Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a military conflict in which communist forces of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV or North Vietnam) and the indigenous forces of the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam, (also known as the Việt Cộng) fought against the anti-communist Republic of Vietnam (RVN or South Vietnam) and its allies—most notably the United States—in an effort to unify Vietnam into a single state that would be based on communist ideology.

The chief cause of the war cause was Ho Chi Minh’s desire to establish a single Vietnamese state. Ho viewed the existence of South Vietnam as an ongoing reminder of the era of colonization after Vietnam's struggle for independence from France in the First Indochina War of 1946-1954. Allies of the Vietnamese communists included the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. South Vietnam's main anti-communist ally was the United States, but it also received assistance from South Korea, Australia, Thailand, the Philippines, and New Zealand. The U.S. deployed large numbers of military personnel to South Vietnam. U.S. military advisers first became involved in Vietnam as early as 1950, when they began to assist French colonial forces. In 1956, these advisers assumed full responsibility for training the Army of the Republic of Vietnam or ARVN. President John F. Kennedy made a subtantial increase in the presence of U.S. military advisers to Vietnam prior to his assassination and, under President Lyndon Johnson, large numbers of American combat troops began to arrive in 1965 and the last left the country in 1973.[1] To some degree the Vietnam War was a "proxy war," one of several that erupted during the Cold War period that followed the conclusion of World War II and decolonization.

The Vietnam War was finally concluded on April 30, 1975, with the fall of the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces. The war claimed approximately 2.5 million Southeast Asian lives (including Vietnamese, Laotians, Cambodians and Thais), a large number of whom were civilians. Although it enjoyed a degree of popular support in the early years it became increasingly controversial. The US was widely successful in its military actions in Vietnam but it failed to gain popular support in the States and the war aroused a great deal of opposition in the United States. President Lyndon B. Johnson was unsuccessful in his approach to the war and this led to his decision not to seek reelection in 1968.

Richard Nixon was elected to the presidency in 1968 based upon his claims to have a "secret plan" for a withdrawal from Vietnam with honor. Once in office Nixon implemented a strategy of “Vietnamization” by replacing American with Vietnamese troops. Nixons strategy didn’t continue the Johnson strategy of engagement of the enemy; instead it focused on “pacification”, an initiative aimed at making the widest possible area of South Vietnam safe from Viet Cong activity and it included promoting education and development within those areas. In his book No more Vietnams (1985) Nixon maintained that in 1969, the first year of the implementation of his strategy, an average of four thousand pro-communist military forces a month turned themselves over to the South. Nixon boldly pursued North Vietnamese forces into Cambodia in 1970 amidst great controversy. In 1972 when North Vietnam withdrew from ongoing peace negotiations in Paris at the time of the US Presidential elections, Nixon responded by an extensive bombing of the North in December 1972 that led the North and its allies to return to the negotiations table in Paris in January 1973.

Because of the Watergate scandal Nixon’s popular support continued to dwindle. The Democrat-controlled US Congress cut off all logistical and military support to the South Vietnamese forces. Due to overwhelming popular opposition and damning evidence in the Watergate case Richard Nixon resigned from office in August 1974. Eight months later South Vietnam and Cambodia were communized. In the years immediately following the fall of Vietnam, Laos, Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Capa Verde, Santome e Principe, Grenada, Nicaragua, and Afghanistan were all brought into the Soviet sphere of influence. The United States had surrendered its role as the “world’s policeman”. As has often been observed, the Vietnam War was not lost on the battlefield; it was lost in America’s court of public opinion. It remains a lesson that is relevant for all future conflicts.

History to 1949

From 110 B.C.E. to 938 C.E. much of present-day Vietnam, except for brief periods, was part of China. After gaining independence, Vietnam went through a history of resisting outside aggression. The French gained control of Indochina during a series of colonial wars beginning in the 1840s and lasting through the 1880s. At the post-World War I negotiations that led to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Ho Chí Minh requested that a delegation of Vietnamese be admitted in order to work toward obtaining independence for the Indochinese colonies. His request was rejected, and Indochina's status as a colony of France remained unchanged.

During the Second World War, the government of Vichy France cooperated with Japan, whose forces occupied Indochina. Although the French continued to serve as official administrators until 1944, Japan controlled their three colonies. Ho returned to Vietnam and formed a resistance group to oppose the Japanese in the north, aided by teams deployed by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (the precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency). These teams worked behind enemy lines in Indochina giving support to indigenous resistance groups. In 1944, the Japanese overthrew the French administration and humiliated its colonial officials in front of the Vietnamese population. The Japanese then began to encourage nationalist activity among the Vietnamese and, late in the war, granted Vietnam nominal independence.

After the Japanese surrender, Vietnamese nationalists, communists, and other groups hoped to finally take control of the country. The Japanese army assisted the Viet Minh—Hồ's resistance army—and other Vietnamese independence groups by imprisoning French officials and soldiers and handing over public buildings to the Vietnamese. On September 2, 1945, Ho Chí Minh declared independence from France, proclaiming a new Vietnamese government under his leadership. In his exultant speech before a huge audience in Hanoi, he cited the U.S. Declaration of Independence and a band played "The Star Spangled Banner." Ho, who had been a founding member of the French Communist party in the early 1920’s, anticipated that perhaps the Americans would ally themselves with the Vietnamese nationalist movement. He based this hope on speeches by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who opposed a revival of European colonialism after World War II.

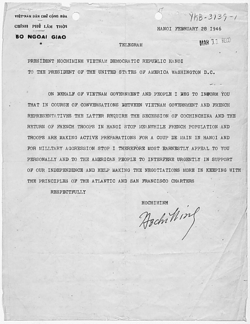

Ho’s rule only lasted a few days, since at the Potsdam Conference the Allies had decided that Vietnam would be jointly occupied by Nationalist Chinese and British forces who would supervise the Japanese surrender and repatriation (Karnow, 163). The Chinese army arrived in Vietnam from the north a few days after Hồ's declaration of independence, taking over areas north of the 16th parallel. The British arrived in the south in October and supervised the surrender and departure of the Japanese army from Indochina. With these actions, the government of Hồ Chí Minh effectively ceased to exist. In the South, the French implored the British to turn control of the region back over to them. Hồ sought international relief from the impending French takeover, including a telegram to President Harry S. Truman, hoping to persuade American intervention.

French officials, when released from Japanese prisons at the end of September 1945, took matters into their own hands in some areas. In the north, the French negotiated with both the Nationalist government of China and the Viet Minh. By agreeing to give up Shanghai and its other concessions in China, the French persuaded the Chinese to allow them to return to northern Vietnam and negotiate with the Viet Minh. Ho agreed to allow French forces to land outside Hanoi, while France agreed to recognize an independent Vietnam within the new French Union. In the meantime, Hồ took advantage of this period of negotiations to liquidate competing nationalist groups in the north. After negotiations with Hồ collapsed over the possibility of his forming a government within the Union in December 1946, the French bombarded Haiphong, killing thousands and then entered Hanoi. Ho and the Việt Minh fled into the mountainous north to begin an insurgency, marking the beginning of the First Indochina War. After the defeat of the Nationalists by the Communists in the Chinese Civil War, Premier Mao Zedong was able to provide direct military assistance to the Viet Minh. By this method, Viet Minh obtained more modern weapons, supplies, and the expertise necessary to transform themselves into a more conventional military force.

