Elephant

| Elephant | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

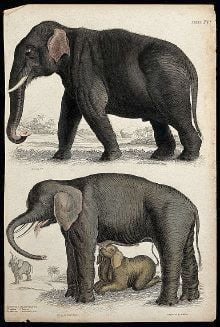

Above, an Indian elephant; below, an African elephant cow suckled by its young. Coloured etching by S. Milne after Captain T. Brown and E. Marechal.

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Elephant is the common name for any of the large land mammals comprising the family Elephantidae in the order Proboscidea, characterized by thick skin, tusks, large pillar-like legs, large flapping ears, and a proboscis, or flexible trunk, that is a fusion of the nose and upper lip. There are only three living species (two in traditional classifications), but many other species are found in the fossil record, appearing in the Pliocene over 1.8 million years ago and having become extinct since the last ice age, which ended about 10,000 years ago. The mammoths are the best known of these.

The three living species of elephants are the African bush elephant or savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana), the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus, also known as the Indian elephant). However, traditionally, and in some present day taxonomies, only one species of African elephant (Loxodonta africana) is recognized, with two subspecies (L. a. africana and L. a. cyclotis), and some taxonomies recognize three species of African elephant.

Elephants are the largest land animals today. Some fossil species, however, were smaller, with the smallest about the size of a large pig.

While advancing their own individual function of survival as a species, elephants also provide a larger function for the ecosystem and for humans. Ecologically, they are key animals in their environment, clearing areas for the growth of young trees, making trails, releasing sources of underground water during the dry season, and so forth. For humans, partially domesticated elephants have been used for labor and warfare for centuries and traditionally were a source of ivory. These massive exotic animals have long been a source of wonder for humans, who feature them prominently in culture and view them in zoos and wildlife parks.

However, the relationship between elephants and humans is a conflicted one, as anthropogenic factors such as hunting and habitat change have been major factors in risks to survival of elephants, the treatment in zoos and circuses has been highly criticized, and elephants have often attacked human beings when their habitats intersect.

Overview

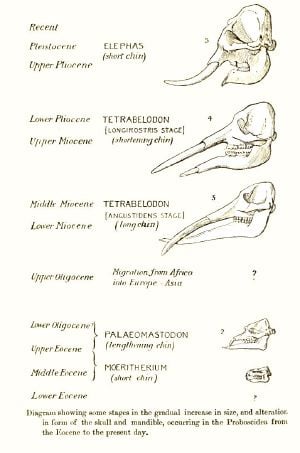

Elephants comprise the family Elephantidae within the order Proboscidea. Proboscidea includes other elephant-like families, notably the Mammutidae, whose members are known as mastodons or mastodonts. Like members of Elephantidae, mastodons have long tusks, large pillar-like legs, and a flexible trunk or probosis. However, mastodons have molar teeth of a different structure. All proboscidians are extinct with the exception of the three extant species within Elephantidae. Altogether, paleontologists have identified about 170 fossil species that are classified as belonging to the Proboscidea, with the oldest dating from the early Paleocene epoch of the Paleogene period over 56 million years ago.

The mammoths, which comprise the genus Mammuthus, are another extinct group that overlapped in time with the mastodons. However, they also belonged to the Elephantidae family, and thus are true elephants. Unlike the generally straight tusks of modern elephants, mammoth tusks typically were curved upward, sometimes strongly curved and spirally twisted, and were long. In northern species, there also was a covering of long hair. As members of Elephantidae, they are close relatives of modern elephants and in particular the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). They lived from the Pliocene epoch, about four million years ago to around 4,500 years ago.

Elephants once were classified along with other thick skinned animals in a now invalid order, Pachydermata. Primelephas, the ancestor of mammoths and modern elephants, appeared in the late Miocene epoch, about seven million years ago.

Among modern-day elephants, those of the genus Loxodonta, known collectively as African elephants, are currently found in 37 countries in Africa. This genus contains two (or, arguably, three, and traditionally one) living species, with the two commonly recognized species L. africana, known as the African bush elephant, and Loxodonta cyclotis, known as the African forest elephant. On the other hand, the Asian elephant species, Elephas maximus, is the only surviving member of its genus, but can be divided into four subspecies.

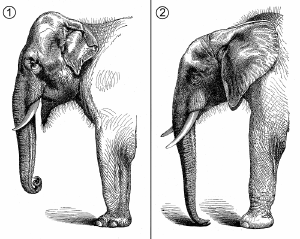

African elephants are distinguished from Asian elephants in several ways, the most noticeable being their ears, which are much larger. The African elephant is typically larger than the Asian elephant and has a concave back. Both African males and females have external tusks and are usually less hairy than their Asian cousins. Typically, only the males of the Asian elephant have large external tusks, while both tusks of African elephants are large. African elephants are the largest land animals (NG).

The elephant's gestation period is 22 months, the longest of any land animal. At birth, it is common for an elephant calf to weigh 120 kilograms (260 pounds). They typically live for 50 to 70 years, but the oldest recorded elephant lived for 82 years (AC).

The largest elephant ever recorded was shot in Angola in 1956. This male weighed about 12,000 kilograms (26,000 pounds) (Sanparks), with a shoulder height of 4.2 meters (14 feet), a meter (yard) taller than the average male African elephant (SDZ 2009). The smallest elephants, about the size of a calf or a large pig, were a prehistoric species that lived on the island of Crete during the Pleistocene epoch (Bate 1907).

The elephant has appeared in cultures across the world. They are a symbol of wisdom in Asian cultures and are famed for their memory and intelligence, where they are thought to be on par with cetaceans (DC 1999), and even placed in the category of the great apes in terms of cognitive abilities for tool use and manufacture (Hart et al. 2001). Aristotle once said the elephant was "the beast which passeth all others in wit and mind" (O'Connell 2007).

