, Rockefeller continued with his self-reinforcing cycle of buying competing refiners, improving the efficiency of his operations, pressing for discounts on oil shipments, undercutting his competition, and subsequently buying them out. In 1872, Standard Oil had absorbed 22 of its 26 Cleveland competitors in a period of six weeks. Eventually, even his former antagonists Pratt and Rogers saw the futility of continuing to compete against Standard Oil, and in 1874, they made a secret agreement with Standard Oil to be acquired. Pratt and Rogers became Rockefeller's partners. Rogers, in particular, became one of Rockefeller's key men in the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt (1858-1913), became Secretary of Standard Oil.

For many of his competitors, Rockefeller merely had to show them his books so they could see what they were up against and then made them a decent offer. If they refused his offer, he told them he would run them into bankruptcy, then cheaply buy up their assets at auction. Most capitulated.

Monopoly

Standard Oil gradually gained complete control of oil production in America. At that time, many state legislatures had made it difficult to incorporate in one state and operate in another. As a result, Rockefeller and his partners owned separate companies across dozens of states, making their management of the whole enterprise rather unwieldy. In 1882, Rockefeller's lawyers created an innovative form of partnership to centralize their holdings, giving birth to the Standard Oil Trust. The partnership's size and wealth drew much attention. Despite improving the quality and availability of kerosene products while greatly reducing their cost to the public (the price of kerosene dropped by nearly 80 percent over the life of the company), Standard Oil's business practices created intense controversy. The firm was attacked by journalists and politicians throughout its existence, in part for its monopolistic practices, giving momentum to the antitrust movement.

One of the most effective attacks on Rockefeller and his firm was the 1904 publication of The History of the Standard Oil Company by Ida Tarbell. Tarbell was considered a leading muckraker in her day. Although her work prompted a huge backlash against the company, Tarbell claims to have been surprised at its magnitude.

I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form. I was willing that they should combine and grow as big and rich as they could, but only by legitimate means. But they had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me.

It is noted that Tarbell's father had been driven out of the oil business during the South Improvement Company affair.

Ohio was especially vigorous in applying its state antitrust laws and finally forced a separation of Standard Oil of Ohio from the rest of the company in 1892, leading to the dissolution of the trust. Rockefeller continued to consolidate his oil interests until in 1899, New Jersey changed its incorporation laws to effectively allow a re-creation of the trust in the form of a single holding company. At its peak, Standard Oil controlled nearly 90 percent of the market for kerosene products.

By 1896, Rockefeller shed all of his policy involvement in the affairs of Standard Oil. However, he retained his title nominally as president until 1911. He also retained all his Standard Oil stock.

In 1911, the Supreme Court of the United States held that Standard Oil, which by then had a 64 percent market share, originated in illegal monopoly practices and ordered it to be broken up into 34 new companies. These included, among many others: Continental Oil, which became Conoco; Standard of Indiana, which became American Oil Company (and later Amoco); Standard of California, which became Chevron Corporation; Standard of New Jersey, which became Esso (and later, Exxon); Standard of New York, which became Mobil; and Standard of Ohio, which became Sohio. Rockefeller, who had rarely sold shares, owned stock in all of them.

Philanthropy

From his very first paycheck, Rockefeller tithed ten percent of his earnings to his church. As his wealth grew, so did his giving, primarily to educational and public health causes, but also for basic sciences and the arts. He was advised primarily by Frederick T. Gates after 1891 and, after 1897, also by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

Rockefeller believed in the Efficiency Movement, arguing that

To help an inefficient, ill-located, unnecessary school is a waste…it is highly probable that enough money has been squandered on unwise educational projects to have built up a national system of higher education adequate to our needs if the money had been properly directed to that end.[2]

He and his advisers invented the conditional grant that required the recipient to "root the institution in the affections of as many people as possible who, as contributors, become personally concerned, and thereafter may be counted on to give to the institution their watchful interest and cooperation."[3]

In 1884, he provided major funding for a college in Atlanta for black women that became Spelman College (named for Rockefeller's in-laws who were ardent abolitionists before the Civil War). Rockefeller also gave considerable donations to Denison University and other Baptist colleges.

Rockefeller gave $80 million to the University of Chicago under William Rainey Harper, turning a small Baptist College into a world-class institution by 1900. He later called it "the best investment I ever made."[4] His General Education Board, founded in 1902, was established to promote education at all levels everywhere in the country. It was especially active in supporting underprivileged schools in the South. Its most dramatic impact came by funding the recommendations of the Flexner Report of 1910, which had been funded by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; it revolutionized the study of medicine in the United States.

