Sociology of religion

| Sociology |

| Subfields |

|---|

|

Comparative sociology ·

Cultural sociology |

| Perspectives |

|

Conflict theory · Critical theory |

| Related Areas |

|

Criminology |

The sociology of religion is primarily the study of the practices, social structures, historical backgrounds, development, universal themes, and roles of religion in society. There is particular emphasis on the recurring role of religion in nearly all societies on Earth today and throughout recorded history. Sociologists of religion attempt to explain the effects of society on religion and the effects of religion on society; in other words, their dialectical relationship.

Historically, sociology of religion was of central importance to sociology, with early seminal figures such as Émile Durkheim, and Max Weber writing extensively on the role of religion in society. Today, sociologists have broadened their areas of interest, and for many religion is no longer considered key to the understanding of society. However, many others continue to study the role of religion, particularly New Religious Movements, both for the individual and as it affects our increasingly multi-cultural society. In order to establish a world of peace, harmony among religions is essential. Sociology of religion is a field that should have much to contribute to the understanding necessary to advance such a world.

History and relevance today

The classical, seminal sociological theorists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were greatly interested in religion and its effects on society. These theorists include Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Karl Marx. Like Plato and Aristotle from Ancient Greece, and Enlightenment philosophers from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, the ideas posited by these sociologists continue to be addressed today. More recent prominent sociologists of religion include Peter Berger, Michael Plekon, Rodney Stark, Robert Wuthnow, James Davison Hunter, Andrew Greeley, and Christian Smith.

Despite the claims of many classical theorists and sociologists immediately after World War II, religion has continued to play a vital role in the lives of individuals worldwide. In America, for example, church attendance has remained relatively stable in the past 40 years. In Africa and South America, the emergence of Christianity has occurred at a startling rate. While Africa could claim roughly 10 million Christians in 1900, by the beginning of the twenty-first century estimates put that number closer to 200 million. The rise of Islam as a major world religion, especially its new-found influence in the West, is another significant development. In short, presupposed secularization (the decline of religiosity) might seem to be a myth, depending on its definition and the definition of its scope. For instance, some sociologists have argued that steady church attendance and personal religious belief may coexist with a decline in the influence of religious authorities on social or political issues.

The view of religion in classical sociology

Comte had a novel perspective on religion and sociology. Durkheim, Marx, and Weber had very complex and developed theories about the nature and effects of religion. Durkheim and Weber, specifically, are often difficult to understand, especially in light of the lack of context and examples in their primary texts. Religion was considered to be an extremely important social variable in the work of all three.

Auguste Comte

Initially, Auguste Comte argued that religion was a social glue keeping the disparate sects of society intact. This idea was in line with his belief that society operated as a single organism. Language and the division of labor also performed a similar social bonding role. Comte later came to elevate sociology itself to a religion. He saw his positivist system as the source of love, which alienated his intellectual followers who were dedicated to ideas of rationalism.

Comte's aim was to discover the sequence through which humankind transformed itself from that of barely different from apes to that of the civilized Europe of his day. Applying his scientific method, Comte produced his "Law of Human Progress" or the "Law of Three Stages," based on his realization that

Phylogeny, the development of human groups or the entire human race, is retraced in ontogeny, the development of the individual human organism. Just as each one of us tends to be a devout believer in childhood, a critical metaphysician in adolescence, and a natural philosopher in manhood, so mankind in its growth has traversed these three major stages.[1]

Thus, Comte stated each department of knowledge passes through three stages: The theological, the metaphysical, and the positive, or scientific.

The "Theological" phase was seen from the perspective of nineteenth century France as preceding the Enlightenment, in which humanity's place in society and society's restrictions upon humans were referenced to God. Comte believed all primitive societies went through some period in which life is completely theocentric. In such societies, the family is the prototypical social unit, and priests and military leaders hold sway. From there, societies moved to the Metaphysical phase.

The "Metaphysical" phase involved the justification of universal rights as being on a higher plane than the authority of any human ruler to countermand, although said rights were not referenced to the sacred beyond mere metaphor. Here, Comte seems to have been an influence for Max Weber's theory of democracy in which societies progress towards freedom. In this Metaphysical stage, Comte regarded the state as dominant, with churchmen and lawyers in control.

