Kushan Empire

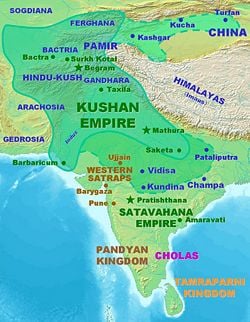

Kushan territories (full line) and maximum extent of Kushan dominions under Kanishka (dotted line), according to the Rabatak inscription.[1] | |

| Languages | Bactrian Greek Pali Sanskrit, Prakrit Possibly Aramaic |

|---|---|

| Religions | Central Asian Cults Zoroastrianism Buddhism Ancient Greek religion Hinduism |

| Capitals | Begram Taxila Mathura |

| Area | Central Asia Northwestern Indian subcontinent |

| Existed | 60 – 375 C.E. |

The Kushan Empire (c. First–Third Centuries) reached its cultural zenith circa 105 – 250 C.E., extended from Tajikistan to Afghanistan, Pakistan and into the Ganges River valley in northern India. The Kushan tribe of the Yuezhi confederation, believed to be Indo-European people from the eastern Tarim Basin, China, possibly related to the Tocharians, created the empire. They were the furthest eastern Indo-European speaking people.

The Kushans adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria, adapting a form of the Greek alphabet into their own language. They practiced Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and possibly Saivism, while taking elements of the Indian culture which them mingled with Hellenistic culture. The empire attained great wealth by uniting sea trade on the Indian Ocean with the overland trade on the Silk Road.

Much is known of the Kushan religious life. Their pantheon of deities have been revealed by the images and inscriptions on coins. Those deities have their origin in Greek, Iranian and, to a lesser degree, Indian religions. The Kushans developed Greco-Buddhism by fusing Hellenistic and Buddhist religious symbols and beliefs, thus creating a form of Mahayana Buddhism. King Kanishka I (127–c.147), who had Prakrit Buddhist texts translated into Sanskrit, convened one of the great Buddhist councils in Kashmir. Kanishka I achieved stature equal to Ashoka 304 B.C.E. – 232 B.C.E.) as emperors advancing Buddhism. The Kushans also promoted Hinayana and Mahayana scriptures in China, playing a key role in the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.

The reign of Vasudeva I (d. 225) marked the last great king of the Kushan Empire. Upon his death the empire split into western and eastern segments leading to a series of defeats of Western Kushan Empire by the Persian Sassanid Empire. The Gupta Empire subjugated the Eastern Kushan Empire in the mid fourth century C.E. A new dynasty, the Kidarites, succeeded in the eastern empire, and then suffered complete annihilation. Both the White Huns in the fifth century and the expansion of Islam throughout the region erased the Kidarite influence. Thus ended a mighty empire that had bridged the East and the West for nearly three centuries. The Kushan Empire had diplomatic contacts with Rome, Persia, and China and for several centuries stood at the center of exchange between the East and the West.

Origins

Chinese sources describe the Guishuang (Ch: 貴霜), i.e. the "Kushans," as one of the five aristocratic tribes of the Yuezhi, also spelled Yueh-chi,[2] (Ch: 月氏), a loose confederation of supposedly Indo-European peoples.[3] The Yuezhi are also generally considered as the easternmost speakers of Indo-European languages, who had been living in the arid grasslands of eastern Central Asia, in modern-day Xinjiang and Gansu, possibly speaking versions of the Tocharian language, until they were driven west by the Xiongnu in 176–160 B.C.E. The five tribes constituting the Yuezhi are known in Chinese history as Xiūmì (Ch: 休密), Guishuang (Ch: 貴霜), Shuangmi (Ch: 雙靡), Xidun (Ch: 肸頓), and Dūmì (Ch: 都密).

