Mannerism

Mannerism marks a period and a style of European painting, sculpture, architecture and decorative arts lasting from the later years of the Italian High Renaissance, around 1520, until the arrival of the Baroque around 1600. Stylistically, it identifies a variety of individual approaches influenced by, and reacting to, the harmonious ideals associated with Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and early Michelangelo. Mannerism is notable for its artificial, as opposed to naturalistic, and its intellectual, qualities.

The term is also applied to some Late Gothic painters working in northern Europe from about 1500 to 1530, especially the Antwerp Mannerists and some currents of seventeenth-century literature, such as poetry. Subsequent mannerists stressed intellectual conceits and artistic ability, features that led early critics to accuse them of working in an unnatural and affected "manner" (maniera).

Historically, Mannerism is a useful designation for sixteenth-century art that emphasizes artificiality over naturalism, and reflects a growing self-consciousness of the artist.

Nomenclature

The word derives from the Italian term maniera, or "style," which corresponds to an artist's characteristic "touch" or recognizable "manner." Artificiality, as opposed to Renaissance and Baroque naturalism, is one of the common features of mannerist art. Its lasting influence during the Italian Renaissance has been transformed by succeeding generations of artists.

As a stylistic label, "Mannerism" is not easily defined. It was first popularized by German art historians in the early twentieth-century, to categorize the types of art that did not fit a particular label belonging to the Italian sixteenth century.

The term is applied differently to a variety of different artists and styles.

Anti-Classical

The early Mannerists—especially Jacopo da Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino in Florence, Raphael's student in Rome Giulio Romano and Parmigianino in Parma—are notable for elongated forms, exaggerated, out-of-balance poses, manipulated irrational space, and unnatural lighting. These artists matured under the influence of the High Renaissance, and their style has been characterized as a reaction to it, or exaggerated extension of it. Therefore, this style is often identified as "anti-classical" mannerism.[1]

Maniera

Subsequent mannerists stressed intellectual conceits and artistic ability, features that led early critics to accuse them of working in an unnatural and affected "manner" (maniera). These artists held their elder contemporary, Michelangelo, as their prime example. Giorgio Vasari, as artist and architect, exemplified this strain of Mannerism lasting from about 1530 to 1580. Based largely at courts and in intellectual circles around Europe, it was often called the "stylish" style or the Maniera.[2]

Mannerisms

After 1580 in Italy, a new generation of artists including the Carracci, Caravaggio and Cigoli, re-emphasized naturalism. Walter Friedlaender identified this period as "anti-mannerism," just as the early mannerists were "anti-classical" in their reaction to the High Renaissance.[3] Outside of Italy, however, mannerism continued into the seventeenth century. Important centers include the court of Rudolf II in Prague, as well as Haarlem and Antwerp.

Mannerism as a stylistic category is less frequently applied to English visual and decorative arts, where local categories such as "Elizabethan" and "Jacobean" are more common. Eighteenth-century Artisan Mannerism is one exception.[4]

Historically, Mannerism is a useful designation for sixteenth-century art that emphasizes artificiality over naturalism, and reflects a growing self-consciousness of the artist.

History

The early Mannerists are usually set in stark contrast to High Renaissance conventions; the immediacy and balance achieved by Raphael's School of Athens, no longer seemed relevant or appropriate. Mannerism developed among the pupils of two masters of the classical approach, with Raphael's assistant Giulio Romano and among the students of Andrea del Sarto, whose studio produced the quintessentially Mannerist painters Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Michelangelo displayed tendencies towards Mannerism, notably in his vestibule to the Laurentian Library and the figures on his Medici tombs.

Mannerist centers in Italy were Rome, Florence and Mantua. Venetian painting, in its separate "school," pursued a separate course, represented in the long career of Titian.

In the mid to late 1500s Mannerism flourished at European courts, where it appealed to knowledgeable audiences with its arcane iconographic programs and sense of an artistic "personality." It reflected a growing trend in which a noticeable purpose of art was to inspire awe and devotion, and to entertain and educate.

