Occupation of Japan

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At the end of the Second World War, a ravaged Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, led by the United States with contributions also from Australia, British India, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. This foreign presence marked the first time since the unification of Japan that the island nation had been occupied by a foreign power. The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation, and subsequent to its coming into force on April 28, 1952, Japan was once again an independent state.

The U.S. ended its occupation in part to bolster its efforts in the Korean War, as well as out of a larger overall concern over the rise of communism around the globe. The occupation was unprecedented in terms of the magnanimity of the victor over the vanquished nation, as the U.S. concentrated on rebuilding the nation and fostering democratic institutions without a policy of vindictiveness. Much of the credit for this policy goes to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the American military governor in Japan from 1945-1951, who was given unprecedented authority by Washington to use his best judgment in the occupation. The character of present-day Japan is due in large part to the foundation laid by the American occupation.

Surrender

On August 6, 1945 an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, followed by a second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9.[1] The attacks reduced these cities to rubble and killed and maimed vast numbers of civilians. Partly in response to devastation caused by the new weapon, as well as fear of the Soviet entry into the Pacific war which occurred on August 8, Japan initially surrendered to the Allies on August 14, 1945, when Emperor Hirohito accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration.[2] On the following day, Hirohito formally announced Japan's surrender on the radio.

The announcement was the emperor's first ever radio broadcast and the first time most citizens of Japan ever heard their sovereign's voice.[3] This date is known as Victory Over Japan, or V-J Day, and marked the end of World War II and the beginning of a long road to recovery for a shattered Japan.

On V-J Day, United States President Harry Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP), to supervise the occupation of Japan.[4] Due to his physical appearance, MacArthur, an American war hero, was dubbed "blue-eyed shogun" and "Japan's Savior" during his tenure in the occupied nation.[5] During the war, the Allied Powers had considered dividing Japan among themselves for the purposes of occupation, as was done for the occupation of Germany. Under the final plan, however, SCAP was given direct control over the main islands of Japan (Honshū, Hokkaidō, Shikoku and Kyūshū) and the immediately surrounding islands,[6] while outlying possessions were divided between the Allied Powers as follows:

- Soviet Union: Korea north of the 38th parallel, Sakhalin, and most of the Kuril Islands; after receiving the surrender of Japanese troops in Manchuria, sovereignty was to be restored to China

- United States: Korea south of the 38th parallel, Okinawa, the Amami Islands, the Ogasawara Islands and Japanese possessions in Micronesia

- Republic of China: Taiwan (originally sovereign Chinese territory) and the Pescadores

The Soviet Union insisted on occupying the northernmost island of Hokkaidō.[7] However, President Truman adamantly refused Joseph Stalin's request, seeing a precedent of communization of territory it occupied in the Soviet zone in Eastern Europe; ultimately Truman successfully resisted any significant Soviet role in Japan. However, in August 1945, U.S. military leaders believed it was not possible to keep the Soviets out of northern Korea, whose troops had already entered Korea early that month, due to the distance of the nearest available U.S. forces at the time of Japan's surrender.[8]

The Far Eastern Commission and Allied Council For Japan was also established to supervise the occupation of Japan.[9] Japanese officials left for Manila on August 19 to meet MacArthur and to be briefed on his plans for the occupation. On August 28, 150 U.S. personnel flew to Atsugi, Kanagawa Prefecture. They were followed by the USS Missouri, whose accompanying vessels landed the 4th Marine Division on the southern coast of Kanagawa. Other Allied personnel followed.

