Peace of Westphalia

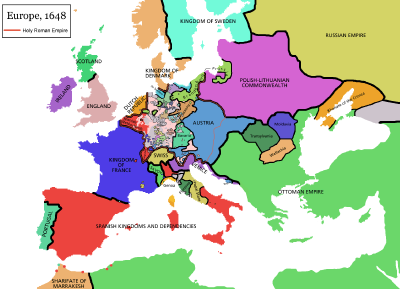

The Peace of Westphalia refers to the pair of treaties (the Treaty of Münster and the Treaty of Osnabrück) signed in October and May 1648 which ended both the Thirty Years' War and the Eighty Years' War. The treaties were signed on October 24 and May 15, 1648 and involved the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, the other German princes, Spain, France, Sweden, and representatives from the Dutch republic. The Treaty of the Pyrenees, signed in 1659, ending the war between France and Spain, is also often considered part of the treaty.

The peace as a whole is often used by historians to mark the beginning of the modern era. Each ruler would have the right to determine their state's religion—thus, in law, Protestantism and Catholicism were equal. The texts of the two treaties are largely identical and deal with the internal affairs of the Holy Roman Empire.[1]

The Peace of Westphalia continues to be of importance today, with many academics asserting that the international system that exists today began at Westphalia. Both the basis and the result of this view have been attacked by revisionist academics and politicians alike, with revisionists questioning the significance of the Peace, and commentators and politicians attacking the "Westphalian System" of sovereign nation-states. The concept of each nation-state, regardless of size, as of equal legal value informed the founding of the United Nations, where all member states have one vote in the General Assembly. In the second half of the twentieth century, the democratic nation state as the pinnacle of political evolution saw membership of the UN rise from 50 when it was founded to 192 at the start of the twenty-first century. However, many new nations were artificial creations from the colonial division of the world, reflecting the economic interests of the colonizers rather than local cultural, ethnic, religious or other significant boundaries which serve as the foundation of cohesive societies.

The aspiration to become a sovereign nation-state so dominated the decolonization process that alternative possibilities, such as confederacy, were ignored. Westphalia, however, saw an end to countries as the personal possession of their monarchs and the beginning of respect for the territorial integrity of other nations. It did not, however, see the end of imperial expansion, since the European nations applied one rule to themselves and another to the peoples whom they encountered beyond Europe, whose territory could simply be appropriated, partitioned and exploited. Those who champion a more just sharing of the earth's resources and some form of global governance see the Westphalian nation-state as an obstacle; nations are reluctant to act except from self-interest and are disinclined to relinquish power to any external body, which is understood as undermining their sovereignty. In Europe, as the European Union evolves towards becoming a European government, member states resist this on the grounds that their sovereignty is threatened.

Locations

The peace negotiations were held in the cities of Münster and Osnabrück, which lie about 50 kilometers apart in the present-day German states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony. Sweden had favored Münster and Osnabrück while the French had proposed Hamburg and Cologne. In any case two locations were required because Protestant and Catholic leaders refused to meet each other. The Catholics used Münster, while the Protestants used Osnabrück.

Results

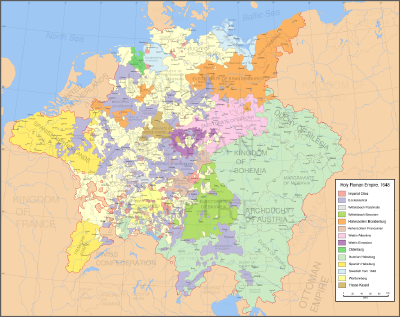

Internal political boundaries

The power which Ferdinand III had taken for himself in contravention of the Holy Roman Empire's constitution was stripped, meaning that the rulers of the German states were again able to determine the religion of their lands. Protestants and Catholics were redefined as equal before the law, and Calvinism was given legal recognition.[2]

Tenets

The main tenets of the Peace of Westphalia were:

- All parties would now recognize the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, by which each prince would have the right to determine the religion of his own state, the options being Catholicism, Lutheranism, and now Calvinism (the principle of cuius regio, eius religio).[2]

- Christians living in principalities where their denomination was not the established church were guaranteed the right to practice their faith in public during allotted hours and in private at their will.[3]

There were also territorial adjustments:

- The majority of the Peace's terms can be attributed to the work of Cardinal Mazarin, the de facto leader of France at the time (the king, Louis XIV, was still a child). Not surprisingly, France came out of the war in a far better position than any of the other participants. France won control of the bishoprics of Metz, Toul, Verdun in Lorraine, the Habsburg lands in Alsace (the Sundgau), and the cities of the Décapole in Alsace (but not Strasbourg, the Bishopric of Strasbourg, or Mulhouse).

- Sweden received an indemnity, as well as control of Western Pomerania and the Prince-Bishoprics of Bremen and Verden. It thus won control of the mouth of the Oder, Elbe, and Weser Rivers, and acquired three voices in the Council of Princes of the German Reichstag.

- Bavaria retained the Palatinate's vote in the Imperial Council of Electors (which elected the Holy Roman emperor), which it had been granted by the ban on the Elector Palatine Frederick V in 1623. The Prince Palatine, Frederick's son, was given a new, eighth electoral vote.

- Brandenburg (later Prussia) received Farther Pomerania, and the bishoprics of Magdeburg, Halberstadt, Kammin, and Minden.

- The succession to the dukes of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, who had died out in 1609, was clarified. Jülich, Berg, and Ravenstein were given to the Count Palatine of Neuburg, while Cleves, Mark, and Ravensberg went to Brandenburg.

- It was agreed that the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück would alternate between Protestant and Catholic holders, with the Protestant bishops chosen from cadets of the House of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

- The independence of the city of Bremen was clarified.

