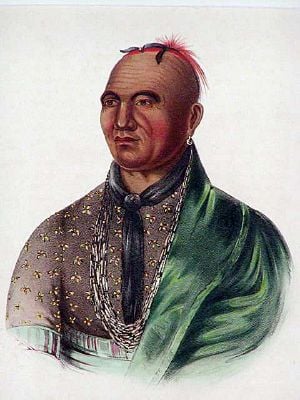

Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (1742 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk leader and British military officer during the American Revolution. Brant was perhaps the most well-known North American Native of his generation, meeting and negotiating with presidents and kings of England, France and the newly formed United States.

Brant's postwar years were spent attempting to rectify the injustice of the Iroquois lands being handed over to the U.S. in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. He acquired lands on behalf of tribes and negotiated for their defense when necessary. His natural ability, his early education, and the connections he was able to form made him one of the great leaders of his people and of his time.

His lifelong mission was to help the Indian to survive the transition from one culture to another, transcending the political, social and economic challenges of one the most volatile, dynamic periods of American history.

Personal life

Joseph Brant was born in 1742 on the banks of the Cuyahoga River, near the present-day city of Akron, Ohio. His birth occurred during the seasonal hunting trip when the Mohawks traveled to the area. The Mohawks' traditional homeland, where Brant grew up, is in what is now upstate New York.

He was named Thayendanegea, which means "two sticks of wood bound together for strength." He was a Mohawk of the Wolf Clan (his mother's clan). Fort Hunter church records indicate that his parents were Christians and their names were Peter and Margaret (Owandah) Tehonwaghkwangearahkwa[1]. It is reported that Peter died before his son Joseph reached the age of ten.

The Mohawk nation was matrilineal and matrilocal. Though his mother was a Caughnawaga sachem (or tribal leader), the succession would not pass to Joseph, but to his older sister, Molly. Joseph's leadership would be as what was known as a "pine tree chief", meaning his political power would rest on recognition of white political or military leaders, rather than from within his own tribe.[2]

Upon the death of her first husband, Joseph's mother took him and his older sister Mary (known as Molly) to the village of Canajoharie, on the Mohawk River in east-central New York. She remarried on September 9, 1753 in Fort Hunter, a widower named Brant Canagaraduncka, who was a Mohawk sachem. Her new husband's grandfather was Sagayendwarahton, or "Old Smoke," who visited England in 1710.

The marriage bettered Margaret's fortunes and the family lived in the best house in Canajoharie, but it conferred little status on her children, as Mohawk titles descended through the female line. However, Brant's stepfather was also a friend of William Johnson, who was to become General Sir William Johnson, Superintendent for Northern Indian Affairs. During Johnson's frequent visits to the Mohawks he always stayed at the Brant's home. Johnson married Joseph’s sister, Molly.

Starting at about age 15, Brant took part in a number of French and Indian War expeditions, including James Abercrombie’s 1758 invasion of Canada via Lake George, William Johnson's 1759 Battle of Fort Niagara, and Jeffery Amherst's 1760 siege of Montreal via the Saint Lawrence River. He was one of 182 Indians who received a silver medal for good conduct.

In 1761, Johnson arranged for three Mohawks including Joseph to be educated at Moor's Indian Charity School in Connecticut, the forerunner of Dartmouth College, where he studied under the guidance of the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock. Wheelock wrote Brant was "of a sprightly genius, a manly and gentle deportment, and of a modest, courteous and benevolent temper." At the school, Brant learned to speak, read, and write English, and became acquainted with Samuel Kirkland. Brant was also baptized during this time. In 1763, Johnson prepared to place Brant at King's College in New York City, but the outbreak of Pontiac's Rebellion upset these plans and Brant returned home. After Pontiac's rebellion Johnson thought it was not safe for Brant to return to the school.