Healthy adult elephants have no natural predators (Joubert 2006), although lions may take calves or weak individuals (Loveridge et al. 2006). They are, however, increasingly threatened by human intrusion and poaching. Once numbering in the millions, the African elephant population has dwindled to between 470,000 and 690,000 individuals (WWF 2009). The world population of Asian elephants, also called Indian elephants, is estimated to be around 60,000, about a tenth of the number of African elephants. More precisely, it is estimated that there are between 38,000 and 53,000 wild elephants and between 14,500 and 15,300 domesticated elephants in Asia with perhaps another 1,000 scattered around zoos in the rest of the world (EleAid). The Asian elephants' decline has possibly been more gradual than the African and caused primarily by poaching and habitat destruction by human encroachment.

While the elephant is a protected species worldwide, with restrictions in place on capture, domestic use, and trade in products such as ivory, CITES reopening of "one time" ivory stock sales, has resulted in increased poaching. Certain African nations report a decrease of their elephant populations by as much as two-thirds, and populations in certain protected areas are in danger of being eliminated (Eichenseher 2008). Since poaching has increased by as much as 45%, the actual population is unknown (Gavshon 2008).

The word "elephant" has its origins in the Greek á¼Î»ÎÏαÏ, meaning "ivory" or "elephant" (Soanes and Stevenson 2006). It also has been reported that the word elephant comes via the Latin ele and phant, meaning "huge arch" (AC).

Physical characteristics

Trunk

The proboscis, or trunk, is a fusion of the nose and upper lip, elongated and specialized to become the elephant's most important and versatile appendage. African elephants are equipped with two fingerlike projections at the tip of their trunk, while Asians have only one. According to biologists, the elephant's trunk may have over forty thousand individual muscles in it (Frey), making it sensitive enough to pick up a single blade of grass, yet strong enough to rip the branches off a tree. Some sources indicate that the correct number of muscles in an elephant's trunk is closer to one hundred thousand (MacKenzie 2001)

Most herbivores (plant eaters, like the elephant) possess teeth adapted for cutting and tearing off plant materials. However, except for the very young or infirm, elephants always use their trunks to tear up their food and then place it in their mouth. They will graze on grass or reach up into trees to grasp leaves, fruit, or entire branches. If the desired food item is too high up, the elephant will wrap its trunk around the tree or branch and shake its food loose or sometimes simply knock the tree down altogether.

The trunk is also used for drinking. Elephants suck water up into the trunk (up to fifteen quarts or fourteen liters at a time) and then blow it into their mouth. Elephants also inhale water to spray on their body during bathing. On top of this watery coating, the animal will then spray dirt and mud, which act as a protective sunscreen. When swimming, the trunk makes an excellent snorkel (West 2001; West et al. 2003).

This appendage also plays a key role in many social interactions. Familiar elephants will greet each other by entwining their trunks, much like a handshake. They also use them while play-wrestling, caressing during courtship and mother/child interactions, and for dominance displays: a raised trunk can be a warning or threat, while a lowered trunk can be a sign of submission. Elephants can defend themselves very well by flailing their trunk at unwanted intruders or by grasping and flinging them.

An elephant also relies on its trunk for its highly developed sense of smell. Raising the trunk up in the air and swiveling it from side to side, like a periscope, it can determine the location of friends, enemies, and food sources.

Tusks

The tusks of an elephant are its second upper incisors. Tusks grow continuously; an adult male's tusks will grow about 18Â cm (7Â in) a year. Tusks are used to dig for water, salt, and roots; to debark trees, to eat the bark; to dig into baobab trees to get at the pulp inside; and to move trees and branches when clearing a path. In addition, they are used for marking trees to establish territory and occasionally as weapons.

Both male and female African elephants have large tusks that can reach over 3 meters (10 feet) in length and weigh over 90 kilograms (200Â pounds). In the Asian species, only the males have large tusks. Female Asians have tusks that are very small or absent altogether. Asian males can have tusks as long as the much larger Africans, but they are usually much slimmer and lighter; the heaviest recorded is 39 kilograms (86 pounds).

The tusk of both species is mostly made of calcium phosphate in the form of apatite. As a piece of living tissue, it is relatively soft (compared with other minerals such as rock), and the tusk, also known as ivory, is strongly favored by artists for its carvability. The desire for elephant ivory has been one of the major factors in the reduction of the world's elephant population.

Like humans who are typically right- or left-handed, elephants are usually right- or left-tusked. The dominant tusk, called the master tusk, is generally shorter and more rounded at the tip from wear.

Some extinct relatives of elephants had tusks in their lower jaws in addition to their upper jaws, such as Gomphotherium, or only in their lower jaws, such as Deinotherium. Tusks in the lower jaw are also second incisors. These grew out large in Deinotherium and some mastodons, but in modern elephants they disappear early without erupting.

Teeth

Elephants' teeth are very different from those of most other mammals. Over their lives they usually have 28 teeth. These are:

- The two upper second incisors: these are the tusks

- The milk precursors of the tusks

- 12 premolars, 3 in each side of each jaw (upper and lower)

- 12 molars, 3 in each side of each jaw

This gives elephants a dental formula of:

| 1.0.3.3 |

| 0.0.3.3 |

As noted above, in modern elephants the second incisors in the lower jaw disappear early without erupting, but became tusks in some forms now extinct.

Unlike most mammals, which grow baby teeth and then replace them with a permanent set of adult teeth, elephants have cycles of tooth rotation throughout their entire life. The tusks have milk precursors, which fall out quickly and the adult tusks are in place by one year of age, but the molars are replaced five times in an average elephant's lifetime (IZ 2008). The teeth do not emerge from the jaws vertically like with human teeth. Instead, they move horizontally, like a conveyor belt. New teeth grow in at the back of the mouth, pushing older teeth toward the front, where they wear down with use and the remains fall out.

