The Japanese tea ceremony (cha-no-yu, chadÅ, or sadÅ) is a traditional ritual in which powdered green tea ("matcha," æ¹è¶) is ceremonially prepared by a skilled practitioner and served to a small group of guests in a tranquil setting. The ritual of the tea ceremony was perfected and popularized by Sen no Rikyu in the sixteenth century. Traditionally the tea ceremony has been deeply related to Zen Buddhism, and contains many aspects that teach a Zen way of life including the attainment of selflessness and a calm state of mind.

Since a tea practitioner is expected to be familiar with the production and types of tea, with kimono, calligraphy, flower arranging, ceramics, incense and a wide range of other disciplines including the cultural history and traditional arts in addition to his or her school's tea practices, the study of tea ceremony takes many years. Even to participate as a guest in a formal tea ceremony requires knowledge of the prescribed gestures and phrases expected of guests, the proper way to take tea and sweets, and general deportment in the tea room.

During a tea ceremony the tea master and participants enjoy delicious tea, appreciate works of art, and share a good time together. In the art of tea the term Ichi-go- Ichi-e (ä¸æä¸ä¼), meaning "one chance in a lifetime," is of extreme importance and signifies that the tea master tries to make the tea with his whole heart. The tea ceremony, Cha-no-yu (è¶ã®æ¹¯, literally "hot water for tea"), usually refers to a single ceremony or ritual, while sadÅ or chadÅ (è¶é, or "the way of tea") refers to the study or doctrine of tea ceremony. The pronunciation sadÅ is preferred by the Omotesenke tradition, while the pronunciation chadÅ is preferred by the Urasenke tradition. Cha-ji (è¶äº) refers to a full tea ceremony with kaiseki (a light meal), usucha (thin tea) and koicha (thick tea), lasting approximately four hours. A chakai (è¶ä¼, literally "tea meeting") does not include a kaiseki meal.

History

Introduction to Japan

The tea ceremony requires years of training and practice... yet the whole of this art, as to its detail, signifies no more than the making and serving of a cup of tea. The supremely important matter is that the act be performed in the most perfect, most polite, most graceful, most charming manner possible. âLafcadio Hearn

Tea was known in Japan as early as the Kamakura era (1185-1338 C.E.). Tea in the form of dancha was introduced to Japan in the ninth century by the Buddhist monk Eichu, who brought the practice from China, where according to legend it had already been known for more than a thousand years. Tea soon became widely popular in Japan, and began to be cultivated locally.

The custom of drinking tea, first for medicinal, and then for purely pleasurable reasons, was already widespread throughout China. In the early ninth century, Chinese author Lu Yu wrote the Ch'a Ching (Cha Jing) (the âClassic of Teaâ), a treatise on tea focusing on its cultivation and preparation. Lu Yu's life had been heavily influenced by Buddhism, particularly the Chan school, which evolved into Zen in Japan, and his ideas would have a strong influence in the development of the Japanese tea ceremony. For Lu Yu, tea symbolized the harmony and mysterious unity of the universe. âHe invested the Cha Jing with the concept that dominated the religious thought of his age, whether Buddhist, Taoist (Daoist), or Confucian: to see in the particular an expression of the universalâ (Shapira, et al., 150).

Lu Yu: The Classic of Tea

Lu Yu's Cha Jing (è¶ç») was the earliest treatise on tea ever written. The Cha Jing is divided into ten chapters. The first chapter expounds the mythological origins of tea in China. It also contains a horticultural description of the tea plant and its proper planting as well as some etymological speculation.

Matcha

In the twelfth century, a new form of tea, matcha (Green powdered tea), was introduced by Eisai, another monk returning from China. He brought seeds that he planted in a friendâs garden, and wrote a book on tea. He presented the book and a sample of the tea to the Shogun, who was ill, and earned a reputation as the father of tea cultivation in Japan. This powdered green tea, which sprouts from the same plant as black tea, is unfermented and ground. A half-century later the monk Dai-o (1236-1308) introduced the ritual of the tea ceremony, which he had observed in Chinese monasteries. Several monks became masters of tea ceremony. Ikkyu (1394-1481), leader of the Daitoku-ji temploe, taught the ritual to one of his disciples, Shuko. Shuko developed the ceremony and adapted it to Japanese taste. The ceremony began to be used in religious rituals in Zen Buddhist monasteries. By the thirteenth century, samurai warriors had begun preparing and drinking matcha in an effort to adopt Zen Buddhism.

