| |

| Born | September 23, 63 B.C.E., Rome |

| Accession | January 16, 27 B.C.E. |

| Died | August 19, 14 C.E., Nola |

| Predecessor | none (heir to Julius Caesar) |

| Successor | Tiberius, stepson by 3rd wife and adoptive son |

| Spouse(s) | 1) Clodia Pulchra d 40 B.C.E. 2) Scribonia 40 B.C.E. – 38 B.C.E. 3) Livia Drusilla 38 B.C.E. to 14 C.E. |

| Issue | Julia the Elder |

| Father | Gaius Octavius |

| Mother | Atia Balba Caesonia |

| Dynasty | Julio-Claudian |

Augustus (Latin: IMPERATOR CAESAR DIVI FILIVS AVGVSTVS) (September 23, 63 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.), known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (in English, Octavian), for the period of his life prior to 27 B.C.E., was the first and among the most important of the Roman Emperors.

Although he preserved the outward form of the Roman Republic, he ruled as an autocrat for more than 40 years and his rule is the dividing line between the Republic and the Roman Empire. He ended a century of civil wars and gave Rome an era of peace, prosperity, and imperial greatness, known as the Pax Romana, "Roman peace." Over the next four-hundred years, Rome would establish municipalities across Western Europe and North Africa, build roads, public buildings, and construct the infrastructure of governance that still provides the basis of modern political systems. Augustus was concerned with public morality, and enacted legislation. He was a great believer in what he thought of as "republican values," such as hard work, discipline, obedience, piety, and the appreciation of art and culture. He encouraged marriage, giving tax concessions to couples with children, made adultery a crime, and he also restricted luxury and extravagance. He believed that peace depended on citizens faithfully performing their religious duties. He became head of the state cult (pontifex maximus) as well as temporal ruler. He increased the length of tenure of provincial governors because this proved to provide more stability. Throughout Europe, many different people gained a sense of belonging to the same world, governed by the same moral code and Roman law. This sense of a common European home continued to inform European thought even in the Dark Ages and still contributes to European identity today. When the founders of the United States decided to establish the office of President, they spoke of inaugurating an "Augustan Age." This refers both to the Augustan peace and to the high cultural achievement of his era, when many poems and texts on such themes as patriotism, the world of nature, and history were dedicated to him.

During his reign, Virgil's Aeneid was completed, as were Horace's Odes (Books I-III), among other classical works of significance.

Early life

He was born in Rome (or Velletri) on September 23, 63 B.C.E., with the name Gaius Octavius. His father, also Gaius Octavius, came from a respectable but undistinguished family of the equestrian order and was governor of Macedonia. Shortly after Octavius's birth, his father gave him the surname of Thurinus, possibly to commemorate the Macedonian victory at Thurii over a rebellious band of slaves. His mother, Atia, was the niece of Gaius Julius Caesar, soon to be Rome's most successful general and Dictator. He spent his early years in his grandfather's house near Veletrae (modern Velletri). In 58 B.C.E., when he was four years old, his father died. He spent most of his remaining childhood in the house of his stepfather, Lucius Marcius Philippus.

In 51 B.C.E., when he was eleven years old, Octavius delivered the funeral oration for his grandmother, Julia Caesaris (sister of Julius Caesar), elder sister of Caesar. He put on the toga virilis at fifteen, and was elected to the College of Pontiffs. Caesar requested that Octavius join his staff for his campaign in Africa, but his mother protested that he was too young. The following year (46 B.C.E.), she consented for him to join Caesar in Hispania, but he fell ill and was unable to travel. When he had recovered, he sailed to the front, but was shipwrecked. After coming ashore with a handful of companions, he made it across hostile territory to Caesar's camp, which impressed his great-uncle considerably. Caesar and Octavius returned home in the same carriage, and Caesar secretly changed his will.

Rise to power

When Julius Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March (the 15th) 44 B.C.E., Octavius was studying in Apollonia, Illyria. When Caesar's will was read it revealed that, having no legitimate children, he had adopted his great-nephew as his son and main heir. By virtue of his adoption, Octavius assumed the name Gaius Julius Caesar. Roman tradition dictated that he also append the surname Octavianus (Octavian) to indicate his biological family; however, no evidence exists that he ever used that name. Mark Antony later charged that he had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favors, though Lives of the Twelve Caesars scribe, Suetonius, describes Antony's accusation as political slander.[1]

Octavian recruited a small force in Apollonia. Crossing over to Italia, he bolstered his personal forces with Caesar's veteran legionaries, gathering support by emphasizing his status as heir to Caesar. Only eighteen years old, he was consistently underestimated by his rivals for power.

