Urdu

| Urdu اُردو | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | ['ʊrd̪uː] | |

| Spoken in: | India, Pakistan, U.A.E., U.S.A., U.K., Canada, Fiji | |

| Region: | South Asia (Indian subcontinent) | |

| Total speakers: | 61–80 million native 160 million total | |

| Ranking: | 19–21 (native speakers), in a near tie with Italian and Turkish | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Indo-Iranian Indo-Aryan Central zone Urdu | |

| Writing system: | Urdu alphabet (Nasta'liq script) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language of: | ||

| Regulated by: | National Language Authority, National Council for Promotion of Urdu language[1] | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | ur | |

| ISO 639-2: | urd | |

| ISO 639-3: | urd | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Urdu (اردو, trans. Urdū, historically spelled Ordu) is an Indo-Aryan language of the Indo-Iranian branch, belonging to the Indo-European family of languages. It developed under Persian and to a lesser degree Arabic and Turkic influence on apabhramshas (dialects of North India that deviate from the norm of Sanskrit grammar) during the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire (1526–1858 C.E.) in South Asia.

Standard Urdu has approximately the twentieth largest population of native speakers, among all languages. It is the national language of Pakistan, as well as one of the twenty-three official languages of India. Urdu is often contrasted with Hindi, another standardized form of Hindustani. The main differences between the two are that Standard Urdu is conventionally written in Nastaliq calligraphy style of the Perso-Arabic script and draws vocabulary more heavily from Persian and Arabic than Hindi, while Standard Hindi is conventionally written in Devanāgarī and draws vocabulary from Sanskrit comparatively more heavily. Linguists nonetheless consider Urdu and Hindi to be two standardized forms of the same language.

Urdu is a standardized register of Hindustani, termed khaṛībolī, that emerged as a standard dialect.[2] The grammatical description in this article concerns this standard Urdū. The general term "Urdū" can encompass dialects of Hindustani other than the standardized versions.

Speakers and Geographic Distribution

Urdu is spoken in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, UAE, Saudi-Arabia, Mauritius, Canada, Germany, the USA, Iran, Afganistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Maldives, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, South Africa, Oman, Australia, Fiji, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Kenya, Libya, Malawi, Botswana, Ireland and United Kingdom.

There are between 60 and 80 million native speakers of standard Urdu (Khari Boli). Urdu is the tenth most widely spoken language in the world, with 230 million total speakers, including those who speak it as a second language.[3]

Because of Urdu's similarity to Hindi, speakers of the two languages can usually understand one another, if both sides refrain from using specialized vocabulary. Indeed, linguists sometimes count them as being part of the same language diasystem. However, Urdu and Hindi are socio-politically different. People who describe themselves as being speakers of Hindi would question their being counted as native speakers of Urdu, and vice-versa.

In Pakistan, Urdu is spoken and understood by a majority of urban dwellers in such cities as Karachi, Lahore, Rawalpindi/Islamabad, Abbottabad, Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Multan, Peshawar, Gujranwala, Sialkot, Sukkur and Sargodha. Urdu is used as the official language in all provinces of Pakistan. It is also taught as a compulsory language up to high school in both the English and Urdu medium school systems. This has produced millions of Urdu speakers whose mother tongue is one of the regional languages of Pakistan such as Punjabi, Hindku, Sindhi, Pashto, Gujarati, Kashmiri, Balochi, Siraiki, and Brahui. Millions of Pakistanis whose mother tongue is not Urdu can read and write Urdu, but can only speak their mother tongue.

Urdu is the lingua franca of Pakistan and is absorbing many words from regional languages of Pakistan. The regional languages are also being influenced by Urdu vocabulary. Most of the nearly five million Afghan refugees of different ethnic origins (such as Pathan, Tajik, Uzbek, Hazarvi, and Turkmen) who stayed in Pakistan for over twenty-five years have also become fluent in Urdu. A large number of newspapers are published in Urdu in Pakistan, including the Daily Jang, Nawa-i-Waqt, Millat, among many others.

In India, Urdu is spoken in places where there are large Muslim minorities or in cities which were bases for Muslim Empires in the past. These include parts of Uttar Pradesh (namely Lucknow), Delhi, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Mysore, Ajmer, and Ahmedabad. Some Indian schools teach Urdu as a first language and have their own syllabus and exams. Indian madrasahs also teach Arabic, as well as Urdu. India has more than twenty-nine Urdu daily newspapers. Newspapers such as Sahara Urdu Daily Salar, Hindustan Express, Daily Pasban, Siasat Daily, Munsif Daily, and Inqilab are published and distributed in Bangalore, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Mumbai.

Outside South Asia, Urdu is spoken by large numbers of migrant South Asian workers in the major urban centers of the Persian Gulf countries and Saudi Arabia. Urdu is also spoken by large numbers of immigrants and their children in the major urban centers of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Norway, and Australia.

Official status

Urdu is the national language of Pakistan and is spoken and understood throughout the country, where it shares official language status with English. It is used in education, literature, office and court business (it should be noted that in the lower courts in Pakistan, despite the proceedings taking place in Urdu, the documents are in English. In the higher courts, such as the High Courts and the Supreme Court, both the proceedings and documents are in English.), media, and in religious institutions. It holds in itself a repository of the cultural, religious and social heritage of the country.[4] Although English is used in most elite circles, and Punjabi has a plurality of native speakers, Urdu is the lingua franca and is expected to prevail.

