Kingdom of Dahomey

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

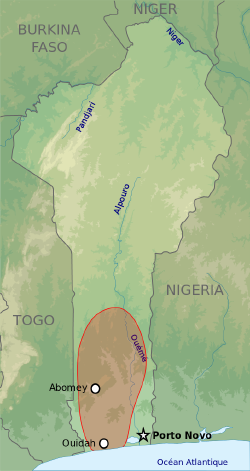

Dahomey, a precolonial West African kingdom, is located in what is now southern Benin. Founded in the seventeenth century, Dahomey reached the height of its power and prestige during the heyday of the Atlantic slave trade in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the late nineteenth century, it was conquered by French troops from Senegal and incorporated into France's West African colonies. Dahomey was the last of the traditional African kingdoms to succumb to European colonization.

Unusual in Africa, Dahomey was ruled by a form of absolute monarchy. The king was surrounded by an assemblage of royalty, commoners, and slaves in a rigidly stratified society. Dahomey utilized women in key areas: each male official in the field had a female counterpart at court who monitored his activities and advised the king. Female soldiers, called Amazons by the Europeans, served as royal bodyguards when not in combat.

In the movement of African decolonization following World War II, Dahomey became an autonomous republic, gaining full independence in 1960. The Republic of Dahomey changed its name to Benin in 1975.

History

The origins of Dahomey can be traced back to the Fon people of the interior of the African continent, who banded together in a conglomerate in order to oppose the political authority of the Yoruba People of Oyo. Technically an official subject of the Yoruba of Oyo, the Fon people were forced to pay tribute to their political conquerors and were subjected to cavalry raids made by the Oyo armies in order to supply the slave trade.

In order to unite the Fon people in opposition to the Yoruba, leaders who rose to positions of power capitalized on the ability to perform well on the battlefield. With military skill being prized as the ultimate expression of authority, the king of the Fon came to embody uncontested authority, and his will was enforced by the army.

King Wegbaja rose to power in roughly 1650 and came to embody the militaristic values that had become embedded among the Fon people. Based in his capital of Abomey, Wegbaja and his successors succeeded in establishing a highly centralized state with a deep-rooted tradition of autocratic centralized government. Economically, Wegbaja and his successors profited mainly from the slave trade and relations with slavers along the Atlantic coast. As he embarked on wars to expand their territory, they began using rifles and other firearms traded with French and Spanish slave-traders for young men captured in battle, who fetched a very high price from the European slave-merchants.

Later expansion of Dahomey towards the coast met with resistance from the alafin, or ruler, of Oyo, who resented the political and economic rise of their subject. Soon after the march to the sea, the alafin of Oyo sent cavalry raids to Oyo in 1726, completely defeating the army. Later cavalry invasions in 1728, 1729, and 1730, in which Oyo proved sucessful, hindered the plans for coastal expansion.

In 1902 Dahomey was declared a French colony. In the movement of African decolonization following World War II, Dahomey became an autonomous republic, gaining full independence in 1960. The Republic of Dahomey changed its name to Benin in 1975.

Dahomey has been featured in a variety of literary and popular works. In 1971, American novelist Frank Yerby published The Man From Dahomey, a historial novel set partially in Dahomey, which introduces rich Dahomean culture to the reader. In Dahomey was the first all-black musical performed on Broadway.

Kings of Dahomey

Gangnihessou, unknown - 1620

According to tradition, Gangnihessou came from a dynasty that originated in the sixteenth century. Based in Tado, a city on the banks of the Moro River (in modern day Togo), the dynasty rose to eminence on the basis of one of his four brothers, who became the king of Great Ardra. After the death of the king, his territories were divided among the three remaining brothers, one of which was Gangnihessou.

Gangnihessou came to rule around 1620 but was soon dethroned by his brother, Dakodonou, while traveling through the kingdom. His symbols were the male Gangnihessou-bird (a rebus for his name), a drum, a hunting stick and a throwing stick.

Dakodonou, 1620-1645

Dakodonou was the second King of Dahomey, who ruled from 1620 to 1645. Dakodonou is portrayed as a brutal and violent man. His symbols were an indigo jar (a reference to his murder of a certain indigo planter named Donou, whose body he made sport of by rolling it around in his indigo jar, and whose name he appended to his own original name, 'Dako'), a tinder box, and a war club. Before dying, Dakodonou named his nephew, Aho Houegbadja, as his successor.