MacArthur arrived in Tokyo on August 30,[10] and immediately decreed several laws: No Allied personnel were to assault Japanese people. No Allied personnel were to eat the scarce Japanese food. Flying the Hinomaru or "Rising Sun" flag was initially severely restricted (although individuals and prefectural offices could apply for permission to fly it). The restriction was partially lifted in 1948 and completely lifted the following year. The Hinomaru was the de facto albeit not de jure flag throughout World war II and the occupation period.[11] During the early years of the occupation, its use was temporarily restricted to various degrees. Sources differ on the use of the terms "banned" and "restricted." John Dower discusses the use of "banned": " …the rising sun flag and the national anthem, both banned by GHQ..[12] " … Even ostensible Communists found themselves waving illegal rising-sun flags."[13] Steven Weisman goes on to note that "… the flag… [was] banned by Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur, Supreme Commander and administrator of Japan after the war."[14] Other sources offer a more detailed and nuanced explication, as for example Christopher Hood: "After the war, SCAP (Supreme Command Allied Powers) had stopped the use of Hinomaru… However, in 1948, it was decided that Hinomaru could be used on national holidays, and all other restrictions were lifted the following year."[15] Further information is given by D. Cripps: "… [before 1948] by notifying the occupation forces in an area, individuals could apply to raise the flag and, depending on the national holiday and region, the prefectural office could be given permission to raise the flag."[16] Moreover, Goodman and Refsing use the phrase "restricted, though not totally banned" and further note that flying the flag was considered anathema by many Japanese themselves in the postwar decades, and its use has been a subject of national debate.[17] See Flag of Japan for more information.

On September 2, Japan formally surrendered with the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri.[18] Allied (primarily American) forces were set up to supervise the country.[19] MacArthur was technically supposed to defer to an advisory council set up by the Allied powers but in practice did everything himself. His first priority was to set up a food distribution network; following the collapse of the Japanese government and the wholesale destruction of most major cities virtually everyone was starving. Even with these measures, millions were still on the brink of starvation for several years after the surrender.[20][21]

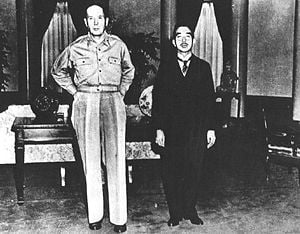

Once the food network was in place, at a cost of up to US$1 million per day, MacArthur set out to win the support of Emperor Hirohito. The two men met for the first time on September 27; the photograph of the two together is one of the most famous in Japanese history. However, many were shocked that MacArthur wore his standard duty uniform with no tie instead of his dress uniform when meeting the emperor. MacArthur may have done this on purpose, to send a message as to what he considered the emperor's status to be.[22] With the sanction of Japan's reigning monarch, MacArthur had what he needed to begin the real work of the occupation. While other Allied political and military leaders pushed for Hirohito to be tried as a war criminal, MacArthur resisted such calls and rejected the claims of members of the imperial family such as Prince Mikasa and Prince Higashikuni and intellectuals like Tatsuji Miyoshi who asked for the emperor's abdication,[23] arguing that any such prosecution would be overwhelmingly unpopular with the Japanese people.[24]

By the end of 1945, more than 350,000 U.S. personnel were stationed throughout Japan. By the beginning of 1946, replacement troops began to arrive in the country in large numbers and were assigned to MacArthur's Eighth Army, headquartered in Tokyo's Dai-Ichi building (formerly belonging to a life insurance firm). Of the main Japanese islands, Kyūshū was occupied by the 24th Infantry Division, with some responsibility for Shikoku. Honshū was occupied by the First Cavalry Division. Hokkaidō was occupied by the 11th Airborne Division.

By June 1950, all of these army units had suffered extensive troop reductions, and their combat effectiveness was seriously weakened. When North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, elements of the 24th Division were flown into South Korea to try to stem the massive invasion force there, but the green occupation troops, while acquitting themselves well when suddenly thrown into combat almost overnight, suffered heavy casualties and were forced into retreat until other Japan occupation troops could be sent to assist.

