Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (sometimes also known as the Lagids, from the name of Ptolemy I's father, Lagus) was a Hellenistic Macedonian royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt for nearly 300 years, from 305 B.C.E. to 30 B.C.E. Ptolemy, a somatophylax, one of the seven bodyguards who served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap (Governor) of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 B.C.E. In 305 B.C.E., he declared himself King Ptolemy I, later known as "Soter" (savior). The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 B.C.E. All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy. Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called Cleopatra, Arsinoe, or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt. Chauveau says that the "ever increasing importance assumed by its women" was a distinctive feature of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[1]

A flourishing center of learning and scholarship, Ptolemaic Egypt gave the world the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, important developments in mathematics and medicine and its greatest library, sadly destroyed. The Ptolemies continued Alexander the Great's practice of cultural fusion, blending Greek and Egyptian customs and beliefs and practices together, creating a synthesis that remains a subject for study and research. This society did not implode or collapse due to any type of internal weakness but fell to a superior military power. This cultural synthesis inspired the work of the Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria as it did the cultural context in which gnosticism later flourished.[2] Against the view of some that multiculturalism is a chimera, the Ptolemaic period of Egypt's history can be examined as an example of a flourishing, vibrant polity.[3]

Ptolemaic rulers and consorts

The dates in brackets are regal dates for the kings. They frequently ruled jointly with their wives, who were often also their sisters. Several queens exercised regal authority, but the most famous and successful was Cleopatra VII (51 B.C.E.-30 B.C.E.), with her two brothers and her son as successive nominal co-rulers. Several systems exist for numbering the later rulers; the one used here is the one most widely used by modern scholars. Dates are years of reign.

- Ptolemy I Soter (305 B.C.E.-282 B.C.E.) married first (probably) Thais, secondly Artakama, thirdly Eurydice]] and finally Berenice I

- Ptolemy II Philadelphus (284 B.C.E.-246 B.C.E.) married Arsinoe I, then Arsinoe II Philadelphus; ruled jointly with Ptolemy the Son (267 B.C.E.-259 B.C.E.)

- Ptolemy III Euergetes (246 B.C.E.-222 B.C.E.) married Berenice II

- Ptolemy IV Philopator (222 B.C.E.-204 B.C.E.) married Arsinoe III

- Ptolemy V Epiphanes (204 B.C.E.-180 B.C.E.) married Cleopatra I

- Ptolemy VI Philometor (180 B.C.E.-164 B.C.E., 163 B.C.E.-145 B.C.E.) married Cleopatra II, briefly ruled jointly with Ptolemy Eupator in 152 B.C.E.

- Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator (never reigned)

- Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II (Physcon) (170 B.C.E.-163 B.C.E., 145 B.C.E.-116 B.C.E.) married Cleopatra II then Cleopatra III; temporarily expelled from Alexandria by Cleopatra II between 131 B.C.E. and 127 B.C.E., reconciled with her in 124 B.C.E.

- Cleopatra II Philometora Soteira (131 B.C.E.-127 B.C.E.), in opposition to Ptolemy VIII

- Cleopatra III Philometor Soteira Dikaiosyne Nikephoros (Kokke) (116 B.C.E.-101 B.C.E.) ruled jointly with Ptolemy IX (116 B.C.E.-107 B.C.E.) and Ptolemy X (107 B.C.E.-101 B.C.E.)

- Ptolemy IX Soter II (Lathyros) (116 B.C.E.-107 B.C.E., 88 B.C.E.-81 B.C.E. as Soter II) married Cleopatra IV then Cleopatra Selene; ruled jointly with Cleopatra III in his first reign

- Ptolemy X Alexander I (107 B.C.E.-88 B.C.E.) married Cleopatra Selene then Berenice III; ruled jointly with Cleopatra III till 101 B.C.E.

- Berenice III Philopator (81 B.C.E.-80 B.C.E.)

- Ptolemy XI Alexander II (80 B.C.E.) married and ruled jointly with Berenice III before murdering her; ruled alone for 19 days after that.

- Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos (Auletes) (80 B.C.E.-58 B.C.E., 55 B.C.E.-51 B.C.E.) married Cleopatra V Tryphaena

- Cleopatra V Tryphaena (58 B.C.E.-57 B.C.E.) ruled jointly with Berenice IV Epiphaneia (58 B.C.E.-55 B.C.E.)

- Cleopatra VII Philopator (51 B.C.E.-30 B.C.E.) ruled jointly with Ptolemy XIII (51 B.C.E.-47 B.C.E.), Ptolemy XIV (47 B.C.E.-44 B.C.E.) and Ptolemy XV Caesarion (44 B.C.E.-30 B.C.E.)

- Arsinoe IV (48 B.C.E.-47 B.C.E.) in opposition to Cleopatra VII

Simplified Ptolemaic family tree

Many of the relationships shown in this tree are controversial.

Other members of the Ptolemaic dynasty

- Ptolemy Keraunos (died 279 B.C.E.)—eldest son of Ptolemy I Soter. Eventually became king of Macedon.