Houegbadja (or Webaja) 1645-1685

The third King of Dahomey was Aho Houegbadja, who succeeded his uncle, Dakodonou. He ruled from the time of his uncle's death in 1645 until 1685.

Houegbadja established the political authority and boundaries of Abomey proper by naming the city as his capital. By building his palace (named "Agbome," meaning "in the midst of the ramparts") near Guedevi, an area located a few kilometers to the northwest of Bohicon, he established the area as the seat of political authority. He was responsible for forming the political culture that would continue to characterize Dahomey, with a reign that was marked by autocratic rule. Houegbadja's symbols were a fish (houe), fish trap (adja), and war club hoe (kpota).

Akaba, 1685-1708

Houegbadja's successor was his son, Houessou Akabawas, who became the fourth King of Dahomey. He ruled from 1685 to 1708.

Houessou Akaba's reign was characterized by war and military expansion. His enemies, the Nago (Western Yoruba) kings, attacked Abomey and burned the town. But the warriors of Abomey ultimately defeated the Nago armies and the kingdom extended to include the banks of the Oueme River. Akaba failed, however, to capture Porto-Novo. Akaba's symbols were the warthog and a saber.

Akaba died of smallpox in 1708. Because his only son, Agbo Sassa, was only ten years old, Akaba was succeeded instead by his brother, Dossou Agadja.

Agadja, 1708-1732

Ruling from 1708 to 1740, Dossou Agadja was the fifth King of Dahomey. Despite the fact that Agadja had gained the throne due to the youth of Agbo Sassa, the rightful heir, he refused to surrender power when the boy came of age and forced Agbo Sassa into exile.

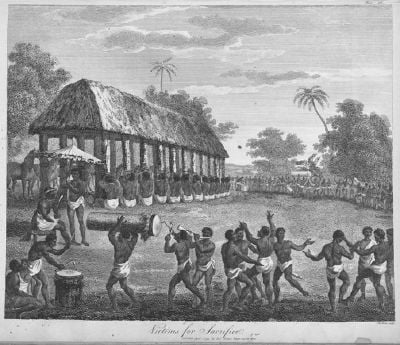

Agadja's reign was characterized by continual warfare. The Yoruba soldiers of the kingdom of Oyo defeated the army of Abomey. The peace terms required Agadja to pay tribute to the Oyo Empire, a system that continued for the next hundred years. The Tribute of the Kingdom of Abomey to the King of Oyo took the form of an annual tribute in young men and women destined for slavery or death in ceremonies, as well as cloth, guns, animals and pearls.

The kingdom of Abomey grew during Agadja's reign, and conquered Allada in 1724. In 1727 it conquered the kingdom of Savi, and gained control of its major city, Ouidah. When Abomey conquered Savi and Ouidah, it gained direct access to the trading ports along the southern coast and took over the lucrative slave trade with the Europeans. As a result, Agadja's symbol is a European caravel boat. Agadja's victory over Ouidah came, in part, as a result of his use of a corps of women shock-troopers, called Dahomey Amazons by the Europeans after the women warriors of Greek myth, in his army. The Amazons became a dynastic tradition.

Agadja was succeeded by Tegbessou.

Tegbessou, 1732-1774

Tegbessou was the sixth King of Dahomey, ruling from 1740 to 1774. His reign was characterized by internal corruption and failed foreign policy. He killed many coup-plotters and political enemies, refused to pay tribute to the Yoruba, and lost many battles in the punitive raids that followed.

His main symbol is a buffalo wearing a tunic. His other symbols are the blunderbuss, a weapon he gave his warriors (his reign marked the first time the Dahomey Royal Army had ready access to firearms) and a door decorated with three noseless heads, a reference to his victory over a rebellious tributary people, the Benin Zou, whose corpses he mutilated.

During Tegbessou's reign, the Dahomey enlarged the slave trade, waging a bitter war on their neighbors. It is said 10,000 people were captured and sold into slavery, including another important slave trader, the King of Whydah. King Tegbessou made £250,000 a year selling people into slavery in 1750.[1]

Tegbessou was succeeded by Kpengla.