The official British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), composed of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand personnel, was deployed in Japan on February 21, 1946. While U.S. forces were responsible for overall military government, BCOF was responsible for supervising demilitarization and the disposal of Japan's war industries.[25] BCOF was also responsible for occupation of several western prefectures and had its headquarters at Kure. At its peak, the force numbered about 40,000 personnel. During 1947, BCOF began to decrease its activities in Japan, and it was officially wound up in 1951.[26]

Accomplishments of the Occupation

Disarmament

Japan's postwar constitution, adopted under Allied supervision, included a "Peace Clause" (Article 9), which renounced war and banned Japan from maintaining any armed forces.[27] This was intended to prevent the country from ever becoming an aggressive military power again. However, within a decade, America was pressuring Japan to rebuild its army as a bulwark against Communism in Asia after the Chinese Revolution and the Korean War, and Japan established its Self-Defense Forces.[28] Traditionally, Japan's military spending has been restricted to about 1% of its GNP, though this is by popular practice, not law, and has fluctuated up and down from this figure.[28] Recently, past Prime Ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Shinzo Abe, and other politicians have tried to repeal or amend the clause. Although the American Occupation was to demilitarize the Japanese, due to an Asian threat of communism, the Japanese military slowly regained powerful status. Japan currently has the fourth largest army based on dollars spent on army resources. There is significant concern in Asia that Japan's defense spending will continue to grow and that it could repeal Article 9.

Industrial disarmament

In order to further remove Japan as a potential future threat to the U.S., the Far Eastern Commission decided that Japan was to be partly de-industrialized. The necessary dismantling of Japanese industry was foreseen to have been achieved when Japanese standards of living had been reduced to those existing in Japan in the period 1930-34 (see Great Depression).[29][30] In the end the adopted program of de-industrialization in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the similar U.S. "industrial disarmament" program in Germany (see Industrial plans for Germany).[29]

Liberalization

The Allies attempted to dismantle the Japanese Zaibatsu or industrial conglomerates. However, the Japanese resisted these attempts, claiming that the zaibatsu were required in order for Japan to compete internationally, and therefore somewhat looser industrial groupings known as keiretsu evolved.[31] A major land reform was also conducted, led by Wolf Ladejinsky of General Douglas MacArthur's SCAP staff. However, Ladejinsky has stated that the real architect of reform was Socialist Hiro Wada, former Japanese Minister of Agriculture.[32] Between 1947 and 1949, approximately 5.8 million acres (23,470 km², or approximately 38 percent of Japan's cultivated land) of land were purchased from landlords under the government's reform program, and resold at extremely low prices (after inflation) to the farmers who worked them.[33] By 1950, three million peasants had acquired land, dismantling a power structure that the landlords had long dominated.[34]

Democratization

In 1946, the Diet ratified a new Constitution of Japan which followed closely a model copy prepared by the Occupation authorities, and was promulgated as an amendment to the old Prussian-style Meiji Constitution. The new constitution guaranteed basic freedoms and civil liberties, gave women the right to vote, abolished nobility, and, perhaps most importantly, made the emperor the symbol of Japan, removing him from politics.[35] Shinto was abolished as a state religion, and Christianity reappeared in the open for the first time in decades. On April 10, 1946, an election that saw 79 percent voter turnout among men and 67 percent among women[36] gave Japan its first modern prime minister, Shigeru Yoshida.

Unionization

This turned out to be one of the greatest hurdles of the occupation, as communism had become increasingly popular among the poorer Japanese workers for several decades, and took advantage of Japan's recent left-leaning atmosphere. In February 1947, Japan's workers were ready to call a general strike, in an attempt to take over their factories; MacArthur warned that he would not allow such a strike to take place, and the unions eventually relented, making them lose face and effectively subduing them for the remainder of the occupation.

Education reform

Before and during the war, Japanese education was based on the German system, with "Gymnasium" (English: High Schools) and universities to train students after primary school. During the occupation, Japan's secondary education system was changed to incorporate three-year junior high schools and senior high schools similar to those in the U.S.: junior high became compulsory but senior high remained optional.[37] The Imperial Rescript on Education was repealed, and the Imperial University system reorganized. The longstanding issue of restricting Kanji usage, which had been planned for decades but continuously opposed by more conservative elements, was also resolved during this time. The Japanese written system was drastically reorganized to give the Tōyō kanji, predecessor of today's Jōyō kanji, and orthography was greatly altered to reflect spoken usage.