Tea ceremony developed as a âtransformative practice,â and began to evolve its own aesthetic, in particular that of wabi. Wabi (meaning quiet or sober refinement, or subdued taste) "is characterized by humility, restraint, simplicity, naturalism, profundity, imperfection, and asymmetry [emphasizing] simple, unadorned objects and architectural space, and [celebrating] the mellow beauty that time and care impart to materialsâ[1] Ikkyu, who revitalized Zen in the fifteenth century, had a profound influence on the tea ceremony.

By the sixteenth century, tea drinking had spread to all levels of Japanese society. Sen no Rikyu (perhaps the most well-known and still revered historical figure of the tea ceremony), followed the concept of his master, Takeno JÅÅ, ichi-go ichi-e, a belief that each meeting should be treasured, for it can never be reproduced. His teachings contributed to many newly developed forms of Japanese architecture and gardens, fine and applied arts, and to the full development of sadÅ. The principles he set forwardâharmony (å wa), respect (æ¬ kei), purity (ç²¾ sei), and tranquility (å¯ jaku)âare still central to tea ceremony today.

Theory of the Tea Ceremony

Origin of Tea Ceremony

Tea was introduced from China by two founders of Zen Buddhist schools, Eisai (end of twelfth century) and Dogen (beginning of the thireenth century). The ceremony of drinking tea gradually became identified with the Zen practice of cultivating the self. During the Muromachi period (fourteenth to sixteenth century), the drinking of tea became prevalent in Japan, and serving tea was used as a form of entertainment. A popular betting game involved identifying the source of different teas. Feudal lords collected luxury tea paraphernalia from China as a hobby, and held large tea ceremonies to display their treasures.

Murata Shuko (1423-1502), a Buddhist monk, condemned gambling or the drinking of sake (rice wine) during the tea ceremony. He praised and valued the simplest and most humble tea-things. He established the foundation for wabi-cha by emphasizing the importance of spiritual communion among the participants of the tea ceremony. Shuko was the first to grasp the tea ceremony as a way of enhancing human life. Takeno Jo-o further developed wabi-cha, and initiated Sen no Rikyu in the new tradition. These tea masters were mostly trained in Zen Buddhism. The tea ceremony embodied the spiritual âsimplificationâ of Zen. Zen teaches one to discard all oneâs possessions, even oneâs own life, in order to return to the original being, which existed before oneâs own father and mother.

Spirit of the Art of Tea

The Wabi tea ceremony is conducted in a tiny, rustic hut to symbolize simplification. The spirit of the art of tea consists of four qualities: harmony (wa), reverence or respect (kei), purity or cleanliness (sei), and tranquility (jaku). Jaku is sabi (rust), but sabi means much more than tranquility.

The atmosphere of the tea house and room creates an ambience of gentleness and harmonious light, sound, touch and fragrance. As you pick up the tea bowl and touch it, you can feel gentleness, charm and peace. The best bowls are thrown by hand, and are mostly irregular and primitively shaped.

The aim of practicing Zen Buddhist meditation is selflessness (the Void). If there is no ego or self, the mind and heart is peace and harmony. The teaching of the tea ceremony promotes this kind of harmony, peace and gentleness.

In the spirit of tea ceremony, respect and homage is a religious feeling. When oneâs feeling of respect moves beyond the self, oneâs eyes can move towards the transcendental Being, God and Buddha. When the feeling of homage is directed back towards oneself, one can discover oneself as unworthy of respect and starts to repent.

Cleanliness is a distinctive feature of the tea ceremony. All the objects in the tea ceremony are neatly arranged in their places according to a certain order. The water used in the tea garden is named âroji.â There is usually the running water or a stone basin for purification. Sen no Rikyu composed this poem:

- "While the roji is meant to be a passageway

- Altogether outside this earthly life,

- How is it that people only contrive

- To besprinkle in with dust of mind?"