Exit of the French, 1950-1955

In the meantime, the U.S. was supplying its French allies with military aid. After the outbreak of the Korean War, the United States began to see what had been a colonial war in Indochina as another example of expansive world-wide communism, directed by the Kremlin. In 1950, the U.S. Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) arrived to screen French requests for aid, advise on strategy, and train Vietnamese soldiers.[2] In 1956, MAAG assumed responsibility for training the Vietnamese army. By 1954, the U.S. had given 300,000 small arms and machine guns, and one billion dollars to support the French military effort and was shouldering at least 80 percent of its cost.[3]

The Viet Minh inflicted a major military defeat against the French at Ðiện Biên Phủ on May 7, 1954. After this, the war lost public support in France and at the Geneva Conference the French government negotiated a peace agreement with the Viet Minh. This allowed the French to leave Indochina and granted all three of its colonies, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam independence. However, Vietnam was temporarily partitioned at the 17th parallel, above which the Viet Minh established a socialist state, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and below which a non-communist state was established under the Emperor Bảo Đại. Bao Dai's Prime Minister, Ngo Dinh Diem, quickly removed him from power, and established himself as President of the new Republic of Vietnam.

The Diem era, 1955-1963

As dictated by the Geneva Accords of 1954, the partition of Vietnam was meant to be temporary, pending free elections for a national leadership. The agreement stipulated that the two military zones, which were separated by a temporary demarcation line (which eventually became the Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ), "should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary," and specifically stated that elections would be held in July of 1956. However, the Diem government refused to enter into negotiations to hold the stipulated elections, encouraged by U.S. unwillingness to allow a certain communist victory in an all-Vietnam election. Questions were also raised about the legitimacy of any election held in the communist-run North. The U.S.-supported government of South Vietnam justified its refusal to comply with the Geneva Accords by virtue of the fact that it had not signed them.

Diem, a devout Roman Catholic, was aloof, closed-minded, and trusted only the members of his immediate family. Vehemently anti-communitist, he was untainted by any connection with the French and he was a natural ally for the U.S. In April and June of 1955, Diem (against U.S. advice) eliminated political opposition by launching military operations against the Cao Dai Sect, the Hoa Hao, and the Binh Xuyen organized crime group (which was allied with the secret police and some army elements).

Later that year, Diem organized an election for president and a legislature, and wrote a constitution. In the election (which he might have won legally) Diem received 98.2 percent of the vote, attracting charges of a rigged election.

Beginning in the summer of 1955, he launched a "Denounce the Communists" campaign, during which communists and other anti-government elements were arrested, imprisoned or executed. During this period refugees and regroupees moved across the demarcation line in both directions. It was estimated that around 52,000 Vietnamese civilians moved from south to north, while 450,000 were air- or boat-lifted from north to south.[4]

As opposition to Diem's rule in South Vietnam grew, low-level insurgency began to take shape in 1957, conducted mainly by Viet Minh cadres who had remained in the south and had hidden caches of weapons in case unification failed to take place through elections. In late 1956, one of the leading communists in the south, Lê Duẩn, returned to Hanoi to urge that the Vietnam Workers' Party take a firmer stand on national reunification, but Hanoi hesitated in launching a full-scale military struggle. In January 1959, under pressure from southern cadres who were being successfully targeted by Diem's secret police, the Central Committee of the Party issued a secret resolution authorizing the use of armed struggle in the South.

On December 12, 1960, under instruction from Hanoi, southern communists established the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam in order to overthrow the government of the south. The NLF was made up of two distinct groups: South Vietnamese intellectuals who opposed the government and were nationalists; and communists who had remained in the south after the partition and regrouping of 1954, as well as those who had since come from the north. While there were many non-communist members of the NLF, they were subject to the control of the party cadres and increasingly side-lined as the conflict continued; they did, however, enable the NLF to portray itself as a broad based, nationalist rather than communist movement.

Coup and assassinations

Some policy-makers in Washington began to believe that Diem was incapable of defeating the communists; some even feared that he might make a deal with Ho Chi Minh. During the summer of 1963, administration officials began discussing the possibility of a regime change in Saigon. The State Department was generally in favor of encouraging a coup while the Pentagon and CIA were more alert to the destabilizing consequences of such a coup and wanted to continue applying pressure to Diem to make political changes.

Chief among the proposed changes was the removal of his younger brother Ngo Dinh Nhu from all of his positions of power. Nhu was in charge of South Vietnam's secret police and was seen as the man behind the Buddhist repression. As Diem's most powerful adviser, Nhu (along with his wife) had become a hated figure in South Vietnam, and one whose continued influence was unacceptable to all members of the Kennedy administration. Eventually, the U.S. State Department, Pentagon, National Security Council, and the CIA determined that Diem was unwilling to further modify his policies and the decision was made to remove U.S. support from the regime. President Kennedy agreed with the consensus.

In November, the U.S. embassy in Saigon communicated through the CIA to the military officers that made up the conspiracy that the U.S. would not oppose Diem's removal. The president was overthrown by the military and later executed along with his brother. After the coup, Kennedy appeared genuinely shocked and dismayed by the murders, although the CIA had anticipated this outcome.

Chaos ensued in the security and defense systems of South Vietnam. Hanoi took advantage of the situation to increase its support for the insurgents in the south. South Vietnam now entered a period of extreme political instability, as one military junta replaced another in quick succession. Ironically, Kennedy was himself assassinated just three weeks after Diệm. Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson, Kennedy's successor, declared on November 24, that the U.S. would continue its support of the South Vietnamese. During this period, the U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam dramatically increased and the "Americanization" of the war began.

The Saigon governments, and their Western allies, portrayed the military action as simply a defense against the use of armed violence to effect political change. At a geopolitical level, the conflict was perceived as a deterrent against expansive global communism emanating from Moscow and Beijing. The Cold War paradigms of containment and the domino theory were in their heyday and framed many of the arguments on the issue of Vietnam. As far as the North Vietnamese and the NLF were concerned, the conflict was a struggle to reunite the nation and to repel foreign aggressors and neo-colonialists—battle cries that were a virtual repeat of those of the war against the French.

Escalation and Americanization, 1963-1968

Gulf of Tonkin and the Westmoreland expansion

On July 27, 1964, 5,000 additional military advisers were ordered to South Vietnam, bringing the total U.S. troop level to 21,000. Shortly thereafter an incident occurred off the coast of North Vietnam that was destined to escalate the conflict to new levels and lead to the full Americanization of the war.

