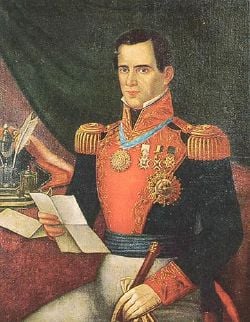

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (February 21, 1794 – June 21, 1876), also known simply as Santa Anna, was a Mexican political leader who greatly influenced early Mexican and Spanish politics and government, first fighting against independence from Spain, and then becoming its chief general and president at various times over a turbulent 40-year career. He was President of Mexico eleven non-consecutive times over a period of 22 years. Unfortunately, he started a tradition of one man dominating the political scene that men such as Porfirio Díaz and others would continue, and of dictatorial rule, that disadvantaged the development of genuine participatory democracy in Mexico.

He played a critical role in gaining political independence for Mexico. However, rule from Spain was replaced by rule by an wealthy elite while the majority of Mexicans, and especially indigenous people, owned a tiny percentage of the land. He was more interested in his self-image than in the welfare of his people. There does not appear to have been a shared vision about how the independent nation would structure itself, or what its social vision would be. Independence in and of itself has often been coveted with the expectation that once achieved, life will automatically become better and problems—of which the colonial oppressors were the cause—would resolve themselves. The Mexican experience suggests the importance of a shared social vision, and of promoting debate and discussion about this if any state is to cohere into a truly cooperative venture that seeks to work for the common good, not only for the benefit of an elite few.

Early years

Santa Anna was born in Xalapa, Veracruz, on February 21, 1794, the son of Antonio López de Santa Anna and Manuela Pérez de Lebrón. His family belonged to the criollo middle class, and his father served at one time as a subdelegate for the Spanish province of Veracruz. After a limited schooling, the young Santa Anna worked for a merchant of Veracruz. In June 1810, he was appointed a cadet in the Fijo de Vera Cruz infantry regiment under the command of José Joaquín de Arredondo. Santa Anna spent the next years battling insurgents and policing the Indian tribes of the internal provinces (political divisions of Mexico). Like most criollo officers in the Royalist army, he remained loyal to Spain for a number of years and fought against the movement for Mexican independence.

Personal life

Santa Anna married Inés García and fathered five children. She died in 1844. After a month of mourning, the 50 year old Santa Anna married 15 year old María Dolores de Tosta and fathered several more children by her. Santa Anna is rumored to have wed the very young Melchora Barrera during his occupation of San Antonio de Béjar in 1836. He sent her back to Mexico City, where he provided for her and their child.

Military career

In 1810, the same year that Mexico declared its independence from Spain, the sixteen-year-old joined the colonial Spanish Army under commanding officer José Joaquín de Arredondo, who taught him much about dealing with Mexican nationalist rebels. In 1811, Santa Anna was wounded in the arm by a Chichimec arrow while on a campaign against northern Indian tribes. In 1813, he served in Texas against the Gutiérrez/Magee Expedition, and at the Battle of Medina he was cited for bravery. In the aftermath of the rebellion the young officer witnessed Arredondo's fierce counter-insurgency policy of mass executions, and historians have speculated that Santa Anna modeled his policy and conduct in the Texas Revolution on his experience under Arredondo.

During the next few years, in which the war for independence reached a stalemate, Santa Anna erected villages for displaced citizens near Veracruz. He also pursued gambling, a vice that would follow him all through his life.

In 1821, Santa Anna switched sides and declared his loyalty to insurgent leader "El Libertador:" The future Emperor of Mexico, Agustín de Iturbide. He rose to prominence by quickly driving the Spanish forces out of the vital port city of Veracruz in 1821.[1] After Santa Anna declared his loyalty to the Emperor, Iturbide rewarded him with the rank of general, yet in 1823, Santa Anna was among the military leaders supporting the Plan de Casa Mata to overthrow Iturbide and declare Mexico a Republic. Later, Santa Anna would play important roles in replacing presidents Manuel Gómez Pedraza and Vicente Guerrero. By 1824, Santa Anna was appointed governor of the state of Yucatán. On his own initiative, Santa Anna prepared to invade Cuba, which remained under Spanish rule, but he possessed neither the funds nor sufficient support for such an adventure.