Historian John Keay contextualizes the movements of the Kushan within a larger setting of mass migrations taking place in the region:

Chinese sources tell of the construction of the Great Wall in the third century B.C.E. and the repulse of various marauding tribes. Forced to head west and eventually south, these tribes displaced others in an ethnic knock-on effect which lasted many decades and spread right across Central Asia. The Parthians from Iran and the Bactrian Greeks from Bactria had both been dislodged by the Shakas coming down from somewhere near the Aral Sea. But the Shakas had in turn been dislodged by the Yueh-chi who had themselves been driven west to Xinjiang by the Hiung-nu. The last, otherwise the Huns, would happily not reach India for a long time. But the Yueh-chi continued to press on the Shakas, and having forced them out of Bactria, it was sections or clans of these Yueh-chi who next began to move down into India in the second half of the first century AD."[4]

The Yuezhi reached the Hellenic kingdom of Greco-Bactria, in the Bactrian territory (northernmost Afghanistan and Uzbekistan) around 135 B.C.E. The displaced Greek dynasties resettled to the southeast in areas of the Hindu Kush and the Indus basin (in present day Pakistan), occupying the western part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

Early Kushans

Some traces remain of the presence of the Kushan in the area of Bactria and Sogdiana. Archaeological structures known in Takht-I-Sangin, Surkh Kotal (a monumental temple), and in the palace of Khalchayan remain. Various sculptures and friezes, representing horse-riding archers[5], and significantly men with artificially deformed skulls, such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan[6] (a practice well attested in nomadic Central Asia) have been discovered. On the ruins of ancient Hellenistic cities such as Ai-Khanoum, archaeologists believe the Kushans built fortresses. King Heraios (1-30 C.E.) had been the earliest documented ruler, and the first one to proclaim himself as a Kushan ruler. He calls himself a "Tyrant" on his coins, and also exhibits skull deformation. He may have been an ally of the Greeks, and he shared the same style of coinage. Heraios may have been the father of the first Kushan emperor Kujula Kadphises.

A multi-cultural Empire

In the following century, the Guishuang (Ch: 貴霜) gained prominence over the other Yuezhi tribes, and welded them into a tight confederation under yabgu (Commander) Kujula Kadphises. The name Guishuang was adopted in the West and modified into Kushan to designate the confederation, although the Chinese continued to call them Yuezhi.

Gradually wresting control of the area from the Scythian tribes, the Kushans expanded south into the region traditionally known as Gandhara, an area lying primarily in Pakistan's Pothowar, and Northwest Frontier Provinces region but going in an arc to include Kabul valley and part of Qandahar in Afghanistan, and established twin capitals near present-day Kabul and Peshawar then known as Kapisa and Pushklavati respectively.

The Kushans adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria. They adapted the Greek alphabet, often corrupted, to suit their own language, using the additional development of the letter Þ "sh," as in "Kushan," and soon began minting coinage on the Greek model. On their coins they used Greek language legends combined with Pali legends (in the Kharoshthi script), until the first few years of the reign of Kanishka. After that date, they used Kushan language legends (in an adapted Greek script), combined with legends in Greek (Greek script) and legends in Pali (Kharoshthi script).

The Kushans had been predominantly Zoroastrian and later Buddhist. From the time of Wima Takto, many Kushans started adopting aspects of Indian culture like the other nomadic groups who had invaded India, principally the Royal clans of Gujjars. Like the Egyptians, they absorbed the strong remnants of the Greek Culture of the Hellenistic Kingdoms, becoming at least partly Hellenized. The first great Kushan emperor Wima Kadphises (r. ca. 90-100 C.E.) may have embraced Saivism, as surmised by coins minted during the period. The Kushan emperors who followed represented a wide variety of faiths including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and possibly Saivism.

The rule of the Kushans linked the seagoing trade of the Indian Ocean with the commerce of the Silk Road through the long-civilized Indus Valley. At the height of the dynasty, the Kushans loosely oversaw a territory that extended to the Aral Sea through present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan into northern India. The loose unity and comparative peace of such a vast expanse encouraged long-distance trade, brought Chinese silks to Rome, and created strings of flourishing urban centers.

