Battle of Harpers Ferry

| Battle of Harpers Ferry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 1865. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| United States of America | Confederate States of America | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Dixon S. Miles† | Thomas J. Jackson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,000 | 19,900 | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 44 killed 173 wounded 12,419 captured |

39 killed 248 wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Harpers Ferry was fought from September 12 to September 15, 1862, as part of the Maryland Campaign of the American Civil War. As Robert E. Lee's Confederate army invaded Maryland, a portion of his army, under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, surrounded and bombarded the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), capturing its 12,419 soldiers. Jackson's men then rushed to Sharpsburg, Maryland, to rejoin Lee for the Battle of Antietam. Harpers Ferry was a victory for the South. It helped to prolong the bloody struggle that almost crippled the nation, over the preservation of the Union itself. If the South had not suffered final defeat, some believe the the United States would have remained divided. However, in the face of the Northern States' ultimate victory, such battles as Harpers Ferry and the exploits of such generals as Jackson, the South was able to still muster some pride, convinced that it had fought with skill and determination. Without this, the process of reconciliation and of Reconstruction that followed the war's end may have failed. The nation would have remained divided and weakened by Southern resentment and humiliation.

| Maryland Campaign |

|---|

| South Mountain – Harpers Ferry – Antietam – Shepherdstown |

Background

Harpers Ferry (originally Harper's Ferry) is a small town at the confluence of the Potomac River and the Shenandoah River, the site of a historic Federal arsenal (founded by President George Washington in 1799)[1] and a bridge for the critical Baltimore and Ohio Railroad across the Potomac. It was earlier the site of the abolitionist John Brown's attack on the Federal arsenal there, which commenced on October 17, 1859.

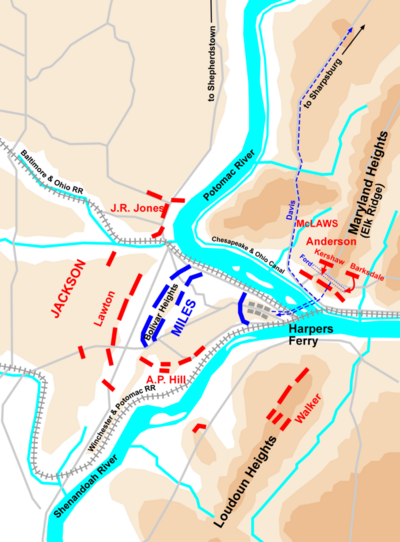

The town was virtually indefensible, dominated on all sides by higher ground. To the west, the ground rose gradually for about a mile and a half to Bolivar Heights, a plateau 668 feet (204 m) high that stretch from the Potomac to the Shenandoah. To the south, across the Shenandoah, Loudoun Heights overlooked from 1,180 feet. And to the northeast, across the Potomac, the southernmost extremity of Elk Ridge formed the 1,476-foot-high crest of Maryland Heights. A Federal soldier wrote that if these three heights could not be held, Harpers Ferry would be "no more defensible than a well bottom."[2]

As Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia advanced into Maryland on September 4, 1862, Lee expected that the Union garrisons that potentially blocked his supply line in the Shenandoah Valley, at Winchester, Martinsburg, and Harpers Ferry, would be cut off and abandoned without firing a shot (and, in fact, both Winchester and Martinsburg were evacuated).[3] But the Harpers Ferry garrison had not retreated. Lee planned to capture the garrison and the arsenal, not only to seize its supplies of rifles and ammunition, but to secure his lines of supplies back to Virginia.