In 1829, Spain made its final attempt to retake Mexico in Tampico with an invading force of 2,600 soldiers. Santa Anna marched against the Barradas Expedition with a much smaller force and defeated the Spaniards, many of whom were suffering from yellow fever. Santa Anna was declared a hero, which he relished, and from then on, he styled himself "The Victor of Tampico" and "The Savior of the Motherland."

Politics

Santa Anna declared himself retired, "unless my country needs me." He decided he was needed when Anastasio Bustamante led a coup, overthrowing and killing President Vicente Guerrero. Santa Anna was elected president in 1833. At first, he had little interest in actually running the country, giving a free hand to his vice-president Valentín Gómez Farías, a liberal reformer.

Gómez Farías worked hard to root out corruption, which stepped on some powerful toes among the military, wealthy landowners, and the Catholic Church. When these voiced their displeasure, Santa Anna dismissed Farías, declared the Constitution suspended, disbanded the Congress, and worked to concentrate power in the central government. This was applauded by some conservatives, but met with considerable disapproval from other sectors.

Several states went into open rebellion: Present-day Texas (which was part of the state of Coahuila and Texas), San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Durango, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Yucatán, Jalisco and Zacatecas. Of these states, only the Texas portion of the state of Coahuila and Texas voted to formally separate from the Mexican confederation. The other states expressed a desire to return to the 1824 constitution, not to form their own countries.

The Zacatecan militia, the largest and best supplied of the Mexican states, led by Francisco Garcia, was well armed with .753 caliber British "Brown Bess" muskets and Baker .61 rifles. After two hours of combat, on May 12, 1835, the "Army of Operations" defeated the Zacatecan militia and took almost 3,000 prisoners. Santa Anna allowed his army to ransack the city for forty-eight hours. He planned to put down the rebellion first in Zacatecas before moving on to Coahuila y Tejas.

By this time, Santa Anna had relinquished the presidency four times. When the drums of war beat, he appointed a successor, and went off into battle. However, as he marched north into Texas, it was acknowledged that Santa Anna was indeed the ruler of Mexico.

Texas

Like other states discontented with the central Mexican authority, the Texas department of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas went into rebellion in late 1835, and declared itself independent on March 2, 1836. (part of the Texas Revolution and Republic of Texas.) Santa Anna marched north to bring Texas back under Mexican control. Santa Anna's forces killed 187-250 Texan defenders at the Battle of the Alamo (February 23-March 6, 1836) and executed 342 Texan prisoners at the Goliad massacre (March 27, 1836).

Santa Anna was soundly defeated a few weeks after the Goliad massacre by Sam Houston's soldiers at the Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836), with the Texan army shouting "Remember Goliad, Remember the Alamo!" A small band of Texas forces captured Santa Anna the day after the battle, on April 22.

Acting Texas president David G. Burnet and Santa Anna signed the Treaties of Velasco "in his official character as chief of the Mexican nation, he acknowledged the full, entire, and perfect Independence of the Republic of Texas." In exchange, Burnet and the Texas government guaranteed Santa Anna's life and transport to Veracruz. Before Santa Anna could leave Texas, 200 angry volunteer soldiers from the United States threatened to remove him from his boat and kill him as it was leaving the port of Velasco. Back in Mexico City, a new government declared that Santa Anna was no longer president and the treaty was thus null and void.

While captive in Texas, Joel Roberts Poinsett—U.S. minister to Mexico in 1824—offered a harsh assessment of General Santa Anna's situation, stating: "Say to General Santa Anna that when I remember how ardent an advocate he was of liberty ten years ago, I have no sympathy for him now, that he has gotten what he deserves."

To this message, Santa Anna made the reply:

Say to Mr. Poinsett that it is very true that I threw up my cap for liberty with great ardor, and perfect sincerity, but very soon found the folly of it. A hundred years to come my people will not be fit for liberty. They do not know what it is, unenlightened as they are, and under the influence of a Catholic clergy, a despotism is the proper government for them, but there is no reason why it should not be a wise and virtuous one.[2]

Redemption, dictatorship, and exile

After some time in exile in the United States, and after meeting with U.S. president Andrew Jackson in 1837, he was allowed to return to Mexico aboard the USS Pioneer to retire to his magnificent hacienda in Veracruz, called Manga de Clavo.

