Asana

Asana (Sanskrit: meaning "sitting down") refers to body positions that are prescribed in the practice of Yoga to cultivate physical discipline, improve the body's flexibility, and enable the practitioner to remain seated in meditation for extended periods. In Yoga terminology, asana denotes two things: the place where a practitioner sits and the manner (posture) in which he or she sits. In the authoritative Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, asana is described as being "seated in a position that is firm, but relaxed" (Ch. 2: 46). As the repertoire of postures has expanded and moved beyond the simple sitting posture over the centuries, modern usage has come to include variations from lying on the back and standing on the head, to a variety of other positions. In the Yoga sutras, Patanjali mentions the execution of an asana as the third of the eight limbs of Classical or Raja yoga (Ch. 2: 29).

The word asana in Sanskrit does appear in many contexts denoting a static physical position, although, as noted, traditional usage is specific to the practice of yoga. Traditional usage defines asana as both singular and plural. In English, plural for asana is defined as asanas. In addition, English usage within the context of yoga practice sometimes specifies yogasana or yoga asana, particularly with regard to the system of the Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga.

Practice

Asana refers to various body postures that are practiced for disciplining the senses. This Sanskrit term literally means "seat," and originally referred mainly to seated positions. With the rise of Hatha yoga, it came to be used for yoga "postures" as well. According to Indian tradition, the highest form of yoga is known as Raja Yoga (Sanskrit: "Royal yoga"), also called "Ashtanga Yoga" ("Eight-Limbed Yoga"), and it is held to be authoritative by all schools of yoga. Raja Yoga aims at controlling all thought-waves or mental modifications. It is called the "King of the Yogas" because it is primarily concerned with the mind, which is traditionally conceived as the "king" of the psycho-physical structure that does its bidding. Because of the relationship between the mind and the body, the body must be first "tamed" through self-discipline and purified by various means. A good level of overall health and psychological integration must be attained before the deeper aspects of yoga can be pursued. Humans have all sorts of addictions and obsessions and these preclude the attainment of tranquil abiding (meditation). Through restraint (yama) such as celibacy, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and careful attention to one's actions of body, speech and mind, the human being becomes fit to practice meditation. This yoke that one puts upon oneself (discipline) is another meaning of the word yoga.

Patanjali's famous Yoga Sutra describes asana as the third of the eight limbs of classical, or Raja Yoga. Among these practices, asanas are the physical movements of yoga practice and, in combination with pranayama or breathing techniques constitute the style of yoga referred to as Hatha Yoga. Patanjali describes asana as a "firm, comfortable posture," referring specifically to the seated posture, most basic of all the asanas. He further suggests that meditation is the path to samadhi (transpersonal self-realization). They are part of a larger system called Raja/Ashtanga Yoga, whose eight limbs are summarized as follows:

- Yama - Code of conduct - self-restraint

- Niyama - religious observances - commitments to practice, such as study and devotion

- Asana - integration of mind and body through physical activity

- Pranayama - regulation of breath leading to integration of mind and body

- Pratyahara - abstraction of the senses, withdrawal of the senses of perception from their objects

- Dharana - concentration, one-pointedness of mind

- Dhyana - meditation (quiet activity that leads to samadhi)

- Samadhi - the quiet state of blissful awareness, superconscious state.

In the West, the asanas (physical aspect of yoga) has been much popularized, and devoted celebrity practitioners like Madonna and Sting have contributed to the increased visibility of the practice. However, the emphasis on physical positions has given rise to the perception that yoga consists only of asana practice, which is traditionally incorrect. A more spiritual purpose is to quiet the mind, to understand one's true nature, and to facilitate the flow of prana to aid in balancing the koshas (sheaths) of the physical and metaphysical body. Depending on the level of mastery, the practitioner of asanas is supposed to achieve many supernatural abilities. For instance, a yogi who has mastered Mayurasana is said not to be affected by eating any poison. Nevertheless, the practice of asanas is allegedly associated with health benefits such as the following:

- improving muscle flexibility

- improving tendon strength

- improving stamina

- improving the respiratory system

- helping to control blood pressure

- reducing stress.

