Ballet

Ballet is a highly stylized dance form that developed into a popular courtly entertainment during the Italian Renaissance, a serious dramatic art in seventeenth century France, and a world-renowned fine art in twentieth century Russia and America. Ballet is best known for its sophisticated techniques, such as pointe work, turn-out of the legs, and high extensions; its graceful, flowing, precise movements; and its ethereal qualities.

In Aristotle's "Poetics," dance was likened to drama and held "to represent men's characters as well as what they do and suffer."[1] In ballet, the expressive, disciplined movement of the human body through carefully choreographed productions enables dancers to advance a dramatic narrative, typically a folk tale, while conveying a range of human emotions. Joys, sorrows, hopes, and ideals are dramatized without words, enabling this art form to speak universally across boundaries of language and culture.

The Origin of ballet

Dance is prominent throughout history. Traditions of narrative dance evolved in China, India, Indonesia, and Ancient Greece. Theatrical dance was well-established in the wider arena of ancient Greek theater. When the Romans conquered Greece, they assimilated Greek dance and theater with their art and culture.[2] While dance continued to be important throughout the Middle Ages, in spite of occasional suppression by the Church, ballet as a recognizable dance form did not emerge until the late 1400s, in Italy. While Italy may be credited with the inception of the ballet tradition, the French enabled it to blossom. Incorporating aspects of Italian ballet, French ballet gained prominence and influenced the dance genre internationally. To this day, the majority of ballet vocabulary originates from French.

The word ballet itself comes from French, and was incorporated into English during the seventeenth century. The French word in turn has its origins in Italian balletto, a diminutive of ballo (dance). Ballet ultimately traces back to Latin ballere, meaning to dance.[3]

Ballet in Italy—"Ballo"

Ballet originated in the Renaissance court as an outgrowth of court pageantry in Italy,[4] Aristocratic weddings were lavish celebrations. Court musicians and dancers collaborated to provide elaborate entertainment for them.[5] Ballet was further shaped by the French ballet de cour, which consisted of social dances performed by the nobility in tandem with music, speech, verse, song, decor, and costume.[6] When Catherine de' Medici, an Italian aristocrat with an interest in the arts, married the French crown's heir, Henry II of France, she brought her enthusiasm for dance to France and provided financial support.

A ballet of the Renaissance would look nothing like a modern performance of Giselle or Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake at Moscow's Bolshoi Theater. Tutus, ballet slippers, and pointe work was as yet unheard of in ballet. The choreography was adapted from court dance steps. Performers dressed in the fashions of the times; for women that meant formal gowns that covered their legs to the ankle.[7] Early ballet was participatory, with the audience joining the dance towards the end.

Domenico da Piacenza was one of the first dancing masters. Along with his students, Antonio Cornazano and Guglielmo Ebreo, he was trained in dance and was responsible for teaching nobles the art. Da Piacenza left one work, De arte saltandi et choreus ducendi (On the Art of Dancing and Conducting Dances), which was compiled by his students.[8]

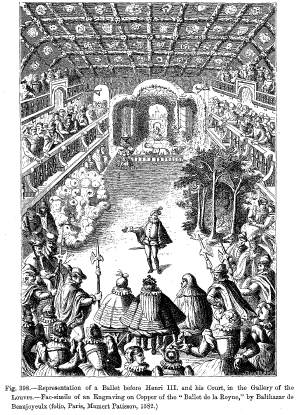

An early ballet, if not the first, produced and shown was Balthasar de Beaujoyeulx's Ballet Comique de la Reine (1581) and was a ballet comique (ballet drama).[9] In the same year, the publication of Fabritio Caroso's Il Ballarino, a technical manual on court dancing, both performance and social, helped to establish Italy as a center of technical ballet development.[10]

France—courtroom dance

Ballet developed as a separate, performance-focused art form in France during the reign of Louis XIV, who was passionate about dance and determined to reverse a decline in dance standards that began in the seventeenth century. Louis XIV established the Académie Royale de la Danse (which evolved into the company known today as the Paris Opera Ballet) in 1661.[11] The earliest references to the five core positions of ballet appear in the writings of Pierre Beauchamp, a court dancer and was also a choreographer.[12]