Tranquility is the most important of the elements composing the spirit of the tea ceremony. Wabi and Sabi imply tranquility. When Murata Shuko explained the spirit of the tea ceremony, he quoted the following poem composed by a Chinese poet:

âIn the woods over there deeply buried in snow,

Last night a few branches of the plum tree burst out in bloom.â

This Chinese poet showed it to a friend who suggested that it should have been changed from âa few branchesâ to âone branch.â This Chinese poet appreciated his friendâs advice. The image of one branch of a plum tree blooming in woods that are completely covered by deep snow evokes isolation, solitude and Wabi. This is the essence of tranquility.

Ichi-go ichi-e

The tea master lives in a simple hut and when some unexpected visitor comes, he prepares the tea and serves it, and arranges seasonal flowers (chabana) in a simple container. They enjoy quiet and amiable conversation and spend a peaceful afternoon.

Through the performance of a simple the tea ceremony, the participants should learn these things. The seasonal flowers carry a keen sense of the seasons into the tea room, and teach the beauty of nature and that âthe flowerâs life is short.â This means that, as a humanâs life is also short, one must live life as a precious thing.

In the tea ceremony human relationships are important, so the tea master tries to deal with each guest as if it were a unique occasion. Ichi-go ichi-e (ä¸æä¸ä¼, literally "one time, one meeting") is a Japanese term describing a cultural concept often linked with the famed tea master Sen no Rikyu. The term is often translated as "for this time only," "never again," or "one chance in a lifetime," or âtreasure every meeting, for it will never recur.â Ichi-go ichi-e is linked with Zen Buddhism and concepts of transience. The term is particularly associated with the Japanese tea ceremony, and is often brushed onto scrolls that are hung in the tea room. In the context of tea ceremony, ichi-go ichi-e reminds the participants that each tea meeting is unique.

Three Schools of Tea Ceremony

Sansenke

The three best known schools, both in Japan and elsewhere, are associated with sixteenth-century tea master Sen no Rikyu and his descendents via his second wife, and are known collectively as the Sansenke (ä¸å家), or "three houses of Sen." These are the Urasenke, Omotesenke and MushanokÅjisenke. A fourth school, called Sakaisenke (å ºå家), was the original senke founded by Sen no Rikyu. Rikyu's eldest son, Sen no DÅan, took over as head of the school after his father's death, but it soon disappeared because he had no son. Another school, named Edosenke, has no relation to the schools founded by the Sen family.

The Sansenke came about when the three sons of Sen no Rikyu's grandson, tea master Motohaku SÅtan (Rikyu's great-grandsons), each inherited a tea house. KÅshin SÅsa inherited Fushin-an (ä¸å¯©è´) and became the head (iemoto) of the Omotesenke school; SenshÅ SÅshitsu inherited Konnichi-an (ä»æ¥åºµ) and became iemoto of the Urasenke school; and IchiÅ SÅshu inherited KankyÅ«-an (å®ä¼åºµ) and became iemoto of MushanokÅjisenke.

Other Schools

The Sansenke are simply known by their names (for example, Urasenke). Schools that developed as branches or sub-schools of the Sansenkeâor separately from themâare known as "~ryÅ«" (from ryÅ«ha), which may be translated as "school" or "style." New schools often formed when factions split an existing school after several generations.

There are many of these schools, most of them quite small. By far the most active school today, both inside and outside Japan, is the Urasenke; Omotesenke, though popular within Japan, is much less well-represented abroad. MushanokÅjisenke, and most of the other schools, are virtually unknown outside Japan.

Equipment

Tea equipment is called dÅgu (éå ·, literally tools). A wide range of dÅgu is necessary for even the most basic tea ceremony. A full list of all available tea implements and supplies and their various styles and variations could fill a several hundred page book, and thousands of such volumes exist. The following is a brief list of the most essential components:

- Chakin (è¶å·¾), a rectangular, white, linen or hemp cloth used for the ritual cleaning of the tea bowl. Different styles are used for thick and thin tea.

- Fukusa (袱ç´). The fukusa is a square silk cloth used for the ritual cleaning of the tea scoop and the natsume or cha-ire, and for handling hot kettle or pot lids. Fukusa are sometimes used by guests for protecting the tea implements when they are examining them (though usually these fukusa are a special style called kobukusa or "small fukusa." They are thicker, brocaded and patterned, and often more brightly colored than regular fukusa. Kobukusa are kept in the kaishi wallet or in the breast of the kimono). When not in use, the fukusa is tucked into the obi, or belt of the kimono. Fukusa are most often monochromatic and unpatterned, but variations exist. There are different colors for men (usually purple) and women (orange, red), for people of different ages or skill levels, for different ceremonies and for different schools.

