Igloo

- Quinzhee redirects here.

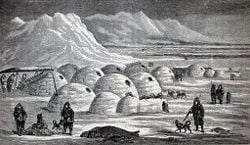

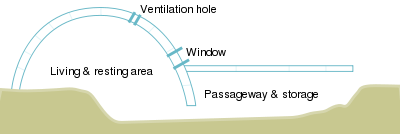

The igloo or iglu is the traditional shelter of Inuit living in the far northern regions. They are built of blocks of snow in a circular form in which the walls curve inward toward the top to form a snow vault in which the arched ceiling is self-supporting. An outstanding example of human ingenuity and adaptability to the environment, the igloo retains heat and protects against wind, since snow and ice act as excellent insulation. The design includes a tunnel entrance that forms a cold trap to preserve heat inside. The sleeping and sitting area is raised above this and so maintains a higher temperature; a small hole near the top of the igloo provides ventilation.

A similar construction is the quinzhee, which is a shelter made by hollowing out a pile of settled snow, and is only for temporary use. In contemporary times this type of snow shelter has become popular among those who enjoy winter camping as well as in survival situations.

Some contemporary Inuit continue to use igloos, especially as temporary shelters while hunting. However, the warming climate of the early twenty-first century reduced the availability of appropriate snow for igloo construction. Although the traditional art of igloo construction by Inuit natives may have declined, the igloo and variations upon it, such as ice hotels, have gained in popularity among those who enjoy the winter experience.

Origin

An igloo (Inuit language: iglu, Inuktitut syllabics: ᐃᒡᓗ, "house," plural: iglooit or igluit, but in English commonly "igloos"), translated sometimes as "snowhouse," is the Inuit word for house or habitation. As such, the Inuit do not restrict the use of this term exclusively to snow houses but include traditional tents, sod houses, homes constructed of driftwood, and modern buildings.[1][2]

The Igluvijaq (ᐃᒡᓗᕕᔭᖅ) refers specifically to the snowhouse.[3] This is a shelter constructed from blocks of snow, generally in the form of a dome. Such igloos were predominantly constructed by people of Canada's Central Arctic and Greenland's Thule area. Other Inuit people used snow to insulate their houses, which were constructed of whalebone and hides.

Although the origin of the igloo may have been lost in antiquity, it is known that Inuit have constructed igloos for hundreds of years. Martin Frobisher, in his expeditions to discover the Northwest Passage landed on Baffin Island in 1576, where he encountered an Inuit igloo village.

Living in an area where snow and ice predominate, particularly in the long dark winter above the Arctic Circle, the igloo is the perfect shelter. Snow is used because the air pockets trapped in it make it an excellent insulator. On the outside, temperatures may be as low as −45 °C (−49.0 °F), but on the inside of an igloo the temperature may range from −7 °C (19 °F) to 16 °C (61 °F) when warmed by body heat alone.[4] A highly functional shelter, the igloo is also aesthetically pleasing; its shape is both strong and beautiful.

Construction

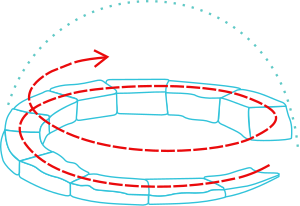

Architecturally, the igloo is unique in that it is a dome that can be raised out of independent blocks leaning on each other and polished to fit without an additional supporting structure during construction. The igloo is not hemispheric but rather shaped like an egg. For a large igloo the first rows of snow blocks form vertical walls, but the key feature of the structure is the spiral form that results from the use of wedge-shaped blocks. From that point, a continuous upward spiral produces a self-supporting dome.[5]

The snow used to build an igloo must have sufficient structural strength to be cut and stacked in the appropriate manner. The best snow to use for this purpose is snow which has been blown by wind, which can serve to compact and interlock the ice crystals. The igloo "is essentially the product of a treeless zone where the unbroken force of the wind so compacts the surface of the snow that it can be carved into building blocks."[6]