On the evening of August 4, 1964, the destroyer USS Maddox, conducting an electronic intelligence gathering mission four miles off the North Vietnamese coast, was attacked by three torpedo boats of the North Vietnamese navy. Maddox was joined by aircraft from the aircraft-carrier USS Ticonderoga. In the ensuing fire-fight, they damaged two of the Vietnamese boats and disabled another. Joined by the US destroyer, C. Turner Joy, both ships returned to "fly the flag" in what the U.S. claimed were international waters. Early on the 4th, the Maddox reported the presence of hostile boats and believed that an attack might be imminent. Both ships later claimed to have been attacked that evening by North Vietnamese vessels, although it now appears that no such attack actually took place.[5]

There was rampant confusion in Washington, but the incident was seen by the administration as the perfect opportunity to present Congress with "a pre-dated declaration of war." Even before "confirmation" of the phantom attack had been received in Washington, President Johnson decided that an attack could not go unanswered. Just before midnight he appeared on television and announced that retaliatory strikes were underway against North Vietnamese port and oil facilities. Unfortunately, neither Congress nor the American people were going to learn the whole story about the events in the Gulf of Tonkin until the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1969. It was on the basis of the administration's assertions that the attacks were "unprovoked aggression" on the part of North Vietnam, that the U.S. Congress approved the Southeast Asia Resolution (also known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution) on August 7. The law gave the president broad powers to conduct military operations without an actual declaration of war. The resolution passed unanimously in the House of Representatives and was opposed in the Senate by only two members.[6]

Operation Rolling Thunder, 1965-1968

In February 1965, a U.S. air base at Pleiku, in the Central Highlands, was attacked twice by the NLF, resulting in the deaths of over a dozen U.S. personnel. These guerrilla attacks prompted the administration to order retaliatory air strikes (Operation Flaming Dart) against North Vietnam.

Operation Rolling Thunder was the code name given to a sustained strategic bombing campaign targeted against North Vietnam by aircraft of the U.S. Air Force and Navy that began on March 2, 1965. Its original purpose was bolster the morale of the South Vietnamese and to serve as a signaling device to Hanoi. U.S. air power would act as a method of "strategic persuasion," deterring the North politically by the fear of continued or increased bombardment. Rolling Thunder gradually escalated in intensity, with aircraft striking only carefully selected targets. When that did not work, its goals were altered to destroying the will of the North to fight by destroying the nation's industrial base, transportation network, and its (continually increasing) air defenses. After more than a million sorties were flown and three-quarters of a million tons of bombs were dropped, Rolling Thunder ended on November 11, 1968 (Tilford, 1991: 89). Other aerial campaigns (Operation Commando Hunt) were directed to counter the flow of men and supplies down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail.

The big build-up

President Johnson had already appointed General William C. Westmoreland to succeed Paul D. Harkins as Commander of MACV in June 1964. Under Westmoreland, the expansion of American troop strength in Vietnam took place. American forces rose from 16,000 during 1964 to more than 553,000 by 1969. With the U.S. decision to escalate its involvement, ANZUS Pact allies Australia and New Zealand agreed to contribute troops and material to the conflict. They were quickly joined by the Republic of Korea (second only to the Americans in troop strength), Thailand, and the Philippines. The U.S. paid for (through aid dollars) and logistically supplied all of the allied forces. Meanwhile, political affairs in Saigon were finally settling down (at least as far as the Americans were concerned}. On February 14, the most recent military junta, the National Leadership Committee, installed Air Vice-Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky as prime minister. In 1966, the junta selected General Nguyen Van Thieu to run for president with Ky on the ballot as the vice-presidential candidate in the 1967 election. Thieu and Ky were elected. In the presidential election of 1971, Thieu was unopposed. With the installation of the Thieu and Ky government (the Second Republic), the U.S. finally had a legitimate government in Saigon with which to deal.

With the initiation of Rolling Thunder, American airbases and facilities would have to be constructed and manned for the aerial effort. And the defense of those bases would not be entrusted to the South Vietnamese. So, on March 8, 1965, 3,500 United States Marines came ashore at Da Nang as the first U.S. combat troops in South Vietnam, adding to the 25,000 U.S. military advisers already in place. On May 5, the 173d Airborne Brigade became the first U.S. Army ground unit committed to the conflict in South Vietnam. On August 18, Operation Starlite began as the first major U.S. ground operation, destroying a NLF stronghold in Quảng Ngãi Province. The NLF Cong learned from their defeat and subsequently tried to avoid fighting an American-style ground war by reverting to small-unit guerrilla operations.

From late 1964, the North Vietnamese had sent troops to the South. Some officials in Hanoi had favored an immediate invasion of the south, and a plan was developed to use PAVN units to split southern Vietnam in half through the Central Highlands. The two imported adversaries first faced one another during Operation Silver Bayonet, better known as the Battle of the Ia Drang. During the savage fighting that took place, both sides learned lessons. The North Vietnamese, who had suffered heavy casualties, began to adapt to the overwhelming American superiority in air mobility, supporting arms, and close air support. The Americans learned that the Vietnam People's Army (VPA/PAVN) (which was basically a light infantry force) was not a rag-tag band of guerrillas but was a highly-disciplined, well motivated, proficient force.

Search and destroy

On November 27, 1965, the Pentagon declared that if the major operations needed to neutralize North Vietnamese and NLF forces were to succeed, U.S. troop levels in South Vietnam would have to be increased from 120,000 to 400,000. In a series of meetings between Westmoreland and the president held in Honolulu in February 1966, Westmoreland argued that the U.S. presence had succeeded in preventing the immediate defeat of the South Vietnamese government, but that more troops would be necessary if systematic offensive operations were to be conducted.

Acting on this advice, President Johnson authorized an increase in troop strength to 429,000 by August 1966. The large increase in troops enabled MACV to carry out numerous operations that grew in size and complexity during the next two years. For U.S. troops participating in these operations (Masher/White Wing, Attleboro, Cedar Falls, Junction City, and dozens of others) the war consisted of hard marching through difficult terrain and weather that alternated between extreme heat and severe cold. Hours and days passed in excruciating repetition and boredom that was punctuated by adrenaline-pumping minutes of terror when contact was made with the enemy. It was the PAVN/NLF, however, that actually controlled the pace of the war. Fighting only when they believed that they had the upper hand and then disappearing when the Americans and/or ARVN brought their superiority in numbers and firepower to bear. Hanoi, utilizing the Ho Chi Minh and Sihanouk Trails, matched the U.S. at every point of the escalation, funneling manpower and supplies to the southern battlefields. It was indeed a match between the proverbial elephant and the tiger.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail

North Vietnam received foreign military aid shipments through its ports and rail system. This materiel (and PAVN manpower) was then shuttled south down what the Americans called the Ho Chi Minh Trail (the Truong Son Strategic Supply Route to the North Vietnamese). At the end of an arduous journey the men and supplies entered South Vietnam's border areas. Complicating matters, the Trail system ran for most of its length through the neighboring neutral nations of Laos and Cambodia. It was impossible to block the infiltration of men and supplies from the north without bombing or invading those countries. Beginning in December 1964, however, the U.S. began a covert aerial interdiction campaign in Laos that would continue until the end of the conflict in 1973.

