Freedom (philosophy)

Freedom is traditionally understood as independence of the arbitrary will of another.[1] Such a state is contrasted with slavery.[2] A slave is constantly subject to the will of another. By contrast a free person can do whatever he chooses as long as he does not break the law and infringe on the freedom of others. This has been described as external freedom or "negative liberty." To the layman, this is understood as: "your freedom ends where my nose begins."

There is also the sense of inner freedom which exists where free will is followed by free action. A person who does not succeed in doing what he sets out to do, because his will fails, is in a sense unfree, a slave to his passions. His will is not free because it is subject to momentary impulses which distract him from accomplishing what he had determined to do. An example would be a person who is an addict. He may want to give up his addiction but cannot and the decisions he makes are shaped by the need to feed the addiction. So freedom comes from self-control. Goethe said, "From the forces that all creatures bind, who overcomes himself his freedom finds."

Complete freedom includes the inner freedom of the will and the external freedom of the environment such that a person's plans and deliberations are not arbitrarily thwarted by either himself or some other agency.

Freedom is not a value but is the ground of values because it allows a person to create and appreciate values, to pursue the classical values of beauty, truth and goodness. It enables people to use their creativity so as to bring joy to God and to others, their family, relatives, friends and wider community. According to the American moral philosopher Susan Wolf, freedom is the ability to act in accordance with the True and the Good. According to people such as Saint Augustine and Confucius, this kind of freedom can reach a point at which it always produces goodness. Thus historically people have struggled not for abstract freedom for its own sake, but for the freedom to be good and do good.

Philosophers have traditionally made a distinction between freedom and license. Freedom is always constrained by laws or rules that apply equally to all members of a society. These laws have a negative quality in that they prohibit certain acts which are damaging to the community or which interfere with another person's freedom. These are traditional laws such as the prohibition of rape, murder and theft etc. If a person violates these laws he ought to be punished. John Locke said that such laws preserve and enlarge freedom.[3] This is why the rule of law is so important to freedom. In contrast license is associated with power and the idea that a person can do anything without censure, an idea first associated with Voltaire. In the modern world many people mistake license for freedom and become angry when they are censured for being selfish, rude, irresponsible and immoral.

Freedom has traditionally been linked with the idea of responsibility. George Bernard Shaw expressed this succinctly, "Liberty means responsibility. That is why most men dread it."[4] A free person has the opportunity and burden of making choices and decisions. This also means that he must bear the consequences of his actions. This theme was explored by Dostoyevsky in the "Legend of the Grand Inquisitor" in The Brothers Karamasov.

Freedom is also said to distinguish human beings from animals who as a result are not treated as moral agents. It is also linked to creativity. Whereas animals make things such as nests their creations lack the free creativity that enables human beings to make original and unique works.

There have been two main attacks on the idea of freedom. One comes from the notion of God's foreknowledge suggesting that an omniscient God already knows what will happen in the future, either because he wills it or just because he knows. This leads on to the notion of predestination. The second has come from the idea of determinism which suggests that in a law governed universe, the law of cause and effect means that the future is already decided. This implies that human freedom is an illusion as all choices and decisions a person makes are determined by physical laws and chemical interactions. A further attack on the idea of human freedom comes from those who argue that human nature is a product of a person's environment and upbringing. All these have the effect of undermining human responsibility and have been used to justify taking away people's freedom.

Historical origins

The ama-gi, a Sumerian cuneiform word, is the earliest known written symbol representing the idea of freedom. The English word "freedom" is an Anglo-Saxon word combining the words "free" and "doom." The word "free" has etymological origins in not having a halter, friend, peace, love, dear and noble. The word "doom" means law and personal judgement or opinion. So a free person does not have a halter round his neck and so is no one's slave or servant and so is a noble person. Such a person follows his own well considered personal judgment which is within the law. Freedom is a sociological concept and without society the word has no meaning. Liberty is often used as an alternative to freedom. It is a Latin word incorporated into English via French.

