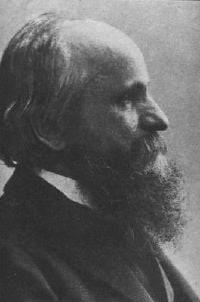

Alexius Meinong

Alexius Meinong (July 17, 1853 - November 27, 1920) was an Austrian philosopher who taught at the University of Graz from 1878 until his death in 1920. He was the first to carry out systematic experiments in Gestalt psychology. In 1894 he established the Graz psychological institute, and also founded the Graz School of experimental psychology.

Meinong made significant contributions to psychology, epistemology, value theory, ethics, probability theory and aesthetics, but he is most noted for his "Theory of Objects" (Über Gegenstandstheorie, 1904). It was based around the observation that it is possible to think about something, such as a golden mountain, even though that object does not exist. Meinong defined “objects” as things which can be thought about, whether they are actual material objects or complex mental objects, such as concepts, relations, abstractions, imaginings, wholes, and intellectual phenomena. He claimed that it had been mistakenly supposed that, when a thought has a non-existent object, there is really no object distinct from the thought. Meinong also researched the role of emotions in mental phenomena, and developed a theory of aesthetics based on the Theory of Objects.

Life

Alexius Meinong Ritter von Handschuchsheim, was born in Lemberg, Austria (now L'viv in Ukraine), on July 17, 1853 to a Catholic noble family. He studied at the Academic Gymnasium, Vienna and later the University of Vienna where he studied history and philosophy as a pupil of Franz Brentano from 1875 to 1878. He was professor and Chair of Philosophy at the University of Graz, where he taught from 1878 until his death in 1920. In 1894 he founded the Graz psychological institute, and also founded the Graz School of experimental psychology, the first laboratory for experimental psychology in Austria. He was the first to carry out systematic experiments in Gestalt psychology, and supervised the promotion of Christian von Ehrenfels (founder of Gestalt psychology), as well as the habilitation of Alois Höfler and Anton Oelzelt-Newin. He died in Graz, Austria, on November 27, 1920.

Thought and Works

Meinong made significant contributions to psychology, epistemology, value theory, ethics, probability theory and aesthetics, but he is most noted for his Theory of Objects (Über Gegenstandstheorie, 1904) which grew out of his work on intentionality and his belief in the possibility of intending nonexistent objects. Meinong’s views on existence are also controversial in the field of philosophy of language.

Theory of Objects (Gegenstandstheorie)

The Theory of Objects is based around the observation that it is possible to think about something, such as a golden mountain, even though that object does not exist. Meinong defines “objects” as things which can be thought about, whether they are actual material objects or complex mental objects, such as concepts, relations, abstractions, imaginings, wholes, and intellectual phenomena. There are many objects of thought that do not actually exist, and yet these nonexistent objects are constituted in such a way that they can be thought about in the same way as objects that do exist. Even “unthinkable” concepts, such as infinity, can be thought of as being “unthinkable.” Every possible object of thought has a certain nature, or character (Sosein); being (Sein) is only a part of the nature of some objects. Mental objects possessing the characteristic of being made up only an infinitesimal part of all the objects of knowledge.

Meinong believed that traditional metaphysics dealt only with those objects that had being or subsistence as part of their character, and tended to “neglect those objects that have no kind of being at all,” and that therefore a more general theory of objects was needed. He observed that `prejudice in favor of the existent' (des Wirklichen), had led people to suppose mistakenly that, when a thought has a non-existent object, there is really no object distinct from the thought.

Meinong suggested two sources of insight for the study of objects, mathematics and the rules of grammar. Mathematics deals with many concepts, such as negative numbers, that exist in the mind but not in the real world. In grammar, we can see that the meaning of a noun or verb can be altered and even negated by the addition of certain adjectives and adverbs; for example, the adjective “square,” if applied to the noun “circle” results in an impossible object.

Like Franz Brentano, Meinong considered the basic feature of mental states to be “intentionality,” or the direction of attention to “objects.” He distinguished two elements in every experience of the objective: the “content” of the experience, which distinguishes one object from another; and the “act” by which the experience approaches its object. The “acts” involved in thinking about a real object, such as a table, are different from the acts involved in reading a book and thinking about a fictional character such as Sherlock Holmes.

Aesthetics

Meinong devoted considerable effort to investigating the nature of the emotions and their relation to intellectual phenomena. He divided mental phenomena into two classes: serious, genuine (Ernstgefühle,, bona fide) phenomena and “phantasy phenomena” (Scheinegefühle). A phantasy presentation isdistinguished from a bona fide presentation by the absence of belief in the existence of the object being presented. A bona fide emotion arises from a state of affairs which is believed to be real, while a phantasy emotion arises from a state of affairs which is known not to really exist. The bona fide and phantasy emotions share certain qualities, such as sadness or excitement, but differ vastly in their psychological consequences. For example, the sadness evoked by the death of character in a movie soon disappears, leaving little or no lasting impression, while sadness at the death of a loved one lingers and has deep psychological consequences.

Art, literature and music create circumstances that evoke emotions similar to those which would be experienced in real-life situations, yet the person experiencing the emotions is aware that those circumstances are deliberately created. The act of experiencing phantasy emotions involves willing participation, while bona fide emotions are usually involuntary acts. A work of art is an artifact constructed according to recognized principles to serve as a catalyst in evoking enjoyable emotions. Meinong’s disciple Stephan Witasek (1870 – 1915), who spent many hours playing music with Meinong, developed a detailed theory of aesthetic phenomena based on the theory of objects.