Territorial expansion

Archaeological evidence of a Kushan rule of long duration in an area stretching from Surkh Kotal, Begram, the summer capital of the Kushans, Peshawar the capital under Kanishka I, Taxila and Mathura, the winter capital of the Kushans has been discovered. Other areas of rule may include Khwarezm (Russian archaeological findings) Kausambi (excavations of the Allahabad University), Sanchi and Sarnath (inscriptions with names and dates of Kushan kings), Malwa and Maharashtra, Orissa (imitation of Kushan coins, and large Kushan hoards).[7]

The recently discovered Rabatak inscription tends to confirm large Kushan dominions in the heartland of India. The lines 4 to 7 of the inscription[8] describe six identifiable cities under the rule of Kanishka: Ujjain, Kundina, Saketa, Kausambi, Pataliputra, and Champa (although the obscure text leaves in doubt whether Champa had been a possession of Kanishka or just beyond it).[9] Northward, in the second century C.E., the Kushans under Kanishka made various forays into the Tarim Basin, seemingly the original ground of their ancestors the Yuezhi, where they had contacts with the Chinese. Both archaeological findings and literary evidence suggest Kushan rule, in Kashgar, Yarkand and Khotan.[10] As late as the third century C.E., decorated coins of Huvishka had been dedicated at Bodh Gaya together with other gold offerings under the "Enlightenment Throne" of the Buddha, suggesting direct Kushan influence in the area during that period.[11]

Main Kushan rulers

Kujula Kadphises (30–80)

According to the Hou Hanshu (compiled by Fan Ye in the fifth century): "the prince (xihou) of Guishuang (Badakhshan and the adjoining territories north of the Oxus), named Kujula Kadphises (Ch: 丘就却, "Qiujiuque") attacked and exterminated the four other princes (xihou). He set himself up as king of a kingdom called Guishuang."[12]

He invaded Anxi (Parthia) and took the Gaofu (Kabul) region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda, and Jibin (Kapisha-Gandhara). Qiujiuque (Kujula Kadphises) was more than 80 years old when he died. Those conquests probably took place sometime between 45 and 60, and laid the basis for the Kushan Empire which was rapidly expanded by his descendants. Kujula issued an extensive series of coins and fathered at least two sons, Sadaṣkaṇa, known from only two inscriptions, especially the Rabatak inscription, and apparently never have ruled, and apparently Vima Taktu. Kujula Kadphises had been the great grandfather of Kanishka.

Vima Taktu (80–105)

The Rabatak inscription mentions Sadashkana, leaving out mention of Vima Takt[u] (or Tak[to], Ancient Chinese: 阎膏珍 Yangaozhen). He had been the predecessor of Vima Kadphises, and Kanishka I, expanding the Kushan Empire into the northwest of the Indian subcontinent.[13]

Vima Kadphises (105–127)

Vima Kadphises (Kushan language: Οοημο Καδφισης) was a Kushan emperor from around 90–100 C.E., the son of Sadashkana and the grandson of Kujula Kadphises, and the father of Kanishka I, as detailed by the Rabatak inscription.

Vima Kadphises added to the Kushan territory by his conquests in Afghanistan and north-west India. He issued an extensive series of coins and inscriptions. He was the first to introduce gold coinage in India, in addition to the existing copper and silver coinage.

Kanishka I (127–147)

The rule of Kanishka, fifth Kushan king, flourished for at least 28 years from c. 127. Upon his accession, Kanishka ruled a massive territory, covering virtually all of northern India, south to Ujjain and Kundina and east beyond Pataliputra, according to the Rabatak inscription.[14]

He administered the territory from two capitals: Purushapura (now Peshawar in northern Pakistan) and Mathura, in northern India. He, along with Raja Dab, has been identified as the builder of the massive, ancient Fort at Bathinda (Qila Mubarak), in the modern city of Bathinda, Indian Punjab.