In Rome, he found Mark Antony and the Optimates led by Marcus Tullius Cicero in an uneasy truce. After a tense standoff, and a war in Cisalpine Gaul after Antony tried to take control of the province from Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, he formed an alliance with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus {a triumvir), Caesar's principal colleagues. The three formed junta called the Second Triumvirate, an explicit grant of special powers lasting five years and supported by law, unlike the unofficial First Triumvirate of Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, Caesar, and Marcus Licinius Crassus.[2]

The triumvirs then set in motion proscriptions in which 300 senators and 2,000 of the Equestrian order or equites were deprived of their property and, for those who failed to escape, their lives. Going beyond a simple purge of those allied with the assassins, the triumvirs were probably motivated by a need to raise money to pay their troops.[3]

Antony and Octavian then marched against Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius, who had fled to the east. After two battles at Philippi in Macedonia, the Caesarian army was victorious and Brutus and Cassius committed suicide (42 B.C.E.). After the battle, a new arrangement was made between the members of the Second Triumvirate: While Octavian returned to Rome, Antony went to Egypt where he allied himself with Cleopatra VII, the former lover of Julius Caesar and mother of Caesar's infant son, Caesarion. Lepidus, now clearly marked as an unequal partner, settled for the province of Africa.

While in Egypt, Antony had an affair with Cleopatra that resulted in the birth of three children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene (II), and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Antony later left Cleopatra to make a strategic marriage with Octavian's sister, Octavia Minor, in 40 B.C.E. During their marriage Octavia gave birth to two daughters, both named Antonia. In 37 B.C.E., Antony deserted Octavia and went back to Egypt and Cleopatra. The Roman dominions were then divided between Octavian in the West and Antony in the East.

Antony occupied himself with military campaigns in the East and a romantic affair with Cleopatra; Octavian built a network of allies in Rome, consolidated his power, and spread propaganda implying that Antony was becoming less than Roman because of his preoccupation with Egyptian affairs and traditions. The situation grew more and more tense, and finally, in 32 B.C.E., the senate officially declared war on "the Foreign Queen," to avoid the stigma of yet another civil war. It was quickly decided. In the bay of Actium on the western coast of Greece, after Antony's men began deserting, the fleets met in a great battle in which many ships burned and thousands on both sides lost their lives. Octavian defeated his rivals, who then fled to Egypt. He pursued them, and following another defeat, Antony committed suicide. Cleopatra also committed suicide after her upcoming role in Octavian's Triumph was "carefully explained to her," and Caesarion was "butchered without compunction." Octavian supposedly said "two Caesars are one too many" as he ordered Caesarion's death.[4]

Octavian becomes Augustus: The creation of the Principate

The Western half of the Roman Republic territory had sworn allegiance to Octavian prior to Actium in 31 B.C.E., and after Actium and the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, the Eastern half followed suit, placing Octavian in the position of ruler of the Republic. Years of civil war had left Rome in a state of near-lawlessness, but the Republic was not prepared to accept the control of Octavian as a despot. At the same time, Octavian could not simply give up his authority without risking further civil wars amongst the Roman generals, and even if he desired no position of authority whatsoever, his position demanded that he look to the well-being of the city and provinces. Disbanding his personal forces, Octavian held elections and took up the position of consul; as such, though he had given up his personal armies, he was now legally in command of the legions of Rome.

The first settlement

In 27 B.C.E., Octavian officially returned power to the Roman Senate, and offered to relinquish his own military supremacy over Aegyptus.

Reportedly, the suggestion of Octavian's stepping down as consul led to rioting amongst the Plebeians in Rome. A compromise was reached between the Senate and Octavian's supporters, known as the First Settlement. Octavian was given proconsular authority over the Western half and Syria. The provinces combined contained almost 70 percent of the Roman legions.

