Parthenon

The Parthenon (Greek: Παρθενώνας) is a temple of the Greek goddess Athena built in the fifth century B.C.E. on the Acropolis of Athens. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered one of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon, one of the most visited archaeological sites in Greece,[1] is regarded as an enduring symbol of ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy, and is one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. Its continued existence, however, depends on our choosing to use our advanced science and technology to preserve and protect it from dangers such as pollution.

Name

The origin of the Parthenon's name is unclear. According to Jeffrey M. Hurwit, the term "Parthenon" means "of the virgin" or "of the virgins," and seems to have originally referred only to a particular room of the Parthenon; it is debated which room this is, and how the room acquired its name. One theory holds that the "parthenon" was the room in which the peplos presented to Athena at the Panathenaic Festival was woven by the arrephoroi, a group of four young girls chosen to serve Athena each year.[2] Christopher Pelling asserts that Athena Parthenos may have constituted a discrete cult of Athena, intimately connected with, but not identical to that of Athena Polias. Research has revealed a shrine with altar pre-dating the Older Parthenon, respected by, incorporated, and rebuilt in the north pteron of the Parthenon [3] According to this theory, the name of Parthenon means the "temple of the virgin goddess," and refers to the cult of Athena Parthenos that was associated with the temple.[4] The epithet parthénos (Greek: παρθένος), whose the origin is also unclear,[5] meant "virgin, unmarried woman," and was especially used for Artemis, the goddess of wild animals, the hunt, and vegetation, and for Athena, the goddess of war, handicraft, and practical reason.[6] [7] [8] It has also been suggested that the name of the temple alludes to the virgins (parthenoi), whose supreme sacrifice guaranteed the safety of the city.[9] The first instance in which Parthenon definitely refers to the entire building is in the fourth century B.C.E. orator Demosthenes. In the fifth century building accounts, the structure is simply called ho neos ("the temple").

Design and construction

The first endeavor to build a sanctuary for Athena Parthenos on the site of the present Parthenon was begun shortly after the battle of Marathon (c. 490-488 B.C.E.) upon a massive limestone foundation that extended and leveled the southern part of the Acropolis summit. This building replaced a hekatompedon (meaning "hundred-footer") and would have stood beside the archaic temple dedicated to Athena Polias. The Older or Pre-Parthenon, as it is frequently referred to, was still under construction when the Persians sacked the city in 480 B.C.E. and razed the Acropolis.[10]

In the mid-fifth century B.C.E., when the Acropolis became the seat of the Delian League and Athens was the greatest cultural center of its time, Pericles initiated an ambitious building project which lasted the entire second half of the fifth century B.C.E. The most important buildings visible on the Acropolis today - that is, the Parthenon, the Propylaia, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike, were erected during this period. Parthenon was built under the general supervision of the sculptor Phidias, who also had charge of the sculptural decoration. The architects, Iktinos and Kallikrates, began in 447 B.C.E., and the building was substantially completed by 432, but work on the decorations continued until at least 431. Some of the financial accounts for the Parthenon survive and show that the largest single expense was transporting the stone from Mount Pentelicus, about 16 kilometers from Athens, to the Acropolis. The funds were partly drawn from the treasury of the Delian League, which was moved from the Panhellenic sanctuary at Delos to the Acropolis in 454 B.C.E.

Although the nearby Temple of Hephaestus is the most complete surviving example of a Doric order temple, the Parthenon, in its day, was regarded as the finest. The temple, wrote John Julius Norwich,

Enjoys the reputation of being the most perfect Doric temple ever built. Even in antiquity, its architectural refinements were legendary, especially the subtle correspondence between the curvature of the stylobate, the taper of the naos walls and the entasis of the columns.[11]

The stylobate is the platform on which the columns stand. It curves upwards slightly for optical reasons. Entasis refers to the slight tapering of the columns as they rise, to counter the optical effect of looking up at the temple. The effect of these subtle curves is to make the temple appear more symmetrical than it actually is.