In March 1764, Brant participated in one of the Iroquois war parties that attacked Delaware Indian villages in the Susquehanna and Chemung valleys. They destroyed three good-sized towns and burned 130 houses and killed their cattle. No enemy warriors were reported to have been seen.[1]

On July 22, 1765, Joseph Brant married Peggie (also known as Margaret) in Canajoharie. Peggie was a white captive sent back from western Indians and said to be the daughter of a Virginia gentleman.[1] They moved into Brant's parent's house and when his stepfather died in the mid-1760s the house became Joseph's. He owned a large and fertile farm of 80 acres near the village of Canajoharie on the south shore of the Mohawk River. He raised corn, kept cattle, sheep, horses, and hogs. He also kept a small store. Brant dressed in "the English mode" wearing "a suit of blue broad cloth." With Johnson's encouragement the Mohawk's made Brant a war chief and their primary spokesman. In March, 1771 his wife died from tuberculosis.

In the spring of 1772, he moved to Fort Hunter to live with the Reverend John Stuart. He became Stuart's interpreter, teacher of Mohawk, and collaborated with him in translating the Anglican catechism and the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language. Brant became a lifelong Anglican.

In 1773, Brant moved back to Canajoharie and married Peggie's half-sister, Susanna. Within a year, his second wife also fell victim to tuberculosis.[2]He later married Catherine Croghan, the daughter of the prominent American colonist and Indian agent, George Croghan and a Mohawk mother, Catharine Tekarihoga. Through her mother, Catharine Adonwentishon was head of the Turtle clan, the first in rank in the Mohawk Nation.

Brant fathered nine children, two by his first wife Christine - Isaac and Christine - and seven with his third wife, Catherine - Joseph, Jacob, John, Margaret, Catherine, Mary and Elizabeth.

American Revolution

Brant spoke at least three and possibly all of the Six Nations languages. He was a translator for the Department of Indian Affairs since at least 1766 and in 1775, and was appointed as departmental secretary with the rank of Captain for the new British Superintendent for Northern Indian affairs, Guy Johnson. In May, 1775 he fled the Mohawk Valley with Johnson and most of the Native warriors from Canajoharie to Canada, arriving in Montreal on July 17. His wife and children went to Onoquaga, a large Iroquois village, located on both sides of the Susquehanna River near present-day Windsor, New York.

On November 11, 1775, Guy Johnson took Brant along with him when he traveled to London. Brant hoped to get the Crown to address past Mohawk land grievances, and the government promised the Iroquois people land in Canada if he and the Iroquois Nations would fight on the British side. In London, Brant became a celebrity, and was interviewed for publication by James Boswell. While in public he carefully dressed in the Indian style. He also became a Mason, and received his apron personally from King George III.

Brant returned to Staten Island, New York in July 1776 and immediately became involved with Howe's forces as they prepared to retake New York. Although the details of his service that summer and fall were not officially recorded, he was said to have distinguished himself for bravery, and it has been deduced that he was with Clinton, Cornwallis, and Percy in the flanking movement at Jamaica Pass in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776.[1]It was at this time that he embarked on a lifelong relationship with Lord Percy, later Duke of Northumberland, the only lasting friendship he shared with a white man.

In November, Brant left New York City traveling northwest through American-held territory. Disguised, traveling at night and sleeping during the day, he reached Onoquaga where he joined his family. At the end of December he was at Fort Niagara. He traveled from village to village in the confederacy urging the Iroquois to abandon neutrality and to enter the war on the side of the British. The Iroquois balked at Brant's plans because the full council of the Six Nations had previously decided on a policy of neutrality and had signed a treaty of neutrality at Albany in 1775. They also considered Brant to be simply a minor war chief from a relatively weak people, the Mohawks. Frustrated, Brant freelanced by heading in the spring to Onoquaga to conduct war his way. Few Onoquaga villagers joined him, but in May he was successful in recruiting Loyalists who wished to strike back. This group became known as Brant's Volunteers. In June, he led them to Unadilla village to obtain supplies. At Unadilla, he was confronted by 380 men of the Tryon County militia led by Nicholas Herkimer. Herkimer requested that the Iroquois remain neutral while Brant maintained that the Indians owed their loyalty to the King.

