Amun (also spelled Amon, Amen; Greek: Ἄμμων Ammon, and Ἅμμων Hammon; Egyptian: Yamanu) was a multifaceted deity whose cult originated at Thebes, in the Upper Kingdom of classical Egypt. The god, whose name literally means "Hidden One," fulfilled various roles throughout Egyptian religious history, including creator god, fertility god, and patron of human rulers. When the Theban pharaohs unified the country during the New Kingdom period (1570–1070 B.C.E.), their favored deity became the subject of a national cult, eventually becoming syncretically merged with Ra (as Amun-Ra). After the dissolution of the fragile alliance between North and South, Amun gradually faded into relative obscurity, eclipsed by the increasingly popular veneration of Osiris, Horus, and Isis.

Amun in an Egyptian Context

| Amun in hieroglyphs | ||||

|

As an Egyptian deity, Amun belonged to a religious, mythological and cosmological belief system that developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to around 525 B.C.E.[1] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[2] The cults were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[3] Yet, the Egyptian gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “If we compare two of [the Egyptian gods] … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[4] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanent—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[5] Thus, those Egyptian gods who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Furthermore, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e., the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[6]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely defined by the geographical and calendrical realities of its believers' lives. The Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[7] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[8] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

Etymology

Amun's name is first attested to in Egyptian records as imn, which can be translated as "the Hidden (One)."[9] Since vowels were not written in Egyptian hieroglyphics, Egyptologists, in their hypothetical reconstruction of the spoken language, have argued that it would have originally been pronounced *Yamānu (yah-maa-nuh). The name survives, with unchanged meaning, as the Coptic Amoun, the Ethopian Amen, and the Greek Ammon.[10]

Some scholars have noted a strong linguistic parallel between the names of Amun (/Amen) and Min, an ancient deity who shared many areas of patronage and influence with his more popular contemporary. This veracity of this potential identification is bolstered by the fact that, historically speaking, the cult of Amun did supplant the worship of Min, especially in the area around Thebes (from whence it originated).[11]

Development of the Cult of Amun

As with many Egyptian deities, the cult of Amun (and the myths associated with it) developed through a long process of syncretism and theological innovation, both of which were tempered by the political fortunes of the cult's home region. While the understandings discussed below can broadly be divided into historical periods, it should be noted that the depictions of the god (unless otherwise noted) were cumulative. For example, Amun's later association with fertility seems to have supplemented (rather than overriding) his previous characterizations as a creator god and a royal patron.

Early cult - Amun as Creator God and patron of Thebes

Amun was, to begin with, the local deity of Thebes, when it was an unimportant town on the east bank of the river, about the region now occupied by the Temple of Karnak. Already characterized as the "Hidden One," the god was identified with the wind —an invisible but immanent presence in the region[12] — and also with the "hidden and unknown creative power which was associated with the primeval abyss [that predated the creation of this world]."[13] In this context, he (along with his female counterpart/consort Amunet) is mentioned in the Pyramid Texts, a compilation of inscriptions from the Old Kingdom period (268–2134 B.C.E.):

- Thy established-offering is thine, O Niw (Nun) together with Nn.t (Naunet),

- ye two sources of the gods, protecting the gods with their (your) shade.

- Thy established-offering is thine, O Amūn together with Amūnet,

- ye two sources of the gods, protecting the gods with their (your) shade.[14]

Describing this earliest mention of the deity, Budge notes that the explicit parallel between Nun/Naunet and Amun/Amunet (the former representing the primordial void) indicates that "the authors and editors of the Pyramid Texts assigned great antiquity to their existence."[15]

By the First Intermediate Period (2183-2055 B.C.E.), these beliefs were further elaborated, with the god coming to be interpreted as the creator of the universe (and, resultantly, as the creator of the celestial pantheon).[16] These developments are well summarized by Geraldine Pinch:

- Amun tended to be the subject of speculative theology rather than mythical narratives, but he did play a role in the creation myths of Hermopolis [an Upper Kingdom city relatively close to Thebes]. One of his incarnations was as the Great Shrieker, a primeval goose whose victory shout was the first sound. In some accounts, this primeval goose laid the "world egg;" in others, Amun fertilized or created this egg in his ram-headed serpent form known as Kematef[17] ("He who has completed his moment"). The temple of Medinet Habu in western Thebes was sometimes identified as the location of this primal event. A cult statue of the Amun of Karnak regularly visited this temple [during festival processions] to renew the process of creation.[18]