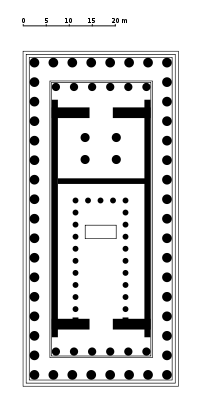

Measured at the top step, the dimensions of the base of the Parthenon are 69.5 meters by 30.9 meters (228.0 x 101.4 ft). The cella was 29.8 metres long by 19.2 metres wide (97.8 x 63.0 ft), with internal Doric colonnades in two tiers, structurally necessary to support the roof. On the exterior, the Doric columns measure 1.9 meters (6.2 ft) in diameter and are 10.4 meters (34.1 ft) high. The corner columns are slightly larger in diameter. The Parthenon had 46 outer pillars and 19 inner pillars in total. The stylobate has an upward curvature towards its center of 60 millimeters (2.36 in) on the east and west ends, and of 110 millimeters (4.33 in) on the sides. Some of the dimensions form the golden rectangle expressing the golden ratio[12] which is attributed to Pythagoras.[13]

The roof was covered with large overlapping marble tiles known as imbrices and tegulae.

Sculptural decoration

The Parthenon, an octostyle, peripteral Doric temple with Ionic architectural features, housed the chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos sculpted by Phidias and dedicated in 439/438 B.C.E. The decorative stonework was originally highly colored.[14] The temple was dedicated to the Athena at that time, though construction continued until almost the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 432. By the year 438, the sculptural decoration of the Doric metopes on the frieze above the exterior colonnade, and of the Ionic frieze around the upper portion of the walls of the cella, had been completed. The richness of the Parthenon's frieze and metope decoration is in agreement with the function of the temple as a treasury. In the opisthodomus (the back room of the cella) were stored the monetary contributions of the Delian League of which Athens was the leading member.

Metopes

The 92 metopes were carved in high relief, a practice employed until then only in treasuries (buildings used to keep votive gifts to the gods). According to the building records, the metope sculptures date to the years 446-440 B.C.E. Their design is attributed to the sculptor Kalamis. The metopes of the east side of the Parthenon, above the main entrance, depict the Gigantomachy (mythical battles between the Olympian gods and the Giants). The metopes of the west end show Amazonomachy (mythical battle of the Athenians against the Amazons).

The metopes of the south side—with the exception of the somewhat problematic metopes 13–20, now lost—show the Thessalian Centauromachy (battle of the Lapiths aided by Theseus against the half-man, half-horse Centaurs). On the north side of the Parthenon the metopes are poorly preserved, but the subject seems to be the sack of Troy.

Stylistically, the metopes present surviving traces of the Severe Style in the anatomy of the figures' heads, in the limitation of the corporal movements to the contours and not to the muscles, and in the presence of pronounced veins in the figures of the Centauromachy. Several of the metopes still remain on the building, but with the exception of those on the northern side, they are severely damaged. Some of them are located at the Acropolis Museum, others are in the British Museum and one can be seen at the Louvre Museum.

Frieze

The most characteristic feature in the architecture and decoration of the temple is the Ionic frieze running around the exterior walls of the cella. Carved in bas-relief, the frieze was carved in situ and it is dated in 442-438 B.C.E.

One interpretation is that it depicts an idealized version of the Panathenaic procession from the Dipylon Gate in the Kerameikos to the Acropolis. In this procession held every year, with a special procession taking place every four years, Athenians and foreigners were participating to honor the goddess Athena offering sacrifices and a new peplos (dress woven by selected noble Athenian girls called ergastines).

Another interpretation of the Frieze is based on Greek Mythology. This interpretation postulates that the scenes depict the sacrifice of Pandora, youngest daughter of Erechtheus to Athena. This human sacrifice was demanded by Athena to save the city from Eumolpus, king of Eleusis who had gathered an army to attack Athens.[15]

Pediments

Pausanias, the second century traveller, when he visited the Acropolis and saw the Parthenon, briefly described only the pediments (four entrances to the Parthenon) of the temple.