The most important literature in Europe for the understanding of freedom has been the Bible, especially the Exodus story of the transition of the Hebrews from slavery to a law governed society described in Deuteronomy and Leviticus. Saint Paul expounded a more internal sense of the freedom of the spirit.

The Value of Freedom

Freedom is valuable for the individual and also for society.

For the individual freedom is a pre-requisite for spiritual and moral growth. A person who as they grow older is not given more and more responsibility and the freedom that goes with it does not fully mature. Human beings are treated as moral agents because they are held to be responsible for their actions. If a person is not free then they are not responsible. For example if someone is physically forced to pull a trigger and kill someone they are not treated as a murderer. Freedom enables a person to make decisions that will affect their future. It gives them the chance to take or not to take opportunities that occur instead of having such decisions made by someone else. Thus freedom enables a person to become responsible, following their own lights, pursuing and creating beauty, truth and goodness. The Anglo-Saxon king Alfred the Great (c. 849 – 26 October 899), who was the first known person to have written the word 'freedom' in English, suggested that to be governed by righteousness is to be "on tham hehstan freodome," that is, in the highest freedom. The Christian idea of freedom includes the expectation that a truly free person will live following their conscience. As Saint Augustine said, "Love God and do what you want."

Freedom allows people to pursue their interests within the framework of law. It means that people are not controlled and not part of someone else's plans and purposes. On the contrary as long as they do not break the law, a system of general rules that apply to everyone, they can live where they choose, follow whatever career they wish, buy, sell and trade without restriction, read and write what they like, espouse whatever beliefs and opinions they hold, associate with whomever they wish and form clubs, groups, parties and sects without seeking anyone's permission. In short the freedom to follow their conscience. Such a person would naturally live within the moral law. Of course if a person breaks the law committing murder or stealing they can expect a fair trial followed by an appropriate punishment. The social order that develops in a free society is self-generated. It is not designed or the product of a central plan but is incredibly complex with many different types of relationships. Each person and institution freely makes make their own plans and self-coordinates them with others. It has been called a catallaxy by F.A. Hayek. These relationships are primarily regulated by manners, tradition, custom and in the last resort by laws which describe the limits of acceptable behavior beyond which the state will intervene to punish transgressors. Freedom within the law is thus the basis for a peaceful society as it makes it possible for people with incommensurate religions and opinions to live side by side as neighbors.

The freedom to own property and do with it what one chooses is also important. This has traditionally been expressed through owning land and being able to farm the land and enjoy what one produces. This contrasts with slavery and less so with serfdom where a person doesn't own the land, cannot choose how to farm it and does not directly benefit from his labor. In the modern world this has been transformed into owning a house and creating a garden. There is also the freedom to create, manage and invest in businesses and again to make a profit or loss depending on how hard one works and the decisions one makes. When people have the freedom to be responsible they naturally enough will seek to improve their lot and that of their family and society. Using their creativity to make and create things for others and for mutual sharing and exchange will lead to prosperity for the whole society. This insight formed the basis of Adam Smith's description of and support for the free market.

The epistemological value of freedom rests on the recognition of human ignorance about the past, present and future. Since the future is unknown and unknowable, it is important that people have the opportunity to respond creatively to accidents, opportunities, events and changing circumstances. In free society there is a growth of knowledge as people come up with discuss and perhaps implement new ideas. A society which discourages or tries to control new ideas and innovations will tend to be stagnant and lack the flexibility that is necessary to survive and prosper.[1] This is why Communism was doomed to fail as a planned economy and planned society cannot allow for unplanned innovations and changes and so will fall behind those societies which are free. To establish and maintain a planned society it is necessary punish those who refuse to conform. Furthermore in a society where there is a complete monopoly of employment as under Communism, anyone who loses their job because they upset their employer for whatever reason loses the ability to survive. This freedom to experiment also means the freedom to make mistakes and learn from them. This is why free societies are more moral, just and prosperous.