- The hundreds of German principalities were given the right to ratify treaties with foreign states independently, with the exception of any treaty which would negatively affect the Holy Roman Empire.

- The Palatinate was divided between the re-established Elector Palatine Charles Louis (son and heir of Frederick V) and Elector-Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, and thus between the Protestants and Catholics. Charles Louis obtained the Lower Palatinate along the Rhine, while Maximilian kept the Upper Palatinate, to the north of Bavaria.

- Barriers to trade and commerce erected during the war were abolished, and 'a degree' of free navigation was guaranteed on the Rhine.[4]

Significance in international relations theory

Traditional realist view

The Peace of Westphalia is crucially important to modern international relations theory, with the Peace often being defined as the beginning of the international system with which the discipline deals.[1][4]

International relations theorists have identified the Peace of Westphalia as having several key principles, which explain the Peace's significance and its impact on the world today:

- The principle of the sovereignty of states and the fundamental right of political self determination

- The principle of (legal) equality between states

- The principle of non-intervention of one state in the internal affairs of another state

These principles are common to the way the dominant international relations paradigm views the international system today, which explains why the system of states is referred to as “The Westphalian System.”

Revisionist view

The above interpretation of the Peace of Westphalia is not without its critics. Revisionist historians and international relations theorists argue against all of these points.

- Neither of the treaties mention sovereignty. Since the three chief participants (France, Sweden, and Holy Roman Empire) were all already sovereign, there was no need to clarify this situation.[1] In any case, the princes of Germany remained subordinate to the Holy Roman emperor as per the constitution.

- While each German principality had its own legal system, the final Courts of Appeal applied to the whole of the Holy Roman Empire—the final appellate was the emperor himself, and his decisions in cases brought to him were final and binding on all subordinates.[1] The emperor could, and did, depose princes when they were found by the courts to be at fault.[5]

- Both treaties specifically state that should the treaty be broken, France and Sweden held the right to intervene in the internal affairs of the Empire.[1]

Rather than cementing sovereignty, revisionists hold that the treaty served to maintain the status quo ante. Instead, the treaty cemented the theory of Landeshoheit, in which state-like actors have a certain (usually high) degree of autonomy, but are not sovereign since they are subject to the laws, judiciary and constitution of a higher body.[1]</ref>

Modern views on the Westphalian System

The Westphalian System is used as a shorthand by academics to describe the system of states which the world is made up of today.[1]

In 1998 a symposium on the continuing political relevance of the Peace of Westphalia, then–NATO Secretary General Javier Solana said that "humanity and democracy [were] two principles essentially irrelevant to the original Westphalian order" and levied a criticism that "the Westphalian system had its limits. For one, the principle of sovereignty it relied on also produced the basis for rivalry, not community of states; exclusion, not integration."[6]

In 2000, then–German foreign minister Joschka Fischer referred to the Peace of Westphalia in his Humboldt Speech, which argued that the system of European politics set up by Westphalia was obsolete:

The core of the concept of Europe after 1945 was and still is a rejection of the European balance-of-power principle and the hegemonic ambitions of individual states that had emerged following the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, a rejection which took the form of closer meshing of vital interests and the transfer of nation-state sovereign rights to supranational European institutions.[7]

It has also been claimed that globalization is bringing an evolution of the international system past the sovereign Westphalian state.[8]

However, European nationalists and some American paleoconservatives such as Pat Buchanan hold a favorable view of the Westphalian state.[9] Supporters of the Westphalian state oppose socialism and some forms of capitalism for undermining the nation-state. A major theme of Buchanan's political career, for example, has been attacking globalization, critical theory, neoconservatism, and other philosophies he considers detrimental to today's Western nations.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Andreas Osiander, “Sovereignty, International Relations, and the Westphalian Myth,” International Organization 55(2) (Spring 2001): 251-287.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 R.J. Barro and R.M. McCleary. Which Countries have State Religions? Harvard University (February 2005). Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ↑ The Peace of Westphalia (excerpts) Münster, October 24, 1648. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Leo Gross, The Peace of Westphalia, The American Journal of International Law 42 (1) (January 1948): 20-41.

- ↑ Werner Trossbach, “Furstenabsetzungen im 18. Jahrhundert,” Zeitschrift fur historische Forschung 13 (1986): 425-454.

- ↑ Javier Solana, Securing Peace in Europe NATO (Nov. 12, 1998). Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ↑ Joschka Fischer, From Confederacy to Federation - Thoughts on the Finality of European Integration Humboldt University in Berlin (May 12, 2000). Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ↑ A. Claire Cutler, Critical Reflections on the Westphalian Assumptions of International Law and Organization: A Crisis of Legitimacy Review of International Studies 27 (2001): 133-150.

- ↑ Patrick J. Buchanan, Say Goodbye to the Mother Continent Patrick J. Buchanan Official Website (January 1, 2002). Retrieved August 15, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Croxton, Derek, and Anuschka Tischer. The Peace of Westphalia: A Historical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0313310041

- Guthrie, William P. The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0313324086

- Walker, Thomas Alfred. A History of the Law of Nations: From the Earliest Times to the Peace of Westphalia, 1648. Buffalo, NY: Willam S. Hein & Co., 2004. ISBN 978-1575888316

External links

All links retrieved August 15, 2023.

- Treaty of Westphalia Text – The Avalon Project at Yale Law School

- The Peace of Westphalia - 1648 Holy Roman Empire Association

- Kelly, Michael J. Pulling at the Threads of Westphalia: Involuntary Sovereignty Waiver - Revolutionary International Legal Theory or Return to Rule by the Great Powers? UCLA Journal of International Law & Foreign Affairs 10:2 (2005).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.