Laos and Cambodia also had their own indigenous communist insurgencies to deal with. In Laos, the North Vietnamese-supported Pathet Lao carried on a see-saw struggle with the Royal Lao armed forces. These regular government forces were supported by CIA-sponsored Hmong army of General Vang Pao and by the bombs of the U.S. Air Force. In Cambodia, Prince Norodom Sihanouk maintained a delicate political balancing act both domestically and between eastern and western powers. Believing that the triumph of communism in Vietnam was inevitable, he made a deal with the Chinese in 1965 that allowed North Vietnamese forces to establish permanent bases in his country and to use the port of Sihanoukville for delivery of military supplies in exchange for payments and a proportion of the arms. In the meantime, the Hồ Chí Minh Trail was steadily improved and expanded and became the logistical jugular vein for communist forces fighting in the south.

The Tet Offensive

Late in 1967, Westmoreland said that it was conceivable that in two years or less U.S. forces could be phased out of the war, turning over more and more of the fighting to the ARVN[7]

On January 30, 1968, PAVN and NLF forces broke the truce that accompanied the annual Lunar New Year (Tet) holiday and mounted their largest offensive up to that point in the conflict in hopes of sparking a "General Uprising" among the South Vietnamese. These forces, ranging in size from small groups to entire regiments, attacked nearly every city and major military installation in South Vietnam. The Americans and South Vietnamese, initially surprised by the scope and scale of the offensive, quickly responded and inflicted severe casualties on their enemy (the NLF was essentially eliminated as a fighting force, the places of the dead within its ranks were increasingly filled by North Vietnamese). Although the Communist forces suffered a major setback as a result of this effort the American media portrayed this as a US defeat.

The psychological impact of the Tet Offensive effectively ended the political career of Lyndon Johnson. Shortly thereafter, Senator Robert Kennedy announced his intention to seek the Democratic nomination for the 1968 presidential election. On March 31, in a speech that took America and the world by surprise, Johnson announced that "I shall not seek, and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your president," and pledged himself to devoting the rest of his term in office to the search for peace in Vietnam. Johnson announced that he was limiting bombing of North Vietnam to just north of the DMZ, and that U.S. representatives were prepared to meet with North Vietnamese counterparts in any suitable place "to discuss the means to bring this ugly war to an end." A few days later, much to Johnson's surprise, Hanoi agreed to contacts between the two sides. On May 13, the Paris peace talks began.[8]

Paris peace talks

On October 12, 1967, Secretary of State Dean Rusk had declared that proposals in the U.S. Congress for peace initiatives with Hanoi were futile due to the DRV's repeated refusals to negotiate. The position of Hanoi was simply that the U.S. should evacuate South Vietnam and leave Vietnamese affairs to the Vietnamese. In the wake of the Tet Offensive, Lyndon finally seemed to realize the predicament that his policies had led to. Neither the strategic "carrot and stick" approach of Rolling Thunder nor the attritional stalemate in the ground war had solved the problem in Vietnam. His chief concern then became getting Hanoi to participate in serious negotiations.

U.S. and DRV negotiators met in Paris on May 10, 1968, for the opening session of the peace talks. The DRV delegation was headed by Xuan Thuy, while his American counterpart was U.S. ambassador-at-large Averell Harriman. For five months, however, the negotiations stalled as neither Hanoi nor Washington was willing to make concessions that would allow full negotiations to begin; Hanoi insisted on a total cessation of the bombing of North Vietnam, while Washington demanded a reciprocal de-escalation of North Vietnamese military activities in South Vietnam. Matters were further complicated by the fact that delegations from the NLF and South Vietnamese government would also be participating.

Neither gave way until late in October when Johnson issued preliminary orders to halt the bombing of North Vietnam (which ended on November 11). Johnson's vice-president, and the Democratic Party's nominee in the U.S. presidential election, Hubert H. Humphrey, had managed to close a large lead held by the Republican candidate, Richard M. Nixon, partly by breaking with Johnson in September and calling for an end to the bombing of North Vietnam. Humphrey was further boosted by the apparent breakthrough in Paris. Nixon feared that this lead would be sufficient to give electoral victory to Humphrey. Using an intermediary, Nixon encouraged South Vietnamese President Thieu to stay away from the talks by promising that Saigon would get a better deal under a Nixon presidency. Thieu obliged, and Nixon went on to win the election by a narrow margin. By the time President Johnson left office, about all that had been agreed upon in Paris was the shape of the negotiating table.

Vietnamization and American withdrawal, 1969-1974

Richard Nixon searches for peace with honor

Nixon had continuously campaigned under the slogan that he "had a plan to end the Vietnam War." The goal of the American military effort under Nixon was to buy time, gradually build up the strength of the South Vietnamese armed forces, and to re-equip them with modern weapons so that they could defend their nation on their own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine." As applied to Vietnam, it was labeled "Vietnamization."

One of Nixon's main foreign policy goals had been the achievement of a breakthrough in U.S. relations with China and the Soviet Union. Nixon, whose anti-communist credentials were well established, could make diplomatic overtures to the communists without being accused of being "soft." The result of his overtures was an era of détente that led to nuclear arms reductions by the U.S. and Soviet Union and the beginning of a dialogue with China. In this context, Nixon viewed Vietnam as simply another limited conflict forming part of the larger tapestry of superpower relations; however, he was still doggedly determined to preserve South Vietnam until such time as he could not be blamed for what he saw as its inevitable collapse (or a "descent interval," as it was known). To this end he and his National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger employed Chinese and Soviet foreign policy gambits to successfully defuse some of the anti-war opposition at home and secured movement at the negotiating table in Paris.

To some extent Nixon was successful in convincing the Soviets and the Chinese to reduce their military support for Vietnam. He argued to the Soviets that this would facilitate the strategic arms limitations talks that the Soviet Union sought and he told the Chinese that this would facilitate ending the impasse in US-China relations. However as the Watergate scandal lost Nixon popular support in America Soviet support for Vietnam was renewed.

Operation Menu and the Cambodian incursion, 1969-1970

By 1969, the policy of non-alignment and neutrality had become less appealing to Prince Sihanouk. Due to pressures from the right in Cambodia, he began a shift from the pro-left position he had assumed in 1965-1966. Making overtures for normalized relations with the U.S., he created a Government of National Salvation with the assistance of the pro-American General Lon Nol. Seeing a shift in the prince's position, President Nixon ordered the launching of a top-secret bombing campaign, targeted at the PAVN/NLF Base Areas and sanctuaries along Cambodia's eastern border. The massive B-52 strikes (Operation Menu) deluged Cambodia for 14 months and delivered approximately 2,756,941 tons of bombs, more than the total tonnage that the Allies dropped "during all of World War II, including the bombs that struck Hiroshima and Nagasaki." According to historians Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen, "Cambodia may well be the most heavily bombed country in history."[9]

On March 18, 1970, Sihanouk, who was out of the country on a state visit, was deposed by a vote of the National Assembly and replaced by Lon Nol. Cambodia's ports were immediately closed to North Vietnamese military supplies and the government demanded that the PAVN be removed from the border areas. Taking advantage of the situation, Nixon ordered a military incursion into Cambodia by U.S. and ARVN troops in order to both destroy PAVN/NLF sanctuaries bordering South Vietnam and to buy time for the U.S. withdrawal. During the Cambodian Incursion, U.S. and South Vietnamese forces discovered and removed or destroyed a huge logistical and intelligence haul in Cambodia.