East pediment

The East pediment narrates the birth of Athena from the head of her father, Zeus. According to Greek mythology Zeus gave birth to Athena after a terrible headache prompted him to summon Hephaestus’ (the god of fire and the forge) assistance. To alleviate the pain he ordered Hephaestus to strike him with his forging hammer, and when he did, Zeus’ head split open and out popped the goddess Athena in full armor. The sculptural arrangement depicts the moment of Athena’s birth.

Unfortunately, the center pieces of the pediment were destroyed before Jacques Carrey created drawings in 1674, so all reconstructions are subject to conjecture and speculation. The main Olympian gods must have stood around Zeus and Athena watching the wondrous event with Hephaestus and Hera near them. The Carrey drawings are instrumental in reconstructing the sculptural arrangement beyond the center figures to the north and south.[16]

West pediment

The west pediment faced the Propylaia and depicted the contest between Athena and Poseidon during their competition for the honor of becoming the city’s patron. Athena and Poseidon appear at the center of the composition, diverging from one another in strong diagonal forms with the goddess holding the olive tree and the god of the sea raising his trident to strike the earth. At their flanks they are framed by two active groups of horses pulling chariots, while a crowd of legendary personalities from Athenian mythology fills the space out to the acute corners of the pediment.

The work on the pediments lasted from 438 to 432 B.C.E. and the sculptures of the Parthenon pediments are some of the finest examples of classical Greek art. The figures are sculpted in natural movement with bodies full of vital energy that bursts through their flesh, as the flesh in turn bursts through their thin clothing. The thin chitons allow the body underneath to be revealed as the focus of the composition. The distinction between gods and humans is blurred in the conceptual interplay between the idealism and naturalism bestowed on the stone by the sculptors.[17]

Athena Parthenos

The only piece of sculpture from the Parthenon known to be from the hand of Phidias[18] was the cult statue of Athena housed in the naos. This massive chryselephantine sculpture is now lost and known only from copies, vase painting, gems, literary descriptions, and coins.[19]

The most renowned cult image of Athens, the Athena Parthenos was featured on contemporary reliefs commemorating Athenian treaties and for the next century and a half on coins of Hellenistic monarchs avid to proclaim their Hellenic connections.[20] It is considered one of the greatest achievements of the most acclaimed sculptor of ancient Greece.

Treasury or Temple?

Architecturally, the Parthenon is clearly a temple, formerly containing the famous cult image of Athena by Phidias and the treasury of votive offerings. Since actual ancient Greek sacrifices always took place at an altar invariably under an open sky, as was in keeping with their religious practices, the Parthenon does not suit some definitions of "temple," as no evidence of an altar has been discovered. Thus, some scholars have argued that the Parthenon was only used as a treasury. While this opinion was first formed late in the nineteenth century, it has gained strength in recent years. The majority of scholarly opinion still sees the building in the terms noted scholar Walter Burkert described for the Greek sanctuary, consisting of temenos, altar and temple with cult image.[21]

Later history

The Parthenon replaced an older temple of Athena, called the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 B.C.E. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury, and for a time served as the treasury of the Delian League, which later became the Athenian Empire. In the sixth century C.E., the Parthenon was converted into a Christian church dedicated to the Virgin. After the Ottoman conquest, it was converted into a mosque in the early 1460s. On September 28, 1687, an Ottoman ammunition dump inside the building was ignited by Venetian bombardment. The resulting explosion severely damaged the Parthenon and its sculptures. In 1806, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin removed some of the surviving sculptures, with Ottoman permission. These sculptures, now known as the Elgin or Parthenon Marbles, were sold in 1816 to the British Museum in London, where they are now displayed. The Greek government is committed to the return of the sculptures to Greece, so far with no success.

Christian church

The Parthenon survived as a temple to Athena for close to a thousand years. It was certainly still intact in the fourth century C.E., but by that time Athens had been reduced to a provincial city of the Roman Empire, albeit one with a glorious past. Sometime in the fifth century C.E., the great cult image of Athena was looted by one of the Emperors, and taken to Constantinople, where it was later destroyed, possibly during the sack of the city during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 C.E.