The igloo, if correctly built, will support the weight of a person standing on the roof. In the traditional Inuit igloo, the heat from the kulliq (stone lamp) causes the interior to melt slightly. This melting and refreezing builds up an ice sheet and contributes to the strength of the igloo.[5] Thus, the igloo becomes a house of ice rather than snow:

The transformation gives it a remarkable stability; a man can stand on the summit without causing its collapse, and half the house can be destroyed without destroying the other half.[6]

The hole left in the snow where the blocks are cut from is usually used as the lower half of the shelter. The sleeping platform is thus a raised area compared to where one enters the igloo. Because warmer air rises and cooler air settles, the entrance area acts as a cold trap whereas the sleeping area holds whatever heat is generated by a stove, lamp, or body heat. A single block of ice may be inserted to allow light into the igloo. Sometimes, a short tunnel is constructed at the entrance to reduce wind and heat loss when the door is opened. Due to snow's excellent insulating properties, inhabited igloos are surprisingly warm inside. Covers of caribou fur are quite sufficient to keep a person comfortable while sleeping.

The 1922 documentary, Nanook of the North, contains the oldest surviving movie footage of an Inuit constructing an igloo. In the film, "Nanook" builds a large family igloo as well as a smaller igloo for sled pups. He demonstrates the use of an knife made of walrus ivory to cut and trim snow block, as well as the use of clear ice for a window. His igloo was built in about one hour, and was large enough for five people. The igloo was cross-sectioned for film-making, so interior shots could be made.

Use

There are three types of igloo, of different sizes and used for different purposes.

The smallest igloo is constructed as a temporary shelter. Hunters while out on the land or sea ice may camp in one of these iglooit for one or two nights.

Next in size is the semi-permanent, intermediate sized family dwelling. Inuit usually created single room dwellings to housed one or two families. Often there were several of these in a small area, which formed an "Inuit village."

The largest of the igloos was normally built in groups of two. One of the buildings was a temporary building constructed for special occasions; the other was built near by for living. This was constructed either by enlarging a smaller igloo or building from scratch. These could have up to five rooms and housed up to 20 people. A large igloo may have been constructed from several smaller igloos attached by their tunnels giving a common access to the outside. These were used to hold community feasts and traditional dances.

Variations

Linings

The Central Inuit, especially those around the Davis Strait, lined the living area of their igloos with animal skin, which could increase the temperature within from around 2 °C (36 °F) to 10-20 °C (50-68 °F).

Quinzhee

A quinzhee or quinzee (IPA: /ˈkwɪnzi/) is a shelter made by hollowing out a pile of settled snow, and is only for temporary use. This is in contrast to an igloo, which is made from blocks of snow and can be semi-permanent. The word quinzhee is of Athabaskan origin.[7]

The snow for a quinzhee need not be of the same quality as required for an igloo. Quinzhees are not usually meant as a form of permanent shelter, while igloos can be used for seasonal and year round habitation. The construction of a quinzhee is slightly easier than the construction of an igloo, although the overall result is somewhat less sturdy and more prone to collapsing in harsh weather conditions. Quinzhees are normally constructed in times of necessity, usually as an instrument of survival, so aesthetic and long-term dwelling considerations are normally exchanged for economy of time and materials.

Contemporary variations

Although some contemporary Inuit continue to use igloos, especially as temporary shelters while hunting, the warming climate of the early twenty-first century has reduced the availability of appropriate snow for igloo construction. The area within the Artic Circle has warmed considerably, resulting in difficulty in finding snow of the right consistency and in freezing the blocks together.[5]

Nevertheless, although the traditional art of igloo construction by Inuit natives may have declined, the igloo and variations upon it have gained in popularity among those who enjoy the winter experience.

Winter camping and survival

For fun, or for winter camping and survival purposes, it is possible to construct a quinzhee snow shelter by gathering a large pile of snow and excavating the inside. Basically, the procedure involves creating a mound of snow, letting it harden to gain strength, and then digging into it from below and hollowing it out.