Kpengla, 1774-1789

The seventh king of Dahomey, Kpengla, ruled from 1774 to 1789. His reign focused on expansion, and dramatically increased the size of the kingdom. In order to expand westward, he killed the chief of the Popo people, Agbamou, and spread his empire into modern day Togo. He destroyed the villages of Ekpe and Badagry (in what is now Nigeria), that were interfering with Dahomey's regional monopoly on the slave trade.

His main symbol is the akpan bird, a trade gun (flintlock), and an Amazon warrior striking her head against a tree. Kpengla was succeeded by Agonglo.

Agonglo, 1789-1797

Kpengla was succeeded by his son, Agonglo. The eighth King of Dahomey, he ruled from 1789 to 1797.

Agonglo instituted several reforms which pleased his subjects: taxes were lowered, and a greater distribution of gifts was made during the annual customs. He reformed the shape of the asen, or sacrificial altar, and supported the surface by ribs rather than a metal cone, typical of the earlier Allada style altars.

After the period of aggressive military expansion of his father, Agonglo consolidated the rule of the dynasty, his few military battles, however, were sucessful. His symbol is the pineapple.

Agonglo is notable in being the first of the Dahomean kings to marry a European woman. One of his wives was Sophie, a Dutch woman of mixed ancestry. Agonglo was succeeded by his eldest son, Adandozan.

Adandozan, 1797-1818

Technically the ninth King of Dahomey, Adandozan is not counted as one of the 12 kings. His name has largely been erased from the history of Abomey and to this day is generally not spoken out loud in the city. He became king when, in 1797, the previous king died, leaving the throne to his eldest son.

Adandozan's symbols were a baboon with a swollen stomach, full mouth, and ear of corn in hand (an unflattering reference to his enemy, the King of Oyo), and a large parasol ('the king overshadows his enemies'). These symbols are not included in Abomey appliques, for the same reasons that Adandozan is not included in Abomey's history.

The traditional stories of Adandozan's rule portray him as extremely cruel: he is said to have raised hyenas to which he would throw live subjects for amusement. He has been portrayed as hopelessly mad, struggling foolishly with the European powers.

The commonly told story is that he refused to pay Francisco Felix da Souza, a Brazilian merchant and trader who had become a major middle-man in the Ouidah slave market. Instead, he imprisoned and tortured de Souza, and then attempted to have his own ministers sell the slaves directly. According to legend, de Souza escaped with the aid of Gakpe, Adandozan's brother, who returned from exile for that purpose. In return, de Souza helped Gakpe marshall a military force and take the throne with the assistance of the terrified council of ministers. Gakpe then put Adandozan in prison.

This traditional portrayal may be wrong: like Richard II of England in the Wars of the Roses, Adandozan may have been the object of a propagandistic rewriting of history after he lost the throne, turned into a monster by his successor as a means of excusing the coup d'état and legitimizing the new regime. All stories agree that Adandozan tried to force more favorable terms of trade with the Europeans involved in the export of slaves, and seriously undermined the power of the extended royal family and Vodun cult practitioners at court through administrative reforms.

It may be that these policies themselves provoked Adandozan's powerful opponents to support a coup against him. In order to justify the coup, Gakpe may then have been obliged to have oral historians tell of the monstrous and mad Adandozan.

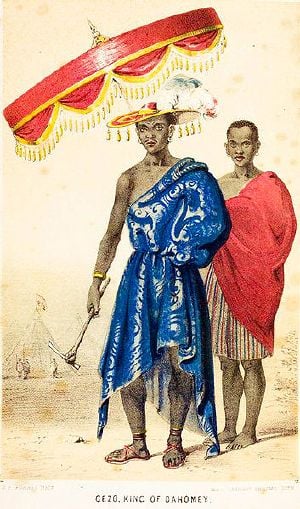

Ghezo (Gakpe) 1818-1856

Ghezo was the ninth King of Dahomey and is considered one of the greatest of the 12 historical kings. He ruled from 1818 to 1858. His name before ascending to the throne was Gakpe.