Jean-Baptiste Lully, an Italian composer serving in the French court, played a significant role in establishing the general direction in which ballet would follow for the next century. Supported and admired by Louis XIV, Lully often cast the king in his ballets. The appellation Sun King, by which the French monarch is still commonly referred, originated from Louis XIV's role in Lully's Ballet de la Nuit (1653).[13] Lully's main contribution to ballet was his nuanced compositions. His understanding of movement and dance allowed him to compose specifically for ballet, with musical phrasings which complemented physical movements.[14] Lully also went on to collaborate with the French playwright Jean-Baptiste Molière. Together, they adapted an Italian theater style, the commedia dell'arte, into their work for a French audience, creating the comédie-ballet. Among their greatest productions was an adaptation of Molière's Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670).[15] Later in life, Lully became the first director of the Académie Royale de Musique after its scope was expanded to include dance.[16] By synthesizing Italian and French dance styles, Jean-Baptiste Lully created a legacy that would define the future of ballet.

Since the first formal ballet school was established in France, dance terminology was crystallized there. Nearly everything in ballet is described by a French word or phrase. (One even bids dancers good luck in French.) Because of the universal terminology, dancers can take a ballet class anywhere in the world and understand the director's instructions.[17]

Russian and Danish ballet

After 1850, interest in ballet began to wane in Paris and grow in Denmark and, most notably, Russia, thanks to masters such as August Bournonville, Jules Perrot, Arthur Saint-Léon, Enrico Cecchetti, and Marius Petipa. The Mariinsky Theater was built in St. Petersburg in 1860, and the Bolshoi Theater even earlier, in 1824. The Imperial Ballet, known after the Bolshevik revolution as the Kirov Ballet (named after the Leningrad party boss, Sergei Kirov), also rose in world prominence.

In the late nineteenth century, colonialism brought new awareness of Asian and African cultures. Orientalism was in vogue, but seen from a colonial perspective, oriental culture was a source of mere fancy. The East was often perceived as a faraway place where anything was possible, provided it was lavish, exotic, and decadent. Petipa appealed to popular taste with The Pharaoh's Daughter (1862), and later The Talisman (1889), and La Bayadère (1877).

Petipa is best remembered for his collaborations with Tchaikovsky, choreographing The Nutcracker (1892, though this is open to some debate among historians), The Sleeping Beauty (1890), and the definitive revival of Swan Lake (1895, with Lev Ivanov), all drawn from western folklore.

The classical tutu, a short skirt supported by layers of crinoline that revealed the dancers' acrobatic legwork, began to appear at this time. Occasionally the tutu revealed more than the audience cared to see and it became customary to wear a leotard as an undergarment.[18]

The choreographer Sergei Diaghilev brought ballet full-circle back to Paris in 1909, when he opened his Ballets Russes, residing first in the Théâtre Mogador and Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris; and then in Monte Carlo. The company sprang from the Russian tsar's Imperial Ballet (also known as the Mariinski Ballet, or the Kirov Ballet) of St. Petersburg, from which all its dancers were associated and trained, under the influence of the great choreographer Marius Petipa. The Ballets Russes created a sensation in Western Europe because of the great vitality of Russian ballet compared with French dance at the time. It became the most influential company in the twentieth century, and that influence, in one form or another, has lasted to the present day. For example, Diaghilev and composer Igor Stravinsky combined their talents to bring Russian folklore to life in The Firebird and Petrushka. And Vaslav Nijinsky became famous for his leaps. The most controversial work of the Ballet Russe was Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, which shocked audiences with its theme of human sacrifice.

