Thomas Paine

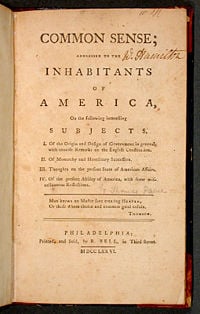

Thomas Paine (January 29, 1737 – June 8, 1809) was an intellectual, scholar, revolutionary, deist and idealist social philosopher. A radical pamphleteer, Paine anticipated and helped foment the American Revolution through his powerful writings, most notably Common Sense, an incendiary pamphlet advocating independence from the kingdom of Great Britain which influenced the [[Declaration of Independence (United States)|Declaration of Independence. His sixteen “Crisis” papers, published between 1776 and 1783, helped to inspire the colonists during the ordeals of the revolution.

Born in England, Paine was an active participant in both the American Revolution and the French Revolution. In Rights of Man, written in reply to Edmund Burke's criticism of the French Revolution, he dismissed monarchy, and viewed all government as, at best, a necessary evil. He opposed slavery and was among the earliest advocates of social security, universal free public education, a guaranteed minimum income, and other programs which are now common practice in many western nations. Paine’s treatise in support of deism, The Age of Reason, won him many enemies among his contemporaries, and in their eyes overshadowed his contributions to democracy. He died alone and unnoticed in New York in 1809.

Life

Paine was born on January 29, 1737, to impoverished parents; Joseph Paine, a (lapsed) Quaker corsetmaker, and Frances Cocke Paine, an Anglican, in Thetford, Norfolk, in eastern England. His younger sister Elizabeth died at seven months. Paine, who grew up around farmers and uneducated people, left school at the age of 12 and, at 13, was apprenticed to his father. In 1756, when the Seven Years’ War between England and France broke out, Paine became a merchant seaman, serving a short time before returning to England in April 1759. There he set up a corset shop in Sandwich, Kent. In September of that year, Paine married Mary Lambert, but his wife died the next year following a move to Margate.

In July 1761, Paine returned to Thetford, where he worked as a supernumerary officer. In December 1762, he became an excise officer in Grantham, Lincolnshire. In August 1764, he was again transferred, this time to Alford, Lincolnshire, at a salary of £50 a year, continuing to study science privately. Documents show that on August 27, 1765, Paine was discharged from his post for claiming to have inspected goods when in fact he had only seen the documentation. On July 3, 1766, he wrote a letter to the Board of Excise asking to be reinstated, and the next day the board granted his request to be assigned to the next vacant post. While waiting for an opening, Paine worked as a corsetmaker in Diss, Norfolk, and later as a servant (records show he worked for a Mr. Noble of Goodman's Fields and then for a Mr. Gardiner at Kensington). He also applied to become an ordained minister of the Church of England, and according to some accounts he preached in Moorfields.

On May 15, 1767, Paine was appointed to a position in Grampound, Cornwall. He was subsequently asked to leave this post to await another vacancy, and he became a schoolteacher in London. On February 19, 1768, Paine was appointed to Lewes, East Sussex, and moved into the room above the fifteenth-century Bull House, a building which held the snuff and tobacco shop of Samuel and Esther Ollive. Paine became involved for the first time in civic matters, after Samuel Ollive introduced him into the Society of Twelve, a local élite group which met twice a year to discuss town issues. In addition, Paine participated in the Vestry, the influential church group that collected taxes and tithes and distributed them to the poor. On March 26, 1771, he married his landlord's daughter, Elizabeth Ollive.

Paine lobbied Parliament for better pay and working conditions for excisemen, and in 1772 published an article, “The Case of the Officers of Excise,” his first political work. In 1774 his petition failed, and Paine was dismissed again from his position as an excise officer. He was impoverished, his goods were auctioned to pay his debts, and in June he separated from his wife. In September 1774, in London, Paine met Benjamin Franklin, who advised him to emigrate to the British colonies in America, and wrote him letters of recommendation.

Paine arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in November 1774, carrying an introduction from Benjamin Franklin. The conflict between the colonists and England was just reaching its height. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, Paine argued that America should not just revolt against taxation, but should demand independence. On January 10, 1776, he published an anonymous pamphlet of 50 pages, “Common Sense,” urging Americans to declare their independence. In just months, the few million inhabitants of the colonies purchased 500,000 copies of the pamphlet, paving the way for the unanimous ratification of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

During the war that followed, Paine served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to General Nathanael Greene. Between 1776 and 1783, he issued sixteen “Crisis” papers, each signed “Common Sense.” “The American Crisis. Number I,” published on December 19, 1776, when George Washington's army was on the verge of disintegration, opened with the flaming words: “These are the times that try men's souls.” Washington ordered the pamphlet read to all the troops at Valley Forge. In 1777 Congress made Paine secretary to the Committee for Foreign Affairs. In 1779 he was forced to resign after he quoted from secret documents to prove that Silas Deane, a member of the Continental Congress, was seeking to profit personally from the aid given to the United States by the French.