Giorgio Vasari

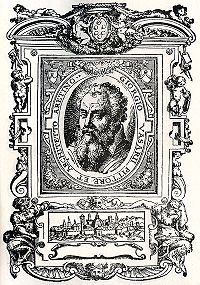

Giorgio Vasari's opinions about the "art" of creating art are evident in his praise of fellow artists in the great book that lay behind this frontispiece: he believed that excellence in painting demanded refinement, richness of invention (invenzione), expressed through virtuoso technique (maniera), and wit and study that appeared in the finished work—all criteria that emphasized the artist's intellect and the patron's sensibility. The artist was now no longer just a craftsman member of a local Guild of St Luke. Now he took his place at court with scholars, poets, and humanists, in a climate that fostered an appreciation for elegance and complexity. The coat-of-arms of Vasari's Medici patrons appear at the top of his portrait, quite as if they were the artist's own.

The framing of the engraved frontispiece to Mannerist artist Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (illustration, left) would be called "Jacobean" in an English-speaking context. In it, Michelangelo's Medici tombs inspire the anti-architectural "architectural" features at the top, the papery pierced frame, the satyr nudes at the base. In the vignette of Florence at the base, papery or vellum-like material is cut and stretched and scrolled into a cartouche (cartoccia). The design is self-conscious, overcharged with rich, artificially "natural" detail in physically improbable juxtapositions of jarring scale changes, overwhelming as a mere frame—Mannerist.

Gian Paolo Lomazzo

Another literary source from the period is Gian Paolo Lomazzo, who produced two works—one practical and one metaphysical—that helped define the Mannerist artist's self-conscious relation to his art. His Trattato dell'arte della pittura, scoltura et architettura (Milan, 1584) was in part a guide to contemporary concepts of decorum, which the Renaissance inherited in part from Antiquity, but Mannerism elaborated upon. Lomazzo's systematic codification of aesthetics, which typifies the more formalized and academic approaches of the later sixteenth century, included a consonance between the functions of interiors and the kinds of painted and sculpted decors that would be suitable. Iconography, often convoluted and abstruse, was a more prominent element in the Mannerist styles. His less practical and more metaphysical Idea del tempio della pittura ("The ideal temple of painting," Milan, 1590) offered a description employing the "four temperaments" theory of human nature and personality, and contained explanations of the role of individuality in judgment and artistic invention.

Some Mannerist Examples

Jacopo da Pontormo

Jacopo da Pontormo's Joseph in Egypt stood in what would have been considered contradicting colors and disunified time and space in the Renaissance. Neither the clothing, nor the buildings—not even the colors—accurately represented the Bible story of Joseph. It was wrong, but it stood out as an accurate representation of society's feelings.

Rosso Fiorentino

Rosso Fiorentino, who had been a fellow-pupil of Pontormo in the studio of Andrea del Sarto, brought Florentine mannerism to Fontainebleau in 1530, where he became one of the founders of the French sixteenth-century Mannerism called the "School of Fontainebleau."

School of Fontainebleau

The examples of a rich and hectic decorative style at Fontainebleau transferred the Italian style, through the medium of engravings, to Antwerp and thence throughout Northern Europe, from London to Poland, and brought Mannerist design into luxury goods like silver and carved furniture. A sense of tense controlled emotion expressed in elaborate symbolism and allegory, and elongated proportions of female beauty are characteristics of his style.

Angelo Bronzino

Agnolo Bronzino's somewhat icy portraits (illustrated, to the left) put an uncommunicative abyss between sitter and viewer, concentrating on rendering of the precise pattern and sheen of rich textiles.

Alessandro Allori

Alessandro Allori's (1535 - 1607) Susanna and the Elders (illustrated, right) uses artificial, waxy eroticism and consciously brilliant still life detail, in a crowded contorted composition.

Jacopo Tintoretto

Jacopo Tintoretto's Last Supper (left) epitomizes Mannerism by taking Jesus and the table out of the middle of the room.