Shortly after this, the Parthenon was converted to a Christian church. In Byzantine times it became the Church of the Parthenos Maria (Virgin Mary), or the Church of the Theotokos (Mother of God). At the time of the Latin Empire it became for about 250 years a Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady. The conversion of the temple to a church involved removing the internal columns and some of the walls of the cella, and the creation of an apse at the eastern end. This inevitably led to the removal and dispersal of some of the sculptures. Those depicting gods were either possibly re-interpreted according to a Christian theme, or removed and destroyed.

During Ottoman rule

In 1456, Athens fell to the Ottomans, and the Parthenon was converted again, this time into a mosque. Contrary to subsequent misconception, the Ottomans were generally respectful of ancient monuments in their territories, and did not willfully destroy the antiquities of Athens, though they had no actual program to protect them. However in times of war they were willing to demolish them to provide materials for walls and fortifications. A minaret was added to the Parthenon and its base and stairway are still functional, leading up as high as the architrave and hence invisible from the outside; but otherwise the building was not damaged further. European visitors in the seventeenth century, as well as some representations of the Acropolis hill testified that the building was largely intact.

In 1687, the Parthenon suffered its greatest blow when the Venetians under Francesco Morosini attacked Athens, and the Ottomans fortified the Acropolis and used the building as a gunpowder magazine. On September 26, a Venetian mortar, fired from the Hill of Philopappus, exploded the magazine and the building was partly destroyed.[22] Francesco Morosini then proceeded to attempt to loot sculptures from the now ruin. The internal structures were demolished, whatever was left of the roof collapsed, and some of the pillars, particularly on the southern side, were decapitated. The sculptures suffered heavily. Many fell to the ground and souvenirs were later made from their pieces. Consequently some sections of the sculptural decoration are known only from the drawings made by Flemish artist Jacques Carrey in 1674.[23] After this, much of the building fell into disuse and a smaller mosque was erected.

The eighteenth century was a period of Ottoman stagnation, as a result many more Europeans found access to Athens, and the picturesque ruins of the Parthenon were much drawn and painted, spurring a rise in philhellenism and helping to arouse sympathy in Britain and France for Greek independence. Amongst those early travelers and archaeologists were James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, who were commissioned by the Society of the Diletanti to survey the ruins of classical Athens. What they produced was the first measured drawings of the Parthenon published in 1787 in the second volume of Antiquities of Athens Measured and Delineated. In 1801, the British Ambassador at Constantinople, the Earl of Elgin, obtained a firman (permit) from the Sultan to make casts and drawings of the antiquities on the Acropolis, to demolish recent buildings if this was necessary to view the antiquities, and to remove sculptures from them. He took this as permission to collect all the sculptures he could find. He employed local people to detach them from the building itself, a few others he collected from the ground, and some smaller pieces he bought from local people. The detachment of the sculptures caused further irreparable damage to what was left of the building as some of the frieze blocks were sawn in half to lessen their weight for shipment to England.

Independent Greece

When independent Greece gained control of Athens in 1832, the visible section of the minaret was removed from the Parthenon and soon all the medieval and Ottoman buildings on the Acropolis were removed. However the image of the small mosque within the Parthenon's cella has been preserved in Joly de Lotbinière's Excursions Daguerriennes, published 1842: the first photograph of the acropolis.[24] The area became a historical precinct controlled by the Greek government. Today it attracts millions of tourists every year, who travel up the path at the western end of the Acropolis, through the restored Propylaea, and up the Panathenaic Way to the Parthenon, which is surrounded by a low fence to prevent damage.

Dispute over the Marbles

Today the Parthenon Marbles that Earl of Elgin removed are in the British Museum. Other sculptures from the Parthenon are now in the Louvre Museum in Paris, in Copenhagen, and elsewhere, but most of the remainder are in Athens, in the Acropolis Museum which still stands below ground level, a few meters to the south-east of the Parthenon, but will be soon transferred to a new building.[25] A few can still be seen on the building itself. The Greek government has been campaigning since 1983 for the British Museum sculptures to be returned to Greece.[26] The British Museum has steadfastly refused to return the sculptures and successive British governments have been unwilling to force the Museum to do so (which would require legislation).

