Battle of Inchon

| Battle of Inchon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean War | |||||||

Four tank landing ships unload men and equipment on Red Beach one day after the amphibious landings in South Korea. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000 total combat troops | 1000 men on the beaches,5000 in Seoul and 500 in the near airport of Kimpo | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 222 killed | 1350 killed,unknown captured | ||||||

The Battle of Inchon (also Romanized as "Incheon;" Korean: 인천 상륙 작전 Incheon Sangryuk Jakjeon; code name: Operation Chromite) was a decisive invasion and battle during the Korean War, conceived and commanded by U.S. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. It was deemed extremely risky, but today is considered one of the most successful military operations of modern times.

The battle began on September 15, 1950, and ended around September 28. During the amphibious operation, United Nations (UN) forces secured Inchon and broke out of the Busan region through a series of landings in enemy territory. The majority of UN ground forces participating in this assault were U.S. Marines.

| Korean War |

|---|

| Ongjin Peninsula – Uijeongbu – Munsan – Chuncheon/Hongcheon – Gangneung – Miari – Han River – Osan – Donglakri – Danyang – Jincheon – Yihwaryeong – Daejeon – Pusan Perimeter – Inchon – Pakchon – Chosin Reservoir – Faith – Twin Tunnels – Ripper – Courageous – Tomahawk – Yultong Bridge – Imjin River – Kapyong – Bloody Ridge – Heartbreak Ridge – Sunchon – Hill Eerie – Sui-ho Dam – White Horse – Old Baldy – The Hook – Pork Chop Hill – Outpost Harry– 1st Western Sea– 2nd Western Sea |

The Battle of Inchon reversed the near-total occupation of the peninsula by the invading North Korean People's Army (NKPA) and began a counterattack by UN forces that led to the recapture of Seoul. The advance north ended near the Yalu River, when China's People's Volunteer Army, faced with the complete loss of Korea from the communist camp as well as a perceived threat to China's security, entered the conflict by deploying approximately 150,000 Chinese troops in support of North Korea. Chinese forces overran UN forces along the Ch'ongch'on River and forced a withdrawal after the Battle of Chosin Reservoir to South Korea. After the Chinese entered the war, a stalemate generally ensued, resulting in the permanent division of the country into North and South near the 38th parallel. It remains one of the political hot spots in the world, and a dividing line between democracy and the remnants of communism.

Background

Planning

The idea to land UN forces at Inchon was proposed by General MacArthur after he visited the Korean battlefield on June 29, 1950, four days after the war began. MacArthur thought that the North Korean army would push the South Korean army back far past Seoul. He decided that the battered, demoralized, and under-equipped South Koreans could not hold off the NKPA's advances even with American reinforcements. MacArthur felt that he could turn the tide if he made a decisive troop movement behind enemy lines. He hoped that a landing near Inchon would allow him to cut off the NKPA and destroy that army as a useful fighting force, thus winning the war.

To accomplish such a large amphibious operation, MacArthur requested the use of United States Marine Corps expeditionary forces, having become familiar with their ability to integrate amphibious operations in the Pacific during World War II. However, the Marines at that point were still recovering from a series of severe program cutbacks instituted by the Truman administration and Secretary of Defense, Louis A. Johnson. Indeed, Johnson had tried to eliminate the Marines entirely and slashed Marine expeditionary forces from a World War II peak of 300,000 men to just over 27,000. Much of the Marines' landing craft and amphibious carriers had been sold off, scrapped, or transferred to the exclusive use of the U.S. Army. After hastily re-equipping Marine forces with aging World War II landing craft, withdrawing Marine units from the Pusan perimeter, and stripping recruitment depots bare of men, Marine commanders were just able to mount a force capable of undertaking offensive operations.[1]

MacArthur decided to use the Joint Strategic and Operations Group (JSPOG) of his Far East Command (FECOM). The initial plan was met with skepticism by the other generals because Inchon's natural and artificial defenses were formidable. The approaches to Inchon were two restricted passages, Flying Fish and Eastern channels, which could be easily blocked by mines. The current of the channels was also dangerously quick—three to eight knots. Finally, the anchorage was small and the harbor surrounded by tall seawalls. Commander Arlie G. Capps noted, "We drew up a list of every natural and geographic handicap—and Inchon had 'em all."