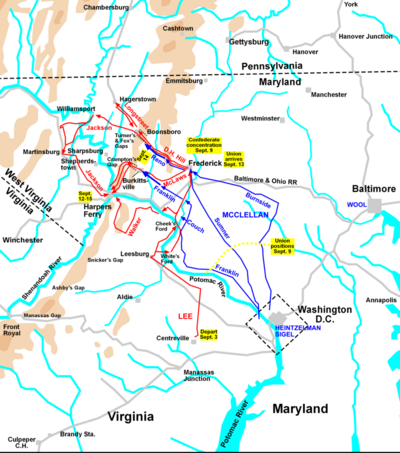

Although he was being pursued at a leisurely pace by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac, outnumbering him more than two to one, Lee chose the risky strategy of dividing his army to seize the prize of Harpers Ferry. While the corps of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet drove north in the direction of Hagerstown, Lee sent columns of troops to converge and attack Harpers Ferry from three directions. The largest column, 11,500 men under Jackson, was to recross the Potomac and circle around to the west of Harpers Ferry and attack it from Bolivar Heights, while the other two columns, under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws (8,000 men) and Brig. Gen. John G. Walker (3,400), were to capture Maryland Heights and Loudoun Heights, respectively, commanding the town from the east and south.[4]

McClellan had wanted to add the Harpers Ferry garrison to his field army, but general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck had refused, saying that the movement would be too difficult and that the garrison had to defend itself "until the latest moment," or until McClellan could relieve it. Halleck had probably expected its commander, Colonel Dixon S. Miles, to show some military knowledge and courage. Miles was a 38-year veteran of the U.S. Army and the Mexican-American War, who had been disgraced after the First Battle of Bull Run when a court of inquiry held that he had been drunk during the battle. Miles swore off liquor and was sent to the supposedly quiet post at Harpers Ferry.[5] His garrison comprised 14,000 men, many inexperienced, including 2,500 who had been forced out of Martinsburg by the approach of Jackson's men on September 11.

On the night of September 11, McLaws arrived at Brownsville, 6 miles northeast of Harpers Ferry. He left 3,000 men near Brownsville Gap to protect his rear and moved 3,000 others toward the Potomac River to seal off any eastern escape route from Harpers Ferry. He dispatched the veteran brigades of Brig. Gens. Joseph B. Kershaw and William Barksdale to seize Maryland Heights on September 12. The other Confederate columns were making slow progress and were behind schedule. Jackson's men were delayed at Martinsburg. Walker's men were ordered to destroy the aqueduct carrying the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal across the Monocacy River where it empties into the Potomac, but his engineers had difficulty demolishing the stone structure and the attempt was eventually abandoned.[6] So the attack on Harpers Ferry that had been planned for September 11 was delayed, increasing the risk that McClellan might engage and destroy a portion of Lee's army while it was divided.

Battle

September 12

Miles insisted on keeping most of the troops near the town instead of taking up commanding positions on the surrounding heights. He apparently was interpreting literally his orders to hold the town. The defenses of the most important position, Maryland Heights, were designed to fight off raiders, but not to hold the heights themselves. There was a powerful artillery battery halfway up the heights: Two 9-inch naval Dahlgren rifles, one 50-pounder Parrott rifle, and four 12-pounder smoothbores. On the crest, Miles assigned Col. Thomas H. Ford of the 32nd Ohio Infantry to command parts of four regiments, 1,600 men. Some of these men, including those of the 126th New York, had been in the Army only 21 days and lacked basic combat skills. They erected primitive breastworks and sent skirmishers a quarter-mile in the direction of the Confederates.[7] On September 12, they encountered the approaching men from Kershaw's South Carolina brigade, who had been moving slowly through the very difficult terrain on Elk Ridge. Rifle volleys from behind abatis caused the Confederates to stop for the night.