- Ladle (hishaku ææ). A long bamboo ladle with a nodule in the approximate center of the handle. Used for transferring water to and from the iron pot and the fresh water container in certain ceremonies. Different styles are used for different ceremonies and in different seasons. A larger style is used for the ritual purification undergone by guests before entering the tea room.

- Tana. Tana, literally "shelves," is a general word that refers to all types of wooden or bamboo furniture used in the preparation of tea; each type of tana has its own name. Tana vary considerably in size, style, features and materials. They are placed in front of the host in the tea room, and various tea implements are placed on or stored in them. They are used in a variety of ways during different tea ceremonies.

- Tea bowl (chawan è¶ç¢). Arguably the most essential implement; without these, tea could not be served or drunk at all. Tea bowls are available in a wide range of sizes and styles, and different styles are used for thick and thin tea (see The tea ceremony, below). Shallow bowls, which allow the tea to cool rapidly, are used in summer; deep bowls are used in winter. Bowls are frequently named by their creators or owners, or by a tea master. Bowls over four hundred years old are said to be in use today, but probably only on unusually special occasions. The best bowls are thrown by hand, and some bowls are extremely valuable. Irregularities and imperfections are prized: they are often featured prominently as the "front" of the bowl.

- Broken tea bowls are painstakingly repaired using a mixture of lacquer and other natural ingredients. Powdered gold is added to disguise the dark color of the lacquer, and additional designs are sometimes created with the mixture. Bowls repaired in this fashion are used mainly in November, when tea practitioners begin using the ro, or hearth, again, as an expression and celebration of the concept of wabi, or humble simplicity.

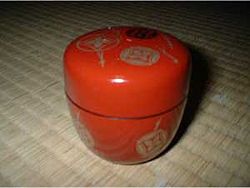

- Tea caddy (natsume, cha-ire æ£ãè¶å ¥ã). Tea caddies come in two basic styles, the natsume and the cha-ire, though there is variation in shape, size and color within the styles. The natsume is named for its resemblance to the natsume fruit (the jujube). It is short with a flat lid and rounded bottom, and is usually made of lacquered or untreated wood. The cha-ire is usually tall and thin (but shapes may vary significantly) and has an ivory lid with a gold leaf underside. Cha-ire are usually ceramic, and are stored in decorative bags. Natsume and cha-ire are used in different ceremonies.

- Tea scoop (chashaku è¶æ). Tea scoops are carved from a single piece of bamboo with a nodule in the approximate center. They are used to scoop tea from the tea caddy into the tea bowl. Larger scoops are used to transfer tea into the tea caddy in the mizuya (æ°´å±) or preparation area. Different styles and colors are used in the Omotesenke and Urasenke tea traditions.

- Whisk (chasen è¶ç ). Tea whisks are carved from a single piece of bamboo. There are thick and thin whisks for thick and thin tea.

- Old and damaged whisks are not simply discarded. Once a year around May, they are taken to local temples and ritually burned in a simple ceremony called chasen kuyÅ, which reflects the reverence with which objects are treated in tea ceremony.

All the tools for tea ceremony are handled with exquisite care. They are scrupulously cleaned before and after each use and before storing. Some components are handled only with gloved hands.

The Tea Ceremony

- When tea is made with water drawn from the depths of mind

- Whose bottom is beyond measure,

- We really have what is called cha-no-yu. âToyotomi Hideyoshi

Two main schools, the Omotesenke (表å家) and Urasenke (è£å家), have evolved, each with its own prescribed rituals. A third school, MushanokÅjisenke, is largely unknown outside Japan. Currently, the Urasenke School is the most active and has the largest following, particularly outside Japan. Within each school there are sub-schools and branches, and in each school there are seasonal and temporal variations in the method of preparing and enjoying the tea, and in the types and forms of utensils and tea used.

All the schools, and most of the variations, however, have facets in common: at its most basic, the tea ceremony involves the preparation and serving of tea to a guest or guests. The following description applies to both Omotesenke and Urasenke, though there may be slight differences depending on the school and type of ceremony.