The Senate also gave him the titles Augustus and Princeps. Augustus was a title of religious rather than political authority. In the mindset of contemporary religious beliefs, it would have cleverly symbolized a stamp of authority over humanity that went beyond any constitutional definition of his status. Additionally, after the harsh methods employed in consolidating his control, the change in name would also serve to separate his benign reign as Augustus from his reign of terror as Octavian. Princeps translates to "first-citizen" or "first-leader." It had been a title under the Republic for those who had served the state well. For example, Pompey had held the title.

In addition, and perhaps the most dangerous innovation, the Roman Senate granted Augustus the right to wear the Civic Crown of laurel and oak. This crown was usually held above the head of a Roman general during a Roman Triumph, with the individual holding the crown charged to continually repeat, "Remember, thou art mortal," to the triumphant general. The fact that not only was Augustus awarded this crown but awarded the right to actually wear it upon his head is perhaps the clearest indication of the creation of a monarchy. However, it must be noted that none of these titles, or the Civic Crown, granted Octavian any additional powers or authority. For all intents and purposes the new Augustus was simply a highly-honored Roman citizen, holding the consulship.

These actions were highly abnormal from the Roman Senate, but this was not the same body of patricians that had murdered Caesar. Both Antony and Octavian had purged the Senate of suspect elements and planted it with their loyal partisans. How free a hand the Senate had in these transactions, and what back room deals were made, remain unknown.

The second settlement

In 23 B.C.E., Augustus renounced the consulship, but retained his consular imperium, leading to a second compromise between Augustus and the Senate, known as the Second Settlement. Augustus was granted the power of a tribune (tribunicia potestas), though not the title, which allowed him to convene the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and the right to speak first at any meeting. Also included in Augustus' tribunician authority were powers usually reserved for the Roman censor. These included the right to supervise public morals and scrutinize laws to ensure they were in the public interest, as well as the ability to hold a census and determine the membership of the Senate. No Tribune of Rome had held these powers previously, and there was no precedent within the Roman system for combining the powers of the Tribune and the Censor into a single position, nor was Augustus ever elected to the office of Censor. Whether censorial powers were granted to Augustus as part of his tribunician authority, or he simply assumed these responsibilities, is still a matter of debate.

In addition to tribunician authority, Augustus was granted sole imperium within the city of Rome itself: All armed forces in the city, formerly under the control of the Praefects, were now under the sole authority of Augustus. Additionally, Augustus was granted imperium proconsulare maius, or "imperium over all the proconsuls," which translated to the right to interfere in any province and override the decisions of any governor. With maius imperium, Augustus was the only individual able to receive a triumph as he was ostensibly the head of every Roman army.

Many of the political subtleties of the Second Settlement seem to have evaded the comprehension of the Plebeian class. When, in 22 B.C.E., Augustus failed to stand for election as consul, fears arose once again that Augustus, seen as the great "defender of the people," was being forced from power by the aristocratic Senate. In 22, 21, and 20 B.C.E., the people rioted in response, and only allowed a single consul to be elected for each of those years, ostensibly to leave the other position open for Augustus. Finally, in 19 B.C.E., the Senate voted to allow Augustus to wear the consul's insignia in public and before the Senate, with an act sometimes known as the Third Settlement. This seems to have assuaged the populace; regardless of whether or not Augustus was actually a consul, the importance was that he appeared as one before the people.

With these powers in mind, it must be understood that all forms of permanent and legal power within Rome officially lay with the Senate and the people; Augustus was given extraordinary powers, but only as a pronconsul and magistrate under the authority of the Senate. Augustus never presented himself as a king or autocrat, once again only allowing himself to be addressed by the title princeps. After the death of Lepidus in 13 B.C.E., he additionally took up the position of pontifex maximus, the high priest of the collegium of the Pontifices, the most important position in Roman religion.

Later Roman Emperors would generally be limited to the powers and titles originally granted to Augustus, though often, in order to display humility, newly appointed Emperors would often decline one or more of the honorifics given to Augustus. Just as often, as their reign progressed, Emperors would appropriate all of the titles, regardless of whether they had actually been granted by the Senate. The Civic Crown, consular insignia, and later the purple robes of a Triumphant general (toga picta) became the imperial insignia well into the Byzantine era, and were even adopted by many Germanic tribes invading the former Western empire as insignia of their right to rule.