Reconstruction

In 1975, the Greek government began a concerted effort to restore the Parthenon and other Acropolis structures. The project later attracted funding and technical assistance from the European Union. An archaeological committee thoroughly documented every artifact remaining on the site, and architects assisted with computer models to determine their original locations. In some cases, prior re-construction was found to be incorrect. Particularly important and fragile sculptures were transferred to the Acropolis Museum. A crane was installed for moving marble blocks; the crane was designed to fold away beneath the roof-line when not in use. The incorrect reconstructions were dismantled, and a careful process of restoration began. The Parthenon will not be restored to a pre-1687 state, but the explosion damage will be mitigated as much as possible, both in the interest of restoring the structural integrity of the edifice (important in this earthquake-prone region) and to restore the æsthetic integrity by filling in chipped sections of column drums and lintels, using precisely sculpted marble cemented in place. New marble is being used from the original quarry. Ultimately, almost all major pieces of marble will be placed in the structure where they originally would have been, supported as needed by modern materials.

Originally, various blocks were held together by elongated iron H pins that were completely coated in lead, which protected the iron from corrosion. Stabilizing pins added in the nineteenth century were not so coated and corroded. Since the corrosion product (rust) is expansive, the expansion caused further damage by cracking the marble. All new metalwork uses titanium, a strong, light, and corrosion resistant material.

Pollution hazards

An immediate problem facing the Parthenon is the environmental impact of the growth of Athens since the 1960s. Corrosion of its marble by acid rain and car pollutants has already caused irreparable damage to some sculptures and threatens the remaining sculptures and the temple itself. Over the past 20 years, the Greek government and the city of Athens have made some progress on these issues, but the future survival of the Parthenon does not seem to be assured.

Notes

- ↑ With 770.010 visitors according to 2003 statistics of the National Statistical Service of Greece, Acropolis of Athens was the most visited archaeological site in Greece, with Knossos in the second place with 633,903 visitors.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Hurwit. The Athenian Acropolis. (2000 Cambridge University Press), 161–163.

- ↑ Christopher Pelling. Greek Tragedy and the Historian. (1997 Oxford University Press), 169).

- ↑ " Parthenon" Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ Parthenon, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ Martin Bernal. Black Athena Writes Back-CL. (Duke University Press, 2001), 159

- ↑ J. G. Frazer. The Golden Bough 1900, online ed. [1], 18 Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Parthenos" Encyclopaedia Mythica [2] Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ↑ James Whitley. "Archaeology of Democracy: Classical Athens." The Archaeology of Ancient Greece. (2001 Cambridge University Press), 352

- ↑ Hurwit, "The Parthenon and the Temple of Zeus." in Periklean Athens and Its Legacy: Problems and Perspectives. (2005 University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292706227), 135

Venieri, Acropolis of Athens - History - ↑ John Julius Norwich, Great Architecture of the World, 2001, p.63

- ↑ Audrey M. Van Mersbergen, "Rhetorical Prototypes in Architecture: Measuring the Acropolis," Philosophical Polemic Communication Quarterly 46, (1998).

- ↑ Proclus ascribed the golden ratio to Pythagoras. It is also known that the Pythagoreans used the Pentagram which incorporates the golden ratio.

- ↑ Parthenon sculptures were colored blue, red and green Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ↑ Joan B. Connelly, "Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze." American Journal of Archaeology 100 (1996): 53–80.

- ↑ Thomas Sakoulas, Ancient Greece.org. accessdate 2007-05-31

- ↑ Thomas Sakoulas Ancient Greece.org. accessdate 2007-05-31

- ↑ Kenneth D. S. Lapatin. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2002), 63.

- ↑ Neda Leipen. Athena Parthenos: a reconstruction. (Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum, ASIN: B0006D2JGE, 1972).

- ↑ Hector Williams, "An Athena Parthenos from Cilicia" Anatolian Studies 27 (1977, 105-110), 108f.