September 13

Kershaw began his attack at about 6:30 a.m., September 13. He planned to push his own brigade directly against the Union breastworks while Barksdale's Mississippians flanked the Federal right. Kershaw's men charged into the abatis twice and were driven back with heavy losses. The inexperienced New York troops were holding their own. Their commander, Col. Ford, felt ill that morning and stayed back two miles behind the lines, leaving the fighting to Col. Eliakim Sherrill, the second-ranking officer. Sherrill was wounded by a bullet through the cheek and tongue while rallying his men and had to be carried from the field, making the green troops grow panicky. As Barksdale's Mississippians approached on the flank, the New Yorkers broke and fled rearward. Although Major Sylvester Hewitt ordered the remaining units to reform farther along the ridge, orders came at 3:30 p.m. from Col. Ford to retreat. (In doing so, he apparently neglected to send for the 900 men of the 115th New York, waiting in reserve midway up the slope.) His men destroyed their artillery pieces and crossed a pontoon bridge back to Harpers Ferry. Ford later insisted he had the authority from Miles to order the withdrawal, but a court of inquiry concluded that he had "abandoned his position without sufficient cause," and recommended his dismissal from the Army.[8]

During the fighting on Maryland Heights, the other Confederate columns arrived—Walker to the base of Loudoun Heights at 10 a.m. and Jackson's three divisions (Brig. Gen. John R. Jones to the north, Brig. Gen. Alexander R. Lawton in the center, and Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill to the south) to the west of Bolivar Heights at 11 a.m.—and were astonished to see that these positions were not defended. Inside the town, the Union officers realized they were surrounded and pleaded with Miles to attempt to recapture Maryland Heights, but he refused, insisting that his forces on Bolivar Heights would defend the town from the west. He exclaimed, "I am ordered to hold this place and God damn my soul to hell if I don't." In fact, Jackson's and Miles's forces to the west of town were roughly equal, but Miles was ignoring the threat from the artillery massing to his northeast and south.

Late that night, Miles sent Captain Charles Russell of the 1st Maryland Cavalry with nine troopers to slip through the enemy lines and take a message to McClellan, or any other general he could find, informing them that the besieged town could hold out only for 48 hours. Otherwise, he would be forced to surrender. Russell's men slipped across South Mountain and reached McClellan's headquarters at Frederick. The general was surprised and dismayed to receive the news. He wrote a message to Miles that a relief force was on the way and told him, "Hold out to the last extremity. If it is possible, re-occupy the Maryland Heights with your whole force." McClellan ordered Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin and his VI Corps to march from Crampton's Gap to relieve Miles. Although three couriers were sent with this information on different routes, none of them reached Harpers Ferry in time.[9]

September 14

While battles raged at the passes on South Mountain, Jackson had methodically positioned his artillery around Harpers Ferry. This included four Parrott rifles to the summit of Maryland Heights, a task that required 200 men wrestling the ropes of each gun. Although Jackson wanted all of his guns to open fire simultaneously, Walker on Loudoun Heights grew impatient and began an ineffectual bombardment with five guns shortly after 1 p.m. Jackson ordered A.P. Hill to move down the west bank of the Shenandoah in preparation for a flank attack on the Federal left the next morning.[10]

That night, the Union officers realized they had less than 24 hours left, but they made no attempt to recapture Maryland Heights. Unbeknownst to Miles, only a single Confederate regiment now occupied the crest, after McLaws had withdrawn the remainder to meet the Union assault at Crampton's Gap.

Col. Benjamin F. "Grimes" Davis proposed to Miles that his troopers of the 12th Illinois Cavalry, and some smaller units from Maryland and Rhode Island, attempt to break out. Cavalry forces were essentially useless in the defense of the town. Miles dismissed the idea as "wild and impractical," but Davis was adamant and Miles relented when he saw that the fiery Mississippian intended to break out, with or without permission. Davis and Col. Amos Voss led their 1,400 cavalrymen out of Harpers Ferry on a pontoon bridge across the Potomac, turning left onto a narrow road that wound to the west around the base of Maryland Heights in the north toward Sharpsburg. Despite a number of close calls with returning Confederates from South Mountain, the cavalry column encountered a wagon train approaching from Hagerstown with James Longstreet's reserve supply of ammunition. They were able to trick the wagoneers into following them in another direction and they repulsed the Confederate cavalry escort in the rear of the column. Capturing more than 40 enemy ordnance wagons, Davis had lost not a single man in combat, the first great cavalry exploit of the war for the Army of the Potomac.[11] (It would also be the last major success of the Union Army in the debacle at Harpers Ferry.)