During this age, Amun was also assigned a female companion (aside from Amunet, who is better characterized as the god's own female aspect). Given his increasing identification with the creation of the cosmos, it was logical that he be united with Mut, a popular mother goddess of the Theban region. Within the context of this new family, he was thought to have fathered a son: either Menthu, a local war-god who became subordinate to him, or Khons, a lunar deity.[19]

The increasing importance of Amun can be strongly tied to the political fortunes of the Theban nome during this period of the Egyptian dynastic history. Most specifically, the eleventh dynasty (ca. 2130-1990 B.C.E.) was founded by a family from the area around Thebes itself, which thereby catapulted their favored deities into national prominence. The name of Amun came to be incorporated in the monikers of many rulers from this dynasty, such as Amenemhe (founder of the twelfth dynasty (1991-1802 B.C.E.)), whose name can be literally translated as "Amun is preeminent" or "The god Amon is First." The honors accorded to the god led to an increased level of expenditure at his various cult centers, most notably at the Temple of Karnak, which became one of the most well-appointed in the kingdom.[20]

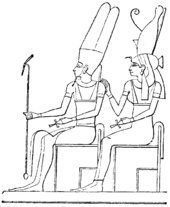

In this phase of the cult's development, Amun was primarily depicted in human form, seated on a throne, wearing a plain circlet from which rise two straight parallel plumes, possibly symbolic of the tail feathers of a bird, a reference to his earliest characterization as a wind god. Two main types are seen: in the one he is seated on a throne, in the other he is standing, ithyphallic, holding a scourge, precisely like Min, the god of Coptos and Chemmis (Akhmim)—a god whose association with Amun is discussed above.

Rise to national prominence

When the Theban royal family of the seventeenth dynasty drove out the Hyksos, Amun, as the god of the royal city, was again prominent. Given the oppression of the Egyptians under their Hyksos rulers, their victory (which was attributed to the supreme god Amun) was seen as the god's championing of the less fortunate. Consequently, Amun came to be seen as a benevolent defender of the disadvantaged, and came to be titled Vizier of the Poor.[21] Indeed, as the fortunes of these Theban dynasties were extended, Amun, their patron god, came to be associated with the office of the ruler. For instance, in "his chief cult temple at Karnak in Thebes, Amun, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, ruled as a divine pharaoh."[22]

However, it was not until the expansionistic military successes of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1292 B.C.E.) that Amun began to assume the proportions of a universal god for the Egyptians, eclipsing (or becoming syncretized with) most other deities and asserting his power over the gods of foreign lands. At this time, the Pharaohs credited all their successful enterprises to the god, which led them to lavish their wealth and captured spoil on his temples.[23]

Sun God

| Amun-Ra in hieroglyphs | |||||

|

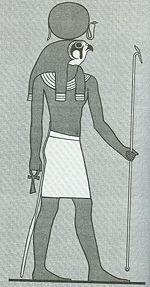

As Amun's cult spread throughout the empire, the Hidden One became identified with Ra, the sun god worshiped as lord of the cosmos in the Lower Kingdom. This identification led to a merger of identities, with the two deities joined into the composite form Amun-Ra. As Ra had been the father of Shu, and Tefnut, and the remainder of the Ennead (paralleling Amun's parentage of the Ogdoad), Amun-Ra was identified as the father of all Egyptian gods. This merger also saw Amun-Ra adopting the role of sun god, with Ra as the visible aspect of the sun and Amun as the hidden aspect (representing the seeming disappearance of the solar disc at night).

Throughout the New Kingdom period (1570–1070 B.C.E.), Amun-Ra was chief deity of the Egyptian religious system, a wide-spread devotional adoration that was even attested to in the names of monarchs, from Amenhotep ("Amun is Satisfied") to Tutankhamun ("the living image of Amun"). These rulers were also associated with the god through a popular myth that they were each conceived following a mystical union between their mothers and Amun.[24] Though the worship of the god was briefly halted under Akhenaten, it is still fair to say that it was the single most important cult in Egypt for over five hundred years.[25]

Fertility God

Amun also came to be associated with various ram-headed deities that were popular in Egypt (and surrounding areas) at the time. Indeed, his most frequent and celebrated incarnation was the woolly sheep with curved ("Ammon") horns (as opposed to the oldest native breed with long horizontal twisted horns and hairy coat, sacred to Khnum or Chnumis). In this guise, he was worshiped as a fertility god, both in Egypt and in recently conquered Nubia (Kush), where he incorporated the identity of their chief deity.