Two Concepts of Freedom

The British philosopher Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between positive liberty and negative liberty in his essay "Two Concepts of Liberty." He defined negative liberty as the absence of constraints on, or interference with, an agent's possible action. Greater "negative freedom" meant fewer restrictions on possible action. Berlin associated positive liberty with the idea of self-mastery, or the capacity to determine oneself, to be in control of one's destiny. Positive liberty should be exercised within the constraints of negative liberty.

While Berlin granted that both concepts of liberty represent valid human ideals, as a matter of history the positive concept of liberty has proven particularly susceptible to political abuse. He contended that under the influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant and G. W. F. Hegel (all committed to the positive concept of liberty), European political thinkers often equated liberty with forms of political discipline or constraint. Advocates of positive liberty claim that a person who cannot achieve his ambitions because he doesn't have enough resources is not free. Under this understanding poor people are not free because they cannot afford to buy or do the things they want.[5] This is the basis for the idea of freedom from want. To achieve such positive freedom collective political action is necessary to empower such people through a redistribution of wealth. The consequences of such action always lead to the creation of a large state apparatus to restructure human society and the economy. This is usually accompanied by wholesale violence, imprisonment and often murder of people who disagree. So the demand for positive freedom always leads to the loss of negative freedom as people are no longer protected by the law. One example that dominated the twentieth century world was Communism. A more recent example of forcing people to be free is the war in Iraq to create a liberal democracy.

This negative liberty is central to the claim for toleration due to incommensurability. This concept is mirrored in the work of Joseph Raz.

F.A. Hayek made a similar distinction. He described the Anglican tradition of liberty which was developed by John Locke, David Hume, Adam Smith, Edmund Burke and William Paley based on their reflections on living in a free country. He contrasted this with the Gallican tradition of freedom articulated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Condorcet and the Encyclopedists who did not live in a free country and so did not understand freedom. So they mistakenly equated freedom with power. Hayek showed that the opposite to a free society is totalitarianism while the opposite to democracy is authoritarianism. He said that democracy does not guarantee freedom as a majority is always tempted enforce its will upon a minority. J.S. Mill in his book On Liberty described this as the tyranny of the majority. Hayek also pointed out that national independence also is no guarantee of freedom.

Hayek expands this distinction between Anglican and Gallic freedom into a comparison between what he calls true and false individualism. "True individualism affirms the value of the family and all the common efforts of the small community and group … " whereas "false individualism wants to dissolve all these smaller groups into atoms which have no cohesion other than the cohesive rules imposed by the state …"[6] Writing in the 1940s, he observed that whereas Englishmen and Americans he encountered voluntarily conformed to social traditions and conventions, young Germans tried to cultivate an original personality which he thought would make it hard for society based on individualism to function smoothly and would end in dictatorial government to impose order. This continental tradition of false individualism and freedom had influenced philosophers such as J.S. Mill and was being adopted in Britain and America replacing the traditional Anglican view.

Edmund Burke supported the American war of Independence but was the earliest and most perceptive critic of the French Revolution. He predicted that the latter would descend into chaos followed by tyranny because of its mistaken concept of freedom. He emphasized the importance of the inner life to be able to enjoy the fruits of freedom. Otherwise people would descend into self-centeredness, trying to impose their will on others. People without an inner spiritual life find it hard to cope with freedom and often turn to alcohol, drugs and join gangs as an escape. Burke wrote:

- Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites; in proportion as their love of justice is above their rapacity; in proportion as their soundness and sobriety of understanding is above their vanity and presumption; in proportion as they are more disposed to listen to the counsels of the wise and good, in preference to the flattery of knaves. Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.

