Anglo-Asante Wars

The Anglo-Asante (Ashanti) Wars were four conflicts between the Asante Empire in the Akan interior of what is now Ghana and the British in the nineteenth century. The first war (1823 and 1831), seen by the British as part of their anti-slavery campaign, saw the British suffer a defeat. The second war, 1863-1864, ended in a stalemate. By 1874, when the third war ended in a peace-treaty, the British had claimed the rest of the Gold Coast as a Crown Colony, with Accra as its capital from 1877. The fourth war, 1894-1896, ended in a British victory. The Asante were forced to sign a treaty of protection; the Ashantehene (King of all Asante) and other leaders, were exiled. After a failed revolt in 1900, led by Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen-Mother, Asante territory was finally annexed as part of the Crown Colony.

The British were protecting the coastal people, primarily Fante and the inhabitants of Accra, from Asante incursions. In 1806 the British ended slavery on the Gold Coast. This bankrupted the (British) African Company of Merchants who owned the slave forts along the coast. It also affected the Asante economy which was dependent on the slave trade. At its height, 10,000 slaves a year were being exported from the area. The British took over the forts and extended their influence into the interior in their campaign against slavery. They were also concerned that the Ashanti were still involved in slave trading. Thus the two sides came to blows. Another dimension of the conflict was the imperial rivalry between the British who supported the Fante and the Dutch who supported the Asente. The later wars were concerned more with the British desire to impose its control on the Asante to the extent of humiliating them.

It took almost a century, however, from the earliest conflict of 1806-1807 for the colonial power to defeat what was a sophisticated, well organized African state. The Asante empire was a confederacy and possessed many consultative and democratic features (even though its economy was based on slavery). The Ashantehene shared power with others and was ultimately answerable to his subjects for his leadership of the state. This system was replaced by the rule of British colonial and district officers. Throughout this time the Asante were fiercely proud and independent and won the respect of the British. The result of this long history of mutual interaction between Asante and European powers, is that the Asante have the greatest amount of historiography in sub-Saharan Africa. The British regarded the Asante as one of the more civilized African peoples, cataloging their religious, familial and legal systems.[1]

Earlier wars

The British had been involved in three earlier skirmishes:

The Ashanti-Fante War of 1806-1807 began when the Asantehene Osei Bonsu charged some people from Assin with robbing graves. The Fante gave refuge to the accused and a British agent representing the African Company of Merchants sheltered the accused grave robbers in the fort Cape Coast. After a fierce fight the British agent made a treaty with the Asante which included handing over the old, blind Assin king to whom he had given refuge.

The Ga-Fante War of 1811, involved a series of battles between the Asante and their Ga allies against an alliance of the Fante, Akim and Akwapim tribes. The Asante won the main battle but the Akwapim captured a British fort at Tantamkweri and a Dutch fort at Apam.

The Ashanti-Akim-Akwapim War was the expansion of West African Empire of Ashanti against the alliance of Akim and Akwapim tribes from 1814 until 1816. In 1814 the Asante, under the leadership of Asantehene Osei Bonsu, defeated the outnumbered yet brave Akim-Akwapim alliance. However, when they followed up their victory by pillaging the city of Accra, instead of attacking the Europeans, they lost a valuable ally in the Ga people. The coastal people, primarily some of the Fante and the inhabitants of the new town of Accra, who were chiefly Ga, came to rely on British protection against Ashanti incursions. In 1816 the Asante advanced into Fante country, capturing and killing the fleeing Akim-Akwapim warriors and they established themselves as overlords of all the region between the Asante and the sea. Local British, Dutch and Danish authorities were all forced to come to terms with Asante, and in 1817 the African Company of Merchants signed a treaty of friendship that recognized Asante claims to sovereignty over large areas of the coast and its peoples.

First Anglo-Asante War

The First Anglo-Asante War was from 1823 to 1831. Public opinion in Britain had turned against the slave trade and it was abolished in 1807. This crippled the profitability of the African Company of Merchants. In 1821, the company was dissolved and the British government took over the possession of the forts. Largely due to profits from the slave trade, the Asante had risen to be a major force in the area. The Europeans had confined their activities to the coast but from the 1820s the British had begun extending their influence into the interior. They were concerned that the Ashanti were still supplying slaves to the other European nations which had not yet outlawed the slave trade. This led to serious clashes which ultimately became all out war from 1824 to 1831.

In 1823 Sir Charles MacCarthy, rejecting Asante claims to Fante areas of the coast and resisting overtures by the Asante to negotiate, led an invading force from the Cape Coast. The British had allied themselves with the Fante partly because this enabled access to the coast, essential for trade but also because the Asante had good relations with their commercial rivals, the Dutch. The British seriously underestimated the power of the Asante and the extent of their weaponry thanks to years of investment from the slave trade.[2] A British expedition was defeated at the Battle of Nsamankow in 1824. The British were wiped out and MacCarthy was killed. His head and that of Ensign Wetherall were kept as trophies. Major Alexander Gordon Laing, the explorer returned to Britain with news of their fate.