The host, male or female, wears a kimono, while guests may wear kimono or subdued formal wear. Tea ceremonies may take place outside (in which case some kind of seating will usually be provided for guests) or inside, either in a tea room or a tea house, but tea ceremonies can be performed nearly anywhere. Generally speaking, the longer and more formal the ceremony, and the more important the guests, the more likely the ceremony will be performed indoors, on tatami.

Both tea houses and tea rooms are usually small, a typical floor size being 4 1/2 tatami, which are woven mats of straw, the traditional Japanese floor covering. The smallest tea room can be a mere two mats, and the size of the largest is determined only by the limits of its owner's resources. Building materials and decorations are deliberately simple and rustic.

If the tea is to be served in a separate tea house rather than a tea room, the guests will wait in a garden shelter until summoned by the host. They ritually purify themselves by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths from a small stone basin of water, and proceed through a simple garden along a roji, or "dewy path," to the tea house. Guests remove their shoes and enter the tea house through a small door, and proceed to the tokonoma, or alcove, where they admire the scroll and/or other decorations placed therein and are then seated seiza style on the tatami in order of prestige.

Guests may be served a light, simple meal called a kaiseki (æç³) or chakaiseki (è¶æç³), followed by sake, Japanese rice wine. They will then return to the waiting shelter until summoned again by the host.

If no meal is served, the host will proceed directly to the serving of a small sweet or sweets. Sweets are eaten from special paper called kaishi (æç´); each guest carries his or her own, often in a decorative wallet. Kaishi is tucked into the breast of the kimono.

Each utensilâincluding the tea bowl (chawan), whisk (chasen), and tea scoop (chashaku)âis then ritually cleaned in the presence of the guests in a precise order and using prescribed motions. The utensils are placed in an exact arrangement according to the ritual being performed. When the ritual cleaning and preparation of the utensils is complete, the host will place a measured amount of green tea powder in the bowl and add the appropriate amount of hot water, then whisk the tea using set movements.

Conversation is kept to a minimum throughout. Guests relax and enjoy the atmosphere created by the sounds of the water and fire, the smell of the incense and tea, and the beauty and simplicity of the tea house and its seasonally appropriate decorations.

The bowl is then served to the guest of honor (shokyaku å客, literally the "first guest"), either by the host or an assistant. Bows are exchanged between the host and guest of honor. The guest then bows to the second guest, and raises the bowl in a gesture of respect to the host. The guest rotates the bowl to avoid drinking from its front, takes a sip, murmurs the prescribed phrase, and then takes two or three more sips before wiping the rim, rotating the bowl to its original position, and passing it to the next guest with a bow. The procedure is repeated until all guests have taken tea from the same bowl, and the bowl is returned to the host. In some ceremonies, each guest will drink from an individual bowl, but the order of serving and drinking is the same.

If thick tea, koicha, has been served, the host will then prepare thin tea, or usucha, which is served in the same manner. In some ceremonies, however, only koicha or usucha is served.

After all the guests have taken tea, the host cleans the utensils in preparation for putting them away. The guest of honor will request that the host allow the guests to examine the utensils, and each guest in turn examines and admires each item, including the water scoop, the tea caddy, the tea scoop, the tea whisk, and, most importantly, the tea bowl. The items are treated with extreme care and reverence as they are frequently priceless, irreplaceable, handmade antiques, and guests often use a special brocaded cloth to handle them.

The host then collects the utensils, and the guests leave the tea house. The host bows from the door, and the ceremony is over. A tea ceremony can last between one hour and four to five hours, depending on the type of ceremony performed, and the types of meal and tea served.

Types of ceremony

The ceremonies described below are performed in both the Omotesenke and Urasenke styles.

Chabako demae

Chabako demae (Omotesenke: è¶ç®±ç¹å, Urasenke: è¶ç®±æå) is so called because the equipment is removed from and then replaced into a special box (chabako, literally tea box).

Hakobi demae

Hakobi demae (Omotesenke: éã³ç¹å, Urasenke: éã³æå) is closely related to ryÅ«-rei (see below), but is performed in seiza position. The name comes from the fact that the essential equipmentâbowl, natsume, waste water container, fresh water container, scoops, etc.âare carried (é㶠hakobu) into and out of the tea room.