The same year, Paine found new employment as clerk of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania. Observing that American troops were desperate because they were not being paid and supplies were scarce, Paine took $500 from his salary and started a subscription for their relief. In 1781 he accompanied John Laurens to France to seek financial support for the army, bringing back money, clothing, and ammunition which were important to the final success of the revolution.

In “Public Good” (1780), Paine called for a national convention to remedy the ineffectual Articles of Confederation and establish a strong central government under “a continental constitution.” At the end of the American Revolution, Paine again found himself impoverished. He had refused to profit from his patriotic writings in order that cheap editions of them might be widely circulated. George Washington endorsed his petition to Congress for financial assistance. In recognition of his services, the state of Pennsylvania gave him £500, and the state of New York gave him a farm in New Rochelle. Paine devoted himself to inventions, registering a patent in Europe for a single-span iron bridge. He developed a smokeless candle, and worked with John Fitch on the early development of steam engines.

French Revolution

In April 1787, Paine left for Europe to promote his plan to build a single-arch bridge across the wide Schuylkill River near Philadelphia. Once in England he was soon diverted from his engineering project. In December 1789, he published an anonymous warning against the attempt of Prime Minister William Pitt to involve England in a war with France over Holland, reminding the British people that war had “but one thing certain and that is increase of taxes.”

Though Paine admired Edmund Burke's support of the American Revolution, Burke’s attack on the uprising of the French people, in Reflections on the Revolution in France, angered him, and he replied immediately with Rights of Man (March 13, 1791). On January 31 he passed the manuscript to the publisher Joseph Johnson, who intended to have it ready for Washington's birthday on February 22. Johnson was visited on a number of occasions by agents of the government, and sensing that Paine's book would be controversial, Johnson decided not to release it on the day it was due to be published. Paine quickly began to negotiate with another publisher, J. S. Jordan. Once a deal was secured, Paine left for Paris on the advice of William Blake, leaving three good friends, William Godwin, Thomas Brand Hollis and Thomas Holcroft, in charge of concluding the publication.

The book appeared on March 13, three weeks later than originally scheduled. An abstract political tract highly critical of monarchies and European social institutions, it immediately created a sensation. At least eight editions were published in 1791, and the work was quickly reprinted in the U.S., where it was widely distributed by the Jeffersonian societies. Rights of Man was so controversial that the British government put Paine on trial in absentia for seditious libel. When Edmund Burke wrote a response, Paine published a second edition, Rights of Man, Part I, (published on February 17, 1792), which contained a plan for the reformation of England, including one of the first proposals for a progressive income tax.

Paine was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, and he was given honorary French citizenship. Despite his inability to speak French, he was elected to the National Convention, representing the district of Pas de Calais. He voted for the French Republic; but argued against the execution of Louis XVI, saying that he should instead be exiled to the United States; he was appreciative of the way royalist France had come to the aid of the American Revolution, and had a moral objection to capital punishment in general and to revenge killings in particular.

Regarded as an ally of the Girondins, he was seen with increasing disfavor by the Montagnards, who were now in power, and in particular by Maximilien Robespierre. A decree was passed at the end of 1793 excluding foreigners from their places in the Convention, and in December 1793, Paine was arrested and imprisoned. Paine protested that he was a citizen of America, which was an ally of Revolutionary France, rather than of Great Britain, which was by that time at war with France. However, Gouverneur Morris, the American ambassador to France, did not defend his claim; Paine thought that George Washington had abandoned him, and quarreled with him for the rest of his life.[1]

Imprisoned and fearing that each day might be his last, Paine apparently escaped execution only by chance. A guard walked through the prison placing a chalk mark on the doors of the prisoners who were due to be condemned that day. He placed a mark on the door of the cell that Paine shared with three other prisoners, which happened to be open at the time. The prisoners in the cell then closed the door so that the chalk mark faced into the cell, were overlooked, and survived the few vital days until they were spared by the fall of Robespierre on July 27, 1794. Paine was released in November 1794, largely because of the new American minister to France, James Monroe.

Prior to his imprisonment, expecting that he might be arrested and executed, Paine wrote the first part of The Age of Reason, an assault on organized "revealed" religion combining a compilation of inconsistencies he found in the Bible with his own advocacy of deism. In his "Autobiographical Interlude" which is found in The Age of Reason between the first and second parts, Paine writes:

Thus far I had written on the 28th of December, 1793. In the evening I went to the Hotel Philadelphia . . . About four in the morning I was awakened by a rapping at my chamber door; when I opened it, I saw a guard and the master of the hotel with them. The guard told me they came to put me under arrestation and to demand the key of my papers. I desired them to walk in, and I would dress myself and go with them immediately.