Death and Succession

Augustus' control of power throughout the Empire was so absolute that it allowed him to name his successor, a custom that had been abandoned and derided in Rome since the foundation of the Republic. At first, indications pointed toward his sister's son, Marcus Claudius Marcellus, who had been married to Augustus' daughter Julia the Elder. However, Marcellus died of food poisoning in 23 B.C.E. Reports of later historians that this poisoning, and other later deaths, were caused by Augustus' wife, Livia Drusilla, are inconclusive at best.

After the death of Marcellus, Augustus married his daughter to his right hand man, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. This union produced five children, three sons and two daughters: Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar, Vipsania Julia, Agrippina the Elder, and Postumus Agrippa, so named because he was born after Marcus Agrippa died. Augustus' intent to make the first two children his heirs was apparent when he adopted them as his own children. Augustus also showed favor to his stepsons, Livia's children from her first marriage, Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus and Tiberius Claudius, after they had conquered a large portion of Germany.

After Agrippa died in 12 B.C.E., Livia's son Tiberius divorced his own wife and married Agrippa's widow. Tiberius shared in Augustus' tribune powers, but shortly thereafter went into retirement. After the early deaths of both Gaius and Lucius in 4 and 2 C.E. respectively, and the earlier death of his brother Drusus (9 B.C.E.), Tiberius was recalled to Rome, where he was adopted by Augustus.

On August 19, 14 B.C.E., Augustus died. Postumus Agrippa and Tiberius had been named co-heirs. However, Postumus had been banished, and was put to death around the same time. The one who ordered his death is unknown, but the way was clear for Tiberius to assume the same powers that his stepfather had.

Augustus' famous last words to his friends were, "Since well I've played my part, all clap your hands, and from the stage dismiss me with applause"—a common Greek ending to comedies, referring to the play-acting and regal authority that he had put on as emperor. He died kissing his wife Livia, uttering these last words: "Live mindful of our wedlock, Livia, and farewell."[5]

Legacy

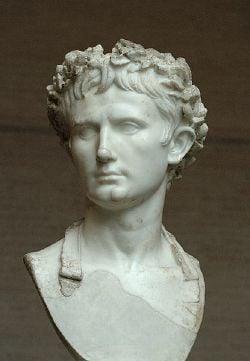

Augustus was deified soon after his death, and both his borrowed surname, Caesar, and his title Augustus became the permanent titles of the rulers of Rome for the next 400 years, and were still in use at Constantinople fourteen centuries after his death. In many languages, caesar became the word for "emperor," as in German (Kaiser), in Dutch (keizer), and in Russian (Tsar). The cult of the Divine Augustus continued until the state religion of the Empire was changed to Christianity in the fourth century. Consequently, there are many excellent statues and busts of the first, and in some ways the greatest, of the emperors. Augustus' mausoleum originally contained bronze pillars inscribed with a record of his life, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, which had also been disseminated throughout the empire during his lifetime.

Many consider Augustus to be Rome's greatest emperor; his policies certainly extended the empire's life span and initiated the celebrated Pax Romana or Pax Augusta. He was handsome, intelligent, decisive, and a shrewd politician, but he was not perhaps as charismatic as Julius Caesar or Mark Antony. Nevertheless, his legacy proved more enduring. He spent a lot of time reorganizing the army and the administration. He organized the army into 25 legions, each of which had 6,100 foot and 726 horse and this remained the strength of the army for 400 years. Consuls and Tribunes were still elected. He himself lived a modest life-style and appeared anxious to be seen as on the same level as his subjects, or citizens. He disliked luxury and wore the plain dress of an ordinary Senator. He was especially anxious to restore the sanctity of marriage.

In looking back on the reign of Augustus and its legacy to the Roman world, its longevity should not be overlooked as a key factor in its success. As one ancient historian says, people were born and reached middle age without knowing any form of government other than the Principate. Had Augustus died earlier (in 23 B.C.E., for instance), matters may have turned out differently. The attrition of the civil wars on the old Republican oligarchy and the longevity of Augustus, therefore, must be seen as major contributing factors in the transformation of the Roman state into a de facto monarchy in these years. Augustus' own experience, his patience, his tact, and his political acumen also played their parts. He directed the future of the empire down many lasting paths, from the existence of a standing professional army stationed at or near the frontiers, to the dynastic principle so often employed in the imperial succession, to the embellishment of the capital at the emperor's expense.