September 15

By the morning of September 15, Jackson had positioned nearly 50 guns on Maryland Heights and at the base of Loudoun Heights, prepared to enfilade the rear of the Federal line on Bolivar Heights. Jackson began a fierce artillery barrage from all sides and ordered an infantry assault for 8 a.m. Miles realized that the situation was hopeless. He had no expectation that relief would arrive from McClellan in time and his artillery ammunition was in short supply. At a council of war with his brigade commanders, he agreed to raise the white flag of surrender. But he would not be personally present at any ceremony. He was confronted by a captain of the 126th New York Infantry, who said, "For ——'s sake, Colonel, don't surrender us. Don't you hear the signal guns? Our forces are near us. Let us cut our way out and join them." But Miles replied, "Impossible. They will blow us out of this place in half an hour." As the captain turned away in disdain, a shell exploded, shattering Miles's left leg. So disgusted were the men of the garrison with Miles's behavior, which some claimed involved being drunk again, it was difficult to find a man who would take him to the hospital. He was mortally wounded and died the next day. Some historians have speculated that Miles was struck deliberately by fire from his own men.[12]

Aftermath

Jackson had won a great victory at minor expense. Killed and wounded were 217 on the Union side, 286 Confederate, mostly from the fighting on Maryland Heights.[13] The Union garrison surrendered 12,419 men, 13,000 small arms, 200 wagons, and 73 artillery pieces.[14] The magnitude of the surrender of U.S. troops was not matched until the Battle of Corregidor during World War II.

Confederate soldiers feasted on Union food supplies and helped themselves to fresh blue Federal uniforms, which would cause some confusion in the coming days. About the only unhappy men in Jackson's force were the cavalrymen, who had hoped to replenish their exhausted mounts.

Jackson sent off a courier to Lee with the news. "Through God's blessing, Harper's Ferry and its garrison are to be surrendered." As he rode into town to supervise his men, Union soldiers lined the roadside, eager for a look at the famous Stonewall. One of them observed Jackson's dirty, seedy uniform and remarked, "Boys, he isn't much for looks, but if we'd had him we wouldn't have been caught in this trap."[15] By early afternoon, Jackson received an urgent message from General Lee: Get your troops to Sharpsburg as quickly as possible. Jackson left A.P. Hill at Harpers Ferry to manage the parole of Federal prisoners and began marching to join the Battle of Antietam. Harpers Ferry would prove a vital stronghold for the Confederate Army as it marched into Maryland, as it provided a base for funneling in troops to Lee's army in Antietam and thwarting defeat there.

Notes

- ↑ Robert S. Wolff, "Harper's Ferry, (West) Virginia," in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, eds. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 928.

- ↑ Ronald H. Bailey and Time-Life Books, The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam (Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1984), 39.

- ↑ Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983), 83.

- ↑ Bailey, 38-39.

- ↑ Sears, 89.

- ↑ Sears, 95.

- ↑ Sears, 122-23.

- ↑ Bailey, 43.

- ↑ Sears, 133.

- ↑ Bailey, 56.

- ↑ Bailey, 58.

- ↑ David J. Eicher, The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 347.

- ↑ National Park Service, Harpers Ferry. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ Bailey, 59.

- ↑ Sears, 154.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bailey, Ronald H. and Time-Life Books. The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam. Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1984. ISBN 0809447401

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684849445

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. Frederick A. Praeger, 1959.

- Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 089919172X

- Wolff, Robert S. "Harper's Ferry, (West) Virginia." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, 928-30. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 039304758X

External links

All links retrieved September 22, 2023.

- Harpers Ferry at Son of the South

- West Virginia Civil War Battles - Harpers Ferry

- Maps and aerial photos

- Street map from Google Maps or Yahoo! Maps

- Topographic map from TopoZone

- Satellite image from Google Maps or Microsoft Virtual Earth

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.