Urdu is also one of the officially recognized state languages in India and has official language status in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jammu and Kashmir, and Uttar Pradesh, and the national capital, Delhi. While the government school system in most other states emphasizes Standard Hindi, at universities in cities such as Lucknow, Aligarh, and Hyderabad, Urdu is spoken, learned, and regarded as a language of prestige.

Urdu is a member of the Indo-Aryan family of languages (those languages descending from Sanskrit), which is in turn a branch of the Indo-Iranian group (which comprises the Indo-Aryan and the Iranian branches), which itself is a member of the Indo-European linguistic family. If Hindi and Urdu are considered to be the same language (Hindustani or Hindi-Urdu), then Urdu can be considered to be a part of a dialect continuum which extends across eastern Iran, Afghanistan and modern Pakistan,[5] right into eastern India. These idioms all have similar grammatical structures and share a large portion of their vocabulary. Punjabi, for instance, is very similar to Urdu; Punjabi written in the Shahmukhi script can be understood by speakers of Urdu with little difficulty, but spoken Punjabi has a very different phonology (pronunciation system) and can be harder to understand for Urdu speakers.

Dialects

Urdu has four recognized dialects: Dakhini, Pinjari, Rekhta, and Modern Vernacular Urdu (based on the Khariboli dialect of the Delhi region). Sociolinguists also consider Urdu itself one of the four major variants of the Hindi-Urdu dialect continuum. In recent years, the Urdu spoken in Pakistan has been evolving and has acquired a particularly Pakistani flavor of its own, having absorbed many of that country's indigenous words and proverbs. Many Pakistani speakers of Urdu have begun to emphasize and encourage their own unique form of Urdu to distinguish it from that spoken in India. Linguists point out that the Pakistani dialect of Urdu is gradually being pulled closer to the Iranic branch of the Indo-European family tree, as well as acquiring many local words from Pakistan's several native languages, and is evolving into a distinctive form from that being spoken in India.

Modern Vernacular Urdu is the form of the language that is least widespread and is spoken around Delhi, Lucknow. The Pakistani variant of the language spoken in Karachi and Lahore becomes increasingly divergent from the original form of Urdu, as it loses some of the complicated Persian and Arabic vocabulary used in everyday terms.

Dakhini (also known as Dakani, Deccani, Desia, Mirgan) is spoken in Maharashtra state in India and around Hyderabad and other parts of Andhra Pradesh. It has fewer Persian and Arabic words than standard Urdu. Dakhini is widely spoken in all parts of Karnatka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Urdu is read and written as in other parts of India. A number of daily newspapers and several monthly magazines in Urdu are published in these states.

In addition, Rekhta (or Rekhti), the language of Urdu poetry, is sometimes counted as a separate dialect.

Levels of formality in Urdu

The order of words in Urdu is not as rigidly fixed as it is thought to be by traditional grammarians. Urdu is often called an SOV language (Subject-Object-Verb language), because usually (but not invariably), an Urdu sentence begins with a subject and ends with a verb. However, Urdu speakers or writers enjoy considerable freedom in placing words in an utterance to achieve stylistic effects, see Bhatia and Koul (2000, 34–35).

Urdu in its less formalized register has been referred to as a rekhta (ریختہ, [reːxt̪aː]), meaning "rough mixture." The more formal register of Urdu is sometimes referred to as zabān-e-Urdu-e-mo'alla (زبانِ اردوِ معلہ, [zəba:n e: ʊrd̪uː eː moəllaː]), the "Language of Camp and Court."

The etymology of the words used by a speaker of Urdu determines how polite or refined his speech is. For example, Urdu speakers distinguish between پانی pānī and آب āb, both meaning "water;" or between آدمی ādmi and مرد mard, meaning "man." The former in each set is used colloquially and has older Hindustani origins, while the latter is used formally and poetically, being of Persian origin. If a word is of Persian or Arabic origin, the level of speech is considered to be more formal and grand. Similarly, if Persian or Arabic grammar constructs, such as the izafat, are used in Urdu, the level of speech is also considered more formal and elegant. If a word is inherited from Sanskrit, the level of speech is considered more colloquial and personal.

Politeness

Urdu is supposed to be very subtle, and a host of words are used to show respect and politeness. This emphasis on politeness, which is reflected in the vocabulary, is known as takalluf in Urdu. These words are generally used when addressing elders, or people with whom one is not acquainted. For example, the English pronoun "you" can be translated into three words in Urdu: the singular forms tu (informal, extremely intimate, or derogatory) and tum (informal and showing intimacy called "apna pun" in Urdu) and the plural form āp (formal and respectful). Similarly, verbs, for example, "come," can be translated with degrees of formality in three ways:

- آئے āiye/[aːɪje] or آئیں āen/[aːẽː] ( formal and respectful)

- آو āo/[aːo] (informal and intimate with less degree)

- آ ā/[aː] (extremely informal, intimate and potentially derogatory)

Example in a sher by the poet Daag Dehlvi:

Transliteration

ranj kii jab guftaguu hone lagii

āp se tum tum se tuu hone lagii

Gloss

Grief/distress of when conversation started happening

You(formal) to you(informal), you(informal) to you(intimate) started happening

Vocabulary

Urdu has a vocabulary rich in words with Indian and Middle Eastern origins. The borrowings are dominated by words from Persian and Arabic. There are also a small number of borrowings from Turkish, Portuguese, and more recently English. Many of the words of Arabic origin have different nuances of meaning and usage than they do in Arabic.