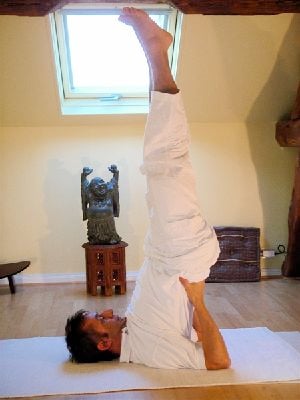

Variety of asanas

In his The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga (1959), Swami Vishnu-devananda published a compilation of 66 basic postures and 136 variations of those postures. Sri Dharma Mittra suggested that there are an infinite number of asanas and in 1975, he set out to catalogue the vast number in the Master Yoga Chart of 908 Postures, as an offering of devotion to his guru, Swami Kailashananda Maharaj. Through this effort, he compiled 1300 variations, derived from gurus, and yogis, as well as both ancient and contemporary texts.[1] Although it is impossible to establish a complete and exact set of yoga postures, this work is considered a leading collection by students and yogis alike.[2][3]

In the Yoga Sutra, Patanjali suggests that the only requirement for practicing asanas is that it be "steady and comfortable".[4] The body is held poised, and relaxed, with the practitioner experiencing no discomfort.

When control of the body is mastered, practitioners free themselves from the duality of heat/cold, hunger/satiety, joy/grief, which is the first step toward the unattachment that relieves suffering.[5] This non-dualistic perspective comes from the Sankya school of the Himalayan Masters.[6]

Listed below are traditional practices for performing asana:

- The stomach should be relatively empty.

- Force or pressure should not be used, and the body should not tremble.

- Lower the head and other parts of the body slowly; in particular, raised heels should be lowered slowly.

- The breathing should be controlled. The benefits of asanas increase if the specific pranayama to the yoga type is performed.

- If the body is stressed, perform Corpse Pose or Child Pose

- Some claim that asanas, especially inverted poses, are to be avoided during menstruation.[7] Others deny this view.

- Asanas are generally not performed on floor, but on Yoga mats instead.

One of the common practices in yoga is the Surya Namaskara, or the Sun Salutation, is a form of worshiping Surya, the Hindu solar deity by concentrating on the Sun, for vitalization. The physical aspect of the practice links together twelve asanas in a dynamically expressed series. A full round of Surya namaskara is considered to be two sets of the twelve poses, with a change in the second set where the opposing leg is moved first. The asanas included in the sun salutation differ from tradition to tradition.

Some common asanas

Notes

- ↑ Dharma Mittra, Asanas: 608 Yoga Poses (New World Library, 2003, ISBN 1-57731-402-6).

- ↑ Yoga.com Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ↑ Yoga Journal, Talking Shop with Dharma Mittra. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ↑ Patanjali (± 300-200 B.C.E.) Yoga sutras, Book II:29

- ↑ Georg Feuerstein, The Deeper Dimensions of Yoga: Theory and Practice (Shambhala Publications, Massachusetts, 2003).

- ↑ Swami Rama, Living with the Himalayan Masters (Himalayan Institute Press, Pennsylvania; India, 1980).

- ↑ Effect of Inverted Yoga Postures on Menstruation & Pregnancy Retrieved November 16, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dasgupta, Surendranath. 1973. A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol. I. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120804120

- Patañjali, and B.S. Miller. 1996. Yoga discipline of freedom: the Yoga Sutra attributed to Patanjali; a translation of the text, with commentary, introduction, and glossary of keywords. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press. ISBN 0520201906

- Patanjali, and B. K. S. Iyengar. 2002. Light on the yoga sutras of Patanjali. London: Thorsons. ISBN 0007145160

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli, and Charles A. Moore (eds.). A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973. ISBN 0691019584

- Sharma, Chandrahar. 2003. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120803647

- Sivananda, Swami. Raja Yoga, reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1425359829

- Thakar, Vimala. Glimpses of Raja Yoga: An Introduction to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras (Yoga Wisdom Classics). Rodmell Press; 1st North American Pbk. Ed edition, 2004. ISBN 978-1930485075

- Villoldo, Alberto. 2007. Yoga, power, and spirit Patanjali the Shaman. Carlsbad, Calif: Hay House, Inc. ISBN 9781401910471

- Vivekananda, Swami. Raja-Yoga. Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center; Pocket Rev edition (June 1980). ISBN 978-0911206234

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Asana history

- Raja_Yoga history

- Yoga history

- History_of_Yoga history

- Buddhism_and_Hinduism history

- Patanjali history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.