The "Scientific" or "Positive" phase came into being after the failure of the revolution and of Napoleon. The purpose of this phase was for people to find solutions to social problems and bring them into force despite the proclamations of "human rights" or prophecy of "the will of God." In this regard, Comte was similar to Karl Marx and Jeremy Bentham. Again, it seems as if Weber co-opted Comte's thinking. Comte saw sociology as the most scientific field and ultimately as a quasi-religious one. In this third stage, which Comte saw as just beginning to emerge, the human race in its entirety becomes the social unit, and government is run by industrial administrators and scientific moral guides.

Karl Marx

Despite his later influence, Karl Marx did not view his work as an ethical or ideological response to nineteenth century capitalism (as most later commentators have). His efforts were, in his mind, based solely on what can be called applied science. Marx saw himself as doing morally neutral sociology and economic theory for the sake of human development. As Christiano states, "Marx did not believe in science for science’s sake…he believed that he was also advancing a theory that would…be a useful tool…[in] effecting a revolutionary upheaval of the capitalist system in favor of socialism."[2] As such, the crux of his argument was that humans are best guided by reason. Religion, Marx held, was a significant hindrance to reason, inherently masking the truth and misguiding followers. As can later be seen, Marx viewed social alienation as the heart of social inequality. The antithesis to this alienation is freedom. Thus, to propagate freedom means to present individuals with the truth and give them a choice as to whether or not to accept or deny it.

Central to Marx's theories was the oppressive economic situation in which he dwelt. With the rise of European industrialism, Marx and his colleague, Engels, witnessed and responded to the growth of what he called "surplus value." Marx’s view of capitalism saw rich capitalists getting richer and their workers getting poorer (the gap, the exploitation, was the "surplus value"). Not only were workers being exploited, but in the process they were being further detached from the products they helped create. By simply selling their work for wages, "workers simultaneously lose connection with the object of labor and become objects themselves. Workers are devalued to the level of a commodity—a thing…" From this objectification comes alienation. The common worker is told he or she is a replaceable tool, alienated to the point of extreme discontent. Here, in Marx’s eyes, religion enters.

As the "opiate of the people," Marx recognized that religion served a true function in society—but did not agree with the foundation of that function. As Marx commentator Norman Birnbaum stated, to Marx, "religion [was] a spiritual response to a condition of alienation." Responding to alienation, Marx thought that religion served to uphold the ideologies and cultural systems that foster oppressive capitalism. Thus, "Religion was conceived to be a powerful conservative force that served to perpetuate the domination of one social class at the expense of others." In other words, religion held together the system that oppressed lower–class individuals. And so, in Marx’s infamous words, "To abolish religion as the illusory happiness of the people is to demand their real happiness. The demand to give up illusions about the existing state of affairs to the demand to give up a state of affairs which needs illusions. The criticism of religion is therefore in embryo the criticism of the vale of tears, the halo of which is religion."[3]

Emile Durkheim

Emile Durkheim placed himself in the positivist tradition, meaning that he thought of his study of society as dispassionate and scientific. He was deeply interested in the problem of what held complex modern societies together. Religion, he argued, was an expression of social cohesion.

In the fieldwork that led to his famous Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Durkheim, who was a highly rational, secular Frenchman himself, spent fifteen years studying what he considered to be "primitive" religion among the Australian aborigines. His underlying interest was to understand the basic forms of religious life for all societies. In Elementary Forms, Durkheim argued that the totemic gods the aborigines worship are actually expressions of their own conceptions of society itself. This is true not only for the aborigines, he argued, but for all societies.

Religion, for Durkheim, is not "imaginary," although he does strip it of what many believers find essential. Religion is very real; it is an expression of society itself, and indeed, there is no society that does not have religion. People perceive as individuals a force greater than themselves, which is social life, and give that perception a supernatural face. Humans then express themselves religiously in groups, which for Durkheim makes the symbolic power greater. Religion is an expression of collective consciousness, which is the fusion of all of individual consciousnesses, which then creates a reality of its own.

It follows, then, that less complex societies, such as the Australian aborigines, have less complex religious systems, involving totems associated with particular clans. The more complex the society, the more complex the religious system. As societies come in contact with other societies, there is a tendency for religious systems to emphasize universalism to a greater and greater extent. However, as the division of labor makes the individual seem more important (a subject that Durkheim treats extensively in his famous Division of Labor in Society), religious systems increasingly focus on individual salvation and conscience.