The Kushans also had a summer capital in Bagram (then known as Kapisa), where the "Begram Treasure," comprising works of art from Greece to China, has been found. According to the Rabatak inscription, Kanishka had been the son of Vima Kadphises, the grandson of Sadashkana, and the great-grandson of Kujula Kadphises. Kanishka’s era began in 127,[15] used as a calendar reference by the Kushans for about a century, until the decline of the Kushan realm.

Vāsishka

Vāsishka had been a Kushan emperor, who had a short reign following Kanishka. His rule extended as far south as Sanchi (near Vidisa), where several inscriptions in his name have been found, dated to the year 22 (The Sanchi inscription of "Vaksushana" – i. e. Vasishka Kushana) and year 28 (The Sanchi inscription of Vasaska – i. e. Vasishka) of the Kanishka era.

Huvishka (140–183)

Huvishka (Kushan: Οοηϸκι, "Ooishki") had been a Kushan emperor from the death of Kanishka in 140 C.E. until the succession of Vasudeva I, about 40 years later. His rule was a period of retrenchment and consolidation for the Empire. In particular he devoted time and effort early in his reign to the exertion of greater control over the city of Mathura.

Vasudeva I (191–225)

Vasudeva I (Kushan: Βαζοδηο "Bazodeo," Chinese: 波調 "Bodiao") ruled as the last of the "Great Kushans." Named inscriptions dating from year 64 to 98 of Kanishka’s era suggest his reign extended from at least 191 to 225 C.E. The last great Kushan emperor, the end of his rule coincides with the invasion of the Sassanids as far as northwestern India, and the establishment of the Indo-Sassanids or Kushanshahs from around 240 C.E.

Kushan deities

The Kushan religious pantheon varies widely as revealed by their coins and their seals, on which more than 30 different gods appear, belonging to the Hellenistic, the Iranian, and to a lesser extent the Indian world. Greek deities, with Greek names appear on early coins. During Kanishka's reign, the language of the coinage changes to Bactrian though it remained in Greek script for all kings. After Huvishka, only two divinities appear on the coins: Ardoxsho and Oesho.

Representation from Greek mythology and Hellenistic syncretism include:

- Ηλιος (Helios), Ηφαηστος (Hephaistos), Σαληνη (Selene), Ανημος (Anemos). Further, the coins of Huvishka also portray two demi-gods: erakilo Heracles, and sarapo Sarapis.

The Indic entities represented on coinage include:

- Βοδδο (boddo, Buddha)

- Μετραγο Βοδδο (metrago boddo, bodhisattava Maitreya)

- Mαασηνo (maaseno, Mahasena)

- Σκανδo koμαρo (skando komaro, Skanda Kumara)

- Ϸακαμανο Βοδδο (shakamano boddho, Shakyamuni Buddha)

The Iranic entities depicted on coinage include:

- Αρδοχϸο (ardoxsho, Ashi Vanghuhi)

- A?αειχ?o (ashaeixsho, Asha Vahishta)

- Αθϸο (athsho, Atar)

- Φαρρο (pharro, Khwarenah)

- Λροοασπο (lrooaspa, Drvaspa)

- Μαναοβαγο, (manaobago, Vohu Manah)

- Μαο (mao, Mah)

- Μιθρο, Μιιρο, Μιορο, Μιυρο (mithro and variants, Mithra)

- Μοζδοοανο (mozdooano, Mazda *vana "Mazda the victorious?")

- Νανα, Ναναια, Ναναϸαο (variations of pan-Asiatic nana, Sogdian nny, in a Zoroastrian context Aredvi Sura Anahita)

- Οαδο (oado Vata)

- Oαxϸo (oaxsho, "Oxus")

- Ooρoμoζδο (ooromozdo, Ahura Mazda)

- Οραλαγνο (orlagno, Verethragna)

- Τιερο (tiero, Tir)

Additionally,

- Οηϸο (oesho), long considered to represent Indic Shiva,[16] but more recently identified as Avestan Vayu conflated with Shiva.[17]

- Two copper coins of Huvishka bear a 'Ganesa' legend, but instead of depicting the typical theriomorphic figure of Ganesha, have a figure of an archer holding a full-length bow with string inwards and an arrow. Typically a depiction of Rudra, in the case of those two coins Shiva has been represented.