A Free Society

The concept of political freedom is closely allied with the concepts of civil liberties and individual rights. Most liberal democratic societies are professedly characterized by various freedoms which are afforded the legal protection of the state. Some of these freedoms may include (in alphabetical order):

- Freedom of assembly

- Freedom of association

- Freedom to bear arms

- Freedom of education

- Freedom of movement

- Freedom of the press

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of speech

- Freedom of thought

- Intellectual freedom

- Freedom to trade

To draw examples from the Bill of Rights of the U.S. Constitution, the freedoms or rights in its first ten amendments are negative freedoms in that they prohibit the state from interfering in or curtailing those freedoms. Thus the state (the First Amendment says "Congress," although this has now been expanded to include all governments in the U.S., whether local, state, or national) cannot take away a citizen's freedom of press and publication, religion, assembly, and petition. But the state is not compelled to aid anyone in carrying out any of those freedoms. If you wish to publish your opinion but do not have access to a newspaper column, the state does not need to provide one for you, or if your practice of your religion requires that you have a prayer shawl or a copy of your religion's sacred scripture, the state does not need to provide them for you.

There is at least one positive right, or freedom, that has been given to U.S. citizens by a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court; as a result of the unanimous decision in Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), citizens accused of a crime who cannot afford a lawyer must have one provided for them by the state. In this, not only are U.S. citizens given the freedom to have legal representation if accused (negative freedom) but are provided legal representation by the government (positive freedom) if they are unable to do so themselves.

Some constitutions, especially of European countries, do contain positive rights and freedoms, such as a freedom or right to have a job, housing, medical care, or education. When constitutions do contain such positive rights and freedoms, the state needs to spend money to grant those rights and freedoms, but negative freedom does not require such public or state expenditures.

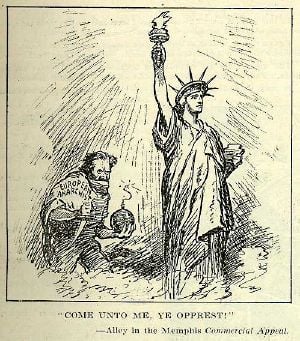

Negative freedom has often been used religiously as a rallying cry for revolution or rebellion. For instance, the Bible records the story of Moses leading his people out of Egypt and its oppression (slavery), and into freedom to worship God. In his famous "I Have a Dream" speech Martin Luther King, Jr. quoted an old spiritual song sung by black American slaves: "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty we are free at last!" The U.N.'s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, however, seems to reflect both negative and positive freedom.

Inner Autonomy

Freedom can also signify inner autonomy, or mastery over one's inner condition. This has several possible significances according to Susan Wolf:[7]

- the ability to act in accordance with the dictates of reason;

- the ability to act in accordance with one's own true self or values;

- the ability to act in accordance with universal values (such as the True and the Good); and

- the ability to act independently of both the dictates of reason and the urges of desires, i.e., arbitrarily (autonomously).

This is to be distinguished from license, which is undisciplined freedom. The former is responsible and expected to issue in a good result for oneself and others, while the latter is irresponsible and selfish, not being able to contribute anything constructive to society. If the social contract contains some universal values, then positive freedom mentioned above may be similar to this responsible type of freedom.

There is an even more internalized type of freedom. In a play by Hans Sachs, for example, the Greek philosopher Diogenes speaks to Alexander the Great, saying: "You are my servants' servant." The philosopher has conquered fear, lust, and anger, whereas Alexander still serves these masters. Although the king has conquered the world without, he has not yet mastered the world within. This kind of mastery is dependent upon no one and nothing other than oneself. Richard Lovelace's poem echoes this experience:

- Stone walls do not a prison make

- Nor iron bars a cage

- Minds innocent and quiet take

- That for an hermitage

Some notable twentieth century individuals who are often held to have exemplified this form of freedom include Nelson Mandela, Rabbi Leo Baeck, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Gandhi, Lech Wałęsa and Václav Havel. Attaining this kind of inner peace has often been associated also with religions such as Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. It may involve a considerable effort of self-control to reach this.

One important issue is: Does inner freedom always issue in a good result? The answer unfortunately is in the negative in reality. However, people such as Saint Augustine said that the type of freedom which is attained by saints beyond this world always results in good things because it is the libertas (liberty) in the sense of being non posse peccare (not able to sin). According to him, it is different from the posse no peccare (ability not to sin) which Adam and Eve possessed even before their fall. This is equivalent to what Confucius claimed to have accomplished at the age of seventy: "At seventy, I could follow what my heart desired, without transgressing what was right" (Lunyu II.4.20).