Ghezo's symbols are two birds on a tree, a buffalo, and a clay jar sieve with holes in it held by two hands, a symbol of unity. Ghezo is said to have used the sieve as a metaphor for the kind of unity needed for the country to defeat its enemies and overcome its problems; it takes everyone's hand to block the sieve's holes and hold water. The pierced clay jar upheld by multiple hands has become a national symbol in Benin, a large portrayal of it is the backdrop of the speaker's podium in Benin's National Assembly.

Ghezo ascended to the throne after he overthrew his brother, Adandozan, in a coup d'état. The traditional stories state that Adandozan was a cruel ruler, but it is possible these stories may have been invented by Ghezo's historians to justify the coup.

Throughout his reign, Ghezo waged a military campaign every year during the dry season. His prisoners-of-war were sold into slavery, thus fattening the royal treasury, increasing the annual budget, and making war a very efficient means of raising revenue. Due to the increased strength of his army and capital, Ghezo put an end to the Oyo tribute paying. He formalized his army, gave his 4,000 Dahomey Amazon female warriors uniforms, required soldiers to drill with guns and sabres regularly, and was able to repulse Oyo's attack when it came.

From the time of King Ghezo onward, Dahomey became increasingly militaristic, with Ghezo placing great importance on the army, its budget and its structures. An intrinsic part of the army of Dahomey, which increased in importance as the state became more militaristic, was the elite fighting force known as the Amazons.

Ghezo was also seen as an extremely shrewd administrator. Because of his slave revenues, he could afford to lower taxes, thus stimulating the agricultural and mercantile economy: agriculture expanded, as did trade in a variety of goods with France. He instituted new judicial procedures, and was considered to be a just judge of his subjects. He was much loved, and his sudden death in a battle against the Yoruba was considered a tragedy.

However loved by his own people, Ghezo's legacy includes his making a major contribution to the slave trade. He said in the 1840s that he would do anything the British wanted him to do apart from giving up slave trade: "The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth…the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery…" [1]

Ghezo was succeeded by Glele.

Glele, 1856-1889

Badohou, who took the throne name Glele, is considered (if Adandozan is not counted) to be the tenth King of Dahomey. He succeeded his father, Ghezo, and ruled from 1858 to 1889.

Glele continued his father's successful war campaigns, in part to avenge his father's death, in part to capture slaves. Glele also signed treaties with the French, who had previously acquired a concession in Porto-Novo from its king. The French were successful in negotiating with Glele and receiving a grant for a customs and commerce concession in Cotonou during his reign. Glele resisted English diplomatic overtures, however, distrusting their manners and noting that they were much more activist in their opposition to the slave trade: though France itself had outlawed slavery at the end of the 1700s, it allowed the trade to continue elsewhere; Britain outlawed slavery in the U.K. and in its overseas possessions in 1833, and had its navy make raids against slavers along the West African coast beginning in 1840.

Glele, despite the formal end of the slave trade and its interdiction by the Europeans and New World powers, continued slavery as a domestic institution: his fields were primarily cared for by slaves, and slaves became a major source of 'messengers to the ancestors', in other words, sacrificial victims in ceremonies.

Near the end of Glele's reign, relations with France deteriorated due to Cotonou's growing commercial influence and differences of interpretation between Dahomey and France regarding the extent and terms of the Cotonou concession grant. Glele, already on his death bed, had his son Prince Kondo take charge of negotiations with the French.

Glele's symbols are the lion and the ritual knife of the adepts of Gu; of fire, iron, war, and cutting edges.

Glele died on December 29, 1889, to be succeeded by Kondo, who took the name Behanzin.

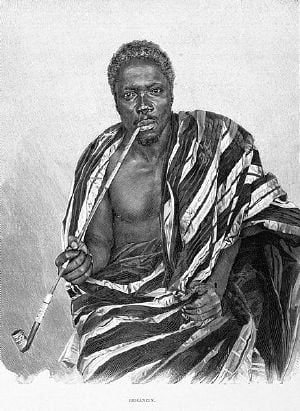

Behanzin, 1889-1894

Behanzin, though the twelfth, is considered the eleventh (if Adandozan is not counted) King of Dahomey. Upon taking the throne, he changed his name from Kondo to Behanzin, as it was traditional for Dahomey kings to assume a throne name. He succeeded his father, Glele, and ruled from 1889 to 1894. Behanzin was Abomey's last independent ruler established through traditional power structures, and was considered to be a great ruler.