The most used word in written Urdu is ka (کا), along with its other variants ki,kay,ko (کی، کے، کو). Though Urdu has borrowed heavily from other languages, its most-used words, including nouns, pronouns, numbers, body parts and many other everyday words, are its own.

Writing System

Nowadays, Urdu is generally written right-to left in an extension of the Persian alphabet, which is itself an extension of the Arabic alphabet. Urdu is associated with the Nasta’liq style of Arabic calligraphy, whereas Arabic is generally written in the modernized Naskh style. Nasta’liq is notoriously difficult to typeset, so Urdu newspapers were hand-written by masters of calligraphy, known as katib or khush-navees, until the late 1980s.

Historically, Urdu was also written in the Kaithi script. A highly-Persianized and technical form of Urdu was the lingua franca of the law courts of the British administration in Bengal, Bihar, and the North-West Provinces and Oudh. Until the late nineteenth century, all proceedings and court transactions in this register of Urdu were written officially in the Persian script. In 1880, Sir Ashley Eden, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, abolished the use of the Persian alphabet in the law courts of Bengal and Bihar and ordered the exclusive use of Kaithi, a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi.[6] Kaithi's association with Urdu and Hindi was ultimately eliminated by the political contest between these languages and their scripts, which resulted in the Persian script being definitively linked to Urdu.

More recently in India, Urdū speakers have adopted Devanagari for publishing Urdu periodicals and have innovated new strategies to mark Urdū in Devanagari as distinct from Hindi in Devanagari.[7] The popular Urdū monthly magazine, महकता आंचल (Mahakta Anchal), is published in Delhi in Devanagari in order to target the generation of Muslim boys and girls who do not know the Persian script. Such publishers have introduced new orthographic features into Devanagari for the purpose of representing Urdū sounds. One example is the use of अ (Devanagari a) with vowel signs to mimic contexts of ع (‘ain). The use of modified Devanagari gives Urdū publishers a greater audience, but helps them to preserve the distinct identity of Urdū.

The Daily Jang was the first Urdu newspaper to be typeset digitally in Nasta’liq by computer. There are efforts underway to develop more sophisticated and user-friendly Urdu support on computers and the Internet. Today, nearly all Urdu newspapers, magazines, journals, and periodicals are composed on computers using various Urdu software programs.

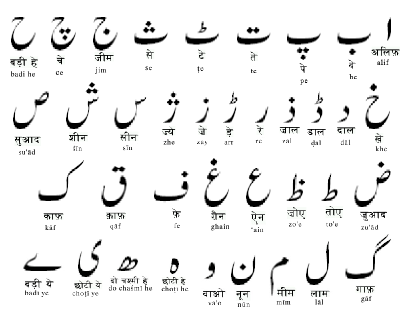

A list of the Urdu alphabet and pronunciation is given below. Urdu contains many historical spellings from Arabic and Persian, and therefore has many irregularities. The Arabic letters yaa and haa are split into two in Urdu: one of the yaa variants is used at the ends of words for the sound [i], and one of the haa variants is used to indicate the aspirated consonants. The retroflex consonants needed to be added as well; this was accomplished by placing a superscript ط (to'e) above the corresponding dental consonants. Several letters which represent distinct consonants in Arabic are conflated in Persian, and this has carried over to Urdu.

| Letter | Name of letter | Pronunciation in the IPA |

|---|---|---|

| ا | alif | [ə, ɑ] after a consonant; silent when initial. Close to an English long "a" as in Mask. |

| ب | bé | [b] English b. |

| پ | pé | [p] English p. |

| ت | té | dental [t̪] Spanish t. |

| ٹ | ṭé | retroflex [ʈ] Close to unaspirated English T. |

| ث | sé | [s] Close to English s |

| ج | jīm | [dʒ] Same as English j |

| چ | cé | [tʃ] Same as English ch, not like Scottish ch |

| ح | baṛī hé | [h] voiceless h |

| خ | khé | [x] Slightly rolled version of Scottish "ch" as in loch |

| د | dāl | dental [d̪] Spanish d. |

| ڈ | ḍāl | retroflex [ɖ] Close to English d. |

| ذ | zāl | [z] English z. |

| ر | ré | dental [r] |

| ڑ | ṛé | retroflex [ɽ] |

| ز | zé | [z] |

| ژ | zhé | [ʒ] |

| س | sīn | [s] |

| ش | shīn | [ʃ] |

| ص | su'ād | [s] |

| ض | zu'ād | [z] |

| ط | to'é | [t] |

| ظ | zo'é | [z] |

| ع | ‘ain | [ɑ] after a consonant; otherwise [ʔ], [ə], or silent. |

| غ | ghain | [ɣ] voiced version of [x] |

| ف | fé | [f] |

| ق | qāf | [q] |

| ک | kāf | [k] |

| گ | gāf | [g] |

| ل | lām | [l] |

| م | mīm | [m] |

| ن | nūn | [n] or a nasal vowel |

| و | vā'o | [v, u, ʊ, o, ow] |

| ہ, ﮩ, ﮨ | choṭī hé | [ɑ] at the end of a word, otherwise [h] or silent |

| ھ | doe cashmī hé | indicates that the preceding consonant is aspirated (p, t, c, k) or murmured (b, d, j, g). |