- ↑ Walter Burkert. Greek Religion. (Harvard University Press, 1985), 84

- ↑ Theodor E. Mommsen, "The Venetians in Athens and the Destruction of the Parthenon in 1687." American Journal of Archaeology 45 (4) (Oct. - Dec., 1941): 544–556

- ↑ Theodore Robert Bowie, D. Thimme, The Carrey Drawings of the Parthenon Sculptures. (Indiana University Press, 1971. ISBN 0253313201)

- ↑ Jenifer Neils. The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 336 – the picture was taken in October 1839

- ↑ Greek Premier Says New Acropolis Museum to Boost Bid for Parthenon Sculptures, International Herald Tribune.

* "Parthenon". Encyclopaedia Britannica. - ↑ Greek Premier Says New Acropolis Museum to Boost Bid for Parthenon Sculptures, International Herald Tribune.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Printed sources

- Bernal, Martin. Black Athena Writes Back-CL: Martin Bernal Responds to His Critics. Duke University Press, 2001. ISBN 0822327171

- Bowie, Theodore Robert. and D. Thimme, The Carrey Drawings of the Parthenon Sculptures. Indiana University Press, 1971. ISBN 0253313201

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Harvard University Press, 1985 ISBN 0674362810

- Connelly, Joan B., 1996 January "Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze." American Journal of Archaeology 100 (1).

- Frazer, Sir James George. "The King of the Woods." in The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. [1900] 1998 Oxford University Press, ISBN 0192835416 online 1900 ed. [3].Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present. 2000 Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521428343

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M., Jerome Jordan Pollitt and Judith M. Barringer, (eds) "The Parthenon and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia." in Periklean Athens and Its Legacy: Problems and Perspectives. 2005 University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292706227

- Lapatin, Kenneth D.S. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0198153112

- Leipen, Neda. Athena Parthenos: a reconstruction. Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum, 1972. ASIN: B0006D2JGE

- Neils, Jenifer. The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. 2005 Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521820936

- "Parthenon" Encyclopaedia Britannica 2002.

- "Parthenos" Encyclopaedia Mythica [4] Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Pelling, Christopher. "Tragedy and Religion: Constructs and Readings." Greek Tragedy and the Historian. 1997 Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198149875

- Whitley, James. "Archaeology of Democracy: Classical Athens." The Archaeology of Ancient Greece. 2001 Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521627338

Online sources

- Greek Premier Says New Acropolis Museum to Boost Bid for Parthenon Sculptures. [5] International Herald Tribune 2006-10-09. accessdate 2007-04-23

- Ioanna Venieri Acropolis of Athens - History Οδυσσεύς Acropolis of Athens accessdate 2007-05-04

- Parthenon[6] accessdate 2007-05-05 Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Talks Due on Elgin Marbles Return [7] BBC News. 2007-04-21 accessdate 2007-04-23

Further reading

- Beard, Mary. 2003. The Parthenon. Harvard University. ISBN 0-674-01085-X

- Cosmopoulos, Michael. 2004. The Parthenon and its Sculptures. Cambridge University: 2004. ISBN 0-521-83673-5

- Holtzman, Bernard (2003). L'Acropole d'Athènes : Monuments, Cultes et Histoire du sanctuaire d'Athèna Polias (in French). Paris: Picard. ISBN 2-7084-0687-6.

- King, Dorothy. 2006. The Elgin Marbles. Random House Adult Trade Publishing Group. ISBN 0-09-180013-7

- Papachatzis, Nikolaos D. 1974. Pausaniou Ellados Periegesis- Attika. Athens.

- Tournikio, Panayotis. 1996. Parthenon. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-6314-0

- Traulos, Ioannis N. 1960. I Poleodomike ekselikses ton Athinon. Athens. ISBN 960-7254-01-5

- Woodford, Susan. 1981. The Parthenon. Cambridge University. ISBN 0-521-22629-5

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- The Acropolis of Athens: The Parthenon (official site with a schedule of its opening hours, tickets and contact information)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.