Despite his personal preference for homeopathy, Rockefeller, on Frederick Gates's advice, became one of the first great benefactors of medical science. In 1901, he founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York. It changed its name to Rockefeller University in 1965, after expanding its mission to include graduate education. It claims a connection to 23 Nobel laureates. He founded the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission in 1909, an organization that eventually eradicated the hookworm disease that had long plagued the American South. The Rockefeller Foundation was created in 1913 to continue and expand the scope of the work of the Sanitary Commission, which was closed in 1915. He gave nearly $250 million to the Foundation, which focused on public health, medical training, and the arts. It endowed Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, the first of its kind. The foundation built the Peking Union Medical College into a great institution. It also helped in World War I war relief, 1914-16, and employed William Lyon Mackenzie King of Canada to study industrial relations. Rockefeller's fourth main philanthropy, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation (created in 1918) supported work in the social studies; it was later absorbed into the Rockefeller Foundation. All told, Rockefeller gave away about $550 million.

Oddly enough, Rockefeller was probably best known in his later life for the practice of giving a dime to children wherever he went. He even gave dimes as a playful gesture to men like tire mogul Harvey Firestone and President Herbert Hoover. During the Great Depression, Rockefeller switched to giving nickels instead of dimes.

Legacy

As a youth, Rockefeller allegedly said that his two great ambitions were to make $100,000 and to live 100 years. He died on May 23, 1937, 26 months shy of his 100th birthday, at the Casements, his home in Ormond Beach, Florida. He was buried in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland.

Rockefeller had a long and controversial career in industry followed by a long career in philanthropy. His image is an amalgam of all of these experiences and the many ways he was viewed by his contemporaries. These contemporaries include his former competitors, many of whom were driven to ruin, but many others of whom sold out at a profit (or a profitable stake in Standard Oil, as Rockefeller often offered his shares as payment for a business), and quite a few of whom became very wealthy as managers as well as owners in Standard Oil. They also include politicians and writers, some of whom served Rockefeller's interests and some of whom built their careers by fighting Rockefeller and the "robber barons."

Biographer Allan Nevins, answering Rockefeller's enemies, concluded:

The rise of the Standard Oil men to great wealth was not from poverty. It was not meteor-like, but accomplished over a quarter of a century by courageous venturing in a field so risky that most large capitalists avoided it, by arduous labors, and by more sagacious and farsighted planning than had been applied to any other American industry. The oil fortunes of 1894 were not larger than steel fortunes, banking fortunes, and railroad fortunes made in similar periods. But it is the assertion that the Standard magnates gained their wealth by appropriating "the property of others" that most challenges our attention. We have abundant evidence that Rockefeller's consistent policy was to offer fair terms to competitors and to buy them out, for cash, stock, or both, at fair appraisals; we have the statement of one impartial historian that Rockefeller was decidedly "more humane toward competitors" than Andrew Carnegie; we have the conclusion of another that his wealth was "the least tainted of all the great fortunes of his day.[5]

Biographer Ron Chernow wrote of Rockefeller:

What makes him problematic—and why he continues to inspire ambivalent reactions—is that his good side was every bit as good as his bad side was bad. Seldom has history produced such a contradictory figure.[6]

Notwithstanding these varied aspects of his public life, Rockefeller may ultimately be remembered simply for the raw size of his wealth. In 1902, an audit showed Rockefeller was worth about $200 million—compared to the total national wealth that year of $101 billion. His wealth grew significantly after as the demand for gasoline soared, eventually reaching about $900 million, including significant interests in banking, shipping, mining, railroads, and other industries. By the time of his death in 1937, Rockefeller's remaining fortune, largely tied up in permanent family trusts, was estimated at $1.4 billion. Rockefeller's net worth over the last decades of his life would easily place him among the very wealthiest persons in history. As a percentage of the United States economy, no other American fortune—including Bill Gates or Sam Walton—would even come close.

The Rockefeller wealth, distributed as it was through a system of foundations and trusts, continued to fund family philanthropic, commercial, and, eventually, political aspirations throughout the twentieth century. Grandson David Rockefeller was a leading New York banker, serving for over 20 years as Chief Executive Officer of Chase Manhattan bank (now the retail financial services arm of JP Morgan Chase). Another grandson, Nelson A. Rockefeller, was Republican Governor of New York and the 41st Vice President of the United States. A third grandson, Winthrop Rockefeller, served as Republican Governor of Arkansas. Great-grandson John D. ("Jay") Rockefeller IV was a Democratic Senator from West Virginia.

Rockefeller has passed into popular culture as the embodiment of wealth. Oysters Rockefeller was named for him because the dish was so "rich." The Rockefeller family was a major benefactor in funding the reconstruction effort in France after World War I. As a consequence, Rockefeller (along with the Rothschilds) was considered in that country as the canonical billionaire—synonymous with extreme wealth. John D. Rockerduck is a Disney character popular in Europe who is a foil to another well-known rich duck, the avaricious Scrooge McDuck.