- Ptolemy Apion (died 96 B.C.E.)—son of Ptolemy VIII Physcon. Made king of Cyrenaica. Bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome.

- Ptolemy Philadelphus (born 36 B.C.E.)—son of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII.

- Ptolemy of Mauretania (died 40 C.E.)—son of Juba II of Mauretania and Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony. King of Mauretania.

Achievements

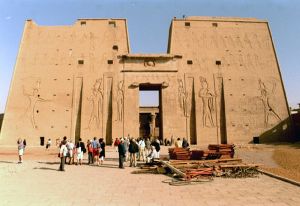

Alexander the Great built the city of Alexandria and began to collect books to establish a library. This project was continued by the Ptolemies, who transformed Alexandria into a leading cultural center. The Alexandria Library became the most famous and important in the ancient Meditaerranean world. The Ptolemies adapted many aspects of Egyptian life and customs, claiming the title of Pharaoh and being recognized by the population as the their legitimate successors and the 31st Dynasty. They took part in Egyptian religious practices and were depicted on monuments in Egyptian dress. They constructed Temples, which were often consecrated during their state visits to the provinces.[4] These Temples include those at Edfu, Deir el-Medina and one in Luxor. Learning flourished and a synthesis between Greek and Egyptian culture developed. In this, the Ptolemies continued Alexander's project of cultural fusion. Like the Pharaohs, they claimed to be sons and daughters of the Sun God, Ra. They not only called themselves Pharaoh but used all the titles of the earlier Egyptian rulers. Alexandria was also an economic center of significance. It was from Egypt of the Ptolemaic dynasty that the cult of Isis spread throughout the Roman Empire.[5]

During the Ptolemaic period, the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew bible, was produced in Alexandria, which was also an important center for Jewish life. This translation was undergone at the request of the Ptolemaic Pharaoh. In its turn, it stimulated "and nourished the discipline of exegesis, which would so profoundly mark the development of both Judaism and Christianity."[6] Towards the very end of the Ptolemaic period, the Jewish philosopher Philo (20 B.C.E.-50 C.E.) set out to fuse Jewish and Greek thought. Euclid of Alexandria (325-265 B.C.E.) and Archimedes of Syracuse (287-212 B.C.E.) were among Alexandria's most distinguished scholars. Philometer VI had a Jewish tutor, the famous Aristobulus. During the reign of Ptolemy V, new critical editions of Homer, Hesiod and Pindar were produced at the great library.[7] It was also in Alexandria that the writings on medicine that "form our Hippocratic Corpus were first brought together."[8]

Decline

There were revolts due to a succession of incompetent rulers. However, it was Rome's strength rather than Egypt's weakness that brought about the end of the Ptolemaic period. After defeating Carthage in the Punic Wars, Roman power was on the ascendancy. When Cleopatra became Queen, Roman expansion was unstoppable.

Legacy

Hoelbl writes that "The Ptolemaic period has provided us with a great cultural legacy in the form of the impressive temples and Alexandrian scholarship which we still enjoy."[9] The main value of the Ptolemaic legacy lies in its fusion of Greek and Egyptian culture, producing what was effectively a bi-cultural civilization. This civilization did not collapse or implode but eventually fell to the Romans due to their superior military strength. For nearly three centuries, Ptolemaic Egypt was a vibrant, productive, creative and in the main peaceful center of learning, commerce and trade in the Ancient world. In contrast, Samuel P. Huntington's Clash of the Civilizations thesis argues that no society that straddles across cultures, which does not identify with a single culture, can thrive. History, he says "shows that no country so constituted can … endure."[10]

Notes

- ↑ Chauveau (2000), 30.

- ↑ Douglas M. Parrott, Gnosticism and Egyptian Religion, Novum Testamentum 29 (1): 79-93.

- ↑ Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996, ISBN 9780684811642).

- ↑ Chauveau (2000), 43.

- ↑ Oswald, Peter, and Apuleius, The Golden Ass, or The Curious Man (London: Oberon, 2002, ISBN 9781840022858).

- ↑ Chauveau (2000), 173.

- ↑ Hoelbl (2000), 191.

- ↑ Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 9780415086110), 130.

- ↑ Hoelbl (2000), 8.

- ↑ Huntington (1996), 306.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chauveau, Michel. 2000. Egypt in the age of Cleopatra: History and Society Under the Ptolemies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801435973.

- Fazzini, Richard A., and Robert Steven Bianchi. 1988. Cleopatra's Egypt: Age of the Ptolemies. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum. ISBN 9780872731134.

- Hoelbl, Gunther. 2000. A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415201452.

- Lampela, Anssi. 1998. Rome and the Ptolemies of Egypt: The Development of Their Political Relations, 273-80 B.C.E. Helsinki, FI: Societas Scientiarum Fennica. ISBN 9789516532953.

- Sprott, Duncan. 2004. The Ptolemies. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9781400041541.

- Stanwick, Paul Edmund. 2002. Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292777729.

External links

All links retrieved December 2, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.