When an elephant becomes very old, the last set of teeth is worn to stumps, and it must rely on softer foods to chew. Very elderly elephants often spend their last years exclusively in marshy areas where they can feed on soft wet grasses. Eventually, when the last teeth fall out, the elephant will be unable to eat and will die of starvation. Were it not for tooth wear out, the metabolism of elephants likely would allow them to live much longer. However, as more habitat is destroyed, the elephants' living space becomes smaller and smaller; the elderly no longer have the opportunity to roam in search of more appropriate food and will, consequently, die of starvation at an earlier age.

Skin

Elephants are colloquially called pachyderms (from their original scientific classification), which means thick-skinned animals. An elephant's skin is extremely tough around most parts of its body and measures about 2.5 centimeters (1.0 inch) thick. However, the skin around the mouth and inside of the ear is paper-thin.

Normally, the skin of an Asian elephant is covered with more hair than its African counterpart. This is most noticeable in the young. Asian calves are usually covered with a thick coat of brownish red fuzz. As they get older, this hair darkens and becomes more sparse, but it will always remain on their heads and tails.

The various species of elephants are typically grayish in color, but the African elephants very often appear brown or reddish from wallowing in mud holes of colored soil.

Wallowing is an important behavior in elephant society. Not only is it important for socialization, but the mud acts as a sunscreen, protecting their skin from harsh ultraviolet radiation. Although tough, an elephant's skin is very sensitive. Without regular mud baths to protect it from burning, as well as from insect bites and moisture loss, an elephant's skin would suffer serious damage. After bathing, the elephant will usually use its trunk to blow dirt on its body to help dry and bake on its new protective coat. As elephants are limited to smaller and smaller areas, there is less water available, and local herds will often come too close in the search to use these limited resources.

Wallowing also aids the skin in regulating body temperatures. Elephants have difficulty in releasing heat through the skin because, in proportion to their body size, they have very little surface area relative to volume. The ratio of an elephant's mass to the surface area of its skin is many times that of a human. Elephants have even been observed lifting up their legs to expose the soles of their feet, presumably in an effort to expose more skin to the air. Since wild elephants live in very hot climates, they must have other means of getting rid of excess heat.

Legs and feet

An elephant's legs are great straight pillars, as they must be to support its bulk. The elephant needs less muscular power to stand because of its straight legs and large pad-like feet. For this reason, an elephant can stand for very long periods of time without tiring. In fact, African elephants rarely lie down unless they are sick or wounded. Indian elephants, in contrast, lie down frequently.

The feet of an elephant are nearly round. African elephants have three nails on each hind foot, and four on each front foot. Indian elephants have four nails on each hind foot and five on each front foot. Beneath the bones of the foot is a tough, gelatinous material that acts as a cushion or shock absorber. Under the elephant's weight the foot swells, but it gets smaller when the weight is removed. An elephant can sink deep into mud, but can pull its legs out more readily because its feet become smaller when they are lifted.

An elephant is a good swimmer, but it can not trot, jump, nor gallop. It does have two gaits: a walk; and a faster gait that is similar to running.

In walking, the legs act as pendulums, with the hips and shoulders rising and falling while the foot is planted on the ground. With no "aerial phase," the faster gait does not meet all the criteria of running, as elephants always have at least one foot on the ground. However, an elephant moving fast uses its legs much like a running animal, with the hips and shoulders falling and then rising while the feet are on the ground. In this gait, an elephant will have three feet off the ground at one time. As both of the hind feet and both of the front feet are off the ground at the same time, this gait has been likened to the hind legs and the front legs taking turns running (Moore 2007).

Although they start this "run" at only 8 kilomters per hour (Ren and Hutchinson 2007), elephants can reach speeds up to 40 kilometers per hour (25 mph) (Famini and Hutchinson 2003), all the while using the same gait. At this speed, most other four-legged creatures are well into a gallop, even accounting for leg length. Spring-like kinetics could explain the difference between the motion of elephants and other animals (Hutchinson et al. 2003).

Ears

The large flapping ears of an elephant are also very important for temperature regulation. Elephant ears are made of a very thin layer of skin stretched over cartilage and a rich network of blood vessels. On hot days, elephants will flap their ears constantly, creating a slight breeze. This breeze cools the surface blood vessels, and then the cooler blood gets circulated to the rest of the animal's body. The hot blood entering the ears can be cooled as much as ten degrees Fahrenheit before returning to the body.

Differences in the ear sizes of African and Asian elephants can be explained, in part, by their geographical distribution. Africans originated and stayed near the equator, where it is warmer. Therefore, they have bigger ears. Asians live farther north, in slightly cooler climates, and thus have smaller ears.

The ears are also used in certain displays of aggression and during the males' mating period. If an elephant wants to intimidate a predator or rival, it will spread its ears out wide to make itself look more massive and imposing. During the breeding season, males give off an odor from the musth gland located behind their eyes. Poole (1989) has theorized that the males will fan their ears in an effort to help propel this "elephant cologne" great distances.

Behavior, senses, and reproduction

Social behavior

Elephants live in a structured social order. The social lives of male and female elephants are very different. The females spend their entire lives in tightly knit family groups made up of mothers, daughters, sisters, and aunts. These groups are led by the eldest female, or matriarch. Adult males, on the other hand, live mostly solitary lives.

The social circle of the female elephant does not end with the small family unit. In addition to encountering the local males that live on the fringes of one or more groups, the female's life also involves interaction with other families, clans, and subpopulations. Most immediate family groups range from five to fifteen adults, as well as a number of immature males and females. When a group gets too big, a few of the elder daughters will break off and form their own small group. They remain very aware of which local herds are relatives and which are not.

The life of the adult male is very different. As he gets older, he begins to spend more time at the edge of the herd, gradually going off on his own for hours or days at a time. Eventually, days become weeks, and somewhere around the age of fourteen, the mature male, or bull, sets out from his natal group for good. While males do live primarily solitary lives, they will occasionally form loose associations with other males. These groups are called bachelor herds. The males spend much more time than the females fighting for dominance with each other. Only the most dominant males will be permitted to breed with cycling females. The less dominant ones must wait their turn. It is usually the older bulls, forty to fifty years old, that do most of the breeding.