Influence

Bertrand Russell respected Meinong's work and undertook a serious study of it; it was in response to the theory of objects that he developed his own theory of descriptions, first elaborated in his famous essay "On Denoting." Russell questioned the validity of the principle that, because a phrase such as “the golden mountain” could serve as the subject of a sentence, it denoted a reality. Russell characterized such phrases as “descriptions,” or “incomplete symbols,” rather than “names,” and questioned whether they had any real meaning when taken by themselves. He contended that sentences which had such descriptions as grammatical subjects could be restated in a way that would show that they were not the real logical subjects.

Meinongians such as Terence Parsons and Roderick Chisholm established the consistency of a Meinongian theory of objects, and others such as Karel Lambert) have defended the usefulness of such a theory.

Before entering upon details, I wish to emphasise the admirable method of Meinong's researches, which, in a brief epitome, it is quite impossible to preserve. Although empiricism as a philosophy does not appear to be tenable, there is an empirical manner of investigating, which should be applied in every subject-matter. This is possessed in a very perfect form by the works we are considering. A frank recognition of the data, as inspection reveals them, precedes all theorising; when a theory is propounded, the greatest skill is shown in the selection of facts favorable or unfavorable, and in eliciting all relevant consequences of the facts adduced. There is thus a rare combination of acute inference with capacity for observation. The method of philosophy is not fundamentally unlike that of other sciences : the differences seem to be only in degree. The data are fewer, but are harder to apprehend; and the inferences required are probably more difficult than in any other subject except mathematics. But the important point is that, in philosophy as elsewhere, there are self-evident truths from which we must start, and that these are discoverable by the process of inspection or observation, although the material to be observed is not, for the most part, composed of existent things. Whatever may ultimately prove to be the value of Meinong's particular contentions, the value of his method is undoubtedly very great; and on this account if on no other, he deserves careful study. [1]

Major Publications

Books

- Meinong, A. (1885). Über philosophische Wissenschaft und ihre Propädeutik

- Meinong, A. (1894). Psychologisch-ethische Untersuchung zur Werttheorie

- Meinong, A., ed. (1904). Untersuchung zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie

- Meinong, A. (1910). Über Annahmen, 2nd ed.

- Meinong, A. (1915). Über Möglichkeit und Wahrscheinlichkeit

- Meinong, A. (1917). Über emotionale Präsentation

Articles

- Meinong, A. "Hume Studien I. Zur Geschichte und Kritik des modernen Nominalismus." Sitzungsbereiche der phil.-hist. Classe der kais. Akademie der Wissenschaften 78 (1877): 185-260.

- Meinong, A. "Hume Studien II. Zur Relationstheorie," in Sitzungsbereiche der phil.-hist. Classe der kais. Akademie der Wissenschaften, 101 (1882): 573–752.

- Meinong, A. "Zur psychologie der Komplexionen und Relationen." Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane II (1891): 245–265.

- Meinong, A. "Über Gegenstände höherer Ordnung und deren Verhältniss zur inneren Wahrnehmung." Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane 21, (1899): 187-272.

Books together with other authors

- Höfler, A. and A. Meinong. Philosophische Propädeutik. Erster Theil: Logik. Vienna: F. Tempsky / G. Freytag, 1890.

Posthumously edited works

- Haller, R., R. Kindinger, and R. Chisholm, editors, Gesamtausgabe, 7 vols., Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft, 1968-1978.

- Meinong, A. Philosophenbriefe, ed. R. Kindinger, Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1965.

Notes

- ↑ Bertrand Russell, "Meinong's theory of complexes and assumptions." Mind (1904) reprinted in: Bertrand Russell - Essays in analysis - Edited by Douglas Lackey - (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1973): 22-23.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Books

- Albertazzi, L., D. Jacquette, and R. Poli, eds. The School of Alexius Meinong. Ashgate: Aldershot, 2001. ISBN 1840143746 ISBN 9781840143744

- Chisholm, Roderick M. Brentano and Meinong studies. Studien zur österreichischen Philosophie, Bd. 3. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1982. ISBN 0391023470 ISBN 9780391023475

- Findlay, J. N. Meinong's Theory of Objects and Values, 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

- Grossman, R. Meinong. London: Routledge, Boston: Paul Kegan, 1974. ISBN 0710078315 ISBN 9780710078315

- Haller, R., editor Jenseits von Sein und Nichtsein. Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1972.

- Lindenfeld, D. F. The Transformation of Positivism: Alexius Meinong and European Thought, 1880-1920. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980.

- Rollinger, R. D. "Meinong and Husserl on abstraction and universals: from Hume studies I to Logical investigations II." Studien zur Österreichischen Philosophie, Bd. 20. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1993. ISBN 9051835736 ISBN 9789051835731 ISBN 9789051835731 ISBN 9051835736

Articles

- Chrudzimski, A. "Abstraktion und Relationen beim jungen Meinong." Meinong Studies (2005): 7–62.

- Dölling, E. "Eine semiotische Sicht auf Meinongs Annahmenlehre." Meinong Studies (2005): 129–158.

- Kenneth, B. "Meinong’s Hume Studies. Part I: Meinong’s Nominalism." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 30 (1970): 550–567.

- __________. "Meinong’s Hume Studies. Part II: Meinong’s Analysis of Relations." in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 31 (1971): 564–584.

- Rollinger, R. D. "Meinong and Brentano." Meinong Studies (2005): 159–197.

- Schermann, H. "Husserls II. Logische Untersuchung und Meinongs Hume-Studien I. In (Haller, 1972): 103–116.

- Schramm, A., editor Meinong Studies - Meinong Studien I, Ontos Verlag. (2005).(yearly periodical)

External links

All links retrieved July 20, 2023.

- Alexius Meinong's Theory of Objects, Excerpts from several sources on the subject. The site maintained by Raul Corazzon, Formalontology TM.

- Ernst Mally, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. A representative philosopher of Meinong's School.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.