| ء | hamzah | [ʔ] or silent |

| ی | choṭī yé | [j, i, e, ɛ] |

| ے | baṛī yé | [eː] |

Transliteration

Urdu is occasionally also written in Roman script. Roman Urdu has been used since the days of the British Raj, partly as a result of the availability and low cost of Roman movable type for printing presses. The use of Roman Urdu was common in contexts such as product labels. Today it is regaining popularity among users of text-messaging and Internet services and is developing its own style and conventions. Habib R. Sulemani says, "The younger generation of Urdu-speaking people around the world are using Romanized Urdu on the internet and it has become essential for them, because they use the Internet and English is its language. A person from Islamabad chats with another in Delhi on the Internet only in Roman Urdū. They both speak the same language but with different scripts. Moreover, the younger generation of those who are from the English medium schools or settled in the West, can speak Urdu but can’t write it in the traditional Arabic script and thus Roman Urdu is a blessing for such a population."

Roman Urdū also holds significance among the Christians of North India. Urdū was the dominant native language among Christians of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan in the early part of 1900s and is still used by some people in these Indian states. Roman Urdū was a common way of writing among Indian Christians in these states up to the 1960s. The Bible Society of India publishes Roman Urdū Bibles which were widely sold late into the 1960s (they are still published today). Church songbooks are also common in Roman Urdū. However, the usage of Roman Urdū is declining with the wider use of Hindi and English in these states. The major Hindi-Urdu South Asian film industries, Bollywood and Lollywood, make use of Roman Urdū for their movie titles.

Usually, bare transliterations of Urdu into Roman letters omit many phonemic elements that have no equivalent in English or other languages commonly written in the Latin alphabet. It should be noted that a comprehensive system has emerged with specific notations to signify non-English sounds, but it can only be properly read by someone already familiar with Urdu, Persian, or Arabic for letters such as:ژ خ غ ط ص or ق and Hindi for letters such as ڑ. This script may be found on the Internet, and it allows people who understand the language, but are without knowledge of its written forms, to communicate with each other.

Examples

| English | Urdu | Transliteration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello | السلام علیکم | assalāmu ‘alaikum | lit. "Peace be upon you." اداب [aˈdaːb] would generally be used to give respect و علیکم السلام [ˈwaɭikum ˈaʔsaɭam] is the correct response. |

| Hello | آداب عرض ہے | ādāb arz hai | "Regards to you" (lit "Regards are expressed"), a very formal secular greeting. |

| Good Bye | خدا حافظ | khudā hāfiz | Khuda is Persian for God, and hāfiz is from Arabic hifz "protection." So lit. "May God be your Guardian." Standard and commonly used by Muslims and non-Muslims, or al vida formally spoken all over |

| yes | ہاں | hān | casual |

| yes | جی | jī | formal |

| yes | جی ہاں | jī hān | confident formal |

| no | نا | nā | casual |

| no | نہیں، جی نہیں | nahīn, jī nahīn | formal;jī nahīn is considered more formal |

| please | مہربانی | meharbānī | |

| thank you | شکریہ | shukrīā | |

| Please come in | تشریف لائیے | tashrīf laīe | lit. "Bring your honor" |

| Please have a seat | تشریف رکھیئے | tashrīf rakhīe | lit. "Place your honor" |

| I am happy to meet you | اپ سے مل کر خوشی ہوئی | āp se mil kar khvushī (khushī) hūye | lit. "Meeting you has made me happy" |

| Do you speak English? | کیا اپ انگریزی بولتے ہیں؟ | kya āp angrezī bolte hain? | lit. "Do you speak English?" |

| I do not speak Urdu. | میں اردو نہیں بولتا/بولتی | main urdū nahīn boltā/boltī | boltā is masculine, boltī is feminine |

| My name is ... | میرا نام ۔۔۔ ہے | merā nām .... hai | |

| Which way to Lahore? | لاھور کس طرف ہے؟ | lāhaur kis taraf hai? | |

| Where is Lucknow? | لکھنئو کہاں ہے؟ | lakhnau kahān hai | |

| Urdu is a good language. | اردو اچھی زبان ہے | urdū acchī zubān hai |

Sample text

The following is a sample text in zabān-e urdū-e muʻallā (formal Urdu), of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

Urdu text

- دفعہ 1: تمام انسان آزاد اور حقوق و عزت کے اعتبار سے برابر پیدا ہوۓ ہیں۔ انہیں ضمیر اور عقل ودیعت ہوئی ہی۔ اسلۓ انہیں ایک دوسرے کے ساتھ بھائی چارے کا سلوک کرنا چاہیۓ۔

Transliteration (ALA-LC)

- Dafʻah 1: Tamām insān āzād aur ḥuqūq o ʻizzat ke iʻtibār se barābar paidā hu’e heṇ. Unheṇ z̤amīr aur ʻaql wadīʻat hu’ī he. Isli’e unheṇ ek dūsre ke sāth bhā’ī chāre kā sulūk karnā chāhi’e.

Gloss (word-for-word)

- Article 1: All humans free[,] and rights and dignity *('s) consideration from equal born are. To them conscience and intellect endowed is. Therefore, they one another *('s) brotherhood *('s) treatment do must.