Durkheim's definition of religion, from Elementary Forms, is as follows:

A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them.[4]

This is a functional definition of religion, meaning that it explains what religion does in social life: Essentially, it unites societies. Durkheim defined religion as a clear distinction between the sacred and the profane, in effect this can be paralleled with the distinction between God and human beings.

This definition also does not stipulate what exactly may be considered sacred. Thus later sociologists of religion (notably Robert Bellah) have extended Durkheimian insights to talk about notions of civil religion, or the religion of a state. American civil religion, for example, might be said to have its own set of sacred "things:" American flags, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., and so forth. Other sociologists have taken Durkheim in the direction of the religion of professional sports, or of rock music.

Max Weber

Max Weber differed from Karl Marx and Emile Durkheim in that he focused his work on the effects of religious action and inaction. Instead of discussing religion as a kind of misapprehension (an "opiate of the people") or as social cohesion, Weber did not attempt to reduce religion to its essence. Instead, he examines how religious ideas and groups interacted with other aspects of social life (notably the economy). In doing so, Weber often attempts to get at religion's subjective meaning to the individual.

In his sociology, Weber uses the German term, Verstehen, to describe his method of interpretation of the intention and context of human action. Weber is not a positivist—in the sense that he does not believe we can find out "facts" in sociology that can be causally linked. Although he believes some generalized statements about social life can be made, he is not interested in hard positivist claims, but instead in linkages and sequences, in historical narratives and particular cases.

Weber argues for making sense of religious action on its own terms. A religious group or individual is influenced by all kinds of things, he says, but if they claim to be acting in the name of religion, one should attempt to understand their perspective on religious grounds first. Weber gives religion credit for shaping a person's image of the world, and this image of the world can affect their view of their interests, and ultimately how they decide to take action.

For Weber, religion is best understood as it responds to the human need for theodicy and soteriology. Human beings are troubled, he says, with the question of theodicy—the question of how the extraordinary power of a divine god may be reconciled with the imperfection of the world that he has created and rules over. People need to know, for example, why there is undeserved good fortune and suffering in the world. Religion offers people soteriological answers, or answers that provide opportunities for salvation—relief from suffering and reassuring meaning. The pursuit of salvation, like the pursuit of wealth, becomes a part of human motivation.

Because religion helps to define motivation, Weber believed that religion (and specifically Protestant Calvinism) actually helped to give rise to modern capitalism, as he asserted in his most famous and controversial work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Capitalism.

In Protestant Ethic, Weber argues that capitalism arose in the West in part because of how the belief in predestination was interpreted by everyday English Puritans. Puritan theology was based on the Calvinist notion that not everyone would be saved; there was only a specific number of the elect who would avoid damnation, and this was based sheerly on God's predetermined will and not on any action you could perform in this life. Official doctrine held that one could not ever really know whether one was among the elect.

Practically, Weber noted, this was difficult psychologically: people were (understandably) anxious to know whether they would be eternally damned or not. Thus, Puritan leaders began assuring members that if they began doing well financially in their businesses, this would be one unofficial sign they had God's approval and were among the saved—but only if they used the fruits of their labor well. This led to the development of rational bookkeeping and the calculated pursuit of financial success beyond what one needed simply to live—and this is the "spirit of capitalism." Over time, the habits associated with the spirit of capitalism lost their religious significance, and rational pursuit of profit became its own aim.

Weber's work on the sociology of religion started with the essay, The Protestant Ethic, but it continued with the analysis of The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism, and Ancient Judaism.

His three main themes were the effect of religious ideas on economic activities, the relation between social stratification and religious ideas, and the distinguishable characteristics of Western civilization. His goal was to find reasons for the different development paths of the cultures of the Occident and the Orient. In the analysis of his findings, Weber maintained that Puritan (and more widely, Protestant) religious ideas had had a major impact on the development of the economic system of Europe and the United States, but noted that they were not the only factors in this development.

In his work, The Religion of China, Weber focused on those aspects of Chinese society that were different from those of Western Europe and especially contrasted with Puritanism, and posed the question, why did capitalism not develop in China?