Brant's sister Molly also lobbied for a strong contingent of warriors to join the British forces. Finally, in July 1777, the Six Nations Council, with the exception of a large faction of Oneidas, decided to abandon neutrality and to enter the war on the British side.

For the remainder of the war, Joseph Brant was involved extensively in military operations in the Mohawk valley. In August 1777, Brant played a major role at the Battle of Oriskany in support of a major offensive led by General John Burgoyne. In May of 1778, he led an attack on Cobleskill, and in September, along with Captain William Caldwell, he led a mixed force of Indians and Loyalists in a raid on German Flatts.

In October, 1778, Continental soldiers and local militia attacked Brant's base of Onoquaga while Brant's Volunteers were away on a raid. The American commander described Onoquaga as "the finest Indian town I ever saw; on both sides [of] the river there was about 40 good houses, square logs, shingles & stone chimneys, good floors, glass windows." The soldiers burned the houses, killed the cattle, chopped down the apple trees, spoiled the growing corn crop, and killed some native children they found in the corn fields. On November 11, 1778, in retaliation, Brant led the attack known as the Cherry Valley massacre.

In February, 1779, he traveled to Montreal to meet with Frederick Haldimand who had replaced Carleton as Commander and Governor in Canada. Haldimand gave Brant a commission of 'Captain of the Northern Confederated Indians'. He also promised provisions, but no pay, for his Volunteers. Haldimand also pledged that after the war had ended the Mohawks would be restored, at the expense of the government, to the state they were before the conflict started.

The following May, Brant returned to Fort Niagara where he acquired a farm on the Niagara River, six miles from the fort. He built a small chapel for the Indians who began settling nearby.

In early July, 1779, the British learned of plans for a major American expedition into Seneca country. In an attempt to disrupt the Americans' plans John Butler sent Brant and his Volunteers on a quest for provisions and to gather intelligence on the Delaware in the vicinity of Minisink. After stopping at Onaquaga Brant attacked and defeated the Americans at the Battle of Minisink on July 22, 1779. However, Brant's raid failed to disrupt the American expedition.

A large American force, known as the Sullivan Campaign, entered deep into Iroquois territory to defeat them and destroy their villages. The Iroquois were defeated on August 29, 1779 at the Battle of Newtown. The Americans swept away all Indian resistance in New York, burned their villages, and forced the Iroquois to fall back to Fort Niagara (where Brant was wintering at the time). Red Jacket, a Seneca chief long opposed to Brant for his ties to the British, blamed Brant's policies for the revenge of the Clinton-Sullivan patriots.

In April 1781 Brant was sent west to Fort Detroit in order to help defend against an expedition into the Ohio Country to be led by the Virginian George Rogers Clark. That August, Brant completely defeated a detachment of Clark's army, ending the threat to Detroit. He was wounded in the leg and spent the winter of 1781-1782 at Fort Detroit. From 1781 to 1782, he attempted to keep the disaffected western tribes loyal to the Crown before and after the British surrender at Yorktown.

In the Treaty of Paris (1783) that ended the war, Britain and the United States ignored the sovereignty of the Indians, and sovereign Six Nation lands were claimed by the United States. Promises of protection of their domain had been an important factor in inducing the Iroquois to fight on the side of the British. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784) served as a peace treaty between the Americans and the Iroquois.

Brant's reputation

Although Brant had not been present at the battle of the Wyoming Valley massacre, rumor was that he led it. During the war, he had become known as the Monster Brant, and stories of his massacres and atrocities added to a hatred of Indians that soured relations for 50 years.