Obon temae

In Obon Temae (Omotesenke: ãçæå, "tray ceremony"; Urasenke: ç¥çãç¥ç¹å ryaku-bon or ryaku-demaeâryaku: "abbreviated"), the host places a tea bowl, whisk, tea scoop, chakin and natsume on a special tray; these items are covered by the fukusa. Thin tea is prepared on the tray while kneeling seiza-style on the floor. This is usually the first ceremony learned, and is the simplest to perform, requiring neither much specialized equipment nor a lot of time to complete.

Ryū-rei

In RyÅ«-rei (ç«ç¤¼, literally, âstanding bowâ) the tea is prepared at a special table. The guests are seated either at the same table (one guest) or at a separate table. The name refers to the practice of performing the first and last bows standing at the entrance to the tea room. In RyÅ«-rei there is usually an assistant who sits behind the host and moves the host's stool out of the way as needed for standing or sitting. The assistant also serves the tea and sweets to the guests.

Tea ceremony and calligraphy

Calligraphy, mainly in the form of hanging scrolls, plays a central role in the tea ceremony.

Scrolls, often written by famous calligraphers or Buddhist monks or painted by well-known artists, are hung in the tokonoma (scroll alcove) of the tea room. They are selected for their appropriateness for the season, time of day, or theme of the particular ceremony.

Calligraphic scrolls may feature well-known sayings, particularly those associated with Buddhism, poems, descriptions of famous places, or words or phrases associated with tea ceremony. A typical example might have the characters wa kei sei jaku (åæ¬æ¸ å¯, harmony, respect, purity and tranquility). Some contain only a single character, for example, å (wa, "peace," "harmony"), or 風 (kaze, "wind").

Painted scrolls may contain seasonally appropriate images, or images appropriate to the theme of the particular ceremony. Rabbits, for example, might be chosen for a nighttime ceremony because of their association with the moon.

Scrolls are sometimes placed in the machiai (the waiting room) as well.

Tea ceremony and flower arranging

Chabana (è¶è±, literally "tea flowers") is the simple style of flower arranging used in tea ceremony. Chabana has its roots in ikebana, another traditional style of Japanese flower arranging, which itself has roots in Shinto and Buddhism.

Chabana evolved from a less formal style of ikebana, which was used by early tea masters. The chabana style is now the standard style of arrangement for tea ceremony. Chabana is said, depending upon the source, to have been either developed or championed by Sen no Rikyu.

At its most basic, a chabana arrangement is a simple arrangement of seasonal flowers placed in a simple container. Chabana arrangements typically comprise few items, and little or no "filler" material. Unlike ikebana, which often uses shallow and wide dishes, tall and narrow vases are frequently used in chabana. Vases are usually of natural materials such as bamboo, as well as metal or ceramic.

Chabana arrangements are so simple that frequently no more than a single blossom is used; this blossom will invariably lean towards or face the guests.

Kaiseki ryÅri

Kaiseki ryÅri (æç³æç, literally "breast-stone cuisine") is the name for the type of food served during tea ceremonies. The name comes from the practice of Zen monks of placing warmed stones in the breast of the robes to stave off hunger during periods of fasting.

Kaiseki cuisine was once strictly vegetarian, but nowadays fish and occasionally meat will feature.

In kaiseki, only fresh seasonal ingredients are used, prepared in ways that aim to enhance their flavor. Exquisite care is taken in selecting ingredients and types of food, and finished dishes are carefully presented on serving ware that is chosen to enhance the appearance and seasonal theme of the meal. Dishes are beautifully arranged and garnished, often with real leaves and flowers, as well as edible garnishes designed to resemble natural plants and animals. The serving ware and garnishes are as much a part of the kaiseki experience as the food; some might argue that the aesthetic experience of seeing the food is more important than the physical experience of eating it, though of course both aspects are important.

Courses are served in small servings in individual dishes, and the meal is eaten while sitting in seiza. Each diner has a small tray to him- or herself; very important people have their own low table or several small tables.

Kaiseki for tea ceremony is sometimes referred to as chakaiseki (è¶æç³, cha: "tea") meaning "tea kaiseki." Chakaiseki usually includes one or two soups and three different vegetable dishes along with pickles and boiled rice. Sashimi or other fish dishes may occasionally be served, but meat dishes are more rare.

Kaiseki is accompanied by sake.