Translation (grammatical)

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Note: *('s) represents a possessive case which when written is preceded by the possessor and followed by the possessed, unlike the English 'of'.

Common difficulties faced in learning Urdu

- The phonetic mechanism of some sounds peculiar to Urdu (for example, ṛ, dh): The distinction between aspirated and unaspirated consonants is difficult for English speakers. The distinction between dental and alveolar (or retroflex) consonants also poses problems. English speakers will find that they need to carefully distinguish between four different d-sounds and four different t-sounds.

- Pronunciation of vowels: In English, unstressed vowels tend to have a "schwa" quality. The pronunciation of such vowels in English is changed to an "uh" sound; this is called reducing a vowel sound. The second syllable of "unify" is pronounced /ə/, not i. The same for the unstressed second syllable of "person" which is also pronounced /ə/ rather than "oh." In Urdu, English-speakers must constantly be careful not to reduce these vowels.

- In this respect, probably the most important mistake would be for English speakers to reduce final "ah" sounds to "uh." This can be especially important because an English pronunciation will lead to misunderstandings about grammar and gender. In Urdu, وہ بولتا ہے voh boltā hai is "he talks" whereas وہ بولتی ہے voh boltī hai is "she talks." A typical English pronunciation in the first sentence would be "voh boltuh hai," which will be understood as "she talks" by most Urdu-native speakers.

- The "a" ending of many gender-masculine words of native origin, due to romanization, is highly confused by non-native speakers, because the short "a" is dropped in Urdu (such as ہونا honā).

- The verbal concordance: Urdu exhibits split ergativity; for example, a special noun ending is used to mark the subject of a transitive verb in the perfect tense, but not in other tenses.

- Relative-correlative constructions: In English interrogative and relative pronouns are the same word. In "Who are you?" the word "who" is an interrogative, or question, pronoun. In "My friend who lives in Sydney can speak Urdu," the word "who" is not an interrogative, or question-pronoun. It is a relative, or linking-pronoun. In Urdu, there are different words for each. The interrogative pronoun tends to start with the "k" sound:" kab = when?, kahān = where?, kitnā = how much? This is similar to the "W" in English, which is used for the same purpose. The relative pronouns are usually very similar but start with "j" sounds: jab = when, jahān = where, jitnā = how much.

Literature

Urdu has only become a literary language in recent centuries, as Persian and Arabic were formerly the idioms of choice for "elevated" subjects. However, despite its late development, Urdu literature boasts some world-recognized artists and a considerable corpus.

Prose

Religious

After Arabic and Persian, Urdu holds the largest collection of works on Islamic literature and Sharia. These include translations and interpretation of Qur'an, commentary on Hadith, Fiqh, history, spirituality, Sufism, and metaphysics. A great number of classical texts from Arabic and Persian, have also been translated into Urdu. Relatively inexpensive publishing, combined with the use of Urdu as a lingua franca among Muslims of South Asia, has meant that Islam-related works in Urdu outnumber such works in any other South Asian language. Popular Islamic books, originally written in Urdu, include Fazail-e-Amal, Bahishti Zewar, the Bahar-e-Shariat.

Literary

Secular prose includes all categories of widely known fiction and non-fiction work, separable into genres. The dāstān, or tale, a traditional story which may have many characters and complex plotting, has now fallen into disuse.

The afsāna, or short story, is probably the best-known genre of Urdu fiction. The best-known afsāna writers, or afsāna nigār, in Urdu are Saadat Hasan Manto, Qurratulain Hyder (Qurat-ul-Ain Haider), Munshi Premchand, Ismat Chughtai, Krishan Chander, Ghulam Abbas, Banu Qudsia, and Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi. Munshi Premchand became known as a pioneer in the afsāna, though some contend that his were not technically the first, as Sir Ross Masood had already written many short stories in Urdu.

Novels form a genre of their own, in the tradition of the English novel. Other genres include saférnāma (odyssey, travel story), mazmoon (essay), sarguzisht, inshaeya, murasela, and khud navvisht (autobiography).

Poetry

Urdu has been the premier language of poetry in South Asia for two centuries, and has developed a rich tradition in a variety of poetic genres. The "Ghazal" in Urdu represents the most popular form of subjective poetry, while the "Nazm" exemplifies the objective kind, often reserved for narrative, descriptive, didactic or satirical purposes. The broad heading of Nazm can include the classical forms of poems known by specific names such as "Masnavi" (a long narrative poem in rhyming couplets on any theme: Romantic, religious, or didactic), "Marsia" (an elegy traditionally meant to commemorate the martyrdom of Hazrat Imam Hussain Alla hiss salam, grandson of Prophet Muhammad Sal lal laho allaha wa allahe wa sallam, and his comrades of the Karbala fame), or "Qasida" (a panegyric written in praise of a king or a nobleman), because all these poems have a single presiding subject, logically developed and concluded. However, these poetic species have an old-world aura about their subject and style, and are different from the modern Nazm, supposed to have come into vogue in the later part of the nineteenth century.

- Diwan (دیوان) A collection of poems by a single author; it may be a "selected works," or the whole body of work.

- Doha (دوہا) A form of self-contained rhyming couplet in poetry.