In 1838, Santa Anna discovered a chance to redeem himself from his Texas losses, when French forces landed in Veracruz, Mexico in the Pastry War, a short conflict which began after Mexico rejected French demands for financial recompense for losses suffered by some French citizens. The Mexican government gave Santa Anna control of the army and ordered him to defend the nation by any means necessary. He engaged the French at Veracruz and, as the Mexican resistance retreated after a failed assault, Santa Anna was hit in the leg and hand by cannon fire. His ankle was shattered and this resulted in the amputation of his leg, which he ordered buried with full military honors. (Santa Anna famously used a cork leg after the amputation, but it was captured and kept by American troops during the Mexican-American War.) Despite Mexico's capitulation to French demands, Santa Anna was able to use his wound to re-enter Mexican politics as a hero.

Soon after, Santa Anna was once again asked to take control of the provisional government as Anastasio Bustamante's presidency turned chaotic. Santa Anna accepted and became president for the fifth time. Santa Anna took over a nation with an empty treasury. The war with France had weakened Mexico, and the people were discontented. Also, a rebel army led by Generals Jose Urrea and José Antonio Mexía was marching towards the Capital, at war against Santa Anna. The rebellion was crushed in Puebla, by an army commanded by the president himself.

Santa Anna's rule was even more dictatorial than his first administration. Anti-Santanista newspapers were banned and dissidents jailed. In 1842, a military expedition into Texas was renewed, with no gain but to further persuade the Texans of the benefits of American annexation.

His demands for ever greater taxes aroused ire, and several Mexican states simply stopped dealing with the central government, Yucatán and Laredo going so far as to declare themselves independent republics. With resentment ever growing against the president, Santa Anna once again stepped down from power. Fearing for his life, Santa Anna tried to elude capture, but in January 1845, he was apprehended by a group of Indians near Xico, Veracruz, turned over to authorities, and imprisoned. His life was spared, but the dictator was exiled to Cuba.

Mexican-American War

In 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. Santa Anna wrote to Mexico City saying he no longer had aspirations to the presidency, but would eagerly use his military experience to fight off the foreign invasion of Mexico as he had in the past. President Valentín Gómez Farías was desperate enough to accept the offer and allowed Santa Anna to return. Meanwhile, Santa Anna had secretly been dealing with representatives of the United States, pledging that if he were allowed back in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades, he would work to sell all contested territory to the United States at a reasonable price. Once back in Mexico at the head of an army, Santa Anna reneged on both of these agreements. Santa Anna declared himself president again and unsuccessfully tried to fight off the United States invasion. (However, his actions did inspire the Sea chanty, "Santianna.")

In 1851, Santa Anna went into exile in Kingston, Jamaica, and two years later, moved to Turbaco, Colombia. In April 1853, he was invited back by rebellious conservatives, with whom he succeeded in retaking the government. This reign was no better than his earlier ones. He funneled government funds to his own pockets, sold more territory to the United States (the Gadsden Purchase), and declared himself dictator for life with the title "Most Serene Highness." The Ayutla Rebellion of 1854 once again removed Santa Anna from power.

Despite his generous payoffs to the military for loyalty, by 1855, even his conservative allies had had enough of Santa Anna. That year a group of liberals led by Benito Juárez and Ignacio Comonfort overthrew Santa Anna, and he fled back to Cuba. As the extent of his corruption became known, he was tried in absentia for treason and all his estates confiscated. He then lived in exile in Cuba, the United States, Colombia, and St. Thomas. During his time in New York City, he is credited as bringing the first shipments of chicle, the base of chewing gum, to the United States, but he failed to profit from this, since his plan was to use the chicle to replace rubber in carriage tires, which was tried without success. The American assigned to aid Santa Anna while he was in the United States, Thomas Adams, conducted experiments with the chicle and called it "Chiclets," which helped found the chewing gum industry. Santa Anna was a passionate fan of the sport of cockfighting. He would invite breeders from all over the world for matches and is known to have spent tens of thousands of dollars on prize roosters.

In 1874, he took advantage of a general amnesty and returned to Mexico. Santa Anna died in Mexico City two years later, on June 21, 1876, penniless and heartbroken. Crippled and almost blind from cataracts, he was ignored by the Mexican government when the anniversary of the Battle of Churubusco occurred.