These problems, along with the advancing North Korean army, forced MacArthur to abandon his first plan, Operation Bluehearts, which called for an Inchon landing in July 1950.

Despite these obstacles, in September, MacArthur issued a revised plan of assault on Inchon: Plan 100-B, codenamed Operation Chromite. A briefing led by Admiral James Doyle concluded "the best that I can say is that Inchon is not impossible." Officers at the briefing spent much of their time asking about alternative landing sites, such as Kunsan. MacArthur spent 45 minutes after the briefing explaining his reasons for choosing Inchon. He said that because it was so heavily defended, the enemy would not expect an attack there, that victory at Inchon would avoid a brutal winter campaign, and that, by invading a northern strong point, the UN forces could cut off North Korean lines of communication. Inchon was also chosen because of its proximity to Seoul. Admiral Forrest P. Sherman and General J. Lawton Collins returned to Washington, D.C., and had the invasion approved.

The landing at Inchon was not the first large-scale amphibious operation since World War II. That distinction belonged to the July 18, 1950, landing at Pohang. However, that operation was not made in enemy held territory and was unopposed.[2]

Before the landing

Seven days before the main attack on Inchon, a joint Central Intelligence Agency–military intelligence reconnaissance, codenamed Trudy Jackson, placed a team of guerrillas in Inchon. The group, led by Navy Lieutenant Eugene Clark, landed at Yonghung-do, an island in the mouth of the harbor. From there, they relayed intelligence back to U.S. forces.

With the help of locals, the guerrillas gathered information about tides, mudflats, seawalls, and enemy fortifications. The mission's most important contribution was the restarting of a lighthouse on Palmi-do. When the North Koreans discovered that the allied agents had entered the peninsula, they sent an attack craft with 16 infantrymen. Eugene Clark mounted a machine gun on a sampan and sank the attack boat. In response, the North Koreans killed up to 50 civilians for helping Clark.

A series of drills and tests were conducted elsewhere on the coast of Korea, where conditions were similar to Inchon, before the actual invasion. These drills were used to perfect the timing and performance of the landing craft.

As the landing groups neared, cruisers and destroyers from several UN navies shelled Wolmi-do and checked for mines in Flying Fish Channel. The first Canadian forces entered the Korean War when HMCS Cayuga, HMCS Athabaskan, and HMCS Sioux bombarded the coast. The Fast Carrier Force flew fighter cover, interdiction, and ground attack missions. Destroyer Squadron Nine, headed by the USS Mansfield, sailed up Eastern Channel and into Inchon Harbor, where it fired upon enemy gun emplacements. The attacks tipped off the North Koreans that a landing might be imminent. The North Korean officer at Wolmi-do assured his superiors that he would throw the enemy back into the sea.

Battle

The flotilla of ships that landed during the battle was commanded by Arthur Dewey Struble, an expert in amphibious warfare. Struble had participated in amphibious operations during World War II, including the Battle of Leyte and the Battle of Normandy.[3]

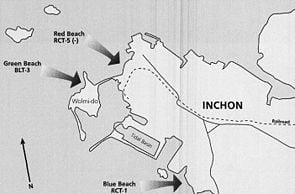

Green Beach

At 6:30 am on September 15, 1950, the lead elements of U.S. X Corps hit "Green Beach" on the northern side of Wolmi-Do Island. The landing force consisted of the 3rd Battalion 5th Marines and nine M26 Pershing tanks from the 1st Tank Battalion. One tank was equipped with a flamethrower (flame tank) and two others had bulldozer blades. The battle group landed in LSTs designed and built during World War II. The entire island was captured by noon at the cost of just 14 casualties.[4] North Korean casualties included over 200 killed and 136 captured, primarily from the 918th Artillery Regiment and the 226th Independent Marine Regiment. The forces on Green Beach had to wait until 7:50 p.m. for the tide to rise, allowing another group to land. During this time, extensive shelling and bombing, along with anti-tank mines placed on the only bridge, kept the North Koreans from launching a significant counterattack. The second wave came ashore at "Red Beach" and "Blue Beach."

The North Korean army had not been expecting an invasion at Inchon. After the storming of Green Beach, the NKPA assumed (probably because of deliberate misinformation by American counter-intelligence) that the main invasion would happen at Kunsan. As a result, only a small force was diverted to Inchon. Even those forces were too late, and they arrived after the UN forces had taken Blue and Red Beaches. The troops already stationed at Inchon had been weakened by Clark's guerrillas, and napalm bombing runs had destroyed key ammunition dumps. In total, 261 ships took part.