Tea ceremony and kimono

While kimono used to be mandatory for all participants in a Japanese tea ceremony, this is no longer the case. Still, it is traditional, and on formal occasions most guests will wear kimono. Since the study of kimono is an essential part of learning tea ceremony, most practitioners will own at least one kimono that they will wear when hosting or participating in a tea ceremony. Kimono used to be mandatory dress for students of tea ceremony, and while this practice continues many teachers do not insist upon it; it is not uncommon for students to wear western clothes for practice. This is primarily born of necessity: since most people cannot afford to own more than one or two kimono it is important that they be kept in good condition. Still, most students will practice in kimono at least some of the time. This is essential to learn the prescribed motions properly.

Many of the movements and components of tea ceremony evolved from the wearing of kimono. For example, certain movements are designed with long kimono sleeves in mind; certain motions are intended to move sleeves out of the way or to prevent them from becoming dirtied in the process of making, serving or partaking of tea. Other motions are designed to allow for the straightening of kimono and hakama.

Fukusa (silk cloths) are designed to be folded and tucked into the obi (sash); when no obi is worn, a regular belt must be substituted or the motions cannot be performed properly.

Kaishi (paper) and kobukusa are tucked into the breast of the kimono; fans are tucked into the obi. When western clothes are worn, the wearer must find other places to keep these objects. The sleeves of kimono function as pockets, and used kaishi are folded and placed in them.

For tea ceremony men usually wear a combination of kimono and hakama (a long divided or undivided skirt worn over the kimono), but some men wear only kimono. Wearing hakama is not essential for men, but it makes the outfit more formal. Women wear various styles of kimono depending on the season and the event; women generally do not wear hakama for tea ceremony. Lined kimono are worn by both men and women in the winter months, and unlined ones in the summer. For formal occasions men wear montsuki kimono (plain, single-color kimono with three to five family crests on the sleeves and back), often with striped hakama. Both men and women wear white tabi (divided toe socks).

While men's kimono tend to be plain and largely unpatterned, some women's kimono have patterns on only one side; the wearer must determine which side will be facing the guests and dress accordingly.

Tea ceremony and seiza

Seiza is integral to the Japanese tea ceremony. To sit in seiza (æ£åº§, literally "correct sitting") position, one first kneels on the knees, and then sits back with the buttocks resting on the heels, the back straight and the hands folded in the lap. The tops of the feet lie flat on the floor.

When not seated at tables, both the host and guests sit in seiza style, and seiza is the basic position from which everything begins and ends in a tea ceremony. The host sits seiza to open and close the tea room doors; seiza is the basic position for arranging and cleaning the utensils and preparation of the tea. Even when the host must change positions during parts of the ceremony, these position changes are made in seiza position, and the host returns to sitting seiza when the repositioning is complete. Guests maintain a seiza position during the entire ceremony.

All the bows (there are three basic variations, differing mainly in depth of bow and position of the hands) performed during tea ceremony originate in the seiza position.

Tea ceremony and tatami

Tatami is an integral part of tea ceremony. The main areas of tea rooms and tea houses have tatami floors, and the tokonoma (scroll alcove) in tea rooms often has a tatami floor as well.

Tatami are used in various ways in tea ceremony. Their placement, for example, determines how a person walks through the tea room. When walking on tatami it is customary to shuffle; this forces one to slow down, to maintain erect posture and to walk quietly, and helps one to maintain balance as the combination of tabi and tatami makes for a slippery surface; it is also a function of wearing kimono, which restricts stride length. One must avoid walking on the joins between mats; participants step over such joins when walking in the tea room. The placement of tatami in tea rooms differs slightly from the normal placement. In a four-and-one-half mat room, the mats are placed in a circular pattern around a center mat. It is customary to avoid stepping on this center mat whenever possible as it functions as a kind of table: tea utensils are placed on it for viewing, and prepared bowls of tea are placed on it for serving to the guests. To avoid stepping on it people may walk around it on the other mats, or shuffle on the hands and knees.

Except when walking, when moving about on the tatami one places one's closed fists on the mats and uses them to pull oneself forward or push backwards while maintaining a seiza position.

There are dozens of real and imaginary lines that crisscross any tearoom. These are used to determine the exact placement of utensils and myriad other details; when performed by skilled practitioners, the placement of utensils will vary infinitesimally from ceremony to ceremony. The lines in tatami mats (è¡ gyou) are used as one guide for placement, and the joins serve as a demarcation indicating where people should sit.