In the second part of The Age of Reason, Paine writes about his illness and the fever he suffered while imprisoned in the Luxembourg:

. . . I was seized with a fever that in its progress had every symptom of becoming mortal, and from the effects of which I am not recovered. It was then that I remembered with renewed satisfaction, and congratulated myself most sincerely, on having written the former part of The Age of Reason.

Paine published his last great pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, in the winter of 1795-1796. In 1800, Paine purportedly had a meeting with Napoleon I of France, but quickly moved from admiration to condemnation when he saw Napoleon moving towards a dictatorship. Paine remained in France until 1802, when he returned to America on an invitation from Thomas Jefferson.

Last Years

Derided by the public and abandoned by his friends because of his religious views, Paine died at 59 Grove Street in Greenwich Village, New York City, on June 8, 1809. Although the original building is no longer there, the present building has a plaque noting that Paine died at this location. At the time of his death, most American newspapers reprinted the obituary notice from the New York Citizen, which read in part: "He had lived long, did some good and much harm." Only six mourners came to his funeral, two of whom were black, most likely freedmen.

A few years later, the agrarian radical William Cobbett dug up his bones and shipped them back to England. The plan was to give Paine a heroic reburial on his native soil, but the bones were still among Cobbett's effects when he died over 20 years later. There is no confirmed story about what happened to the remains after that, although through the years various people have claimed to own parts of Paine's remains, such as his skull and right hand.

Thought and Works

Paine is remembered today not for the originality of his philosophical thought, but for his ability to articulate ideas clearly and eloquently in a way that motivated his readers to action. Impassioned and outspoken, he became a spokesman for every cause he espoused. Paine was an expert at using printed media to disseminate ideas.

His first political essay, The Case of the Officers of Excise (1772), and his efforts to lobby Parliament for better pay and working conditions for excisemen, cost him his job in 1774.

American Revolution

When Paine arrived in the American colonies in November of 1774, the intentions of the colonists who were rebelling against England were still unclear. The British Parliament had repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, relieving tensions with the colonies, but kept the tax on tea, angering the colonists and resulting in the Boston Tea Party in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1773. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, Paine argued that America should not just revolt against taxation, but should demand independence from England. His pamphlet, Common Sense (January 10, 1776), influenced by the pro-independence writer Benjamin Rush, convinced many colonists, including George Washington, to seek redress in political independence from Great Britain, and was instrumental in bringing about the unanimous ratification of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. It was Paine who proposed the name United States of America for the new nation, in his “Crisis” papers.

During the American Revolutionary War, Paine published a series of 16 pamphlets, The American Crisis, credited with inspiring the early colonists during the ordeal of their long struggle with the British. The first Crisis paper, published on December 23, 1776, and used by George Washington to rally his dispirited troops at Valley Forge, began with these famous words:

These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

Political Liberalism

Some believe Paine may have formed his early views on natural justice while listening to a Puritan mob jeering and attacking those punished in the stocks. Others have argued that he was influenced by his Quaker father.

In The Age of Reason—Paine's treatise in support of deism—he wrote:

The religion that approaches the nearest of all others to true deism, in the moral and benign part thereof, is that professed by the Quakers … though I revere their philanthropy, I cannot help smiling at [their] conceit; … if the taste of a Quaker [had] been consulted at the Creation, what a silent and drab-colored Creation it would have been! Not a flower would have blossomed its gaieties, nor a bird been permitted to sing.

Rights of Man (1791), his response to Edmund Burke’s criticism of the French Revolution, influenced the development of political thought in the formative years of the United States government, and the political reforms which took place in Great Britain. Paine advocated a liberal world view, and suggested a number of ideas which were considered radical in his day. He dismissed monarchy, and viewed all government as, at best, a necessary evil. He opposed slavery and was among the earliest advocates of social security, universal free public education, a guaranteed minimum income, and other programs which are now common practice in many western democracies.

Agrarian Justice, published in the winter of 1795-1796, further developed ideas proposed in the Rights of Man concerning the way in which the institution of land ownership separated the great majority of persons from their rightful natural inheritance and means of independent survival. Paine's proposal is considered to be a form of Basic Income Guarantee. The Social Security Administration of the United States recognizes Agrarian Justice as the first American proposal for an old-age pension.

In advocating the case of the persons thus dispossessed, it is a right, and not a charity… [Government must] create a national fund, out of which there shall be paid to every person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen pounds sterling, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property; And also, the sum of ten pounds per annum, during life, to every person now living, of the age of fifty years, and to all others as they shall arrive at that age. (Thomas Paine, Agrarian Justice)

Paine also published one of the earliest anti-slavery tracts in the colonies, African Slavery in America (1775) and was co-editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine.