The dominance battles between males can look very fierce, but typically they inflict very little injury. Most of the bouts are in the form of aggressive displays and bluffs. Ordinarily, the smaller, younger, and less confident animal will back off before any real damage can be done. However, during the breeding season, the battles can get extremely aggressive, and the occasional elephant is injured. During this season, known as musth, a bull will fight with almost any other male it encounters, and it will spend most of its time hovering around the female herds, trying to find a receptive mate.

"Rogue elephant" is a term for a lone, violently aggressive wild elephant.

Intelligence

With a mass just over 5 kilograms (11 pounds), elephant brains are larger than those of any other land animal, and although the largest whales have body masses twenty-fold those of a typical elephant, whale brains are barely twice the mass of an elephant's.

A wide variety of behaviors, including those associated with grief, making music, art, altruism, allomothering, play, use of tools, compassion, and self-awareness (BBC 2006) evidence a highly intelligent species on par with cetaceans (DC 1999) and primates (Hart et al. 2001). The largest areas in the elephant brain are those responsible for hearing, smell, and movement coordination. The temporal lobe, responsible for processing of audio information, hearing, and language, is relatively far greater than that of dolphins (which use elaborate echolocation) and humans (who use language and symbols).

Senses

Elephants have well innervated trunks, and an exceptional sense of hearing and smell. The hearing receptors reside not only in ears, but also in trunks that are sensitive to vibrations, and most significantly feet, which have special receptors for low frequency sound and are exceptionally well innervated. Elephants communicate by sound over large distances of several kilometers partly through the ground, which is important for their social lives. Elephants are observed listening by putting trunks on the ground and carefully positioning their feet.

Their eyesight is relatively poor.

Self-awareness

Mirror self recognition is a test of self awareness and cognition used in animal studies. Such tests were performed with elephants. A mirror was provided and visible marks were made on elephants. The elephants investigated these marks, which were visible only via the mirror. The tests also included non-visible marks to rule out the possibility of their using other senses to detect these marks. This shows that elephants recognize the fact that the image in the mirror is their own self and such abilities are considered the basis for empathy, altruism, and higher social interactions. This ability has been demonstrated in humans, apes, dolphins (Plotnik et al. 2006), and magpies (Hirschler 2008).

Communication

In addition to their bellows, roars, and widely recognized trumpet-like calls, elephants communicate over long distances by producing and receiving low-frequency sound (infrasound), a sub-sonic rumbling, which can travel through the ground farther than sound travels through the air. This can be felt by the sensitive skin of an elephant's feet and trunk, which pick up the resonant vibrations much as the flat skin on the head of a drum. This ability is thought also to aid their navigation by use of external sources of infrasound.

To listen attentively, every member of the herd will lift one foreleg from the ground, and face the source of the sound, or often lay its trunk on the ground. The lifting presumably increases the ground contact and sensitivity of the remaining legs.

Discovery of this new aspect of elephant social communication and perception came with breakthroughs in audio technology, which can pick up frequencies outside the range of the human ear. Pioneering research in elephant infrasound communication was done by Katy Payne as detailed in her book, Silent Thunder (Payne 1998). Though this research is still in its infancy, it is helping to solve many mysteries, such as how elephants can find distant potential mates, and how social groups are able to coordinate their movements over extensive range.

Reproduction and life cycle

Elephant social life revolves around breeding and raising of the calves. A female will usually be ready to breed around the age of thirteen, when for the first time she comes into estrus, a short phase of receptiveness lasting a couple of days. Females announce their estrus with smell signals and special calls.

Females prefer bigger, stronger, and, most importantly, older males. Such a reproductive strategy tends to increase their offspring's chances of survival.

After a twenty-two-month pregnancy, the mother will give birth to a calf that will weigh about 113 kilograms (250 pounds) and stand over 76 centimeters (2.5 feet) tall.

Elephants have a very long childhood. They are born with fewer survival instincts than many other animals. Instead, they must rely on their elders to teach them the things they need to know. Today, however, the pressures humans have put on the wild elephant populations, from poaching to habitat destruction, mean that the elderly often die at a younger age, leaving fewer teachers for the young.

A new calf is usually the center of attention for all herd members. All the adults and most of the other young will gather around the newborn, touching and caressing it with their trunks. The baby is born nearly blind and at first relies, almost completely, on its trunk to discover the world around it.

As everyone in the herd is usually related, all members of the tightly knit female group participate in the care and protection of the young. After the initial excitement, the mother will usually select several full-time baby-sitters, or "allomothers," from her group. According to Moss (1988), these allomothers will help in all aspects of raising the calf. They walk with the young as the herd travels, helping the calves along if they fall or get stuck in the mud. The more allomothers a baby has, the more free time its mother has to feed herself. Providing a calf with nutritious milk means the mother has to eat more nutritious food herself. So, the more allomothers, the better the calf's chances of survival. An elephant is considered an allomother during the time she is not able to have her own baby. A benefit of being an allomother is that she can gain experience or receive assistance when caring for her own calf.

Diet and ecology

Diet

Elephants are herbivores, spending 16 hours a day collecting plant food. Their diet is at least fifty percent grasses, supplemented with leaves, bamboo, twigs, bark, roots, and small amounts of fruits, seeds, and flowers. Because elephants only digest about forty percent of what they eat, they have to make up for their digestive system's lack of efficiency in volume. An adult elephant can consume 140 to 270 kilograms (300â600 pounds) of food a day.

Effect on the environment

Elephants are a species upon which many other organisms depend. One particular example of that are termites mounds: Termites eat elephant feces and often begin building their mounds under piles of elephant feces.