After the “golden age” of Petipa, Russian ballet entered a period of stagnation, until choreographer Michel Fokine revitalized the art.[19] Fokine began his career in St. Petersburg but moved to the United States after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Believing that the ballet of the time offered little more than prettiness and athleticism, Fokine demanded drama, expression, and historical authenticity in addition to technical virtuosity. The choreographer, he believed, must research the period and cultural context of the setting and reject the traditional tutu in favor of accurate period costuming. Accordingly, Fokine choreographed Sheherazade and Cleopatra and reworked Petrushka and The Firebird. One of his most famous works was The Dying Swan, performed by prima ballerina Anna Pavlova. Beyond her talents as a ballerina, Pavlova had the theatrical gifts to fulfill Fokine's vision of ballet as drama. Legend has it that Pavlova identified so much with the swan role that she requested her swan costume from her deathbed.

Russian companies, particularly after World War II toured all over the world, revitalizing ballet in the west and elevating it as an art embraced by the general public. In America, choreographer George Balanchine modified the ballet techniques he had learned in his native Russia and brought state-of-the-art technique to America by opening a school in Chicago and later in New York and adapting ballet to new media, specifically film and television.[20] A prolific worker, Balanchine re-choreographed classics such as Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty as well as staging scores of new ballets. He produced original interpretations of the dramas of William Shakespeare such as Romeo and Juliet, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and A Midsummer Night's Dream. In Jewels, Balanchine broke with the narrative tradition in full length ballets and dramatized a theme rather than a plot. Today, partly thanks to Balanchine, ballet is one of the most renowned dance styles in the world.

Barbara Karinska, a Russian emigrant and a skilled seamstress, collaborated with Balanchine to elevate the art of costume design from a secondary role to an integral part of a ballet performance. She introduced the bias cut and a simplified classic tutu that allowed the dancer more freedom of movement. With meticulous attention to detail, she decorated her tutus with beadwork, embroidery, crochet, and appliqué.

Russia gave the world not only great directors, choreographers, and set designers, but most of all, great dancers. In addition to Najinsky and Pavlova, Russia produced many of the twentieth century's great ballet performers, including Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarava, and Mikhail Baryshnikov, among others.

The art of ballet

The eighteenth century saw major advances in the technical standards of ballet, and during this period it came to be regarded as a serious dramatic art form on par with opera. Central to this development was the seminal work of Jean-Georges Noverre. His Lettres sur la danse et les ballets (1760) focused on developing the ballet d'action, in which the movements of the dancers are designed to express character and assist in the narrative. At this time, women played a secondary role as dancers, encumbered as they were with hoops, corsets, wigs, and high heels.

Developments in ballet composition were also advanced by composers such as Christoph Gluck. Finally, ballet was divided into three formal techniques: Sérieux, demi-caractère, and comique. Ballet also began to be featured in operas as interludes called divertissements.

The nineteenth century was a period of great social change, reflected in ballet by a shift away from earlier aristocratic patronage and sensibilities. Ballerinas such as Marie Taglioni and Fanny Elssler pioneered new techniques, such as pointework, that elevated the ballerina into prominence as the ideal stage figure. At the same time, the ballet slipper was invented to support pointe work. Professional librettists began crafting the stories in ballets, and teachers like Carlo Blasis codified ballet technique in the basic form that is still used today.

The rise of Romanticism, a reaction in the arts against Enlightenment rationalism and growing industrialization, led choreographers to compose romantic ballets that were light and airy. These fanciful ballets portrayed women as fragile, unearthly beings; delicate creatures who could be lifted effortlessly. Ballerinas began to wear romantic tutus, with pastel, flowing skirts that bared the shins. The stories revolved around uncanny, folkloric spirits, such as in La Sylphide, one of the oldest romantic ballets still danced today. Starting from La Sylphide, ballerinas also began to dance on their toes, which further enhanced their image as ethereal, unearthly beings.

Neoclassical ballet

Neoclassical ballet describes a dance style that uses traditional ballet vocabulary but is generally more expansive than the classical structure allowed. For example, dancers often dance at more extreme tempos and perform more technical feats. Spacing in neoclassical ballet is usually more modern or complex than in classical ballet. Although organization in neoclassical ballet is more varied, the focus on structure is a defining characteristic of neoclassical ballet.