The Age of Reason

Though in his early years he was an adherent of the Church of England, in his later years, Paine became highly critical of organized religion and of its role in politics. The Age of Reason (begun in France in 1793), written during the tumult of the French Revolution at a moment when Paine believed his execution was imminent, was intended as “the last offering I shall make to my fellow-citizens of all nations… at a time when the purity of the motive that induced me to it could not admit of a question.” The book systematically criticized of organized religions and many of their doctrines and beliefs, promoted deism as “the one true religion,” and emphasized philosophy and scientific study as the only source of true knowledge.

In the first chapter, Paine stated:

I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life, and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe the equality of man, and I believe that the religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make my fellow creatures happy …. I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

Paine described himself as a “deist” and commented:

How different is [Christianity] to the pure and simple profession of Deism! The true Deist has but one Deity, and his religion consists in contemplating the power, wisdom, and benignity of the Deity in his works, and in endeavoring to imitate him in everything moral, scientifical, and mechanical.

The Age of Reason strongly attacked the doctrines of the Christian church:

The opinions I have advanced… are the effect of the most clear and long-established conviction that the Bible and the Testament are impositions upon the world, that the fall of man, the account of Jesus Christ being the Son of God, and of his dying to appease the wrath of God, and of salvation by that strange means, are all fabulous inventions, dishonorable to the wisdom and power of the Almighty; that the only true religion is Deism, by which I then meant, and mean now, the belief of one God, and an imitation of his moral character, or the practice of what are called moral virtues—and that it was upon this only (so far as religion is concerned) that I rested all my hopes of happiness hereafter. So say I now—and so help me God. (Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason)

The publication of The Age of Reason made many enemies for Paine and overshadowed his services to the American Revolution. His ideological opponents used the book to slander him and discredit his ideas, and several vicious biographies were circulated characterizing him as a drunk, philanderer, thief and tyrant. A popular nursery rhyme of the time said:

- Poor Tom Paine! There he lies,

- Nobody laughs and nobody cries.

- Where he has gone and how he fares,

- Nobody knows and nobody cares.

Legacy

Paine's writings had great influence on his contemporaries, especially the American revolutionaries. John Adams’ prediction that history would attribute the revolution to Paine’s incendiary pamphlets was borne out by Thomas Alva Edison’s The Philosophy of Paine (1925), which remarked that Paine “was the equal of Washington in making America liberty possible. Where Washington performed Paine devised and wrote. The deeds of the one in the Weld were matched by the deeds of the pother with his pen.” His books inspired both philosophical and working-class radicals in the United Kingdom; and he is often claimed as an intellectual ancestor by United States liberals, libertarians, progressives and radicals.

There is a museum in New Rochelle, New York, in Paine’s honor and a statue of him stands in King Street in Thetford, Norfolk, his place of birth. The statue holds a quill and his book, Rights of Man. The book is upside down.

See five statues (Morristown.org. Retrieved March 10, 2007) and read of the: July 4, 1950 statue dedication speech at Morristown, New Jersey.

New York University also has a bust of Paine in its "pantheon of heroes."

See also

Notes

- ↑ Paine, Thomas. The Correspondence of Thomas Paine, To: George Washington, 30 July 1796, On Paine's Service to America (part 1 of 2). The School of Cooperative Individualism. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Collins, Paul. The Trouble with Tom: The Strange Afterlife and Times of Thomas Paine. London: Bloomsbury Books, 2005. ISBN 1582345023

- Conway, Moncure Daniel. The Life of Thomas Paine. G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1892. 2 Volumes. (see e-text in External links)

- Fast, Howard. Citizen Tom Paine (historical novel, 1946). New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce. OCLC 321748

- Keane, John. Tom Paine: A Political Life. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1995.

- Liell, Scott. 46 Pages: Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence. Running Press, 2003. ISBN 0762418133

- Powell, David. Tom Paine, the Greatest Exile. Hutchinson. 1985. ISBN 0312808860

- Paine, Thomas. Collected Writings. Edited by Eric Foner. New York: The Library of America, 1995. ISBN 1883011035

- Paine, Thomas. Common Sense and Other Writings, with Introduction and Notes by Joyce Appleby. New York, Barnes and Noble Classics, 2005. ISBN 978-1593082093

- Van Der Weyde, William. The Life and Works of Thomas Paine (10 Volume Set). Thomas Paine National Historical Association, 1925. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- Russell, Bertrand, "The Fate of Thomas Paine" in Why I Am Not A Christian. Touchstone, 1967. ISBN 0671203231

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Thomas Paine National Historical Association

- Works by Thomas Paine. Project Gutenberg

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.