Purging of war criminals

While these other reforms were taking place, various military tribunals, most notably the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Ichigaya, were trying Japan's war criminals and sentencing many to death and imprisonment. However, many suspects such as Tsuji Masanobu, Nobusuke Kishi, Yoshio Kodama and Ryoichi Sasakawa were never judged,[38] while the Showa Emperor,[39] all members of the imperial family implicated in the war such as Prince Chichibu, Prince Asaka, Prince Hiroyasu Fushimi, Prince Higashikuni and Prince Takeda, and all members of Unit 731 (a unit responsible for atrocious acts of biological and chemical warfare)[40] were exonerated from criminal prosecutions by MacArthur.

Before the war crimes trials actually convened, the SCAP, the IPS and Shōwa officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the imperial family from being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the Emperor. High officials in court circles and the Shōwa government collaborated with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while the individuals arrested as Class A suspects and incarcerated in Sugamo prison solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility.[41] Thus, "months before the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for Pearl Harbor to former prime minister Hideki Tōjō"[42] by allowing "the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the Emperor would be spared from indictment."[42] And "with the full support of MacArthur's headquarters, the prosecution functioned, in effect, as a defense team for the emperor."[43]

For historian John W. Dower,

"Even Japanese peace activists who endorse the ideals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo charters, and who have labored to document and publicize Japanese atrocities, cannot defend the American decision to exonerate the emperor of war responsibility and then, in the chill of Cold War, release and soon afterwards openly embrace accused right-wing war criminals like the later prime minister Kishi Nobusuke."[44]

In retrospect, apart from the military officer corps, the purge of alleged militarists and ultranationalists that was conducted under the Occupation had relatively small impact on the long-term composition of men of influence in the public and private sectors. The purge initially brought new blood into the political parties, but this was offset by the return of huge numbers of formally purged conservative politicians to national as well as local politics in the early 1950s. In the bureaucracy, the purge was negligible from the outset…. In the economic sector, the purge similarly was only mildly disruptive, affecting less than sixteen hundred individuals spread among some four hundred companies. Everywhere one looks, the corridors of power in postwar Japan are crowded with men whose talents had already been recognized during the war years, and who found the same talents highly prized in the "new" Japan."[45]

Politics

Political parties had begun to revive almost immediately after the occupation began. Left-wing organizations, such as the Japan Socialist Party and the Japan Communist Party, quickly reestablished themselves, as did various conservative parties. The old Seiyukai and Rikken Minseito came back as, respectively, the Liberal Party (Nihon Jiyuto) and the Japan Progressive Party (Nihon Shimpoto). The first postwar elections were held in 1946 (women were given the franchise for the first time), and the Liberal Party's vice president, Yoshida Shigeru (1878-1967), became prime minister. For the 1947 elections, anti-Yoshida forces left the Liberal Party and joined forces with the Progressive Party to establish the new Democratic Party of Japan (Minshuto). This divisiveness in conservative ranks gave a plurality to the Japan Socialist Party, which was allowed to form a cabinet, which lasted less than a year. Thereafter, the socialist party steadily declined in its electoral successes. After a short period of Democratic Party administration, Yoshida returned in late 1948 and continued to serve as prime minister until 1954. However, because of a heart failure Yoshida was replaced in 1955.

End of the Occupation

In 1949, MacArthur rubber-stamped a sweeping change in the SCAP power structure that greatly increased the power of Japan's native rulers, and as his attention (and that of the White House) diverted to the Korean War by mid-1950, the occupation began to draw to a close. The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation, and when it went into effect on April 28, 1952[46], Japan was once again an independent state (with the exceptions of Okinawa,[47] which remained under U.S. control until 1972, and Iwo Jima, which remained under U.S. control until 1968). Even though some 47,000 U.S. military personnel remain in Japan today, they are there at the invitation of the Japanese government under the terms of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan and are not as an occupying force.