The Cambodian incursion pushed the PAVN deeper into Cambodia, which destabilized the country and forced the North Vietnamese to openly support its despised allies, the Khmer Rouge and allowed them to extend their power. During the incursion, South Vietnamese troops had gone on a rampage, in sharp contrast to the exemplary behavior that had been displayed by the communists, further increasing support for their cause. Sihanouk remained in China, where he established and headed a government in exile, throwing his personal support behind the Khmer Rouge, the North Vietnamese, and the Pathet Lao.

The Easter Offensive

Vietnamization received another severe test in the spring of 1972, when the North Vietnamese launched a massive conventional offensive across the DMZ. Beginning March 30, the Easter Offensive (known as the Nguyen Hue Offensive to the North Vietnamese) quickly overran the three northernmost provinces of South Vietnam, including the provincial capital of Quang Tri City. PAVN forces then drove south toward Hue.

Early in April the PAVN opened two additional operations. The first, a three-division thrust supported by tanks and heavy artillery, came out of Cambodia on April 5. The PAVN seized Loc Ninh and advanced toward the provincial capital of An Loc in Binh Long Province. The second, launched from the tri-border region into the Central Highlands, seized a complex of ARVN outposts near Dak To and then advanced toward Kontum, threatening to split South Vietnam in two.

The U.S. countered with a buildup of American air power to support ARVN defensive operations and to conduct Operation Linebacker, the first bombing of North Vietnam since the bombing halt of 1968. The PAVN attacks against Hue, An Loc, and Kontum were contained and the ARVN launched a counteroffensive in May to retake the lost northern provinces. On September 10, the South Vietnamese flag once again flew over the Citadel of Quang Tri City, but the ARVN offensive then ran out of steam, conceding the rest of the occupied territory to the North Vietnamese. South Vietnam had countered the heaviest attack since Tet, but it was very evident that it was totally dependent on U.S. air power for its survival. Meanwhile, the withdrawal of American troops, who now numbered less than 100,000 at the beginning of the year, was continued as scheduled. By June only six infantry battalions remained. On August 12, the last American ground combat troops left the country.

U.S. presidential election of 1972 and Operation Linebacker II

During the run-up to the 1972 presidential election, the war was again a major issue. The president ended Operation Linebacker on October 22, after an agreement had been reached between the U.S. and North Vietnamese negotiators. The head of the U.S. negotiating team, Henry Kissinger, declared that "peace is at hand" shortly before election day, dealing a death blow to McGovern's already doomed campaign. Kissinger had not, however, counted on the intransigence of South Vietnamese President Thieu, who refused to accept the agreement and demanded some 90 changes. These the North Vietnamese refused to accept, and Nixon was not inclined to put too much pressure on Thieu just before the election, even though his victory was all but assured. The mood between the U.S. and DRV further turned sour when Hanoi went public with the details of the agreement. The Nixon Administration claimed that North Vietnamese negotiators had used the pronouncement as an opportunity to embarrass the president and to weaken the United States. White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler, on November 30, told the press that there would be no more public announcements concerning U.S. troop withdrawals from Vietnam due to the fact that force levels were then down to 27,000.

Due to Thieu's unhappiness with the agreement, primarily the stipulation that North Vietnamese troops could remain "in place" on South Vietnamese soil, the negotiations in Paris stalled as the North Vietnamese refused to accept Thieu's changes, and retaliated with amendments of their own. To reassure Thieu of American resolve, Nixon ordered a massive bombing campaign against North Vietnam using B-52s and tactical aircraft in Operation Linebacker II, which began on December 18, with large raids against both Hanoi and Haiphong. Nixon justified his actions by blaming the impasse in negotiations on the North Vietnamese, causing one commentator to describe his actions as "War by tantrum." Although this heavy bombing campaign caused protests, both domestically and internationally, and despite significant aircraft losses over North Vietnam, Nixon continued the operation until December 29. Nixon also exerted pressure on Thieu to accept the new terms of the agreement.

Return to Paris

On January 15, 1973, citing progress in peace negotiations, Nixon announced the suspension of all offensive actions against North Vietnam, to be followed by a unilateral withdrawal of all U.S. troops. The Paris Peace Accords on "Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam" were signed on January 27, officially ending direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

The agreement called for the withdrawal of all U.S. personnel and an exchange of prisoners of war. Within South Vietnam, a cease-fire was declared (to be overseen by a multi-national, 1,160-man International Control Commission force) and both ARVN and PAVN/NLF forces would remain in control of the areas they then occupied, effectively partitioning South Vietnam. Both sides pledged to work toward a compromise political solution, possibly resulting in a coalition government. In order to maximize the area under their control both sides in South Vietnam almost immediately engaged in land-grabbing military operations, which turned into flashpoints. The signing of the Accords was the main motivation for the awarding of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize to Henry Kissinger and to leading North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho. A separate cease-fire had been installed in Laos in February. Five days before the signing of the agreement in Paris, Lyndon Johnson, under whose leadership America had entered the conflict, died.

The first U.S. prisoners of war were released by North Vietnam on February 11, and all U.S. military personnel were ordered to leave South Vietnam by March 29. As an inducement for Thieu's government to sign the agreement, Nixon had promised that the U.S. would provide financial and limited military support (in the form of air strikes) so that the south could continue to defend itself. But Nixon was fighting for his political life in the growing Watergate Scandal and facing an increasingly hostile Congress that held the power of the purse. The president was able to exert little influence on a hostile public long sick of the Vietnam War.

Nixon was unable to fulfill his promises to Thieu. Economic aid continued (after being cut nearly in half), but most of it was siphoned off by corrupt officials in the South Vietnamese government; little actually went to the military effort. At the same time, aid to North Vietnam from the Soviet Union increased. With the U.S. no longer heavily involved, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union no longer saw the war as significant to their relations. The balance of power shifted decisively in North Vietnam's favor, and the north subsequently launched a major military offensive against the south.

South Vietnam stands alone, 1974 – 1975

Total U.S. withdrawal

In December 1974, the Democratic majority in Congress passed the Foreign Assistance Act of 1974, which cut off all military funding to the South Vietnamese government and made unenforceable the peace terms negotiated by Nixon. Nixon, threatened with impeachment because of Watergate, had resigned his office. Gerald R. Ford, Nixon's vice-president stepped in to finish his term on August 9, 1974. The new president vetoed the Foreign Assistance Act, but his veto was overridden by Congress.