- Geet (گیت)

- Ghazal (غزل), as practiced by many poets in the Arab tradition. Mir, Ghalib, Momin, Dagh, Jigar Muradabadi, Majrooh Sutanpuri, Faiz, Firaq Gorakhpur,Iqbal, Zauq, Makhdoom, Akbar Ilahabadi, and Seemab Akbarabadi are well-known composers of Ghazal.

- Hamd (حمد) A poem or song in praise of Allah

- Kalam (کلام) Kalam refers to a poet’s total body of poetic work.

- Kulyat (کلیات) A published collection of poetry by one poet.

- Marsia (مرثیہ) An elegiac poem written to commemorate the martyrdom and valor of Hazrat Imam Hussain and his comrades of the Karbala.

- Masnavi (مثنوی) The masnavi consists of an indefinite number of couplets, with the rhyme scheme aa/bb/cc, and so on.

- Musaddas (مسدس) A genre in which each unit consists of 6 lines (misra).

- Mukhammas A type of Persian or Urdu poetry with Sufi connections based on a pentameter. The word mukhammas means "fivefold" or "pentagonal."

- Naat (نعت) Poetry that specifically praises Muhammad.

- Nazm (نظم) Urdu poetic form that is normally written in rhymed verse.

- Noha (نوحہ) a genre of Arabic, Persian, or Urdu prose depicting the martyrdom of Imam Hussein. Strictly speaking noha is the sub-parts of Marsia.

- Qasida (قصیدہ) A form of poetry from pre-Islamic Arabia which typically runs more than 50 lines, and sometimes more than 100. It is often a panegyric written in praise of a king or a nobleman.

- Qat'ã (قطعہ)

- Rubai (also known as Rubayyat or Rubaiyat) (رباعیات) Arabic: رباعیات) (a plural word derived from the root arba'a meaning "four") means "quatrains" in the Persian language. Singular: ruba'i (rubai, ruba'ee, rubayi, rubayee). The rhyme scheme is AABA, that is, lines 1, 2 and 4 rhyme.

- Sehra (سہرا) A poem sung at a wedding in praise of the groom, praying to God for his future wedded life. There are no specifications for a Sehra except that it should rhyme and be of the same meter. Sehras are generally written by individuals praising their brothers, so they are very varied in style and nature.

- Shehr a'ashob

- Soz (سوز) An elegiac poem written to commemorate the martyrdom and valour of Hazrat Imam Hussain and his comrades of the Karbala.

Foreign forms such as the sonnet, azad nazm (also known as Free verse) and haiku have also been used by some modern Urdu poets.

Probably the most widely recited, and memorized genre of contemporary Urdu poetry is nāt—panegyric poetry written in praise of the Prophet Muhammad Sal lal laho allaha wa allahe wa sallam. Nāt can be of any formal category, but is most commonly in the ghazal form. The language used in Urdu nāt ranges from the intensely colloquial to a highly Persianized formal language. The great early twentieth century scholar Imam Ahmad Raza Khan, who wrote many of the most well known nāts in Urdu, epitomized this range in a ghazal of nine stanzas (bayt) in which every stanza contains half a line each of Arabic, Persian, formal Urdu, and colloquial Hindi. The same poet composed a salām—a poem of greeting to the Prophet Muhammad Sal lal laho allaha wa allahe wa sallam, derived from the unorthodox practice of qiyam, or standing, during the mawlid, or celebration of the birth of the Prophet—Mustafā Jān-e Rahmat, which, due to being recited on Fridays in some Urdu speaking mosques throughout the world, is probably one of the more frequently recited Urdu poems of the modern era.

Another important genre of Urdu prose are the poems commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Hussain Allah hiss salam and Battle of Karbala, called noha (نوحہ) and marsia. Anees and Dabeer are famous in this regard.

An Ash'ār (اشعار) (Couplet) consists of two lines, Misra (مصرعہ); the first line is called Misra-e-oola (مصرع اولی) and the second is called 'Misra-e-sānī' (مصرعہ ثانی). Each verse embodies a single thought or subject (sing) She'r (شعر).

Example of Urdu poetry

As in Ghalib's famous couplet where he compares himself to his great predecessor, the master poet Mir:[8]

ریختا کے تم ہی استاد نہیں ہو غالب

کہتے ہیں اگلے زمانے میں کوئی میر بھی تھا

Transliteration

- Rekhta ke tumhin ustād nahīn ho Ghālib

- Kahte hainn agle zamāne meinn ko'ī Mīr bhī thā

Translation

- You are not the only master of poetry O'Ghalib,

- They say, in the past; was also someone Mir

History

Urdu developed as local Indo-Aryan dialects came under the influence of the Muslim courts that ruled South Asia from the early thirteenth century. The official language of the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal Empire, and their successor states, as well as the cultured language of poetry and literature, was Persian, while the language of religion was Arabic. Most of the Sultans and nobility in the Sultanate period were Persianized Turks from Central Asia who spoke Turkish as their mother tongue. The Mughals were also from Persianized Central Asia, but spoke Turkish as their first language; however the Mughals later adopted Persian. Persian became the preferred language of the Muslim elite of north India before the Mughals entered the scene. Babur's mother tongue was Turkish and he wrote exclusively in Turkish. His son and successor Humayun also spoke and wrote in Turkish. Muzaffar Alam, a noted scholar of Mughal and Indo-Persian history, suggests that Persian became the lingua franca of the empire under Akbar for various political and social factors due to its non-sectarian and fluid nature.[9] The mingling of these languages led to a vernacular that is the ancestor of today's Urdu. Dialects of this vernacular are spoken today in cities and villages throughout Pakistan and northern India. Cities with a particularly strong tradition of Urdu include Hyderabad, Karachi, Lucknow, and Lahore.