Cultural Reaction

Hirohito’s surrender broadcast (marking the first time the emperor spoke directly to his people)[6] was a profound shock to Japanese citizens. After years of being told about Japan’s military might and the inevitability of victory, these beliefs were proven false in just a few minutes.[48] But for many people, these were only secondary concerns since they were also facing starvation and homelessness.

Post-war Japan was chaotic. The air raids on urban centers left millions displaced and food shortages, created by bad harvests and the demands of the war, worsened when the importation of food from Korea, Taiwan, and China ceased.[49] The atomic bombs utilized in Hiroshima and Nagasaki had decimated these cities. Repatriation of Japanese living in other parts of Asia only aggravated the problems in Japan as these displaced people put more strain on already scarce resources. Over 5.1 million Japanese returned to Japan in the 15 months following October 1, 1945.[50] Alcohol and drug abuse became major problems. Deep exhaustion, declining morale and despair was so widespread that it was termed the "kyodatsu condition."[51] Inflation was rampant and many people turned to the black market in order to buy even the most basic goods. Prostitution also increased considerably. Prostitutes, known as panpan, were considered cultural misfits by their fellow citizens, and by the end of the occupation approximately 90 percent of them had contracted venereal diseases.[52]

In the 1950s, kasutori culture emerged. In response to the scarcity of the previous years, this sub-culture, named after the preferred drink of the artists and writers who embodied it, emphasized escapism, entertainment and decadence.[53] A renewed interest in the culture of Occupied Japan can be found in the Gordon W. Prange Collection at the University of Maryland.[54] On returning to the United States, he brought back hundreds of thousands of items including magazines, speeches, children's literature, and advertisements, which were all subject to censorship, which now provides a unique resource now archived and made available to historians and researchers. Prange was the author of At Dawn We Slept, which gave the history of the Japanese invasion from the Japanese perspective.

The phrase "shikata ga nai," or "nothing can be done about it," was commonly used in both the Japanese and American press to encapsulate the Japanese public's resignation to the harsh conditions endured while under occupation. However, not everyone reacted the same way to the hardships of the postwar period. While some succumbed to the difficulties, many more were resilient. As the country regained its footing, they were able to bounce back as well.

See also

- Far Eastern Commission

- Japanese war crimes

- World War II

- Task Force 31

- Military rule

- 1945 in Japan

- History of Japan

- Pacific War

Notes

- ↑ Takemae Eiji. 2002. Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy. (New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 0826462472), 42.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 46.

- ↑ Andrew Gordon. 2003. A Modern History of Japan. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195110609), 226.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 4.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Eiji, 2002, 47.

- ↑ Tsuyoshi Hasegawa. 2005. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674016939), 271ff.

- ↑ Hasegawa, 2005, 271ff.

- ↑ Glossary: Birth of the Constitution of Japan. National Diet Library. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 3.

- ↑ Roger Goodman, and Kirsten Refsing. 1992. Ideology and Practice in Modern Japan. (London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0415061024), 33. "The [Hinomaru] was indispensable for seeing new recruits off to war. On the day the recruit was to leave… neighbors gathered in front of his house, where the Japanese flag was displayed… all shouted banzai for the send-off, waving smaller flags."

- ↑ Dower, John W. 1999. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. (New York, NY: Norton. ISBN 0393046869), 226.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 336.

- ↑ Steven Weisman. April 29, 1990. For Japanese, Flag and Anthem Sometimes Divide. [1]New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ↑ Christopher Philip Hood. 2001. Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone's Legacy. (New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 041523283X), 70.

- ↑ D. Cripps, 1996. "Flags and Fanfares: The Hirnomaru Flag and the Kimigayo Anthem," in Goodman, Roger and Ian Neary, eds. 1996. Case Studies on Human Rights in Japan. (London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 1873410352), 81.

- ↑ Goodman and Refsing, 1996, 33.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 57.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002. 58.

- ↑ Gordon, 2003, 228.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 77-79.

- ↑ Robert Guillain. 1981. I saw Tokyo burning: An eyewitness narrative from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. (London, UK: J. Murray. ISBN 0385157010).