By 1975, the South Vietnamese Army stood alone against the well-organized, highly determined, and foreign-funded North Vietnamese. Within South Vietnam, there was increasing chaos. The withdrawal of the American military had compromised an economy that had thrived largely due to U.S. financial support and the presence of large numbers of U.S. troops. Along with the rest of the non-oil exporting world, South Vietnam suffered economically from the oil price shocks caused by the Arab oil embargo and a subsequent global economic downturn.

Between the signing of the Paris Accord and late 1974 both antagonists had been satisfied with minor land-grabbing operations. The North Vietnamese, however, were growing impatient with the Thieu regime, which remained intransigent as to the called-for national reunification. Hanoi also remained wary that the U.S. would, once again, support its former ally if larger operations were undertaken.

By late 1974, the Politburo in Hanoi gave its permission for a limited VPA offensive out of Cambodia into Phuoc Long Province that would solve a local logistical problem, determine how Saigon forces would react, and determine if the U.S. would indeed return to the fray. In December and January the offensive took place, Phuoc Long Province fell to the VPA, and the American air power did not return. The speed of this success forced the Politburo to reassess the situation. It was decided that operations in the Central highlands would be turned over to General Van Tien Dung and that Pleiku should be seized, if possible. Before he left for the south, General Van was addressed by First Party Secretary Le Duan: "Never have we had military and political conditions so perfect or a strategic advantage so great as we have now."[10]

Campaign 275

On March 10, 1975, the General Dung launched Campaign 275, a limited offensive into the Central Highlands supported by tanks and heavy artillery. The target was Ban Me Thuot, in Darlac Province. If the town could be taken, the provincial capital at Pleiku and the route to the coast would be exposed for a planned campaign in 1976. The ARVN proved no match for the onslaught and its forces collapsed on March 11. Once again, Hanoi was surprised by the speed of their success. Van now urged the Politburo to allow him to seize Pleiku immediately and then turn his attention to Kontum. There would be two months of good campaigning weather until the onset of the monsoon, so why not take advantage of the situation?

President Thieu, fearful that the bulk of his forces would be cut off in the northern provinces and Central Highlands, decided to redeploy those troops southward in what he declared to be a "lighten the top and keep the bottom" strategy. But the withdrawal of the northern forces soon turned into a bloody retreat as the VPA suddenly attacked from the north. While ARVN forces tried to redeploy, splintered elements in the Central Highlands fought desperately against the North Vietnamese. ARVN General Phu abandoned the cities of Pleiku and Kontum and retreated toward the coast in what became known as the "column of tears." As the ARVN retreated, civilian refugees mixed in with them. Due to already-destroyed roads and bridges, Phu's column slowed down as the North Vietnamese closed in. As the exodus staggered down the mountains to the coast, it was shelled incessantly by the VPA and, by April 1, it ceased to exist.

On March 20, Thieu reversed himself and ordered that Hue, Vietnam's third-largest city, be held at all costs. But as the North Vietnamese attacked, panic ensued and ARVN resistance collapsed. On March 22, the VPA opened a siege against Hue. Civilians jammed into the airport and docks hoping for escape. Some even swam into the ocean to reach boats and barges. The ARVN were routed along with the civilians, and some South Vietnamese soldiers shot civilians just to make room for a passageway for their retreat. On March 31, after a three-day fight, Hue fell. As resistance in Hue collapsed, North Vietnamese rockets rained down on Da Nang and its airport. By March 28, 35,000 VPA troops were poised to attack in the suburbs. By the 30th, 100,000 leaderless ARVN troops surrendered as the VPA marched victoriously through Da Nang. With the fall of the city, the defense of the Central Highlands and northern provinces collapsed.

Final North Vietnamese offensive

With the northern half of the country under their control, the Politburo ordered General Van to seize the opportunity for a final offensive against Saigon. The operational plan for the Ho Chi Minh Campaign called for capturing Saigon before May 1, thereby beating the onset of the monsoon and preventing the redeployment and regroupment of ARVN forces to defend the capital. Northern forces, their morale boosted by their recent victories, rolled on, taking Nha Trang, Cam Ranh, and Da Lat.

On April 7, three North Vietnamese divisions attacked Xuan-loc, 40 miles east of Saigon, where they met fierce resistance from the ARVN 18th Infantry Division. For two bloody weeks, severe fighting raged as the ARVN defenders, in a last-ditch effort, tried desperately to save South Vietnam from conquest. By April 21, however, the exhausted garrison had surrendered. A bitter and tearful President Thiệu resigned his office on the same day, declaring that the Americans had betrayed South Vietnam. He left for Taiwan on April 25, leaving control of his doomed nation to General Duong Van Minh. By that time, North Vietnamese tanks had reached Bien Hoa and turned towards Saigon, clashing with occasional isolated ARVN units along the way.

By the end of April, the weakened South Vietnamese military had collapsed on all fronts. On the 27th, 100,000 North Vietnamese troops encircled Saigon, which was defended by only about 30,000 ARVN troops. In order to increase panic and disorder in the city, the VPA began shelling the airport and eventually forced its closure. With the air exit closed, large numbers of civilians who might otherwise have fled the city found that they had no way out. On April 29, the U.S. launched Operation Frequent Wind, arguably the largest helicopter evacuation in history.

Fall of Saigon

Chaos, unrest, and panic ensued as hysterical South Vietnamese officials and civilians scrambled to leave Saigon before it was too late. American helicopters began evacuating both U.S. and South Vietnamese citizens from the U.S. embassy. The evacuations had been delayed until the last possible moment due to U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin's belief that Saigon could be held and that a political settlement was still possible. The evacuations began in an atmosphere of desperation as hysterical crowds of Vietnamese vied for the limited number of seats available on the departing helicopters. Martin pleaded with the U.S. government to send $700 million in emergency aid to South Vietnam in order to bolster the Saigon regime's ability to fight and mobilize fresh military units, but it was to no avail.

In the U.S., South Vietnam was now perceived as doomed. President Ford had given a televised speech on April 23, declaring the end of both the Vietnam War and of all U.S. aid to the Saigon regime. The helicopter evacuations continued day and night as North Vietnamese tanks breached the defenses on the outskirts of the city. In the early morning hours of April 30, the last U.S. Marines evacuated the embassy roof by helicopter as civilians poured over the embassy perimeter and swarmed onto its grounds.

On that day, VPA troops overcame all resistance, quickly capturing the U.S. embassy, the South Vietnamese government army garrison, the police headquarters, radio station, presidential palace, and other vital facilities. The presidential palace was captured and the NLF flag waved victoriously over it. Thieu's successor, President Dương Văn Minh attempted to surrender Saigon, but VPA Colonel Búi Tín informed him that he did not have anything to surrender. Minh then issued his last command, ordering all South Vietnamese troops to lay down their arms.