Freedom and Determinism

Determinists argue that in a law governed universe the future is contained within the past. Everything that will happen tomorrow could be predicted by a being that knows all facts about the past and the present and knows all natural laws that govern the universe. In other words things cannot be other than they are. So if everything including the behavior of human beings is determined by the immutable laws of cause and effect, free will and hence freedom is an illusion. People do not really make free choices as what they decide to do has already been determined by the laws of physics and chemical interactions.

Other variants of this include genetic determinism, the idea that a person's character and behavior is determined by their genes; environmental determinism, the idea that a person's behavior and character is determined by their social environment and upbringing.

Quantum mechanics and chaos theory have undermined scientific determinism.

The religious version of determinism is predestination the idea that an omniscient God who transcends time and space knows what will happen in the future. This could be because everything that happens is part of God's will or plan. It is hard to reconcile freedom with the idea of predestination.

God is regarded as free because as an uncaused being all his actions originate within himself. Living beings cannot be simply explained in terms of the laws of physics and chemistry. The motivations of healthy human beings are explained in terms of reasons and not causes. When we try to explain a person in terms of causes we demote a person to a thing.[8] So freedom is often described as a mystery.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 F.A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (University of Chicago Press, 2011, ISBN 9780226315393).

- ↑ Ernest Barker, Reflections on Government (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1942).

- ↑ John Locke, Second Treatise on Government.

- ↑ George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman: Maxims for Revolutionaries (London, 1903).

- ↑ G.A. Cohen, History, Labour, and Freedom (Oxford: Clarendon, 1988, ISBN 0198248164).

- ↑ F.A. Hayek, "Individualism: True and False," in Individualism and Economic Order. (Chicago, 1948, ISBN 0226320936), 23.

- ↑ Susan Wolf, Freedom Within Reason (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- ↑ Roger Scruton, Modern Philosophy: An Introduction (Penguin Books, 1996, ISBN 0140249079).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics Lesley Brown (ed.), David Ross (trans.). Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0199213615

- Augustine (Saint). On Free Choice of the Will, Translated, with introd. and notes, by Thomas Williams. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co., 1993. ISBN 0872201880

- Barker, Ernest. Reflections on Government. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press, 1942.

- Berlin, Isaiah. Two Concepts of Liberty. London: Clarendon Press, 1958

- Cohen, G.A. History, Labour, and Freedom. Oxford: Clarendon, 1988. ISBN 0198248164

- Hayek, F.A. Individualism and Economic Order. University of Chicago Press, 1996 (original 1948). ISBN 0226320936

- Hayek, F.A. The Constitution of Liberty. University of Chicago Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0226315393

- Hobbes, Thomas. Of Liberty and Necessity. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521596688

- Hume, David. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Edited with an introduction and notes by Peter Millican. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0199211582

- MacCallum, G.C., Jr. "Negative and Positive freedom." Philosophical Review 76 (1967): 312-334.

- Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty. Ware [England]: Wordsworth Editions, 1996 (original 1859). ISBN 1853264644

- Plato. The Republic, Translated by G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co., 1974. ISBN 0915144034

- Schiller, Friedrich. Letters upon the Aesthetic Education of Man. reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 141913003X

- Scruton, Roger. Modern Philosophy: An Introduction. Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 0140249079

- Shaw, George Bernard. Man and Superman: Maxims for Revolutionaries. London, 1903.

- Wolf, Susan. Freedom Within Reason. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0195056167

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- Philosophy of Freedom website.

- Sovereignty and Freedom.

- Free Will Catholic Encyclopedia.

- American Revolution's Legacy: Freedom.

- The goddess Liberty (Liberté)

- Various entries on Freedom Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings | Eastern philosophy · Western philosophy | History of philosophy (ancient • medieval • modern • contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Information · History · Human nature · Language · Law · Literature · Mathematics · Mind · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Science · Social science · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Language · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ethics |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.