An alternative theory of the origin of Urdu is that the language was born in Punjab. Hafiz Mehmood Shirani proposed that since Mahmud of Ghazni had conquered Lahore and Muslims stayed there for some 200 years before invading Delhi, Urdu developed during the Ghaznavid period. Shirani argued that some two centuries later Muslim conquerors brought this new language to Delhi with them. To support his argument he noted various similarities between Urdu and Punjabi.[10] Shirani was in fact not the first to reach this conclusion, Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, T. Graham Bailey, and Mohiuddin Qadri Zor had previously expressed similar views, but he was the first to try to prove the theory. However, linguist Masud Husain Khan rejected this theory, publishing his research in Muqaddama-e-tareekh-e-zaban-e-Urdu.[11]

The name Urdu

The term “Urdu” came into use when Shah Jahan built the Red Fort in Delhi. The word Urdu itself comes from a Turkic word ordu, "tent" or "army," from which English also gets the word "horde." Hence Urdu is sometimes called "Lashkarī zabān" or “the language of the army.” Furthermore, armies of India were often composed of soldiers with various native tongues. Hence, Urdu was the language chosen to address the soldiers, as it abridged several languages.

Wherever Muslim soldiers and officials settled, they carried Urdu with them. Urdu enjoyed a commanding status in the literary courts of late Muslim rulers and Nawabs, and flourished under their patronage, partially displacing Persian as the language of elite in the Indian society of that time.

Urdu continued as one of many languages in Northwest India. In 1947, Urdu was established as the national language of Pakistan, in the hope that this move would unite and homogenize the various ethnic groups of the new nation. Urdu suddenly went from the language of a minority to the language of the majority. It also became the official language of some of the various states of India. Today, Urdu is taught throughout Pakistani schools and spoken in government positions, and it is also common in much of Northern India. Urdu's sister language, Hindi, is the official language of India.

Urdu and Hindi

Because of their great similarities of grammar and core vocabularies, many linguists do not distinguish between Hindi and Urdu as separate languages, at least not in reference to the informal spoken registers. For them, ordinary informal Urdu and Hindi can be seen as variants of the same language (Hindustani) with the difference being that Urdu is supplemented with a Perso-Arabic vocabulary and Hindi a Sanskritic vocabulary. Additionally, there is the convention of Urdu being written in Perso-Arabic script, and Hindi in Devanagari. The standard, "proper" grammars of both languages are based on Khariboli grammar, the dialect of the Delhi region. So, with respect to grammar, the languages are mutually intelligible when spoken, and can be thought of as the same language.

Despite their similar grammars, however, Standard Urdu and Standard Hindi are distinct languages in regard to their very different vocabularies, their writing systems, and their political and sociolinguistic connotations. Put simply, in the context of everyday casual speech, Hindi and Urdu can be considered dialects of the same language. In terms of their mutual intelligibility in their formal or "proper" registers, however, they are much less mutually intelligible and can be considered separate languages—they have basically the same grammar but very different vocabularies. There are two fundamental distinctions between them:

- The source of vocabulary (borrowed from Persian or inherited from Sanskrit): In colloquial situations in much of the Indian subcontinent, where neither learned vocabulary nor writing is used, the distinction between the Urdu and Hindi is very small.

- The most important distinction at this level is in the script: if written in the Perso-Arabic script, the language is generally considered to be Urdu, and if written in Devanagari it is generally considered to be Hindi. Since the Partition of India, the formal registers used in education and the media in India have become increasingly divergent from Urdu in their vocabulary. Where there is no colloquial word for a concept, Standard Urdu uses Perso-Arabic vocabulary, while Standard Hindi uses Sanskrit vocabulary. This results in the official languages being heavily Sanskritized or Persianized, and unintelligible to speakers educated in the formal vocabulary of the other standard.

Hindustani is the name often given to the language as it developed over hundreds of years throughout India (which formerly included what is now Pakistan). In the same way that the core vocabulary of English evolved from Old English (Anglo-Saxon) but includes a large number of words borrowed from French and other languages (whose pronunciations often changed naturally so as to become easier for speakers of English to pronounce), what may be called Hindustani can be said to have evolved from Sanskrit while borrowing many Persian and Arabic words over the years, and changing the pronunciations (and often even the meanings) of those words to make them easier for Hindustani speakers to pronounce. Therefore, Hindustani is the language as it evolved organically.

Linguistically speaking, Standard Hindi is a form of colloquial Hindustani, with lesser use of Persian and Arabic loanwords, which inherited its formal vocabulary from Sanskrit; Standard Urdu is also a form of Hindustani, de-Sanskritized, with a significant part of its formal vocabulary consisting of loanwords from Persian and Arabic. The difference is thus in the vocabulary, and not the structure of the language.

The difference is also sociolinguistic: When people speak Hindustani (when they are speaking colloquially), speakers who are Muslims will usually say that they are speaking Urdu, and those who are Hindus will typically say that they are speaking Hindi, even though they are speaking essentially the same language.