Presidencies

Santa Anna held the office 11 times:

- May 16, 1833-June 3, 1833

- June 18, 1833-July 5, 1833

- October 27, 1833-December 15, 1833

- April 24, 1834-January 27, 1835

- March 20, 1839-July 10, 1839

- October 10, 1841-October 26, 1842

- March 4, 1843-October 4, 1843

- June 4, 1844-September 12, 1844

- March 21, 1847-April 2, 1847

- May 20, 1847-September 15, 1847

- April 20, 1853-August 9, 1855

In popular culture

Santa Anna is mentioned several times in the movie, The Mask of Zorro. He appears in a scene that was deleted from the theatrical release, portrayed by Joaquim de Almeida.

Santa Anna was one of the main characters in the 2004 movie, The Alamo, portrayed by Emilio Echevarría.

Santa Anna was also mentioned in a King of the Hill episode called "The Last Shinsult," in which Hank Hill's father Cotton Hill steals the wooden leg of Santa Anna as it makes its way back to Mexico in exchange for a driver's license.

Legacy

Santa Anna was a devoted collector of Napoleonic artifacts, and also considered himself the "Napoleon of the West." His nickname, though, was "The Eagle." While it is understood that Santa Anna considered himself "Napoleon of the West," he did so only after the Texas Telegraph and Register referred to him as such. He took great pride in what he saw as his image as a soldier, and developed a persona of a statesman and general of great stature.

Legend has it that his lack of preparations or even defensive measures prior to the Battle of San Jacinto were due to his being entertained by Emily Morgan, a mulatto girl, in his tent. It gave rise to the song "The Yellow Rose of Texas." There is however, no historical proof that his meeting with Emily Morgan ever occurred.

In 1897, Santa Anna's grandson by his second marriage, Santa Anna III (1881–1965), entered the Jesuit order.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Fred, and Andrew Cayton. The Dominion of War: Empire and Liberty in North America: 1500-2000. New York: Penguin, 2005. ISBN 0143036513

- Borroel, Roger. The Texas Revolution of 1836: A Concise Historical Perspective Based on Original Sources. San Antonio: La Villita Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-928792-09-X

- Caruso, John Anthony. The Liberators of Mexico. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1967.

- Jackson, Jack and John Wheat. Almonte's Texas: Juan N. Almonte's 1834 Inspection, Secret Report, & Role in the 1836 Campaign. Austin: Texas State Historical Assoc., 2003. ISBN 0876112076

- Roberts, Randy and James S. Olson. A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory. New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0743212339

- Santa Anna, Antonio and Ann F. Crawford. The Eagle: The Autobiography of Santa Anna. Abilene, Texas: State House Press. ISBN 0938349295

- Santoni, Pedro. Mexicans at Arms: Puro Federalist and the Politics of War, 1845-1848. Fort Worth: TCU Press, 1996. ISBN 0875651585

- Villalpando César, José Manuel. Las balas del invasor: La expansion territorial de los Estados Unidos a costa de Mexico. Miguel Angel Porruas. ISBN 9688427357

- Wharton, Clarence Ray. El Presidente: A Scetch of the Life of Santa Anna. Austin TX: Gammel's Book Store, 1926.

External links

All links retrieved August 11, 2023.

- Santa Anna Letters Portal to Texas History.

- Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna The Handbook of Texas Online.

- Sketch of Santa Anna from A pictorial history of Texas, from the earliest visits of European adventurers, to A.D. 1879.

| Preceded by: Valentín Gómez Farías |

President of Mexico 1833–1835 |

Succeeded by: Miguel Barragán |

| Preceded by: Anastasio Bustamante |

Acting President of Mexico 1839 |

Succeeded by: Nicolás Bravo |

| Preceded by: Francisco Javier Echeverría |

Acting President of Mexico 1841–1842 |

Succeeded by: Nicolás Bravo |

| Preceded by: Nicolás Bravo |

Acting President of Mexico 1843 |

Succeeded by: Valentín Canalizo |

| Preceded by: Valentín Canalizo |

Acting President of Mexico 1844 |

Succeeded by: Valentín Canalizo |

| Preceded by: Valentín Gómez Farías |

Acting President of Mexico 1847 |

Succeeded by: Pedro María Anaya |

| Preceded by: Manuel María Lombardini |

Acting President of Mexico 1853–1855 |

Succeeded by: Martín Carrera |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.