According to Weber, Confucianism and Puritanism represent two comprehensive but mutually exclusive types of rationalization, each attempting to order human life according to certain ultimate religious beliefs. However, Confucianism aimed at attaining and preserving "a cultured status position" and used it as means of adjustment to the world, education, self-perfection, politeness, and familial piety.

Chinese civilization had no religious prophecy, nor a powerful priestly class. The emperor was the high priest of the state religion and the supreme ruler, but popular cults were also tolerated (however the political ambitions of their priests were curtailed). This forms a sharp contrast with medieval Europe, where the church curbed the power of secular rulers and the same faith was professed by rulers and common folk alike.

In his work on Hinduism, Weber analyzed why Brahmins held the highest place in Indian society. He believed that Indians have ethical pluralism, which differs greatly from the universal morals of Christianity and Confucianism. He also wrote of the the Indian caste system preventing urban status groups. Among Hindus, Weber argued that the caste system stunted economic development as Hindus devalued the material world.

Weber argued that it was the Messianic prophecies in the countries of the Near East, as distinguished from the prophecy of the Asiatic mainland, that prevented the countries of the Occident from following the paths of development marked out by China and India. His next work, Ancient Judaism, was an attempt to prove this theory.

Weber noted that some aspects of Christianity sought to conquer and change the world, rather than withdraw from its imperfections. This fundamental characteristic of Christianity (when compared to Far Eastern religions) stems originally from the ancient Jewish prophecy.

Contemporary sociology of religion

Since the passing of the classical sociologists and the advances of science, views on religion have changed. A new paradigm emerged in the latter part of the twentieth century. Social scientists have begun to attempt to understand religious behavior rather than to discredit it as irrational or ignorant. Acknowledging that science cannot assess the supernatural side of religion, sociologists of religion have come to focus on the observable behaviors and impacts of faith.

Peter Berger formerly argued that the world was becoming increasingly secular, but has since recanted. He has written that pluralism and globalization have changed the experience of faith for individuals around the world as dogmatic religion is now less important than is a personal quest for spirituality.

Rodney Stark has written about rational choice within religion. This theory follows the idea that people will practice the religion that best serves their needs given their personal circumstances. Stark has also argued that the Catholic Church actually spurred rather than retarded science and economics during the Dark Ages.

Christian Smith has detailed the culture behind American evangelism, focusing on the social rather than strictly theological aspects of fundamentalist Christianity.

Robert Bellah wrote of an American "civil religion," which was a patriot faith complete with its own values, rituals, and holidays. Bellah's evidence for his assessment was Americans' use of phrases such as:

- "America is God's chosen nation today."

- "A president's authority…is from God."

- "Social justice cannot only be based on laws; it must also come from religion."

- "God can be known through the experiences of the American people."

- "Holidays like the Fourth of July are religious as well as patriotic."[5]

Bellah says that those with college degrees are less civil religious, while evangelical Christians are likely to be the most civil religious.

In the 1980s, David Bromley wrote about the emergence of cults and brainwashing. He paid particular attention to groups operating counter to these cults and engaging in "deprogramming" or attempting to remove the vestiges of the cult's ideology from the mind of the former member. He compared these activities to the famous American witch hunts in which people were unfairly persecuted for supposed religious deviancy. Similarly, Eileen Barker argued against the idea of brainwashing in the new religious movements that emerged in the late twentieth century. These new religious movements were seen as radical because they did not conform to traditional religious beliefs and for this reason were often accused of being fanatical cults.

Typology of religious groups

According to one common typology among sociologists, religious groups are classified as ecclesias, denominations, cults, or sects. Note that sociologists give these words precise definitions which are different from how they are commonly used. Particularly, the words "cult" and "sect" are used free from negative connotations by sociologists, even though the popular use of these words is often pejorative.

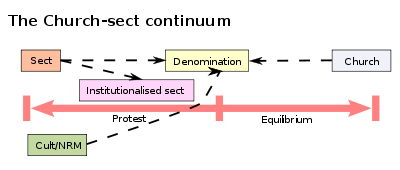

The Church-Sect Typology is one of the most common classification schemes employed in sociology for differentiating between different types of religions. This scheme has its origins in the work of Max Weber. The basic idea is that there is a continuum along which religions fall, ranging from the protest-like orientation of sects to the equilibrium maintaining churches. Along this continuum are several additional types, each of which will be discussed in turn. The term "church" does not necessarily apply to a Christian church, but is intended to signify a well-organized, centralized religion in general.