The Asante swept down to the coast inflicting another defeat on the British at Efutu, but disease forced them back. The Asante were so successful in subsequent fighting that in 1826 they again moved on the coast. At first they fought very impressively in an open battle against superior numbers of British allied forces, including Denkyirans. However, the novelty of British Congreve rockets caused the Asante army to withdraw.[3] Concerned at fighting an expensive war against a skillful opponent without any prospect of a payback, the British withdrew to Sierra Leone in 1828 and paid the London Committee of Merchants to maintain the forts. The eased relations with the Asante and in 1831 the Pra River was accepted as the border in a treaty. There followed 30 years of peace.

Second Anglo-Asante War

The Second Anglo-Asante War was from 1863 to 1864. With the exception of a few minor Asante skirmishes across the Pra in 1853 and 1854, the peace between Asanteman and the British had remained unbroken for over 30 years. Then, in 1863, a large Asante delegation crossed the river pursuing a fugitive, Kwesi Gyana. There was fighting, with casualties on both sides, but the governor's request for troops from England was declined and sickness forced the withdrawal of his West Indian troops, with both sides losing more men to sickness than any other factor, and in 1864 the war ended in a stalemate.

Third Anglo-Asante War

The Third Anglo-Asante War lasted from 1873 to 1874. In 1871 Britain purchased the Dutch Gold Coast from the Dutch, including Elmina which was claimed by the Asante. Concerned that they would no longer have access to the sea except through British ports, the Asante invaded the new British protectorate taking European missionaries as hostages.

Colonel Wolseley with 2,500 British troops and several thousand West Indian and African troops (including some Fante) was sent against the Asante. He went to the Gold Coast in 1873, and made plans and preparations before the arrival of his troops in January 1874. He fought the Battle of Amoaful on January 31 of that year, and after five days fighting, concluded with the Battle of Ordahsu. The capital, Kumasi, which was abandoned by the Asante, was briefly occupied by the British and burned. The British were impressed by the size of the palace and the scope of its contents, including "rows of books in many languages"[4] as well as the remains of human sacrifice. The British confiscated much of Kumasi's wealth, including its artistic treasures. Much of the magnificent Asante gold regalia can be seen in London in the British Museum.

The two sides signed the Treaty of Fomena in July 1874, to end the war. It required the Asante to pay an indemnity of 50,000 ounces of gold and give up claims to Elmina and to all payments from the British for the use of forts. They also had to terminate their alliances with several other states, including Denkyera and Akyem. Additionally, they agreed to withdraw their troops from the coast, to keep the trade routes open, and to halt the practice of human sacrifice. Wolseley completed the campaign in two months, and re-embarked his troops for home before the unhealthy season began. Most of the 300 British casualties were from disease.

Some British accounts pay tribute to the hard fighting of the Asante at Amoaful, particularly the tactical insight of their commander: "The great Chief Amanquatia was among the killed. Admirable skill was shown in the position selected by Amanquatia, and the determination and generalship he displayed in the defence fully bore out his great reputation as an able tactician and gallant soldier."[5]

After their success the British withdrew to the coast again. The effect of their defeat of the Asante was to destabilize the entire region. Nearby tribes were no longer intimidated by the mighty Asante and countless wars would rage for years afterwards. French and German encroachments in neighboring areas also helped antagonise the situation. The Ashanti were also able to rebuild their strength and ignore the conditions of the treaty. Only 4000 oz of gold were paid.

This was a modern war, replete with press coverage (including by the renowned reporter Henry Morton Stanley) and printed precise military and medical instructions to the troops. The British government refused appeals to interfere with British armaments manufacturers who sold to both sides.[6]

Fourth Anglo-Asante War

The Fourth Anglo-Asante War was a brief war, from 1894. The Asante turned down an unofficial offer to become a British protectorate in 1891, extending to 1894. Wanting to keep French and German forces out of Asante territory (and its gold), the British were anxious to conquer Asanteman once and for all. The war started on the pretext of failure to pay the fines levied on the Asante monarch by the Treaty of Fomena after the 1874 war.

Sir Francis Scott left Cape Coast with the main expedition force of British and West Indian troops in December 1895, and arrived in Kumasi in January 1896. The Asantehene directed the Asante not to resist. Soon Governor William Maxwell arrived in Kumasi as well. Robert Baden-Powell led a native levy of several local tribes in the campaign. Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh was arrested and deposed. He was forced to sign a treaty of protection and, with other Asante leaders, was sent into exile in the Seychelles.