Tatami provides a more comfortable surface for sitting seiza-style. At certain times of year (primarily during the new year's festivities) the portions of the tatami where guests sit are covered with a red felt cloth.

Studying tea ceremony

In Japan, those who wish to study tea ceremony typically join what is known in Japanese as a "circle," which is a generic name for a group that meets regularly to participate in a given activity. There are also tea clubs at many junior high schools and high schools, colleges and universities.

Most tea circles are run by a local chapter of an established tea school. Classes may be held at community centers, dedicated tea schools, or at private homes. Tea schools often have widely varied groups that all study in the same school but at different times. For example, there may be a women's group, a group for older or younger students, and so on.

Students normally pay a monthly fee that covers tuition and the use of the school's (or teacher's) bowls and other equipment, the tea itself, and the sweets that students serve and eat at every class. Students must provide their own fukusa, fan, paper, and kobukusa, as well as their own wallet in which to place these items. Students must also provide their own kimono and related accessories. Advanced students may be given permission to wear the school's mark in place of the usual family crests on formal montsuki kimono.

New students typically begin by observing more advanced students as they practice. New students are normally taught mostly by more advanced students; the most advanced students are taught exclusively by the teacher. The first things new students learn are how to correctly open and close sliding doors, how to walk on tatami, how to enter and exit the tea room, how to bow and to whom and when to do so, how to wash, store and care for the various equipment, how to fold the fukusa, how to ritually clean tea bowls, tea caddies and tea scoops, and how to wash and fold chakin. As they master these essential steps, students are also taught how to behave as a guest at tea ceremonies: the correct words to say, how to handle bowls, how to drink tea and eat sweets, how to use paper and sweet picks, and myriad other details.

As they master the basics, students will be instructed on how to prepare the powdered tea for use, how to fill the tea caddy, and finally, how to measure and whisk tea to the proper consistency. Once these basic steps have been mastered, students begin to practice the simplest ceremonies, typically beginning with Obon temae (see above). Only when the first ceremony has been mastered will students move on. Study is through observation and hands on practice; students do not often take notes, and some schools discourage the practice.

Each class ends with the whole group being given brief instruction by the main teacher, usually concerning the contents of the tokonoma (the scroll alcove, which typically features a hanging scroll (usually with calligraphy), a flower arrangement, and occasionally other objects as well) and the sweets that have been served that day. Related topics include incense and kimono, or comments on seasonal variations in equipment or ceremony.

Notes

- â "Introduction: Chanoyu, the Art of Tea" on Urasenke Seattle Homepage.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Okakura, Kakuzo. The Book of Tea. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1977.

- Okakura, Kazuko. The Tea Ceremony: Explore the Ancient Art of Tea. Running Press Book Publishers, 2002.

- Pitelka, Morgan (ed.). Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History, and Practice. London: Routledge Curzon, 2003.

- Sadler, A. Y. Cha-No-Yu: The Japanese Tea Ceremony. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1977.

- Soshitsu, Sen, and V. Dixon Morris (trans.). The Japanese Way of Tea: From Its Origins in China to Sen Rikyu. University of Hawaii Press, 1998.

- Tanaka, S. The Tea Ceremony. New York: Harmony Books, 1977.

- Tanaka, SenâO, Yasushi Inoue, Dendo Tanaka, E. O. Reischauer. The Tea Ceremony (Origami Classroom). Kodansha International, 2000.

See also

External links

All links retrieved December 23, 2024.

- teeweg.de - Practice, history, literature and philosophie of chado (german)

- Urasenke Foundation Seattle Branch (English only)

- Urasenke Konnichian Website (the official homepage of the Urasenke school) (Japanese and English)

- Urasenke La Salle (Philadelphia) (English only)

| ||||

| Black tea | Blended and flavored teas | Chinese tea | Earl Grey tea | Green tea | Herbal tea | Lapsang souchong | Masala chai | Mate tea | Mint tea | Oolong tea | Turkish tea | White tea | Yellow tea | ||||

| Tea culture | Related to tea | |||

| China | India | Japan | Korea | Morocco | Russia | United Kingdom | United States | Samovar | Tea house | Teapot | Tea set | |||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.