In later years historians have argued that he actually had been a force for restraint in the violence that characterized many of the actions in which he was involved; they have discovered times when he displayed his compassion and humanity, especially towards women, children, and non-combatants. Colonel Ichabod Alden said that he "should much rather fall into the hands of Brant than either of them [Loyalists and Tories]".[1]

His compassion was experienced by Lt. Col. William Stacy of the Continental Army, the highest ranking officer captured during the Cherry Valley massacre. Several accounts indicate that during the fighting, or shortly thereafter, Col. Stacy was stripped naked, tied to a stake, and was about to be tortured and killed, but was spared by Brant. Stacy, like Brant, was a Freemason. It is reported that Stacy made an appeal as one Freemason to another, and Brant intervened.[3][4][5][6]

Post-war efforts

Brant spent much of his time after the war attempting to rectify the injustice of the Iroquois lands being taken over by the new nation of the United States. He acquired lands on behalf of tribes and negotiated for their defense when necessary.

In 1783, at Brant's urging, British General Sir Frederick Haldimand made a grant of land for a Mohawk reserve on the Grand River in Ontario in October, 1784. In the fall of 1784, at a meeting at Buffalo Creek, the clan matrons decided that the Six Nations should divide with half going to the Haldimand grant and the other half staying in New York. Brant built his own house at Brant's Town which was described as "a handsome two story house, built after the manner of the white people. Compared with the other houses, it may be called a palace." He had a good farm and did extensive farming, and kept cattle, sheep, and hogs.

In the summer of 1783, Brant initiated the formation of the Western Confederacy consisting of the Iroquois and 29 other Indian nations to defend the Fort Stanwix Treaty line of 1768 by denying any nation the ability to cede any land without the common consent. In November, 1785 he traveled to London to ask for assistance in defending the Indian confederacy from attack by the Americans. Brant was granted a generous pension and an agreement to fully compensate the Mohawk for their losses, but no promises of support for the Western Confederacy. He also took a trip to Paris, returning to Canada in June, 1786.

In 1790, after the Western Confederacy had been attacked in the Northwest Indian War, they asked Brant and the Six Nations to enter the war on their side. Brant refused, he instead asked Lord Dorchester for British assistance for the Western Confederacy. Dorchester also refused, but later, in 1794, did provide the Indians with arms and provisions. In 1792, Brant was invited to Philadelphia where he met the President and his cabinet. The Americans offered him a large pension, and a reservation in the United States for the Canadian Mohawks; Brant refused. Brant attempted a compromise peace settlement between the Western Confederacy and the Americans, but he failed. The war continued, and the Indians were defeated in 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The unity of the Western Confederacy was broken with the peace Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

In early 1797, Brant traveled to Philadelphia where he met the British Minister, Robert Liston and United States government officials. He assured the Americans that he "would never again take up the tomahawk against the United States." At this time the British were at war with France and Spain, and while Brant was meeting with the French minister, Pierre August Adet, he stated he would "offer his services to the French Minister Adet, and march his Mohawks to assist in effecting a revolution & overturning the British government in the province".[7] When he returned home, there were fears of a French attack. Russell wrote: "the present alarming aspect of affairs - when we are threatened with an invasion by the French and Spaniards from the Mississippi, and the information we have received of emissaries being dispersed among the Indian tribes to incite them to take up the hatchet against the King's subjects." He also wrote Brant "only seeks a feasible excuse for joining the French, should they invade this province." London ordered Russell to not allow the Indians to alienate their land, but with the prospects of war to appease Brant, Russell confirmed Brant's land sales. Brant then declared: "they would now all fight for the King to the last drop of their blood."

In late 1800 and early 1801 Brant wrote to Governor George Clinton to secure a large tract of land near Sandusky which could serve as a refuge should the Grand River Indians rebel, but suffer defeat. In September, 1801 Brant is reported as saying: "He says he will go away, yet the Grand River Lands will [still] be in his hands, that no man shall meddle with it amongst us. He says the British Government shall not get it, but the Americans shall and will have it, the Grand River Lands, because the war is very close to break out."[7] In January, 1802, the Executive Council of Upper Canada learned of this plot which was lead by Aaron Burr and George Clinton to overthrow British rule in cooperation with some inhabitants and to create a republican state to join the United States. September, 1802, the planned date of invasion, passed uneventfully and the plot evaporated.