Given their association with fertility, Amun also began to absorb the identity of Min (a god representing sexual potency), becoming Amun-Min. This association with virility led to Amun-Min gaining the epithet Kamutef, meaning "Bull of his mother": an "epithet that suggests both that the god was self-engendered — meaning that he begot himself on his mother, the cow who personified the goddess of the sky and of creation—and also conveys the sexual energy of the bull [or ram] which, for the Egyptians was a symbol of strength and fertility par excellence."[26]

Decline

Though the cult of Amun remained a significant social force throughout the Twentieth Dynasty (1190-1077 B.C.E.), it gradually started to fade in importance during the social upheaval that followed. As the sovereignty of the central leadership weakened, the division between Upper and Lower Egypt began to reassert itself; this led to great decrease in the importance of Thebes (and all deities associated with the city). Indeed, Thebes would have rapidly decayed had it not been for the piety of the kings of Nubia towards Amun, whose worship had long prevailed in their country. However, in the rest of Egypt, the popularity of his cult was rapidly overtaken by the less divisive cult of the Osiris and Isis, which had not been associated with the reviled Akhenaten. Thus, his identity became first subsumed into Ra (Ra-Herakhty), who still remained an identifiable figure in the Osiris cult, but ultimately, became merely an aspect of Horus.[27]

This decline is poignantly depicted in Budge's encyclopedic survey The Gods of the Egyptians:

- When the last Rameses was dead the high-priest of Amen-Ra became king of Egypt almost as a matter of course, and he and his immediate successors formed the XXIst Dynasty, or the Dynasty of the priest-kings of Egypt. Their chief aim was to maintain the power of their god and of their own order, and for some years they succeeded in doing so; but they were priests and not warriors and their want of funds became more and more pressing, for the simple reason that they had no means of enforcing the payment of tribute by the peoples and tribes who, even under the later kings bearing the name of Rameses, acknowledged the sovereignty of Egypt. Meanwhile the poverty of the inhabitants of Thebes increased rapidly, and they were not only unable to contribute to the maintenance of the acres of temple buildings and to the services of the god, but found it difficult to obtain a living. … Notwithstanding their growing poverty and waning influence the priests in no way abated the pretensions of their god or of themselves, and they continued to proclaim the glory and power of Amen-Ra in spite of the increasing power of the Libyans in the Delta.[28]

In areas outside of Egypt, where the Egyptians had previously brought the worship of Amun, the decline in the god's prestige was neither so precipitous nor so dire. In Nubia, where his name was pronounced Amane, he remained the national god, with priests at Meroe and Nobatia regulating the affairs of government, selecting kings, and directing military expeditions via oracular knowledge. According to Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (90 to 21 B.C.E.), they were even able to compel kings to commit suicide, although their reign of terror ended in the third century B.C.E., when Arkamane [Ergamenes], a Kushite ruler, ordered that they be slain.[29] Likewise, in Ancient Libya there remained a solitary oracle of Amun at the oasis of Siwa, in the heart of the Libyan desert. Such was its reputation among the Greeks that Alexander the Great journeyed there after the battle of Issus, in order to be acknowledged as the son of Amun.[30] Finally, during the Hellenistic occupation of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Amun came to be syncretistically identified with Zeus—a logical enough choice, given the affiliations and realms of patronage shared by both deities.[31]

Derived terms

Several extant English words have been derived from the name of Amun (via the Greek form "Ammon"), including ammonia and ammonite. Ammonia, as a chemical compound, was given its name by Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman in 1782. He chose "ammonia" because he had obtained "the gas … from sal ammoniac, salt deposits containing ammonium chloride found near temple of Jupiter Ammon (from Egyptian God Amun) in Libya, from Gk. ammoniakon "belonging to Ammon."[32] The ammonites, an extinct class of cephalopods, had spiral shells resembling a ram's horns. As a result, the term was "coined by Bruguière from [the Latin] (cornu) Ammonis "horn of Ammon," the Egyptian god of life and reproduction, who was depicted with ram's horns, which the fossils resemble."[33] Likewise, there are two symmetrical regions of the hippocampus called the cornu ammonis (literally "Amun's Horns"), due to the horned appearance of the dark and light bands of cellular layers.[34]

Notes

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" Adolf Erman. A handbook of Egyptian religion, Translated by A. S. Griffith. (London: Archibald Constable, 1907), 203, it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition, according to Geraldine Pinch. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428), 31-32.

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god. Dimitri Meeks and Christine Meeks-Favard. Daily life of the Egyptian gods, Translated from the French by G. M. Goshgarian. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158), 34-37.

- ↑ Henri Frankfort. Ancient Egyptian Religion. (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772), 25-26.

- ↑ Christiane Zivie-Coche. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E., Translated from the French by David Lorton. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X), 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Jan Assmann. In search for God in ancient Egypt, Translated by David Lorton. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293), 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile. James Henry Breasted. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454), 8, 22-24.