Aftermath

The last official American military action in Southeast Asia occurred on May 15, 1975, when 18 Marines and airmen were killed during a rescue operation known as the Mayagüez incident involving a skirmish with the Khmer Rouge on an island off the Cambodian coast. The names of those men are listed on the last panel of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

By April 12, the Khmer Rouge had entered the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh. Only hours before their arrival, the U.S. had launched Operation Eagle Pull, an evacuation similar to Frequent Wind. U.S. Ambassador John G. Dean boarded a Marine helicopter and left the city. The communist victory plunged the nation into darkness as the cities and towns were forcibly evacuated, their inhabitants herded into the countryside to begin the construction of a Maoist paradise in Democratic Kampuchea.

Both of the Vietnams were united July 2, 1976, to form the new Socialist Republic of Vietnam and Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City in honor of the former president of North Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands of supporters of the South Vietnamese government were rounded up and sent to reeducation camps. The new regime considered these supporters to be American collaborators and traitors.

North Vietnam followed up its southern victory by first making Laos a virtual puppet state. Socialist fraternalism did not last long. The Khmer Rouge, who had historical territorial ambitions in Vietnam, began a series of border incursions that finally led to a Vietnamese invasion. The VPA onslaught overthrew Pol Pot's murderous regime and a pro-Vietnamese government was installed (see Third Indochina War). The U.S. did not recognize the new government of Cambodia, and, along with the United Nations, continued to consider the Khmer Rouge (perpetrators of the greatest genocide since the Second World War) as their ally. In 1979 the Chinese, furious with the Vietnamese for eliminating their Khmer Rouge allies, launched an invasion of Vietnam's northern provinces. After fighting to a stalemate, the Chinese withdrew.

Other countries' involvement

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union supplied North Vietnam with medical supplies, arms, tanks, planes, helicopters, artillery, ground-air missiles, and other military equipment. As much as 80 percent of all weaponry used by the North Vietnamese side came from the Soviet Union. Hundreds of military advisers were sent to train the Vietnamese army. Soviet pilots acted as training cadre and many have flown combat missions as "volunteers." Fewer than a dozen Soviet citizens lost their lives in this conflict.

People's Republic of China

The People's Republic of China's involvement in the Vietnam War began in the summer of 1962, when Mao Zedong agreed to supply Hanoi with 90,000 rifles and guns free of charge. After the launch of Operation Rolling Thunder, China sent engineering battalions and supporting anti-aircraft units to North Vietnam to repair the damage caused by American bombing, build roads, railroads, and to perform other engineering works. This freed North Vietnamese army units to go to the South. Between 1965 and 1970, over 320,000 Chinese soldiers served in North Vietnam; the peak year was 1967 when 170,000 were serving there. In April 2006, an event was held in Vietnam to honor the almost 1100 Chinese soldiers who were killed in the Vietnam War; a further 4200 were injured.

Republic of Korea

South Korea's military represented the second largest contingent of foreign troops in South Vietnam. South Korea dispatched its first troops beginning in 1964. Large combat battalions began arriving a year later. A total of approximately 300,000 South Korean soldiers were sent to Vietnam. As with the United States, soldiers served one year, and then were replaced with new soldiers, from 1964 until 1973. The maximum number of South Korean troops in Vietnam at any one time was 50,000. More than 5,000 South Koreans were killed and 11,000 were injured in the war.

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

As a result of a decision of the Korean Workers' Party in October 1966, in early 1967, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK/North Korea) sent a fighter squadron to North Vietnam to back up the North Vietnamese 921st and 923rd fighter squadrons defending Hanoi. They stayed through 1968, and 200 pilots were reported to have served.[11] In addition, at least two anti-aircraft artillery regiments were sent as well. North Korea also sent weapons, ammunition and two million sets of uniforms to their comrades in North Vietnam.[12] Kim Il Sung is reported to have told his pilots to "fight in the war as if the Vietnamese sky were their own."

Australia and New Zealand

As U.S. allies under the ANZUS Treaty, Australia and New Zealand sent ground troops to Vietnam. Both nations had gained valuable experience in counterinsurgency and jungle warfare during the Malayan Emergency. Geographically close to Asia, they subscribed to the Domino Theory of communist expansion and felt that their national security would be threatened if communism spread further in Southeast Asia. Australia's peak commitment was 7,672 combat troops, New Zealand's was 552 and most of these soldiers served in the 1st Australian Task Force, based in Phuoc Tuy Province. Australia re-introduced conscription to expand its army in the face of significant public opposition to the war. Like the U.S., Australia began by sending advisers to Vietnam, the number of which rose steadily until 1965, when combat troops were committed. New Zealand began by sending a detachment of engineers and an artillery battery, then started sending special forces and regular infantry. Several Australian and New Zealand units were awarded U.S. unit citations for their service in South Vietnam.

Thailand

Thai Army formations, including the "Queen's Cobra" battalion saw action in South Vietnam between 1965 and 1971. Thai forces saw much more action in the covert war in Laos between 1964 and 1972. There, Thai regular formations were heavily outnumbered by the irregular "volunteers" of the CIA-sponsored Police Aerial Reconnaissance Units or PARU, who carried out reconnaissance activities on the western side of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The activities of these personnel remain one of the great unknown stories of the Southeast Asian conflict.

Canada

Most Canadians who served in the Vietnam War were members of the United States military, with estimated numbers ranging from 2,500 to 3,000. Most became U.S. citizens upon returning from Vietnam or were dual citizens prior to joining the military.[13]

Use of chemical defoliants

One of the most controversial aspects (and certainly the longest lasting in its effects) of the U.S. military effort in Southeast Asia was the wide-spread use of herbicides, which were utilized to remove plant cover from large areas. These chemicals continue to change the landscape, cause diseases, and poison the food-chain in the areas where they were sprayed.

Early in the American effort, the U.S. military decided that, since PAVN/NLF activities were being hidden by triple-canopy jungle and undergrowth, a useful first step might be to "defoliate" areas, especially those surrounding base camps (both large and small) in what became known as Operation Ranch Hand. Corporations like Dow and Monsanto were given the task of developing herbicides for this purpose. The defoliants (which were distributed in drums marked with color-coded bands) included Agent Pink, Agent Green, Agent Purple, Agent Blue, Agent White, and, most famously, the dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange. About 12 million gallons of Agent Orange were sprayed over Southeast Asia during the American commitment. A prime area of Ranch Hand operations was in the Mekong Delta, where the U.S. Navy patrol boats were vulnerable to attack from the undergrowth at the water's edge.

In 1961-1962, the Kennedy administration authorized the use of chemical weapons to destroy rice crops. Between 1961 and 1967, the U.S. Air Force sprayed 20 million U.S. gallons (76,000 m³) of concentrated herbicides over 6 million acres (24,000 km²) of crops and trees, affecting an estimated 13 percent of South Vietnam's land. In 1997, an article published by the Wall Street Journal reported that up to half a million children were born with dioxin-related deformities, and that the birth defects in southern Vietnam were fourfold those in the north. The use of chemical defoliants may have been contrary to international rules of war at the time. A 1967 study by the Agronomy Section of the Japanese Science Council concluded that 3.8 million acres (15,000 km²) of foliage had been destroyed, possibly also leading to the deaths of 1,000 peasants and 13,000 pieces of livestock.