The two standardized registers of Hindustani—Hindi and Urdu—have become so entrenched as separate languages that often nationalists, both Muslim and Hindu, claim that Hindi and Urdu have always been separate languages. However, there are unifying forces. For example, it is said that Indian Bollywood films are made in "Hindi," but the language used in most of them is almost the same as that of Urdu speakers. The dialogue is frequently developed in English and later translated to an intentionally neutral Hindustani which can be easily understood by speakers of most North Indian languages, both in India and in Pakistan.

Urdu and Bollywood

The Indian film industry based in Mumbai is often called Bollywood (بالی وڈ). The dialogues in Bollywood movies are written using a vocabulary that could be understood by Urdu and Hindi speakers alike. The film industry wants to reach the largest possible audience, and it cannot do that if the vocabulary of the dialogues is too one-sidedly Sanskritized or Persianized. This rule is broken only for song lyrics, which use elevated, poetic language. Often, this means using poetic Urdu words (of Arabic and Persian origin) or poetic Hindi words (of Sanskrit origin). A few films, like Umrao Jaan, Pakeezah, and Mughal-e-azam, have used vocabulary that leans more towards Urdu, as they depict places and times when Urdu would have been used. Hindi movies that are based on Hindu mythological stories always use Sanskritized Hindi.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, Bollywood films displayed the name of the film in Hindi, Urdu, and Roman scripts. Most Bollywood films today present film titles in the Roman alphabet, although some also include the Devanagari and Nasta`liq scripts.

Dakkhini Urdu

Dakkhini Urdu is a dialect of the Urdu language spoken in the Deccan region of southern India. It is distinct by its mixture of vocabulary from Marathi and Telugu, as well as some vocabulary from Arabic, Persian and Turkish that is not found in the standard dialect of Urdu. In terms of pronunciation, the easiest way to recognize a native speaker is their pronunciation of the letter "qāf" (ﻕ) as "kh" (ﺥ). The majority of people who speak this language are from Bangalore, Hyderabad, Mysore and parts of Chennai. Dakkhin Urdu, mainly spoken by the Muslims living in these areas, can also be divided into two dialects: North Dakkhini, spoken in a wide range from South Maharashtra, Gulbarga and mainly Hyderabad; and South Dakkhini, spoken along Central Karnataka, Bangalore, North Tamil Nadu extending uptil Chennai and Nellore in Andhra Pradesh.

Distinct words, very typical of Dakkhini dialect of Urdu:

Nakko (instead of Nahi in Traditional Urdu) =No

Hau (instead of Han in Traditional Urdu) =Yes

Kaiku (instead of Kyun in Traditional Urdu) =Why

Mereku (North Dakkhini), Manje (South Dakkhin) (instead of Mujhe in Traditional Urdu) = For me

Tereku (North Dakkhini), Tuje (South Dakkhini) (instead of Tujhe in Traditional Urdu) =For you

Notes

- ↑ National Council for Promotion of Urdu language Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ S. Imtiaz Hasnain and K.S. Rajyashree, Hindustani as an Anxiety between Hindi-Urdu Commitment Language in India 3(March 2003). Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ What are the top 200 most spoken languages? Ethnologue, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ Khaver Zia, A Survey of Standardization in Urdu 1999. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ S. Phukan, "The Rustic Beloved: Ecology of Hindi in a Persianate World," The Annual of Urdu Studies 15(5) (2000): 1–30.

- ↑ Christopher R. King, One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India (Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 9780195635652).

- ↑ Rizwan Ahmad, Urdu in Devanagari: Shifting orthographic practices and Muslim identity in Delhi Language in Society 40(3) (June 2011): 259-284.

- ↑ Ghazal 36, Verse 11 Columbia University. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ↑ Muzaffar Alam, The Pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics Modern Asian Studies 32(2) (May 1998): 317–349.

- ↑ Hafiz Mehmood Khan Shirani, Punjab Mein Urdu Internet Archive. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ↑ Web talk held on Prof Masood Husain Khan The Pioneer, October 27, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asher, R. E. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1994. ISBN 0080359434

- Āzād, Muḥammad Ḥusain, Frances W. Pritchett, and Shamsurraḥmān Fārūqī. Āb-e hayāt Shaping the Canon of Urdu Poetry. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0195666348

- Bhatia, Tej K. Colloquial Hindi: The Complete Course for Beginners. New York, NY: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0415110874

- Bhatia, Tej K., and Koul Ashok. Colloquial Urdu: The Complete Course for Beginners. London: Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0415135400

- Chatterji, Suniti K. Indo-Aryan and Hindi. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay, 1960.

- Clyne, Michael (ed.). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3110128551

- Kelkar, A. R. Studies in Hindi-Urdu: Introduction and Word Phonology. Poona: Deccan College, 1968.

- King, Christopher R. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 9780195635652

- Narang, G. C. and D. A. Becker. Aspiration and Nasalization in the Generative Phonology of Hindi-Urdu. Language 47 (1971): 646–767.

- Rai, Amrit. A House Divided: The Origin and Development of Hindi-Hindustani. Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 019561643X

- Sebeok, T. A. (ed.). Current Trends in Linguistics. The Hague: Mouton, 1966.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Languages in India: Urdu Language

- Introductory Urdu (Volume 1)

- Introductory Urdu (Volume 2)

- Platts, John T. (John Thompson). A Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi, and English. London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1884.

- Urdu-English

- UK India: Learn to Read Urdu

| ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.