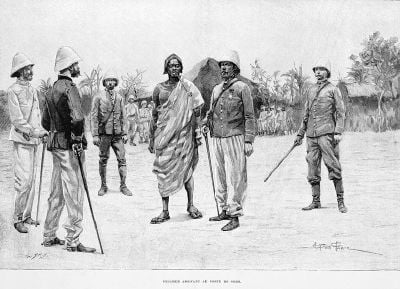

Behanzin was seen by his people as intelligent and courageous. He saw that the Europeans were gradually encroaching on his kingdom, and as a result attempted a foreign policy of isolating the Europeans and rebuffing them. Just before Glele's death, Behanzin declined to meet French envoy Jean Bayol, claiming conflicts in his schedule due to ritual and ceremonial obligations. As a result, Bayol returned to Cotonou to prepare to go to war against Behanzin, named king upon Glele's death. Seeing the preparations, the Dahomeans attacked Bayol's forces outside Cotonou in 1890; the French army stood fast due to superior weaponry and a strategically advantageous position. Eventually Behanzin's forces were forced to withdraw. Behanzin returned to Abomey, and Bayol to France for a time.

Peace lasted two years, during which time the French continued to occupy Cotonou. Both sides continued to buy arms in preparation for another battle. In 1892, the soldiers of Abomey attacked villages near Grand Popo and Porto-Novo in an effort to reassert the older boundaries of Dahomey. This was seen as an act of war by the French, who claimed interests in both areas. Bayol, by now named Colonial Governor by the French, declared war on Behanzin. The French justified the action by characterizing the Dahomeans as savages in need of civilizing. Evidence of this savagery, they stated, was the practice of human sacrifice during the annual customs celebrations and at the time of a king's death, and the continued practice of slavery.

The French were victorious in attaining the surrender of Behanzin in 1894, though they did not procur his signature of national surrender or treaty. He lived out the remainder of his life in exile in Martinique and Algeria. After his death, his remains were returned to Abomey.

His symbols are the shark, the egg, and a captive hanging from a flagpole (a reference to a boastful and rebellious Nago practitioner of harmful magic from Ketou whom the king hanged from a flagpole as punishment for his pride). But, his most famous symbol is the smoking pipe.

Behanzin was succeeded by Agoli-agbo, his distant relative and one-time Army Chief of Staff, the only potential ruler which the French were willing to instate.

Agoli-agbo

Agoli-agbo is considered to have been the twelfth, and last, King of Dahomey. He took the throne after the previous king, Behanzin, went into exile after a failed war with France. He was in power from 1894 to 1900.

The exile of Behanzin did not legalize the French colonization. The French general Alfred Dodds offered the throne to every one of the immediate royal family, in return for a signature on a treaty establishing a French protectorate over the Kingdom; all refused. Finally, Behanzin's Army Chief of Staff (and distant relative), Prince Agoli-agbo was appointed to the throne, as a 'traditional chief' rather than head of state of a sovereign nation, by the French when he agreed to sign the instrument of surrender. He 'reigned' for only six years, assisted by a French Viceroy. The French prepared for direct administration, which they achieved on February 12, 1900. Agoli-agbo went into exile in Gabon, and the Save River. He returned to live in Abomey as a private citizen in 1918.

Agoli-agbo's symbols are a leg kicking a rock, an archer's bow (a symbol of the return to traditional weapons under the new rules established by the colonial administrators), and a broom.

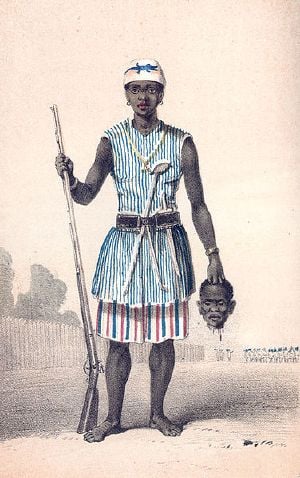

Dahomey Amazons

The Dahomey Amazons were an all-female military regiment of Fon people in the Kingdom of Dahomey. They were so named by Western observers and historians due to their similarity to the legendary Amazons described by the Ancient Greeks.