As of 2006, the Vietnamese government estimates that there are over 4,000,000 victims of dioxin poisoning in Vietnam, although the United States government denies any conclusive scientific links between Agent Orange and the Vietnamese victims of dioxin poisoning. In some areas of southern Vietnam, dioxin levels remain at over 100 times the accepted international standard.[14]

The U.S. Veterans Administration has listed prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, type II diabetes, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, peripheral neuropathy, and spina bifida in children of veterans exposed to Agent Orange as possible side effects of their parent's exposure to the herbicides. Although there has been much discussion over whether the use of these defoliants constituted a violation of the laws of war, it must be noted that the defoliants were not considered weapons, since exposure to them did not lead to immediate death or even incapacitation.

Notes

Casualties

The actual numbers of people killed in the conflict remains uncertain. Published statistics vary and do not include all civilian casualties or those of the various irregular forces involved, or victims of the civil war in Cambodia. The following statistics are from Summers (1985): U.S. military fatalities, including missing in action, 57,690; South Vietnamese military, 243,748; Australia and New Zealand military, 469; The Vietnamese Peoples' Army and NLF, 666,000; South Vietnamese civilians, 300,000; North Vietnamese civilians, 65,000.

Names for the conflict

Various names have been applied to the conflict and these have shifted over time, although Vietnam War is the most commonly used title in English. It has been variously called the Second Indochina War, the Vietnam Conflict, the Vietnam War, and, in Vietnamese, Chiến tranh Việt Nam (The Vietnam War) or Kháng chiến chống Mỹ (Resistance War Against America).

- Second Indochina War: places the conflict into context with other distinctive, but related, and contiguous conflicts in Southeast Asia. Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia are seen as the battlegrounds of a larger Indochinese conflict that began at the end of World War II and lasted until communist victory in 1975. This conflict can be viewed in terms of the demise of colonialism and its after-effects during the Cold War.

- Vietnam Conflict: largely a U.S. designation, it acknowledges that the U.S. Congress never declared war on North Vietnam. Legally, the President used his constitutional discretion—supplemented by supportive resolutions in Congress—to conduct what was said to be a "police action."

- Vietnam War: the most commonly-used designation in English, it suggests that the location of the war was exclusively within the borders of North and South Vietnam, failing to recognize its wider context.

- Resistance War Against the Americans to Save the Nation: the term favored by North Vietnam (and after North Vietnam's victory over South Vietnam, by Vietnam as a whole); it is more of a slogan than a name, and its meaning is self-evident. Its usage has been abolished in recent years as the communist government of Vietnam seeks better relations with the United States. Official Vietnamese publications now refer to the conflict generically as "Chiến tranh Việt Nam" (Vietnam War).

Footnotes

- ↑ Herring, America's Longest War

- ↑ George C. Herring, "America's Longest War," p.18

- ↑ Zinn, "A People's History of the United States," p. 471

- ↑ John Prados, "The Numbers Game: How Many Vietnamese Fled South In 1954?" The VVA Veteran, January/February 2005; Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Robert McNamara, et al, 1999, pp. 166-167

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The New York Times, "The Wobble on the War on Capitol Hill," Dec 17, 1967

- ↑ R. K. Brigham, Guerrilla Diplomacy: the NLF's foreign relations and the Vietnam War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998). ISBN 9780801433177

- ↑ Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen, Bombs Over Cambodia. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Clark Dougan, David Fulgham, et al, The Fall of the South (Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1985): 22. ISBN 9780939526161

- ↑ Asia Times Online, Missiles and Madness. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Merle Pribbenow, "The 'Ology War: technology and ideology in the defense of Hanoi, 1967" Journal of Military History 67:1 (2003) p. 183

- ↑ Illuminations, Canadians in Vietnam. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Anthony Failoa, "In Vietnam, Old Foes Take Aim at War's Toxic Legacy" Washington Post. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

Sources

- Anderson, David L. Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War. New York: Columbia University Press, c2002. ISBN 0231114931

- Duiker, William J. The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0813385873

- Herring, George C. America's Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975. Boston: McGraw-Hill, c2002. ISBN 0072417552

- Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. New York: Viking, 1991. ISBN 0140145338

- Kutler, Stanley, ed. Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. New York: Macmillan Library Reference USA, c1997. ISBN 0684805227

- Lewy, Guenter. America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 0195023919

- McMahon, Robert J., ed. Major Problems in the History of the Vietnam War: Documents and Essays. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, c2003. ISBN 061819312X

- McNamara, Robert S., James G. Blight and Robert K. Brigham. Argument Without End: In Search of Answers to the Vietnam Tragedy. New York: Public Affairs, c1999. ISBN 1891620223

- Moise, Edwin E. Historical Dictionary of the Vietnam War. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2001. ISBN 0810841835

- Moyar, Mark. Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521869110

- Palmer, Bruce. The Twenty-Five Year War. New York: Da Capo Press, 1990, c1984. ISBN 0306803836

- Parker, F. Charles IV. Vietnam: Strategy for a Stalemate. New York: Paragon House, 1989. ISBN 0887020410

- Schoenbrun, David. America Inside Out. New York: McGraw-Hill, c1984. ISBN 0070554730

- Schulzinger, Robert D. A Time for War: The United States and Vietnam, 1941-1975. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195071891

- Spector, Ronald. After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. New York: Vintage Books, 1994. ISBN 0679750460

- Summers, Harry G. The Vitenam War Almanack. New York: Facts on File, c1990. ISBN 0816017379

- Tucker, Spencer. ed. Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War : A Political, Social, and Military History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195135245

Primary sources

- Gold, Susan Dudley. The Pentagon Papers : National Security or the Right to Know. New York: Benchmark Books, c2004 ISBN 0761418431

- O'Connell, Kim A. Primary Source Accounts of the Vietnam War. Berkeley Heights, NJ: MyReportLinks.com Books, c2006. ISBN 1598450018

- McCain, John and Mark Salter. Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir. New York: HarperPerennial, 2000. ISBN 0060957867

- Marshall, Kathryn. In the Combat Zone: An Oral History of American Women in Vietnam, 1966-1975. Boston: Little, Brown, c1987. ISBN 0316547077

- Myers, Thomas. Walking Point: American Narratives of Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0195053516

- Neel, Spurgeon Hart.Medical Support of the U.S. Army in Vietnam, 1965-1970. Washington, Dept. of the Army, 1973.

- Tang, Nhu Truong. A Vietcong Memoir. New York: Vintage Books, 1986, c1985. ISBN 0394743091

- Terry, Wallace, ed. Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans. New York: Ballantine Books, c1992. ISBN 0345376668

- Sheehan, Neil, ed. The Pentagon Papers as Published by the New York Times. New York: Quadrangle Books, 1971.

- U.S. Department of State. Foreign Relations of the United States (multivolume collection of official secret documents) vol 1: 1964; vol 2: 1965; vol 3: 1965; vol 4: 1966;

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.