Church and Ecclesia

The church classification describes religions that are all-embracing of religious expression in a society. Religions of this type are the guardians of religion for all members of the societies in which they are located and tolerate no religious competition. They also strive to provide an all-encompassing worldview for their adherents and are typically enmeshed with the political and economic structures of society.

The classical example of a church is the Roman Catholic Church, especially in the past. Today, the Roman Catholic Church has been forced into the denomination category because of religious pluralism or competition among religions. This is especially true of Catholicism in the United States. The change from a church to a denomination is still underway in many Latin American countries where the majority of citizens remain Catholics.

A slight modification of the church type is that of ecclesia. Ecclesias include the above characteristics of churches with the exception that they are generally less successful at garnering absolute adherence among all of the members of the society and are not the sole religious body. The state churches of some European countries would fit this type.

Denominations

The denomination lies between the church and the sect on the continuum. Denominations come into existence when churches lose their religious monopoly in a society. A denomination is one religion among many. When churches and/or sects become denominations, there are also some changes in their characteristics.

Denominations of religions share many characteristics with one another and often differ on very minor points of theology or ritual. Within Islam, for example, major denominations include Sunni Islam and Shi'a Islam. The difference between the two is mostly political as Sunnis believed that leadership within Islamic communities should be selected from among the most capable. Shiites, on the other hand, believed that leadership should descend directly from the family of the prophet Muhammad. Hindu denominations include Mahayana, Theravada, and Vajrayana. Jewish denominations include Conservative, Hasidic, Humanistic, Karaite, Orthodox, Reconstructionist, and Reform.

Sects

Sects are newly formed religious groups that form to protest elements of their parent religion (generally a denomination). Their motivation tends to be situated in accusations of apostasy or heresy in the parent denomination; they are often decrying liberal trends in denominational development and advocating a return to true religion.

Interestingly, leaders of sectarian movements (the formation of a new sect) tend to come from a lower socio-economic class than the members of the parent denomination, a component of sect development that is not entirely understood. Most scholars believe that when sect formation does involve social class distinctions they involve an attempt to compensate for deficiencies in lower social status. An often seen result of such factors is the incorporation into the theology of the new sect a distaste for the adornments of the wealthy (such as jewelry or other signs of wealth).

After formation, sects take three paths—dissolution, institutionalization, or eventual development into a denomination. If the sect withers in membership, it will dissolve. If the membership increases, the sect is forced to adopt the characteristics of denominations in order to maintain order (bureaucracy, explicit doctrine, and so forth). And even if the membership does not grow or grows slowly, norms will develop to govern group activities and behavior. The development of norms results in a decrease in spontaneity, which is often one of the primary attractions of sects. The adoption of denomination-like characteristics can either turn the sect into a full-blown denomination or, if a conscious effort is made to maintain some of the spontaneity and protest components of sects, an institutionalized sect can result. Institutionalized sects are halfway between sects and denominations on the continuum of religious development. They have a mixture of sect-like and denomination-like characteristics. Examples include: Hutterites and the Amish.

Cults or new religious movements

Cults are, like sects, new religious groups. But, unlike sects, they can form without breaking off from another religious group (though they often do). The characteristic that most distinguishes cults from sects is that they are not advocating a return to pure religion but rather the embracing of something new or something that has been completely lost or forgotten (lost scripture or new prophecy). Cults are also more likely to be led by charismatic leaders than are other religious groups and the charismatic leaders tend to be the individuals who bring forth the new or lost component that is the focal element of the cult (such as The Book of Mormon).

Cults, like sects, often integrate elements of existing religious theologies, but cults tend to create more esoteric theologies from many sources. Cults emphasize the individual and individual peace. Cults also tend to attract the socially disenchanted or unattached (though this isn't always the case.[6] Cults tend to be located in urban centers where they can draw upon large populations for membership. Finally, cults tend to be transitory as they often dissolve upon the death or discrediting of their founder and charismatic leader.