Some deities on Kushan coinage:

Gold coin of Kanishka I, with a depiction of the Buddha, with the legend "Boddo" in Greek script. Ahin Posh.

The Kushans and Buddhism

Cultural exchanges flourished, encouraging the development of Greco-Buddhism, a fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist cultural elements, expanding into central and northern Asia as Mahayana Buddhism. Kanishka has earned renown in Buddhist tradition for having convened a great Buddhist council in Kashmir. Kanishka also had the original Gandhari vernacular, or Prakrit, Buddhist texts translated into the language of Sanskrit. Along with the Indian emperors Ashoka and Harsha Vardhana and the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda), Buddhism considers Kanishka one of its greatest benefactors.

Kushan art

The art and culture of Gandhara, at the crossroads of the Kushan hegemony, constitute the best known expressions of Kushan influences to Westerners. Several direct depictions of Kushans from Gandhara have been discovered, represented with a tunic, belt and trousers and play the role of devotees to the Buddha, as well as the Bodhisattva and future Buddha Maitreya. In the iconography, they have never been associated with the Hellenistic "Standing Buddha" statues (See image) of an earlier historical period. The style of these friezes incorporating Kushan devotees, already strongly Indianized, are quite remote from earlier Hellenistic depictions of the Buddha:

Contacts with Rome

Several Roman sources describe the visit of ambassadors from the Kings of Bactria and India during the second century, probably referring to the Kushans. Historia Augusta, speaking of Emperor Hadrian (117–138) tells:

- "Reges Bactrianorum legatos ad eum, amicitiae petendae causa, supplices miserunt"

- "The kings of the Bactrians sent supplicant ambassadors to him, to seek his friendship."

Also in 138, according to Aurelius Victor (Epitome‚ XV, 4), and Appian (Praef., 7), Antoninus Pius, successor to Hadrian, received some Indian, Bactrian (Kushan) and Hyrcanian ambassadors.

The Chinese Historical Chronicle of the Hou Hanshu also describes the exchange of goods between northwestern India and the Roman Empire at that time: "To the west (Tiazhu, northwestern India) communicates with Da Qin (the Roman Empire). Precious things from Da Qin can be found there, as well as fine cotton cloths, excellent wool carpets, perfumes of all sorts, sugar loaves, pepper, ginger, and black salt." The summer capital of the Kushan in Begram has yielded a considerable amount of goods imported from the Roman Empire, in particular various types of glassware.

Contacts with China

During the first and second century, the Kushan Empire expanded militarily to the north and occupied parts of the Tarim Basin, their original grounds, putting them at the center of the profitable Central Asian commerce with the Roman Empire. They collaborated militarily with the Chinese against nomadic incursion, particularly with the Chinese general Ban Chao against the Sogdians in 84 C.E., who supported a revolt by the king of Kashgar. Around 85 C.E., they also assisted the Chinese general in an attack on Turfan, east of the Tarim Basin.

In recognition for their support to the Chinese, the Kushans requested, but were denied, a Han princess, even after they had sent presents to the Chinese court. In retaliation, they marched on Ban Chao in 86 with a force of 70,000, but, exhausted by the expedition, fell in defeat to smaller Chinese force. The Yuezhi retreated and paid tribute to the Chinese Empire during the reign of the Chinese emperor Han He (89–106).

Around 116, the Kushans under Kanishka established a kingdom centered on Kashgar, also taking control of Khotan and Yarkand, Chinese dependencies in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang. They introduced the Brahmi script, the Indian Prakrit language for administration, and expanded the influence of Greco-Buddhist art which developed into Serindian art. According to records, the Kushans again sent presents to the Chinese court in 158–159 during the reign of the Chinese emperor Han Huan.