Elephants' foraging activities can sometimes greatly affect the areas in which they live. By pulling down trees to eat leaves, breaking branches, and pulling out roots they create clearings in which new young trees and other vegetation can establish itself. During the dry season, elephants use their tusks to dig into dry river beds to reach underground sources of water. These newly dug water holes may then become the only source of water in the area. Elephants make pathways through their environment, which are also used by other animals to access areas normally out of reach. This pathways have sometimes been used by several generations of elephants and today are converted by humans to paved roads.

Species and subspecies

African Elephant

African elephants have traditionally been classified as a single species comprising two distinct subspecies, namely the savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana africana) and the forest elephant (Loxodonta africana cyclotis), but recent DNA analysis suggests that these may actually constitute distinct species (Roca 2001). This split is not universally accepted by experts (AESG 2002) and a third species of African elephant has also been proposed (Eggert et al. 2002).

This reclassification has important implications for conservation, because it means that where previously it was assumed that a single and endangered species comprised two small populations, if in reality these are two separate species, then as a consequence, both could be more gravely endangered than a more numerous and wide-ranging single species might have been. There is also a potential danger in that, if the forest elephant is not explicitly listed as an endangered species, poachers and smugglers might be able to evade the law forbidding trade in endangered animals and their body parts.

The forest elephant and the savanna elephant can also hybridizeâthat is, breed togetherâsuccessfully, though their preferences for different terrains reduce such opportunities. As the African elephant has only recently been recognized to comprise two separate species, groups of captive elephants have not been comprehensively classified and some could well be hybrids.

Under the new two species classification, Loxodonta africana refers specifically to the savanna elephant, the largest of all elephants. In fact, it is the largest land animal in the world, with the males standing 3.2 meters (10 feet) to 4 meters (13 feet) at the shoulder and weighing 3,500 kilograms (7,700 lb) to a reported 12,000 kilograms (26,000 lb) (CITES 1984). The female is smaller, standing about 3 meters (9.8 feet) at the shoulder (Norwood 2002). Most often, savanna elephants are found in open grasslands, marshes, and lakeshores. They range over much of the savanna zone south of the Sahara.

The other putative species, the forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), is usually smaller and rounder, and its tusks thinner and straighter compared with the savanna elephant. The forest elephant can weigh up to 4,500 kilograms (9,900 pounds) and stand about 3 meters (10 feet) tall. Much less is known about these animals than their savanna cousins, because environmental and political obstacles make them difficult to study. Normally, they inhabit the dense African rain forests of central and western Africa, although occasionally they roam the edges of forests, thus overlapping the savanna elephant territories and hybridizing.

Douglas-Hamilton (1979) estimated the continental population of African elephants at around 1.3 million animals. This estimate is controversial and is believed to be a gross overestimate (Parker and Amin 1983), but it is very widely cited and has become a de facto baseline that continues to be used to quantify downward population trends in the species. Through the 1980s, Loxodonta received worldwide attention due to the dwindling numbers of major populations in East Africa, largely as a result of poaching. Today, according to IUCNâs African Elephant Status Report 2007 (Blanc et al. 2007), there are approximately between 470,000 and 690,000 African elephants in the wild. Although this estimate only covers about half of the total elephant range, experts do not believe the true figure to be much higher, as it is unlikely that large populations remain to be discovered (Blanc et al. 2005).

By far the largest populations are now found in Southern and Eastern Africa, which together account for the majority of the continental population. According to a recent analysis by IUCN experts, most major populations in Eastern and Southern Africa are stable or have been steadily increasing since the mid-1990s, at an average rate of 4.5 percent per year (Blanc et al. 2005; Blanc et al. 2007). Elephant populations in West Africa, on the other hand, are generally small and fragmented, and only account for a small proportion of the continental total (Blanc et al. 2003). Much uncertainty remains as to the size of the elephant population in Central Africa, where the prevalence of forest makes population surveys difficult, but poaching for ivory and bushmeat is believed to be intense through much of the region (Blake 2005). The South Africa elephant population more than doubled, rising from 8,000 to over 20,000, in the thirteen years after a 1995 ban on killing the animals (Jacobson 2008). The ban was lifted in February 2008, sparking controversy among environmental groups.

Asian Elephant

A decorated Indian elephant in Jaipur, India.

Several subspecies of Elephas maximus have been identified, using morphometric data and molecular markers. Elephas maximus maximus (Sri Lankan elephant) is found only on the island of Sri Lanka. It is the largest of the Asian elephants. There are an estimated 3,000 to 4,500 members of this subspecies left today in the wild, although no accurate census has been carried out recently. Large males can weigh upward to 5,400 kilograms (12,000 pounds) and stand over 3.4 meters (11 feet) tall. Sri Lankan males have very large cranial bulges, and both sexes have more areas of depigmentation than other Asians. Typically, their ears, face, trunk, and belly have large concentrations of pink-speckled skin.

Elephas maximus indicus (Indian elephant) makes up the bulk of the Asian elephant population. Numbering approximately 36,000, these elephants are lighter gray in color, with depigmentation only on the ears and trunk. Large males will ordinarily weigh only about 5,000 kilograms (11,000 pounds), but are as tall as the Sri Lankan. The mainland Asian can be found in 11 Asian countries, from India to Indonesia. They prefer forested areas and transitional zones, between forests and grasslands, where greater food variety is available.

The Sumatran elephant, Elephas maximus sumatranus, traditionally was recognized as the smallest elephant. Population estimates for this group range from 2,100 to 3,000 individuals. It is very light gray in color and has less depigmentation than the other Asians, with pink spots only on the ears. Mature Sumatrans will usually only measure 1.7 to 2.6 meters (5.6â8.5 feet) at the shoulder and weigh less than 3,000 kilograms (6,600 pounds). It is considerably smaller than its other Asian (and African) cousins and exists only on the island of Sumatra, usually in forested regions and partially wooded habitats.