War of the Golden Stool

In the War of the Golden Stool (1900), the remaining Asante court not exiled to the Seychelles mounted an offensive against the British Resident at the Kumasi Fort, but were defeated. Yaa Asantewaa (1840-1921), the Queen-Mother of Ejisu and other Asante leaders were also sent to the Seychelles. The revolt was provoked by the demand of the Governor of the Gold Coast, Sir Frederick Hodgson, to sit on the Golden Stool. The Asante believed that soul of the nation resided in this stool and no one, not even the king, was allowed to sit on it. Hodgson was ignorant of the sacredness of the stool, but he also wanted to humiliate the Asante. A British captain who had previously been commissioned to find the location of the Golden Stool and beat women and children to compel them to reveal its whereabouts - they didn't co-operate. The Asante remained silent after Hodgson's speech and when the assembly ended, they went home and prepared for war. Although they were finally conquered by the British, the Asante claimed victory because they fought only to preserve the Golden Stool.[7]

The role played by Yaa Asantewaa has been debated; was her leadership symbolic, or was she the principal leader of the revolt, which for "three months laid siege to the British mission at the fort of Kumasia" before the British brought in reinforcements? After breaking the siege, the "the British troops plundered the villages, killed much of the population, confiscated their lands and left the remaining population dependent upon the British for survival."[8] The Ashanti territories became part of the Gold Coast colony on January 1, 1902.

Although mainly ceremonial, the office of Asantehene did continue, after a lapse during Premeh's exile. He was allowed to return to the Gold Coast in 1926. The British did not let him use the title of Asantehene (he was permitted to use the subordinate title, Kumasehene, ruler of Kumasi) but in 1935, the title was revived. As an ancient office of clan leadership, the title is recognized by the Constitution of Ghana. In 1999, King Otumfuo Osei Tutu II became the 16th Asantehene, King of the Asante. He is a direct descendant of Otumfuo Osei Tutu I.

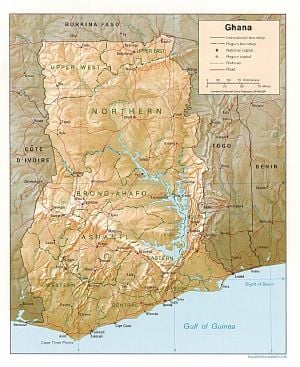

The British consolidated their possessions and incorporated the Asante empire to create the Gold Coast which after independence became Ghana. Like many other African countries it is an artificial construction of an imperial power. One of the main reasons for its internal instability is the many internal tensions between its different constituent tribes put together for the convenience of its imperial ruler.

See also

- Asante Union

- British Empire

- Ghana

Notes

- ↑ R.S. Rattray. "Ashanti Law and Constitution" (Oxford University Press, 1929) ASIN B0007JF5WC

- ↑ http://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/goldcoast.htm Retrieved September 14, 2008

- ↑ Alan Lloyd. "The drums of Kumasi: the story of the Ashanti wars". (London, UK: Longmans), p. 39-53

- ↑ Alan Lloyd. "The drums of Kumasi: the story of the Ashanti wars". (London, UK: Longmans), p. 172-174, 175

- ↑ Charles Rathbone Low, A Memoir of Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet J. Wolseley, R. Bentley: 1878, pp. 57-176

- ↑ Alan Lloyd. "The drums of Kumasi: the story of the Ashanti wars". (London, UK: Longmans), p. 83

- ↑ History of golden Stool. Ghana Web. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ↑ (Danuta Bois, 1998, Yaa Asantewaa. Distinguished Women of Past and Present. Retrieved May 24, 2008. See Boahen, A. Adu on whether her leadership was military or symbolic.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agbodeka, Francis. 1971. African Politics and British Policy in the Gold Coast, 1868–1900: A Study in the Forms and Force of Protest. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810103680.

- Agyeman-Duah, Ivor, and Abdulai Awudu. 2001. Yaa Asantewaa the exile of King Prempeh and the heroism of an African queen. GH: Centre for Intellectual Renewal. ISBN 9789988812034.

- Akyeampong, E., Prempeh, Agyeman Prempeh, et al. 2008. The History of Ashanti Kings and the Whole Country Itself' and Other Writings, by Otumfuo, Nana Agyeman Prempeh I. Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 9780197264157

- Boahen, A. Adu. 2000. "Yaa Asantewaa in the Yaa Asantewa War of 1900: military leader or symbolic head?" Ghana Studies. 3:111-135.

- Edgerton, Robert B. 1995. The fall of the Asante Empire: the hundred-year war for Africa's Gold Coast. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 9780029089262.

- Lloyd, Alan. 1964. The drums of Kumasi: the story of the Ashanti wars. London, UK: Longmans.

- McCarthy, Mary. 1983. Social Change and the Growth of British Power in the Gold Coast: The Fante States, 1807–1874. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 0819131482.

- Rattray, R.S. Ashanti Law and Constitution. Oxford University Press, 1929. ASIN B0007JF5WC

- Wilks, Ivor. 1975. Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521204631.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.