The area where the quinzhee is to be constructed must first be flattened. To prevent a situation where there are two different levels of setness, which can cause collapse during excavations, a new snow pile must be made rather than using a natural pile such as a snow drift. After piling the snow to the desired height (usually 6 feet (1.8 m) to 10 feet (3.0 m)) the site should be left for several hours, possibly overnight, while the snow sets. Before excavating sticks are inserted into the roof and wall, approximately 10 inches (250 mm) to 12 inches (300 mm) deep, to be used as a guide when digging out the interior. When digging out is is essential that there be at least one person outside the pile to ensure that no-one is trapped inside if the snow pile collapses. When the interior has been dug out, one or more small air vents should be made, and then a lantern can be used to heat up the inside.

There are several cautions in using a quinzhee. The snow pile can collapse, and it is generally impossible to dig oneself out from the heavy snow. After construction it is safe to sleep in, but not strong enough to hold significant weight on top.

Igloo hotels

Igloo hotels are a new variation on the traditional igloo. In several winter destinations, villages of igloos are built for tourists where the guests use sleeping bags that sit on top of reindeer hides in overnight stays. For example, Kakslauttanen Igloo Village, located in the Saariselka fell area in the vicinity of Urho Kekkonen National Park in Finnish Lapland, includes snow igloos for sleeping, an ice gallery, an ice chapel popular for weddings, and a snow restaurant that holds 150 persons. There are also traditional rustic log cabins, and a number of warm glass igloos, which provide a unique opportunity to sleep under the Lapp sky and experience the Aurora Borealis in a comfortable room temperature.[8]

Ice hotels are found in many places in Scandinavia—in Norway, Finland, and Sweden—and are constructed each winter, melting in the spring. The ICEHOTEL in the village of Jukkasjärvi, located next to the town of Kiruna in Sweden is a famous attraction. Originally, the creators started out building a simple igloo, which later turned into the elaborate and now famous "hotel." It is made from the waters of the nearby river Torne, the pure waters of which produce beautiful clear ice used to create ice sculptures and other decorations inside the buildings which are made entirely of snow and ice.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Charles D. Arnold and Elisa J. Hart, "The Mackenzie Inuit Winter House," Arctic 45(2) (June 1992): 199-200. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Richard M. Levy, Peter C. Dawson, and Charles Arnold, "Reconstructing traditional Inuit house forms using three-dimensional interactive computer modeling," Visual Studies 19(1) (2004): 26-35. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Asuilaak Living Dictionary, "Igloo." Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Rich Holihan, Dan Keeley, Daniel Lee, Powen Tu, and Eric Yang, How Warm is an Igloo? Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dan Cruickshank, "What house-builders can learn from igloos," BBC News, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Diamond Jenness, The Indians of Canada (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1977, ISBN 0802063268).

- ↑ Allen O'Bannon and Mike McClelland, Allen & Mike's Really Cool Backcountry Ski Book: Traveling and Camping Skills for a Winter Environment (Chockstone Press, 1996, ISBN 1575400766), 80-86.

- ↑ Kakslauttanen, Igloo Village Kakslautanen.

- ↑ Terri Mapes, "The Ice Hotels in Scandinavia," About.com, Retrieved February 4, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hoyt, Alia. How Igloos Work. HowStuffWorks.com. January 17, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- Jenness, Diamond. The Indians of Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1977. ISBN 0802063268.

- O'Bannon, Allen, and Mike McClelland. Allen & Mike's Really Cool Backcountry Ski Book: Traveling and Camping Skills for a Winter Environment. Chockstone Press, 1996. ISBN 1575400766

- Weiss, Harvey. Shelters, from Teepee to Igloo. Ty Crowell Co, 1988. ISBN 0690045530.

- Yankielun, Norbert E. How to Build an Igloo: And Other Snow Shelters. W. W. Norton, 2007. ISBN 0393732150.

External links

All links retrieved February 24, 2018.

- How Igloos Work at HowStuffWorks

- How to make a Snow Mound Shelter.

- Igloo—the Traditional Arctic Snow Dome.

- My Quinzhee Camping Page.

- How to build an igloo in the Artic pole - 1922 from the 1922 film showing Nanook building an igloo.

- Picture of a Quinzhee.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.