In 2003, a further subspecies was identified on Borneo. Named the Borneo pygmy elephant, it is smaller and tamer than any other Asian elephants. It also has relatively larger ears, longer tail and straighter tusks.

Evolution

Although the fossil evidence is uncertain, scientists ascertained through gene comparisons that the elephant family seemingly shares distant ancestry with the sirenians (sea cows) and the hyraxes. In the distant past, members of the hyrax family grew to large sizes, and it seems likely that the common ancestor of all three modern families was some kind of amphibious hyracoid. One theory suggests that these animals spent most of their time under water, using their trunks like snorkels for breathing (West 2001; West et al. 2003). Modern elephants have retained this ability and are known to swim in that manner for up to 6 hours and 50 kilometers (30 miles).

In the past, there was a much wider variety of elephant genera, including the mammoths, stegodons, and deinotheria. There was also a much wider variety of species (Todd 2001; Todd 2005).

Threat of extinction

Hunting

Hunting provides a significant risk to the populations of African elephants, both in terms of hunting directly the elephants and in terms of hunting of large predators, allowing competitor herbivores to flourish. A unique threat to the these elephants is presented by hunting for the ivory trade. Adult elephants themselves have few natural predators other thanpeople and, occasionally, lions.

Larger, long-lived, slow-breeding animals, like the elephant, are more susceptible to overhunting than other animals. They cannot hide, and it takes many years for an elephant to grow and reproduce. An elephant needs an average of 140 kilograms (300 pounds) of vegetation a day to survive. As large predators are hunted, the local small grazer populations (the elephant's food competitors) find themselves on the rise. The increased number of herbivores ravage the local trees, shrubs, and grasses.

Men with African elephant tusks, Dar es Salaam, c. 1900

An elephant resting his head on a tree trunk, Samburu National Reserve, Kenya

An elephant in the Ngorongoro crater, Tanzania

Habitat loss

Another threat to elephant's survival in general is the ongoing development of their habitats for agricultural or other purposes. Cultivation of elephant habitat has lead to increasing risk of conflicts of interest with human cohabitants. These conflicts kill 150 elephants and up to 100 people per year in Sri Lanka (SNZP). The Asian elephant's demise can be attributed mostly to loss of its habitat.

As larger patches of forest disappear, the ecosystem is affected in profound ways. The trees are responsible for anchoring soil and absorbing water runoff. Floods and massive erosion are common results of deforestation. Elephants need massive tracts of land because, much like the slash-and-burn farmers, they are used to crashing through the forest, tearing down trees and shrubs for food, and then cycling back later on, when the area has regrown. As forests are reduced to small pockets, elephants become part of the problem, quickly destroying all the vegetation in an area, eliminating all their resources.

National parks

Africa's first official reserve, Kruger National Park, eventually became one of the world's most famous and successful national parks. There are, however, many problems associated with the establishment of these reserves. For example, elephants range through a wide tract of land with little regard for national borders. Once a reserve is established and fence erected, many animals find themselves cut off from their winter feeding grounds or spring breeding areas. Some animals may die as a result, while others, like the elephants, may just trample over the fences, wreaking havoc in nearby fields. When confined to small territories, elephants can inflict an enormous amount of damage to the local landscapes.

Additionally, some reserves, such as Kruger National Park, have, in the opinion of wildlife managers, suffered from elephant overcrowding, at the expense of other species of wildlife within the reserve. On February 25, 2008, with the elephant population having swelled from 8,000 to 20,000 in 14 years, the South Africa announced that they would reintroduce culling for the first time since 1994 to control elephant numbers (Clayton 2008). Nevertheless, as scientists learn more about nature and the environment, it becomes very clear that these parks may be the elephant's last hope against the rapidly changing world around them.

Humanity and elephants

Harvest from the wild

The harvest of elephants, both legal and illegal, has had some unexpected consequences on elephant anatomy beyond that of the risk of extinction. African ivory hunters, by killing only tusked elephants, have given a much larger chance of mating to elephants with small tusks or no tusks at all. The propagation of the absent-tusk gene has resulted in the birth of large numbers of tuskless elephants, now approaching thirty percent in some populations (compared with a rate of about one percent in 1930). Tusklessness, once a very rare genetic abnormality, has become a widespread hereditary trait.

It is possible, if unlikely, that continued artificial selection pressure could bring about a complete absence of tusks in African elephants. The effect of tuskless elephants on the environment, and on the elephants themselves, could be dramatic. Elephants use their tusks to root around in the ground for necessary minerals, reach underground water sources, tear apart vegetation, and spar with one another for mating rights. Without tusks, elephant behavior could change dramatically (LK 1999).

Domestication and use

Elephants have been working animals used in various capacities by humans. Seals found in the Indus Valley suggest that the elephant was first domesticated in ancient India. However, elephants have never been truly domesticated: the male elephant in his periodic condition of musth is dangerous and difficult to control. Therefore elephants used by humans have typically been female, war elephants being an exception: Female elephants in battle will run from a male, thus males are used in war. It is generally more economical to capture wild young elephants and tame them than breeding them in captivity.

The Lao People's Democratic Republic has been domesticating elephants for centuries and still employs an approximate 500 domesticated elephants, the majority of which work in the Xaignabouli province. These elephants are mainly employed in the logging industry, with ecotourism emerging as a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative. Elefantasia is a local INGO aiming to reconvert logging elephants into ecotourism practices, thus allowing Asian elephants the ability to supply their mahouts with income whilst still allowed to breed.

Elephants are also commonly exhibited in zoos and wild animal parks. About 1200 elephants are kept in western zoos. A study shows that the lifespan of elephants in European zoos is about half as long as those living in protected areas in Africa and Asia (Frederick 2008).