Augustus' ultimate legacy was the peace and prosperity the empire enjoyed for the next two centuries under the system he initiated. His memory was enshrined in the political ethos of the Imperial age as a paradigm of the good emperor, and although every emperor adopted his name, Caesar Augustus, only a handful, such as Trajan, earned genuine comparison with him. His reign laid the foundations of a regime that would last for 250 years.

Caesar Augustus is briefly mentioned in the New Testament at Luke 2:1. As the emperor at the time of Christ's birth, he may be seen as having been providentially ordained to establish a peaceful and prosperous environment for the worldwide expansion of Christ's kingdom.

Month

The month of August (Latin Augustus) is named after Augustus; until his time it was called Sextilis (the sixth month of the Roman calendar). Commonly repeated lore has it that August has 31 days because Augustus wanted his month to match the length of Julius Caesar's July, but this is an invention of the thirteenth century scholar Johannes de Sacrobosco. Sextilis in fact had 31 days before it was renamed, and it was not chosen for its length (see Julian calendar). According to Macrobius, Sextilis was chosen because it was in that month that Augustus first had been elected consul, Egypt had become part of the Roman empire, and the civil wars ended. Also, the eighth month was appropriate for someone who earlier had been named Octavian.[6]

Building projects

Augustus boasted that he "found Rome brick and left it marble." Although this did not apply to the Subura slums, which were still as rickety and fire-prone as ever, he did leave a mark on the monumental topography of the center and of the Campus Martius, with the Ara Pacis sundial using an obelisk of Rome, the Temple of Caesar, the Forum of Augustus with its Temple of Mars Ultor, and also other projects either encouraged by him such as the Theatre of Balbus, Agrippa's construction of the Pantheon or funded by him in the name of others, often relations, for example the Portico of Octavia, Theatre of Marcellus. Even his own mausoleum was built before his death to house members of his family.

Augustus in popular culture

Augustus was ranked #18 on Michael H. Hart's "The 100 list of the most influential figures in history."

Television

- Augustus was played by Roland Culver in the BBC miniseries of 1968, The Caesars.

- Augustus was portrayed in the famous BBC dramatization of Robert Graves' novel I, Claudius by Brian Blessed. (1975)

- Augustus was portrayed in the movie Imperium: Augustus (part of thw Imperium movie series) by Peter O'Toole. (2003)

- In the HBO television series, Rome (2005), Gaius Octavian is portrayed by Max Pirkis. However, in the series, he is wrongly referred to as Octavian, while his name at that time would have been Octavius.

- Augustus was portrayed by Santiago Cabrera in an ABC miniseries called Empire (2005), which took place after the assassination of Caesar.

Literature

- Augustus was a central character in The Sandman #30, "August."

Notes

- ↑ Suetonius, Lives of the 12 Caesars: Augustus. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ↑ H.H. Scullard, From the Gracchi to Nero (London: Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0415025273), p. 163.

- ↑ Scullard, p. 164.

- ↑ Robert Green, Julius Caesar (London: Franklin Watts, 1997, ISBN 0531158128), p. 697.

- ↑ Suetonius, The Life of Augustus The Lives of the Caesars. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia Volume I: Books 1-2. ed. and trans. Robert A. Kaster. (Loeb Classical Library; Bilingual edition, 2011, ISBN 978-0674996496).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Green, Robert. Julius Caesar. London: Franklin Watts, 1997. ISBN 0531158128

- Macrobius. Saturnalia, Volume I: Books 1-2. Edited and translated by Robert A. Kaster. Loeb Classical Library; Bilingual edition, 2011. ISBN 978-0674996496

- Scullard, H.H. From the Gracchi to Nero. London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0415025273

- Suetonius, Gaius Tranquillus. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. BiblioLife, 2009. ISBN 978-0559102509

External links

All links retrieved August 21, 2023.

- The Res Gestae Divi Augusti (The Deeds of Augustus, his own account: complete Latin and Greek texts with facing English translation)

- Suetonius' biography of Augustus, Latin text with English translation

- Cassius Dio's Roman History: Books 45‑56, English translation

- Life of Augustus by Nicolaus of Damascus

- De Imperatoribus Romanis

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.