- ↑ Herbert Bix. 2001. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. (New York, NY: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060931302), 571-573.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 235-238.

- ↑ British Commonwealth Occupation Force 1946–51. Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 131-136.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002. 271.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Eiji, 2002, 522.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Frederick H. Gareau, 1961. "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany." The Western Political Quarterly 14(2):531.

- ↑ Note: A footnote in Gareau also states: "For a text of this decision, see Activities of the Far Eastern Commission. Report of the Secretary General, February, 1946 to July 10, 1947, Appendix 30, 85."

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 334-335.

- ↑ Gayl D. Ness, 1967. review of "Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World," by Barrington Moore, Jr. American Sociological Review 32(5):819.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 339-340.

- ↑ Edmundo Flores, 1970. "Issues of Land Reform." The Journal of Political Economy 78(4):901.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 518-519, 527-528.

- ↑ Asahi Shimbun Staff. 1972. The Pacific Rivals: A Japanese View of Japanese-American Relations. (New York, NY: Weatherhill. ISBN 9780834800700), 126.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 365.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 247.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 258.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 256.

- ↑ Dower. 1999. pg 325.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Bix. 2001. pg 585.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 326.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 562.

- ↑ John W. Dower. 1993. Japan in War and Peace. (New York, NY: The New Press. ISBN 1565842790), 11.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 511.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 512.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 46-47.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 90.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 54.

- ↑ Gordon, 2003. 229.

- ↑ Eiji, 2002, 69-71.

- ↑ Dower, 1999, 148. [2]googlebooks online. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ↑ Gordon W. Prange Collection 1945 - 1949. Library University of Maryland. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asahi Shimbun Staff. 1972. The Pacific Rivals: A Japanese View of Japanese-American Relations. New York, NY: Weatherhill. ISBN 9780834800700.

- British Commonwealth Occupation Force 1946–51. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- Bix, Herbert. 2001. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060931302.

- Cripps, D. 1996. "Flags and Fanfares: The Hinomaru Flag and the Kimigayo Anthem." In Goodman, Roger and Ian Neary, eds. 1996. Case Studies on Human Rights in Japan. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 1873410352.

- Dower, John W. 1999. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York, NY: Norton. ISBN 0393046869.

- Dower, John W. 1993. Japan in War and Peace. New York, NY: The New Press. ISBN 1565840674.

- Eiji, Takemae. 2002. Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-6247-2.

- Flores, Edmundo. 1970. "Issues of Land Reform." The Journal of Political Economy 78(4):890-905.

- Gareau, Frederick H. 1961. "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany." The Western Political Quarterly 14(2):517-534.

- Goodman, Roger, and Kirsten Refsing. 1992. Ideology and Practice in Modern Japan. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0415061024.

- Gordon, Andrew. 2003. A Modern History of Japan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195110609.

- Guillain, Robert. 1981. I saw Tokyo burning: An eyewitness narrative from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. London, UK: J. Murray. ISBN 0385157010.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. 2005. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674016939.

- Hood, Christopher Philip. 2001. Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone's Legacy. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 041523283X.

- Glossary: Birth of the Constitution of Japan. National Diet Library, Japan. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- Moore, Barrington. [1966] Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World, rev. ed. with new Forward. Boston: Beacon Press, 1993. ISBN 0807050733.

- Ness, Gayl D. 1967. Review of Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World, by Barrington Moore, Jr. American Sociological Review 32(5):818-820.

- Prange, Gordon W. At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story Of Pearl Harbor. Penguin, 1982. ISBN 0140157344.

- Sugita, Yoneyuki. 2003. Pitfall or Panacea - The Irony of US Power in Occupied Japan, 1945-1952. London, UK: Rutledge. ISBN 0415947529.

- Weisman, Steven R. 1990. "For Japanese, Flag and Anthem Sometimes Divided." New York Times.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- A sweet memory: My first encounter of an American soldier

- Gordon W. Prange Collection 1945 - 1949. Library University of Maryland.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.