Warfare

War elephants were used by armies in the Indian sub-continent, the Warring States of China, and later by the Persian Empire. This use was adopted by Hellenistic armies after Alexander the Great experienced their worth against king Porus, notably in the Ptolemaic and Seleucid diadoch empires. The Carthaginian general Hannibal took elephants across the Alps when he was fighting the Romans, but brought too few elephants to be of much military use, although his horse cavalry was quite successful; he probably used a now-extinct third African (sub)species, the North African (Forest) elephant, smaller than its two southern cousins, and presumably easier to domesticate. A large elephant in full charge could cause tremendous damage to infantry, and cavalry horses would be afraid of them.

Industry

Throughout Myanmar (Burma), Siam, India, and most of South Asia elephants were used in the military for heavy labor, especially for uprooting trees and moving logs, and were also commonly used as executioners to crush the condemned underfoot.

Elephants have also been used as mounts for safari-type hunting, especially Indian shikar (mainly on tigers), and as ceremonial mounts for royal and religious occasions, while Asian elephants have been used for transport and entertainment.

Zoo and circuses

Elephants have traditionally been a major part of circuses around the world, being intelligent enough to be trained in a variety of acts. However, conditions for circus elephants are highly unnatural (confinement in small pens or cages, restraints on their feet, lack of companionship of other elephants, and so on). Perhaps as a result, there are instances of them turning on their keepers or handlers.

There is growing resistance against the capture, confinement, and use of wild elephants (Poole 2007). Animal rights advocates allege that elephants in zoos and circuses "suffer a life of chronic physical ailments, social deprivation, emotional starvation, and premature death" (PETA). Zoos argue that standards for treatment of elephants are extremely high and that minimum requirements for such things as minimum space requirements, enclosure design, nutrition, reproduction, enrichment, and veterinary care are set to ensure the well-being of elephants in captivity.

Elephants raised in captivity sometimes show "rocking behavior," a rhythmic and repetitive swaying which is unreported in free ranging wild elephants. Thought to be symptomatic of stress disorders, and probably made worse by a barren environment (Elzanowski and Sergiel 2006), rocking behavior may be a precursor to aggressive behavior in captive elephants.

Elephant rage

Despite its popularity in zoos, and cuddly portrayal as gentle giants in fiction, elephants are among the world's most potentially dangerous animals. They can crush and kill any other land animal, even the rhinoceros. They can experience unexpected bouts of rage and can be vindictive (Huggler 2006).

In Africa, groups of young teenage elephants attack human villages in what is thought to be revenge for the destruction of their society by massive cullings done in the 1970s and 80s (Siebert 2006; Highfield 2006). In India, male elephants have regularly attacked villages at night, destroying homes and killing people. In the Indian state of Jharkhand, 300 people were killed by elephants between 2000 and 2004, and in Assam, 239 people have been killed by elephants since 2001 (Huggler 2006). In India, elephants kill up to 200 humans every year, and in Sri Lanka around 50 per year.

Among factors in elephant aggression is the fact that adult male elephants naturally periodically enter the state called musth (Hindi for "madness"), sometimes spelled "must" in English.

In popular culture

Elephants are ubiquitous in Western popular culture as emblems of the exotic, because their unique appearance and size sets them apart from other animals and because, like other African animals such as the giraffe, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus, they are not native to areas with Western audiences. Popular culture's stock references to elephants rely on this exotic uniqueness. For instance, a "white elephant" is a byword for something expensive, useless, and bizarre (Van Riper 2002).

As characters, elephants are relegated largely to children's literature, in which they are generally cast as models of exemplary behavior, but account for some of this branch of literature's most iconic characters. Many stories tell of isolated young elephants returning to a close-knit community, such as The Elephantâs Child from Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories (1902), Dumbo (1942), or The Saggy Baggy Elephant (1947). Other elephant heroes given human qualities include Laurent de Brunhoff's anthropomorphic Babar (1935), David McKee's Elmer (1989), and Dr. Seuss's Horton (1940). More than other exotic animals, elephants in fiction are surrogates for humans, with their concern for the community and each other depicted as something to which to aspire (Van Riper 2002).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- African Elephant Specialist Group (AESG). 2002. Statement on the taxonomy of extant Loxodonta. IUCN/SSC. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Animal Corner (AC). n.d. Elephants. Animal Corner. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Bate, D. M. A. 1907. On elephant remains from Crete, with description of Elephas creticus sp.n. Proc. zool. Soc. London August 1, 1907: 238-250.

- BBC. 2006. Elephants' jumbo mirror ability. BBC October 31, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Blake, S. 2005. Central African forests: Final report on population surveys (2003-2005). CITES MIKE Programme. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Blanc, J. J., C. R. Thouless, J. A. Hart, H. T. Dublin, I. Douglas-Hamilton, G. C. Craig, and R. F. W. Barnes. 2003. African Elephant Status Report 2002: An Update From the African Elephant Database. Gland: IUCN. ISBN 2831707072. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Blanc, J. J., R. F. W. Barnes, G. C. Craig, I. Douglas-Hamilton, H. T. Dublin, J. A. Hart, and C. R. Thouless. 2005. Changes in elephant numbers in major savanna populations in eastern and southern Africa. Pachyderm 38: 19-28.

- Blanc, J. J., R. F. W. Barnes, G. C. Craig, H. T. Dublin, C. R. Thouless, I. Douglas-Hamilton, and J. A. Hart. 2007. African Elephant Status Report 2007: An Update From the African Elephant Database. Gland: IUCN. ISBN 9782831709703.

- Clayton, J. 2008. Animal rights outrage over plan to cull South Africa's elephants. Times Online February 26, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- CITES. 1984. CITES Appendix II Loxodonta africana. CITES. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Discovery Communications (DC). 1999. What makes dolphins so smart?. Discovery Communications. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Douglas-Hamilton, I. 1979. The African Elephant Action Plan. IUCN/WWF/NYZS Elephant Survey and Conservation Programme. Final report to US Fish and Wildlife Service. IUCN, Nairobi.