The neoclassical style of twentieth century ballet was best exemplified by the works of George Balanchine. It drew on the advanced technique of nineteenth century Russian imperial dance, but stripped it of its detailed narrative and dense theatrical setting. What was left was the dance itself, sophisticated but sleekly modern, retaining the pointe shoe aesthetic, but eschewing the involved drama and mime of the full length story ballet.

Tim Scholl, author of From Petipa to Balanchine, considers Balanchine's Apollo (1928) to be the first neoclassical ballet, a return to form in response to Serge Diaghilev's abstract ballets. Although much of Balanchine's work epitomized the genre, British choreographers Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan were also great neoclassical choreographers.

Contemporary ballet

Contemporary ballet is a form of dance influenced by both classical ballet and modern dance. It takes its technique and use of pointework from classical ballet, yet it permits a greater range of movement than the strict body lines set forth by schools of ballet technique. Many of its concepts come from the ideas and innovations of twentieth century modern dance, including floorwork and turn-in of the legs.

While mostly identified with neoclassical ballet, George Balanchine is often thought to have pioneered the techniques of contemporary ballet as well. He used flexed hands (and occasionally feet), turned-in legs, off-centered positions, and non-classical costumes (such as leotards and tunics instead of tutus) to distance himself from the classical and romantic ballet traditions. Balanchine also brought modern dancers like Paul Taylor into his company, the New York City Ballet, as in the 1959 Balanchine ballet, Episodes. Collaborating with modern dance choreographer Martha Graham, Balanchine expanded his exposure to modern techniques and ideas. Also during this period, choreographers such as John Butler and Glen Tetley began to experiment with ballet and modern techniques.

One notable dancer who trained with Balanchine was the Russian emigrant Mikhail Baryshnikov. Following his appointment as artistic director of the American Ballet Theatre in 1980, Baryshnikov worked with various modern choreographers, most notably Twyla Tharp. Tharp choreographed Push Comes To Shove for ABT and Baryshnikov in 1976; in 1986, she created In The Upper Room for her own company. Both were considered innovative for their use of distinctly modern movements melded with the use of pointe shoes and classically-trained dancers.

Tharp also worked with the Joffrey Ballet company, founded in 1957 by Robert Joffrey. She choreographed Deuce Coupe in 1973, using pop music and a blend of modern and classical ballet techniques. The Joffrey Ballet continued to perform numerous contemporary pieces, many choreographed by co-founder Gerald Arpino.

Today, there are many explicitly contemporary ballet companies and choreographers. These include Alonzo King and his company, Alonzo King's LINES Ballet; Nacho Duato and Compañia Nacional de Danza; William Forsythe, who has worked extensively with the Frankfurt Ballet and today runs his own company; and Jiří Kilián, currently the artistic director of the Nederlands Dans Theatre. Traditionally "classical" companies, such as the Kirov Ballet and the Paris Opera Ballet, also regularly perform contemporary works.

Technique

Ballet, especially classical ballet, puts great emphasis on the method and execution of movement.[21] A distinctive feature of ballet is the outward rotation of the thighs from the hip. The foundation of the dance consists of five basic positions, all performed with the turnout.

Young dancers receive a rigorous education in their school's method of dance, which begins at an early age and ends with graduation from high school. Students are required to learn the names, meanings, and precise technique of each movement. Emphasis is put on building strength mostly in the lower body, particularly the legs, and the core (also called the center, or the abdominals) as a strong core is necessary for many movements in ballet, especially turns, and on developing flexibility and strong feet for dancing en pointe.

Ballet techniques are generally grouped by the area in which they originated, such as the high extensions and dynamic turns of Russian ballet. Italian ballet, in contrast, tends to be more grounded, with a heavy focus on fast intricate footwork (eg. the Tarantella is a well known Italian folk dance, which is believed to have influenced Italian ballet). In many cases, ballet methods are named after their originator. In Russia, two of the most notable systems are the Vaganova method, after Agrippina Vaganova, and the Legat Method, after Nikolai Legat; while in Italy, the technique is predominantly the Cecchetti method, after Enrico Cecchetti. Another popular European system from around the same period is the Bournonville method, which originated in Denmark and is named after August Bournonville.