Quotations

- "I had no ambition to make a fortune; mere moneymaking has never been my goal. I had an ambition to build."—John D. Rockefeller.

- "Two men have been supreme in creating the modern world: Rockefeller and Bismarck. One in economics, the other in politics, refuted the liberal dream of universal happiness through individual competition, substituting monopoly and the corporate state, or at least movements toward them"—Bertrand Russell, Freedom Versus Organization, 1814 to 1914, as quoted in Ron Chernow, Titan (1998), preface.

- "The way to make money is to buy when blood is running in the streets."—John D. Rockefeller.

- When asked once, "How much money is enough money?" He replied, "Just a little bit more."

- "Mr. Rockefeller your fortune is rolling up, rolling up like an avalanche! You must keep up with it! You must distribute it faster than it grows! If you do not, it will crush you and your children and your children's children"—Frederick T. Gates in 1906, quoted in the PBS documentary: American Experience, The Rockefellers (Part 1).

- "On one occasion, Rockefeller met in Pittsburgh with a group of refiners. After the meeting, several of the refiners went off to dinner. The talk centered on the taciturn, less than gregarious, menacing man from Cleveland. 'I wonder how old he is,' a refiner said. Various other refiners offered their guesses. 'I've been watching him,' one finally said. 'He lets everybody else talk, while he sits back and says nothing. But he seems to remember everything, and when he does begin he puts everything in its proper place… I guess he's 140 years old—for he must have been 100 years old when he was born'"—Quoted from Daniel Yergin's book, The Prize NY: Simon & Schuster, 1991, p47.

Notes

- ↑ The Rockefeller Archive,p.1 John D Rockefeller. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ↑ Rockefeller, 168

- ↑ Rockefeller p 183

- ↑ The University of Chicago, A Brief History of the University of Chicago. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- ↑ Latham p 104

- ↑ Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. 1998

Bibliography

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. NY: Random House, 1998. ISBN 9780679438083

- Collier, Peter, and David Horowitz. The Rockefellers: An American Dynasty. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976. ISBN 9780030083716

- Folsom, Jr., Burton W. The Myth of the Robber Barons. Herndon, Va. : Young America's Foundation, 1991. ISBN 9780963020307

- Fosdick, Raymond B. The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1952.

- Goulder, Grace. John D. Rockefeller: The Cleveland Years. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1972. ISBN 9780911704099

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988. ISBN 9780684189369

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Conscience: An American Family in Public and in Private. New York: Scribner, 1991. ISBN 9780684193649

- Hawke, David Freeman. John D: The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper and Row, 1980.

- Hidy, Ralph W. and Muriel E. Hidy. Pioneering in Big Business, 1882-1911: History of Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) NY: Harpewr, 1955.

- Jonas, Gerald. The Circuit Riders: Rockefeller Money and the Rise of Modern Science. NY: W.W.Norton and Co, 1989. ISBN 9780393026405

- Josephson, Matthew. The Robber Barons. London: Harcourt, 1962.

- Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. NY: Random House, 1993. ISBN 9780394569758

- Knowlton, Evelyn H. and George S. Gibb. History of Standard Oil Company: Resurgent Years 1911-1927. NY: Harper, 1956.

- Latham, Earl (ed). John D. Rockefeller: Robber Baron or Industrial Statesman? Boston: Heath, 1949.

- Manchester, William. A Rockefeller Family Portrait: From John D. to Nelson. NY: Little, Brown, 1958.

- Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. NY: H. Holt and Co., 2005. ISBN 9780805075991

- Nevins, Allan. Study in Power: John D. Rockefeller, Industrialist and Philanthropist. 2 volumes. NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1953.

- Pyle, Tom, as told to Beth Day. Pocantico: Fifty Years on the Rockefeller Domain. NY: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1964.

- Rockefeller, John D. Random Reminiscences of Men and Events. New York: Sleepy Hollow Press and RAC. (1984) [1909].

- Rose, Kenneth W. and Darwin H. Stapleton. "Toward a "Universal Heritage: Education and the Development of Rockefeller Philanthropy, 1884-1913" Teachers College Record 1992 93(3): 536-555.

- Sampson, Anthony. The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Made. NY: Viking Press, 1975. ISBN 9780670635917

- Stasz, Clarice. The Rockefeller Women: Dynasty of Piety, Privacy, and Service. NY: St. Martins Press, 1995. ISBN 9780312131562

- Tarbell, Ida M. The History of the Standard Oil Company. University of Rochester, 1964.

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991. ISBN 9780671502485

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2025.

- Illustrated article about John D Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company

- Financier's Fortune in Oil Amassed in Industrial Era of 'Rugged Individualism' NY Times Obituary, May 24, 1937.

- A Capital Life A New York Times book review of "Titan" by Ron Chernow (1998).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.