Cults, like sects, can develop into denominations. As cults grow, they bureaucratize and develop many of the characteristics of denominations. Some scholars are hesitant to grant cults denominational status because many cults maintain their more esoteric characteristics (for example, Temple Worship among Mormons). But given their closer semblance to denominations than to the cult type, it is more accurate to describe them as denominations. Some denominations in the U.S. that began as cults include: Mormons or the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Christian Science, and the Nation of Islam.

Finally, it should be noted that there is a push in the social scientific study of religion to begin referring to cults as New Religious Movements or NRMs. The reasoning behind this is because cult has made its way into popular language as a derogatory label rather than as a specific type of religious group. Most religious people would do well to remember the social scientific meaning of the word cult and, in most cases, realize that three of the major world religions originated as cults, including: Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism.

The debate over cults versus religious movements highlights one possible problem for the sociology of religion. This problem is that defining religion is difficult. What is religious to one person may be seen as insane to another and vice versa. This makes developing any rigorous academic framework difficult as common ground is difficult to agree on. This problem also extends to the study of other faiths that are commonly accepted. While a sociologist from a predominantly Christian background may think nothing of the word "God" in the "Pledge of Allegiance" in the United States, someone from a Muslim background could take great interest or even offense at the use. The sensitive and relative nature of religion raises questions of the validity or universality of a field such as the sociology of religion.

Notes

- ↑ Lewis A. Coser, "Auguste Comte: The Law of Human Progress," in Masters of Sociological Thought: Ideas in Historical and Social Context (Harcourt, 1977, ISBN 0155551302), p. 7-8.

- ↑ Kevin J. Christiano, Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments (AltaMira Press, 2002, ISBN 0759100357).

- ↑ Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ↑ Emile Durkheim, Elementary Forms of Religious Life (Free Press, 1995, ISBN 0029079373).

- ↑ William H. Swatos, Encyclopedia of Religion and Society (Rowman Altamira, 1998, ISBN 0761989560), p. 94.

- ↑ James Aho, The Politics of Righteousness: Idaho Christian Patriotism (University of Washington Press, 1995, ISBN 029597494X).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aho, James. The Politics of Righteousness: Idaho Christian Patriotism. University of Washington Press, 1995. ISBN 029597494X.

- Barker, Eileen. New Religious Movements: A Perspective for Understanding Society. Edwin Mellen Press, 1982. ISBN 0889468648.

- Bellah, Robert. The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial. University of Chicago Press, 1992. ISBN 0226041999.

- Berger, Peter L. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Anchor, 1990. ISBN 978-0385073059.

- Bromley, David, and J. Gordon Melton (eds.). Cults, Religion, and Violence. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521668980.

- Christiano, Kevin J. Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments. AltaMira Press, 2002. ISBN 0759100357.

- Coser, Lewis A. Masters of Sociological Thought: Ideas in Historical and Social Context. Harcourt, 1977. ISBN 0155551302.

- Durkheim, Emile. The Division of Labor in Society. The Free Press, 1893. ISBN 0684836386.

- Durkheim, Emile. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. The Free Press, 1915. ISBN 002908010X.

- Marx, Karl. 1844. A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- McGuire, Meredith B. Religion: the Social Context, fifth edition. 2002. ISBN 0-534-54126-7.

- Shupe, Anson, and Jeffrey K. Hadden (eds.). The Politics of Religion and Social Change. Paragon House Publishers, 1988. ISBN 978-0913757772.

- Smith, Christian. The Emergence of Liberation Theology: Radical Religion and Social Movement Theory. University of Chicago Press, 1991. ISBN 0226764109.

- Stark, Rodney. Religion, Deviance, and Social Control. Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415915287.

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0520222021.

- Swatos, William H. Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Rowman Altamira, 1998. ISBN 0761989560.

- Wallis, Roy. "Scientology: Therapeutic Cult to Religious Sect." In Sociology 9(1): 89-100.

- Wallis, Roy. The Road to Total Freedom: A Sociological analysis of Scientology. Columbia University Press, 1976. ISBN 0231042000.

- Weber, Max. The Sociology of Religion, Beacon Press, 1993. ISBN 0807042056.

- Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Los Angeles: Roxbury Company, 2002. ISBN 019532997X.

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2023.

- Sociology of Religion resources on Hartford Institute for Religion Research website

- Religion resources at Center for the Study of Religion and Society

- Verstehen: Max Weber's Homepage

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.