Brant bought about 3,500 acres from the Mississauga Indians at the head of Burlington Bay. Simcoe would not allow such a sale between Indians, so he bought this track of land from the Mississauga and then gave the land to Brant. Around 1802, Brant moved there and built a mansion that was intended to be a half-scale version of Johnson Hall. He had a prosperous farm in the colonial style with 100 acres of crops.

Death

Joseph Brant died in his house at the head of Lake Ontario, at the site of what would become the city of Burlington, on November 24, 1807. His last words, spoken to his adopted nephew John Norton, reflect his life-long commitment to his people:

"Have pity on the poor Indians. If you have any influence with the great, endeavor to use it for their good."

In 1850, his remains were carried 34 miles in relays on the shoulders of young men of Grand River to a tomb at Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford.

Legacy

Brant acted as a tireless negotiator for the Six Nations to control their land without crown oversight or control. He used British fears of his dealings with the Americans and the French to extract concessions. His conflicts with British administrators in Canada regarding tribal land claims were exacerbated by his relations with the American leaders.

Brant was a war chief, and not a hereditary Mohawk sachem. His decisions could and were sometimes overruled by the sachems and clan matrons. However, his natural ability, his early education, and the connections he was able to form made him one of the great leaders of his people and of his time. The situation of the Six Nations on the Grand River was better than that of the Iroquois who remained in New York. His lifelong mission was to help the Indian to survive the transition from one culture to another, transcending the political, social and economic challenges of one the most volatile, dynamic periods of American history. He put his loyalty to the Six Nations before loyalty to the British. His life cannot be summed up in terms of success or failure, although he had known both. More than anything, Brant's life was marked by frustration and struggle.

His attempt to create pan-tribal unity proved unsuccessful, though his efforts would be taken up a generation later by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh.

During his lifetime, Brant was the subject of many portrait artists. Two in particular signify his place in American, Canadian, and British history. George Romney's portrait, painted during the first trip to England in 1775-1776, hangs in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. The Charles Willson Peale portrait was painted during his visit to Philadelphia in 1797, and hangs in Independence Hall. Brant always changed from his regular clothes to dress in Indian fashion for the portraits.

Brant's house in Burlington was demolished in 1932. The present Joseph Brant Museum was constructed on land Brant once owned.

- The City of Brantford the County of Brant, Ontario, located on part of his land grant, is named for him as is, the Erie County Town of Brant.

- Joseph Brant Memorial Hospital in Burlington is named for Brant, and stands on land he had owned.

- A statue of Brant, located in Victoria Square, Brantford, was dedicated in 1886.

- The township of Tyendinaga and the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory Indian reserve are named for Brant, taking their name from an alternate spelling of his traditional Mohawk name.

- The neighborhood of Tyandaga in Burlington is similarly named, using a simplified spelling of his Mohawk name.

- Thayendanegea is one of the 14 leading Canadian military figures commemorated at the Valiants Memorial in Ottawa.

Notable descendants

- Lieutenant Cameron D. Brant, was the first of 30 members of the Six Nations, as well as the first Native North American, to die in World War II. He was killed in the 2nd Battle of Ypres on April 23, 1915 after leading his men "over the top."[8]

- Another Joseph Brant descendant (4th great-grandson), Terence M. Walton, was the youngest veteran of the Korean War era, having enlisted in the U.S. Army at age 14.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Isabel Thompson Kelsey. 1986. Joseph Brant, 1743-1807, man of two worlds. An Iroquois book. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Harvey Markowitz, and Carole A. Barrett. 2005. American Indian biographies. Magill's choice. (Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. ISBN 9781587652332)

- ↑ Joseph Barker, and George Jordan Blazier. 1958. Joseph Barker: recollections of the first settlement of Ohio. (Marietta, Ohio: [s.n.].)

- ↑ John May, Richard Sullivan Edes, and William M. Darlington. 1873. Journal and letters of Col. John May, of Boston: relative to two journeys to the Ohio country in 1788 and '89. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co. for the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio)

- ↑ Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, and Francis S. Drake. 1873. Memorials of the Society of the Cincinnati of Massachusetts. (Boston: Printed for the Society.)