- Eggert, L. S., C. A. Rasner, and D. S. Woodruff. 2002. The evolution and phylogeography of the African elephant inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence and nuclear microsatellite markers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 269(1504): 1993â2006. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Eichenseher, T. 2008. Poaching may erase elephants from Chad Wildlife Park. National Geographic News December 11, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- EleAid. n.d. Asian elephant distribution. EleAid. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Elzanowski, A., and A. Sergiel. 2006. Stereotypic behavior of a female Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus) in a zoo. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 9(3): 223-232. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Famini, D., and J. R. Hutchinson. 2003. Shuffling through the past: The muddled history of the study of elephant locomotion. Royal Veterinary College, University of London. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Frederick, R. 2008. Science Magazine Podcast. Science December 12, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Frei, G. n. D. Anatomy of the elephants. Elephants in Zoo and Circus.

- Gavshon, M. 2008. Poachers leaving elephant orphans. CBS News December 21, 2008.

- Hart, B. L., L. A. Hart, M. McCoy, and C. R. Sarath. 2001. Cognitive behaviour in Asian elephants: Use and modification of branches for fly switching. Animal Behaviour 62(5): 839-847. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Highfield, R. 2006. Elephant rage: They never forgive, either. Sydney Morning Herald February 17, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Hirschler, B. 2008. Mirror test shows magpies are no bird-brains. Reuters August 19, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Huggler, J. 2006. Animal behaviour: Rogue elephants. Independent October 12, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Hutchinson, J. R., D. Famini, R. Lair, and R. Kram. 2003. Biomechanics: Are fast-moving elephants really running? Nature 422: 493â494. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Indianapolis Zoo (IZ). 2008. Elephant anatomy. Indianapolis Zoo. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Jacobson, C. 2008. South Africa to allow elephant killing. National Geographic News February 25, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Joubert D. 2006. Hunting behaviour of lions (Panthera leo) on elephants (Loxodonta africana) in the Chobe National Park, Botswana. African Journal of Ecology 44: 279-281.

- Learning Kingdom (LK). 1999. The Learning Kingdom's cool fact of the day for March 30, 1999: Why are elephants in Africa being born without tusks. Learning Kingdom. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Loveridge, A. J., J. E. Hunt, F. Murindagomo, and D. W. Macdonald. 2006. Influence of drought on predation of elephant (Loxodonta africana) calves by lions (Panthera leo) in an African wooded savannah. Journal of Zoology 270(3): 523â530. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- MacKenzie, P. 2001. The trunk. Elephant Information Repository. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Moore, T. 2007. Biomechanics: A spring in its step. Natural History 116:(4): 28-9.

- Moss, C. 1988. Elephant Memories: Thirteen Years in the Life of an Elephant Family. New York: W. Morrow. ISBN 0688053483.

- National Geographic (NG). n.d. African elephant {Loxodonta africana). National Geographic. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Norwood, L. 2002. Loxodonta africana. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- O'Connell, C. 2007. The Elephant's Secret Sense: The Hidden Lives of the Wild Herds of Africa. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743284410.

- Parker, I., and M. Amin 1983. Ivory Crisis. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 0701126337.

- Payne, K. 1998. Silent Thunder: In the Presence of Elephants. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684801086.

- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). n.d. Elephant-free zoos. SaveWildElephants.com. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Plotnik, J. M., F. B. M. de Waal, and D. Reiss. 2006. Self-recognition in an Asian elephant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(45): 17053â17057. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Poole, J. H. 1989. Announcing intent: The aggressive state of musth in African elephants. Anim. Behav. 37: 140-152.

- Poole, J. 2007. The capture and training of elephants. Amboseli Trust for Elephants. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Ren, L., and J. R. Hutchinson. 2007. The three-dimensional locomotor dynamics of African (Loxodonta africana) and Asian (Elephas maximus) elephants reveal a smooth gait transition at moderate speed. J. Roy. Soc. Interface 5: 195.

- Roca, A. L., N. Georgiadis, J. Pecon-Slattery, and S. J. O'Brien. 2001. Genetic evidence for two species of elephant in Africa. Science 293(5534): 1473. PMID 11520983. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- San Diego Zoo (SDZ). 2009. Animal bytes: Elephant. San Diego Zoo. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Siebert, C. 2006. An elephant crackup? New York Times October 8, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Smithsonian National Zoological Park (SNZP). n.d. Peopleâelephant conflict: Monitoring how elephants use agricultural crops in Sri Lanka. Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Soanes, C., and A. Stevenson. 2006. Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199296340.

- South African National Parks (Sanparks). Frequently asked African elephant questions. South African National Parks. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Todd, N. E. 2001. African Elephas recki: Time, space and taxonomy. In G. Cavarretta, P. Gioia, M. Mussi, and M. R. Palombo, The World of Elephants. Proceedings of the 1st International Congress. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Rome, Italy. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Todd, N. E. 2005. Reanalysis of African Elephas recki: Implications for time, space and taxonomy. Quaternary International 126-128:65-72.

- Van Riper, A. B. 2002. Science in Popular Culture: A Reference Guide. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313318220.

- West, J. B. 2001. Snorkel breathing in the elephant explains the unique anatomy of its pleura. Respiratory Physiology 126(1): 1â8. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- West, J. B., Z. Fu, A. P. Gaeth, and R. V. Short. 2003. Fetal lung development in the elephant reflects the adaptations required for snorkeling in adult life. Respiratory Physiology and Neurobiology 138(2-3): 325â333. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- WWW. 2009. African elephants. World Wide Fund for Nature. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

Further reading

- Debruyne, R., V. Barriel, and P. Tassy. 2003. Mitochondrial cytochrome b of the lyakhov mammoth (proboscidea, mammalia): New data and phylogenetic analyses of elephantidae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 26(3): 421-434.

- Williams, H. 1989. Sacred Elephant. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 0517573202.

| ||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.