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

- ↑ As A.E. Wallis Budge. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. reprint ed. (New York: Dover Publications, 1969. Vol. II), 2, notes, "The word or root amen certainly means 'what is hidden,' 'what is not seen,' 'what cannot be seen,' and the like, and this fact is proved by the scores of examples which may be collected from texts of all periods. In hymns to Amen we often read that he is 'hidden to his children,' and 'hidden to gods and men'.

- ↑ Pinch, 100; Wilkinson, 92; W. Max Muller and Kaufmann Kohler, "Amon" in the Jewish Encyclopedia, retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ See, for example, G. A. Wainwright's "The Origin of Amun," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 49 (Dec. 1963): 21-23. 22.

- ↑ Pinch, 100.

- ↑ Budge, 1969, Vol. II., 2.

- ↑ Pyramid Texts 446a-446d. Accessible online at: [1]sacred-texts.com.

- ↑ Budge, 1969, Vol. II, 1-2.

- ↑ More specifically, Amun, at least in the context of his Theban worshipers, came to be titled "father of the gods," and was understood to precede the other gods of the Ogdoad, although remaining one of them (Wilkinson, 92-93).

- ↑ The ram form of the god, with its associated connotations of fertility, will be discussed in greater detail below.

- ↑ Pinch, 101.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 92; Pinch, 100.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 92; Budge (1969), Vol. II, 3-4. Zivie-Coche, 75-77. See also Brian Brown's The Wisdom of Egypt, 1923 (p. 119). Accessed online at: sacred-texts.com.

- ↑ F. Charles Fensham, "Widow, Orphan, and the Poor in Ancient near Eastern Legal and Wisdom Literature," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2 (April 1962), 129-139. 133.

- ↑ Pinch, 100; Budge (1969), Vol. II, 4. This association with leadership is attested to in an inchoate form in the Pyramid Texts, where the office of the human ruler is metonymically described as "the throne of Amūn" (see Pyramid Texts 1540b).

- ↑ Budge (1969), Vol. II, 4-5.

- ↑ Pinch, 101.

- ↑ Budge (1969), Vol. II, 4-7; Pinch, 101-102; Wilkinson, 92-95.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 93. See also G. A. Wainwright, "Some Aspects of Amun," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 20 (3/4) (November 1934): 139-153, passim, for an excellent overview of the characterization of Amun as ram deity.

- ↑ Budge (1969), Vol. II, 12-13; Wilkinson, 95-97. The subordination of Amun to Horus is described in Samuel Sharpe's Egyptian Mythology and Egyptian Christianity (London: J.R. Smith, 1863). 87. Accessible online at sacred-texts.com. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ↑ Budge, 1969, Vol. II, 12-13.

- ↑ Erman, 197-198; Wilkinson, 97.

- ↑ Pinch, 101; Erman, 196.

- ↑ Pinch, 101; Wilkinson, 97. See also: W. Max Muller and Kaufmann Kohler, "Amon" in the Jewish Encyclopedia, retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Ammonia" in the Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Ammonite" in the Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ↑ Online Medical Dictionary "cornu ammonis". Retrieved August 14, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt, Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Brown, Brian. (1923) The Wisdom of Egypt. accessed at The Wisdom of Egypt. sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis, translator. The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at [2]. sacred-texts.com.

- __________. translator. The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- __________. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. reprint ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- __________. Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- __________. The Rosetta Stone. (1893) 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dennis, James Teackle, translator. The Burden of Isis. 1910. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dunand, Françoise, and Christiane Zivie-Coche. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E., Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion, Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Fensham, F. Charles, "Widow, Orphan, and the Poor in Ancient near Eastern Legal and Wisdom Literature," Journal of Near Eastern Studies 21 (2) (April 1962): 129-139.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. L., and Herbert Thompson, translators. The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Klotz, David. Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple. (Yale Egyptological Studies) New Haven: Yale Egyptological Seminar, 2006. ISBN 0974002526.

- Larson, Martin A. The Story of Christian Origins. J.J. Binns, 1977. ISBN 0883310902.

- Meeks, Dimitri, and Christine Meeks-Favard. Daily life of the Egyptian gods, Translated from the French by G. M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B., translator. The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E., ed. Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Sharpe, Samuel. Egyptian Mythology and Egyptian Christianity. London: J.R. Smith, 1863. Accessible online at [3]. sacred-texts.com. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- Wainwright, G. A., "The Origin of Amun," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 49 (Dec. 1963): 21-23.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.