Following those interactions, cultural exchanges increased, and Kushan Buddhist missionaries, such as Lokaksema, became active in the Chinese capital cities of Loyang and sometimes Nanjing, where they particularly distinguished themselves by their translation work. They were the first recorded promoters of Hinayana and Mahayana scriptures in China, greatly contributing to the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.

Decline

After the death of Vasudeva I in 225, the Kushan empire split into western and eastern halves. The Persian Sassanid Empire soon subjugated the Western Kushans (in Afghanistan), losing Bactria and other territories. In 248 the Persians defeated them again, deposing the Western dynasty and replacing them with Persian vassals known as the Kushanshas (or Indo-Sassanids).

The Eastern Kushan kingdom based in the Punjab. Around 270, their territories on the Gangetic plain became independent under local dynasties such as the Yaudheyas. Then in the mid fourth century the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta subjugated them. In 360, a Kushan vassal named Kidara overthrew the old Kushan dynasty and established the Kidarite Kingdom. The Kushan style of Kidarite coins indicates they considered themselves Kushans. The Kidarite had been rather prosperous, although on a smaller scale than their Kushan predecessors. The invasions of the White Huns in the fifth century, and later the expansion of Islam, ultimately wiped out those remnants of the Kushan empire.

Main Kushan rulers

History of South Asia (Indian Subcontinent) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone Age | before 3300 B.C.E. | ||||

| Mature Harappan | 2600–1700 B.C.E. | ||||

| Late Harappan | 1700–1300 B.C.E. | ||||

| Iron Age | 1200–300 B.C.E. | ||||

| Maurya Empire | • 321–184 B.C.E. | ||||

| Middle Kingdoms | 230 B.C.E.–1279 C.E. | ||||

| Satavahana | • 230 B.C.E.–220 C.E. | ||||

| Gupta Empire | • 280–550 C.E. | ||||

| Islamic Sultanates | 1206–1596 | ||||

| Mughal Empire | 1526–1707 | ||||

| Sikh Confederacy | 1716-1849 | ||||

| British India | 1858–1947 | ||||

| Modern States | since 1947 | ||||

| Timeline | |||||

- Heraios (c. 1 – 30), first Kushan ruler, generally Kushan ruling period is disputed

- Kujula Kadphises (c. 30 – c. 80)

- Vima Takto, (c. 80 – c. 105) alias Soter Megas or "Great Saviour."

- Vima Kadphises (c. 105 – c. 127) the first great Kushan emperor

- Kanishka I (127 – c. 147)

- Vāsishka (c. 151 – c. 155)

- Huvishka (c. 155 – c. 187)

- Vasudeva I (c. 191 – to at least 230), the last of the great Kushan emperors

- Kanishka II (c. 226 – 240)

- Vashishka (c. 240 – 250)

- Kanishka III (c. 255 – 275)

- Vasudeva II (c. 290 – 310)

- Vasudeva III reported son of Vasudeva III,a King, uncertain.

- Vasudeva IV reported possible child of Vasudeva III,ruling in Kandahar, uncertain

- Vasudeva of Kabul reported Possible child of Vasudeva IV,ruling in Kabul, uncertain.

- Vasudeva IV reported possible child of Vasudeva III,ruling in Kandahar, uncertain

- Vasudeva III reported son of Vasudeva III,a King, uncertain.

- Chhu (c. 310? – 325?)

- Shaka I (c. 325 – 345)

- Kipunada (c. 350 – 375)

| Middle kingdoms of India | ||||||||||||

| Timeline: | Northern Empires | Southern Dynasties | Northwestern Kingdoms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6th century B.C.E. |

|

|

(Persian rule)

(Islamic empires) | |||||||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ Nicholas Sims-Williams and J. Cribb, "A new Bactrian inscription of Kanishka the Great," in Silk Road Art and Archaeology 4 (1995-1996).