He showed all that was happening. In sickly, disorienting colors he painted a scene of confusion that somehow separated the angels from the real world. He had removed the world from God's reach.

El Greco

El Greco attempted to express the religious tension with exaggerated Mannerism. This exaggeration would serve to cross over the Mannerist line and be applied to Classicism. After the realistic depiction of the human form and the mastery of perspective achieved in high Renaissance Classicism, some artists started to deliberately distort proportions in disjointed, irrational space for emotional and artistic effect. There are aspects of Mannerism in El Greco (illustration, right), such as the jarring "acid" color sense, elongated and tortured anatomy, irrational perspective and light of his crowded composition, and obscure and troubling iconography.

Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini created a salt cellar of gold and ebony in 1540 featuring Neptune and Amphitrite (earth and water) in elongated form and uncomfortable positions. It is considered a masterpiece of Mannerist sculpture.

Mannerist architecture

An example of mannerist architecture is the Villa Farnese at Caprarola in the rugged country side outside of Rome. The proliferation of engravers during the sixteenth century spread Mannerist styles more quickly than any previous styles. A center of Mannerist design was Antwerp during its sixteenth-century boom. Through Antwerp, Renaissance and Mannerist styles were widely introduced in England, Germany, and northern and eastern Europe in general. Dense with ornament of "Roman" detailing, the display doorway at Colditz Castle (illustration, left) exemplifies this northern style, characteristically applied as an isolated "set piece" against unpretentious vernacular walling.

Mannerist literature

In English literature, Mannerism is commonly identified with the qualities of the "Metaphysical" poets of whom the most famous is John Donne. The witty sally of a Baroque writer, John Dryden, against the verse of Donne in the previous generation, affords a concise contrast between Baroque and Mannerist aims in the arts:

- "He affects the metaphysics, not only in his satires, but in his amorous verses, where nature only should reign; and perplexes the minds of the fair sex with nice[5] speculations of philosophy when he should engage their hearts and entertain them with the softnesses of love" (italics added).

Notes

- ↑ W. Friedlaender, Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting (New York, 1957).

- ↑ John Shearman, Mannerism (Harmondsworth, 1967).

- ↑ W. Friedlaender, Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting (New York, 1957).

- ↑ John Summerson, Architecture in Britain (New York, 1983), 157-72.

- ↑ 'Nice' in the sense of 'finely reasoned.'

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gardner, Helen. Metaphysical Poets, Selected and Edited. Introduction.

- Giuliano Briganti, 1962. Italian Mannerism (Originally published in Italian, 1961).

- Shearman, John. 1967. Mannerism. A classic summation.

- Sypher, Wylie. Four Stages of Renaissance Style: Transformations in Art and Literature, 1400-1700, 1955. A classic analysis of Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, and Late Baroque.

- W. Friedlaender. Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting. New York, 1957.

- Würtenberger, Franzsepp. 1963. Mannerism: The European Style of the Sixteenth Century. (Originally published in German, 1962).

| El Greco |

|---|

| General: The Artist | Chronology | Technique and style | Posthumous fame | Cretan School | Spanish Renaissance | Mannerism Paintings: List of notable works | The Dormition of the Virgin | The Disrobing of Christ (El Espolio) | The Burial of the Count of Orgaz | View of Toledo | Opening of the Fifth Seal | The Adoration of the Shepherds |

| Western art movements |

| Renaissance · Mannerism · Baroque · Rococo · Neoclassicism · Romanticism · Realism · Pre-Raphaelite · Academic · Impressionism · Post-Impressionism |

| 20th century |

| Modernism · Cubism · Expressionism · Abstract expressionism · Abstract · Neue Künstlervereinigung München · Der Blaue Reiter · Die Brücke · Dada · Fauvism · Art Nouveau · Bauhaus · De Stijl · Art Deco · Pop art · Futurism · Suprematism · Surrealism · Minimalism · Post-Modernism · Conceptual art |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.