To perform the more demanding routines, a ballet dancer must appear to defy gravity while working within its constraints. Basic physics and the science of human perception provide insight into how this is accomplished. For example, during the grand jeté, the dancer may appear to hover. Physically, his/her center of mass describes a parabola, as does a ball when thrown. When leaping, however, the dancer extends the arms and legs and camouflages the fall, leading the audience to perceive that the dancer is floating. A Pas de Chat (step of the cat) creates a similar illusion. The dancer starts from a plié, then during the ascending phase of the step, quickly lifts each knee in succession with hips turned out, so that for a moment both feet are in the air at the same time, passing each other. For a moment, the dancer appears suspended in air.

The ability of a dancer to seemingly hold a position in mid-air is called ballon. The fall must be performed carefully. The laws of physics decree that momentum must be dissipated, but a crash landing would destroy the impression of airiness and likely injure the dancer. Part of the solution is a floor designed to absorb shock. The dancer also bends at the knees (plies) and rolls the foot from toe to heel. For artistic as well as safety reasons, this technique must be taught by a qualified instructor.

International appeal

Ballet has spread throughout the world, notably in the stagings of the Royal Danish Ballet, the Sadler's Royal Ballet of London, American Ballet Theatre, the Australian Ballet, and more recently the China Central Ballet, Hong Kong Ballet, and the Ballet Company of the New National Theater of Tokyo, as well as the National Ballet Academy and Trust set up in India. The Korean National Ballet (founded in 1962), and more recently Universal Ballet of Seoul, have contributed to the popularization of ballet in Korea. The Universal Ballet invited Oleg Vinogradov, the artistic director of the Kirov Ballet for 22 years, to stage classics from the Kirov repertory starting in 1992, and as artistic director in 1998, thus introducing the Russian ballet style in Korea.

The athleticism and virtuosity of modern ballet has won international recognition. Re-stagings of beloved ballets, as well as innovative modern dance, testify to the flexibility and vitality of the art. Dancers and choreographers constantly seek to explore new technical and dramatic frontiers, and international tours of dance companies and elite schools of dance confirm the continuing global appeal of contemporary ballet.

Notes

- ↑ Aristotle (1920), p. 11

- ↑ Lee (2002), pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Chantrell (2002), p. 42.

- ↑ Kirstein (1952), p. 4.

- ↑ Andros on Ballet, Catherine de' Medici. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ↑ Bland (1976), p. 43.

- ↑ Robert Greskovic, BALLET 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving the Ballet. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ↑ Lee (2002), p. 29.

- ↑ Anderson (1992), p. 32.

- ↑ Lee (2002), p. 54.

- ↑ Bland (1976), p. 49.

- ↑ Mike McGee, The History of Dance. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ↑ Lee (2002), pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Lee (2002), p. 73.

- ↑ Lee (2002), p. 74. Anderson (1992), p. 42.

- ↑ Lee (2002), p. 74.

- ↑ Tom's Dance Page, General Questions about Ballet and Modern Dance. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ RingSurf, Two Types Of Tutu. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Yonkers Historical Society, Michel Fokine, Father of Modern Dance. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ The Balanchine Foundation, George Balanchine. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Kirstein (1952), pp. 6-7, 21.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aristotle. The Poetics, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1920.

- Anderson, Jack. Ballet & Modern Dance: A Concise History, 2nd ed. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Book Company, 1992. ISBN 0871271729

- Bland, Alexander. A History of Ballet and Dance in the Western World. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1976. ISBN 0275537404

- Chantrell, Glynnis, ed. The Oxford Essential Dictionary of Word Histories. New York: Berkley Books, 2002. ISBN 0425190986

- Kirstein, Lincoln and Muriel Stuart. The Classic Ballet. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952.

- Lee, Carol. Ballet In Western Culture: A History of its Origins and Evolution. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- The Bournonville School: The DVD, The Dance Programme, The Music. Copenhagen: The Royal Danish Theatre, 2005.

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.