- ↑ John Keay. India: A History. (New York: Grove Press, 2000. ISBN 0802137970), 110.

- ↑ Kushan Empire (ca. 2nd century B.C.E.–3rd century C.E.) | Thematic Essay |Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Keay, 110.

- ↑ Iaroslav Lebedynsky. Les Saces: les "Scythes" d'Asie, VIIIe siècle av. J.-C.-IVe siècle apr. J.-C. (Paris: Errance, 2006. ISBN 2877723372), 62.

- ↑ Lebedynsky, 15.

- ↑ John M. Rosenfield. Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. (1967) reprint ed. (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1993. ISBN 8121505798), 41.

- ↑ B.N. Mukherjee, "The Great Kushana Testament," Indian Museum Bulletin Calcutta, 1995. Quoted in: Goyal (2005), 88.

- ↑ Goyal, 93.

- ↑ Rosenfield, 41.

- ↑ British Museum display, Asian Art room.

- ↑ John E. Hill, 2004. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation. [1]. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Hill, John E. 2004. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation.[2]. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Rabatak inscription, Lines 4–6.

- ↑ Harry Falk, 2001. "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuşâņas." Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII 121–136.

- ↑ C. Sivaramamurti. Śatarudrīya: Vibhūti of Śiva's Iconography. (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1976), 56-59.

- ↑ Nicholas Sims-Williams, "Bactrian Language" in Encyclopaedia Iranica. volume 3 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- ↑ Domenico Faccena. Butkara I. Volume III. (Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente), 1980), 77 and following.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Avari, Burjor. India, the Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Sub-Continent from C. 7000 B.C.E. to AD 1200. London: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 9780415356169.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund, Christian Landes, and Christine Sachs. De l'Indus à l'Oxus: archéologie de l'Asie centrale: catalogue de l'exposition. Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes, 2003. ISBN 2951667922. (in French)

- Faccenna, Domenico. Butkara I. Volume I (Reports on the Campaigns, 1956-1958, in Swat (Pakistan). Volumes II & III (Sculptures from the Sacred Areas of Buktara I & II) Swāt, Pakistan: 1956-1962, Volume III. Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente), 1980. (in English)

- Falk, Harry. Silk Road Art and Archaeology IV (1995-1996).

- Falk, Harry. "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣāṇas." Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII. (2001):121-136.

- Falk, Harry. "The Kaniṣka era in Gupta records." Harry Falk. Silk Road Art and Archaeology X (2004):167–176.

- Goyal, Śrīrāma. Ancient Indian Inscriptions: Recent Finds and New Interpretations. Jodhpur: Kusumanjali Book World, 2005. OCLC 65341609

- Hill, John E. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation. [3], 2004.

- Hill, John E. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 C.E. Draft annotated English translation. [4], 2004.

- Institute of Silk Road Studies. 1990. Silk Road art and archaeology. Kamakura-shi, Japan: Institute of Silk Road Studies. OCLC 187452343.

- Keay, John. India: A History. New York: Grove Press, 2000. ISBN 0802137970.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. Les Saces: les "Scythes" d'Asie, VIIIe siècle av. J.-C.-IVe siècle apr. J.-C. Paris: Errance, 2006. ISBN 2877723372.

- Mukherjee, B.N. "The Great Kushana Testament," Indian Museum Bulletin Calcutta: 1995. Quoted in: Śrīrāma Goyal. Ancient Indian Inscriptions: Recent Finds and New Interpretations. 2005.

- Rosenfield, John M. Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. (1967) reprint ed. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1993. ISBN 8121505798.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas, and J. Cribb, "A new Bactrian inscription of Kanishka the Great," in Silk Road Art and Archaeology 4 (1995-1996).

- Sivaramamurti, C. Śatarudrīya: Vibhūti of Śiva's Iconography. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1976. OCLC 9323693

External links

All links retrieved March 7, 2025.

| ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.