King Houegbadja, the third king, is said to have originally began the group which would become the Amazons as a corps of royal bodyguards after building a new palace at Abomey. Houegbadja's son King Agadja developed these bodyguards into a militia and successfully used them in Dahomey's defeat of the neighboring kingdom of Savi in 1727. European merchants recorded their presence, as well as similar female warriors amongst the Ashanti. For the next hundred years or so, they gained a reputation as fearless warriors. Though they fought rarely, they usually acquitted themselves well in battle.

From the time of King Ghezo, Dahomey became increasingly militaristic. Ghezo placed great importance on the army and increased its budget and formalized its structures. The Amazons were rigorously trained, given uniforms, and equipped with Danish guns obtained via the slave trade. By this time the Amazons consisted of between 4,000 and 6,000 women, about a third of the entire Dahomey army.

European encroachment into West Africa gained pace during the latter half of the nineteenth century, and in 1890 the Dahomey King Behanzin began fighting French forces (mainly made up of Yoruba, who the Dahomeans had been fighting for centuries). It is said that many of the French soldiers fighting in Dahomey hesitated before shooting or bayoneting the Amazons. The resulting delay led to many of the French casualties. Ultimately, bolstered by the French Foreign Legion, and armed with superior weaponry including machine guns, the French inflicted casualties that were ten times worse on the Dahomey side. After several battles, the French prevailed. The Legionnaires later wrote about the "incredible courage and audacity" of the Amazons.

The last surviving Amazon died in 1979.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 The Story of Africa: Slavery BBC. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alpern, Stanley B. Amazons of Black Sparta : The Women Warriors of Dahomey . New York: New York University Press, 1998. ISBN 0814706770

- Atkin, Tony, and Joseph Rykwert. Structure and Meaning in Human Settlements. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2005. ISBN 1931707839

- Carter, Gwendolen Margaret. Five African States; responses to diversity: the Congo, Dahomey, the Cameroun Federal Republic, the Rhodesias and Nyasaland [and] South Africa. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1963. ASIN B0006D75TK

- Cook, Will Marion. In Dahomey: A Negro Musical Comedy. Andesite Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1375787291

- Davidson, Basil. West Africa before the colonial era: a history to 1850. London: Longman, 1998. ISBN 0582318521

- Decalo, Samuel. Historical Dictionary of Dahomey (People's Republic of Benin). Scarecrow Press, 1976. ASIN B000TWMR3W

- Ellis, A.B. The Ewe-speaking peoples of the Slave Coast of West Africa, their religion, manners, customs, laws, languages, &c. Andesite Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1297514500

- Grossman, Dave. On killing: the psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995. ISBN 0316330000

- Holmes, Richard. Acts of war: the behavior of men in battle. New York: Free Press of Glencoe,1985. ISBN 0029150205

- Newark, Tim, and Angus McBride. Women warlords: an illustrated military history of female warriors. London: Blandford, 1990. ISBN 0713719656

- Peukert, Werner. 1978. Der atlantische Sklavenhandel von Dahomey: (1740-1797): Wirtschaftsanthropologie u. Sozialgeschichte. Wiesbaden: Steiner. ISBN 3515024042

- Ronen, Dov. 1975. Dahomey: between tradition and modernity. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801409276

External Links

All links retrieved September 20, 2022.

- Kingdom of Dahomey. World History at KMLA.

- The History of the Kingdom of Dahomey Black History Month

- The Women Soldiers of Dahomey UNESCO: Women in History.

- Wonders: Dahomey Kingdom The Slave Kingdoms, PBS.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Dahomey  history

- Gangnihessou  history

- Dakodonou  history

- Houegbadja  history

- Akaba  history

- Agadja  history

- Tegbessou  history

- Kpengla  history

- Agonglo  history

- Adandozan  history

- Ghezo  history

- Glele  history

- Behanzin  history

- Dahomey_Amazons  history

- Agoli-agbo  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.