- ↑ Levi Beardsley. 1852. Reminiscences: personal and other incidents; early settlement of Otsego County; notices and anecdotes of public men; judicial, legal, and legislative matters; field sports; dissertations and discussions. (New-York: Printed by Charles Vinten.)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Alan Taylor. 2006. The divided ground: Indians, settlers and the northern borderland of the American Revolution. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0679454713)

- ↑ Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Memorial record, Cameron Donald Brant. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barker, Joseph, and George Jordan Blazier. 1958. Joseph Barker: recollections of the first settlement of Ohio. Marietta, Ohio: [s.n.].

- Beardsley, Levi. 1852. Reminiscences: personal and other incidents ; early settlement of Otsego County; notices and anecdotes of public men; judicial, legal, and legislative matters; field sports; dissertations and discussions. New-York: Printed by Charles Vinten.

- Cassar, George H. 1985. Beyond courage: the Canadians at the Second Battle of Ypres. [Ottawa, Ont.]: Oberon Press. ISBN 9780887506000

- Chalmers, Harvey. 1955. Joseph Brant: Mohawk. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Edmunds, R. David. 1980. American Indian leaders: studies in diversity. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 21-40. ISBN 0803267053

- Garraty, John A., and Mark C. Carnes. 1999. American national biography. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195206355

- Graymont, Barbara. 1972. The Iroquois in the American Revolution. A New York State study. [Syracuse, NY]: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815600836

- Graymont, Barbara. 2000. Joseph Brant. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- Johnson, Michael. 2003. Tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1841764906

- Kelsay, Isabel Thompson. 1986. Joseph Brant, 1743-1807, man of two worlds. An Iroquois book. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815602088

- Markowitz, Harvey, and Carole A. Barrett. 2005. American Indian biographies. Magill's choice. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. ISBN 9781587652332

- Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, and Francis S. Drake. 1873. Memorials of the Society of the Cincinnati of Massachusetts. Boston: Printed for the Society. 465–467.

- May, John, Richard Sullivan Edes, and William M. Darlington. 1873. Journal and letters of Col. John May, of Boston: relative to two journeys to the Ohio country in 1788 and '89. Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co. for the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio. 70–71.

- Merrell, James Hart. 2000. Into the American woods: negotiators on the Pennsylvania frontier. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393319767

- Nash, Gary B. 2005. The Unknown American Revolution: the unruly birth of democracy and the struggle to create America. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780670034208

- Prevost, Toni Jollay. 1995. Indians from New York in Ontario and Quebec, Canada: a genealogy reference. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books. ISBN 0788402579

- Stone, William L. 1838. Life of Joseph Brant (Thayendenegea) including the border wars of the American revolution, and sketches of the Indian campaigns of Generals Harmar, St. Clair, and Wayne, and other matters connected with the Indian relations of the United States and Great Britain, from the peace of 1783 to the Indian peace of 1795. Buffalo, NY: Phinney & co.

- Taylor, Alan. 2006. The divided ground: Indians, settlers and the northern borderland of the American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0679454713

- United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada. 1991. Loyalist families of the Grand River Branch, United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada. Toronto, Canada: Pro Familia Pub. ISBN 0969251459

- Volwiler, Albert T., and George Croghan. 2000. George Croghan and the westward movement, 1741-1782. The Great Pennsylvania frontier series. Lewisburg, PA: Wennawoods Pub. ISBN 9781889037226

- Watt, Gavin K. 2002. Rebellion in the Mohawk Valley: the St. Leger expedition of 1777. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 9781550023763

- Williams, Glenn F. 2005. Year of the hangman: George Washington's campaign against the Iroquois. Yardley, PA: Westholme. ISBN 1594160139

External links

All links retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), Mohawk.indigenouspeople.net.

- Joseph Brant: The Demise of the Iroquois League.crookedlakereview.

- Dictionay of Canadian Biography Online. Thayendanegea bilingual, French and English.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.