Red Beach

The Red Beach forces, made up of the Regimental Combat Team 5, used ladders to scale the sea walls. After neutralizing North Korean defenses, they opened the causeway to Wolmi-Do, allowing the tanks from Green Beach to enter the battle. Red Beach forces suffered eight dead and 28 wounded.

Blue Beach

Under the command of Colonel Lewis "Chesty" Puller, the 1st Marine Regiment landing at Blue Beach was significantly south of the other two beaches and reached shore last. As they approached the coast, the combined fire from several NKPA gun emplacements sank one LST. Destroyer fire and bombing runs silenced the North Korean defenses. When they finally arrived, the North Korean forces at Inchon had already surrendered, so the Blue Beach forces suffered few casualties and met little opposition. The 1st Marine Regiment spent much of its time strengthening the beachhead and preparing for the inland invasion.

Aftermath

Beachhead

Immediately after North Korean resistance was extinguished in Inchon, the supply and reinforcement process began. Seabees and Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) that had arrived with the U.S. Marines constructed a pontoon dock on Green Beach and cleared debris from the water. The dock was then used to unload the remainder of the LSTs.

Documents written by North Korean leader Kim Il Sung and recovered by UN troops soon after the landing said, "The original plan was to end the war in a month, we could not stamp out four American divisions… We were taken by surprise when United Nations troops and the American Air Force and Navy moved in."

On September 16, the North Koreans, realizing their blunder, sent six columns of T-34 tanks to the beachhead. In response, two flights from F4U Corsair squadron VMF-214 bombed the attackers. The air strike damaged or destroyed half of the tank column and lost one plane. A quick counter-attack by M26 Pershing tanks destroyed the remainder of the North Korean armored division and cleared the way for the capture of Inchon.

On September 19, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers repaired the local railroad up to eight miles (13 km) inland. The Kimpo airstrip was captured, and transport planes began flying in gasoline and ordnance for the aircraft stationed at Inchon. The Marines continued unloading supplies and reinforcements. By September 22, they had unloaded 6,629 vehicles and 53,882 troops, along with 25,512 tons (23,000 tonnes) of supplies.

Battle of Seoul

In contrast to the quick victory at Inchon, the advance on Seoul was slow and bloody. The NKPA launched another T-34 attack, which was trapped and destroyed, and a Yak bombing run in Inchon harbor, which did little damage. The NKPA attempted to stall the UN offensive to allow time to reinforce Seoul and withdraw troops from the south. Though warned that the process of taking Seoul would allow remaining NKPA forces in the south to escape, MacArthur felt that he was bound to honor promises given to the South Korean government to retake the capital as soon as possible.

On the second day, vessels carrying the U.S. Army's 7th Infantry Division arrived in Inchon Harbor. General Edward "Ned" Almond was eager to get the division into position to block a possible enemy movement from the south of Seoul. On the morning of September 18, the division's 2nd Battalion of the 32nd Infantry Regiment landed at Inchon and the remainder of the regiment went ashore later in the day. The next morning, the 2nd Battalion moved up to relieve a U.S. Marine battalion occupying positions on the right flank south of Seoul. Meanwhile, the 7th Division's 31st Regiment came ashore at Inchon. Responsibility for the zone south of Seoul highway passed to 7th Division at 6:00 pm on September 19. The 7th Infantry Division then engaged in heavy fighting on the outskirts of Seoul.

Before the battle, North Korea had just one understrength division in the city, with the majority of its forces south of the capital.[5] MacArthur personally oversaw the 1st Marine Regiment as it fought through North Korean positions on the road to Seoul. Control of Operation Chromite was then given to Major General Edward Almond, the X Corps commander. It was Almond's goal to take Seoul on September 25, exactly three months after the beginning of the war. On September 22, the Marines entered Seoul to find it heavily fortified. Casualties mounted as the forces engaged in desperate house-to-house fighting. Anxious to pronounce the conquest of Seoul, Almond declared the city liberated on September 25 despite the fact that Marines were still engaged in house-to-house combat (gunfire and artillery could still be heard in the northern suburbs).

Breakout of Pusan

The last North Korean troops in South Korea still fighting were defeated when General Walton Walker's 8th Army broke out of the Pusan perimeter, joining the Army's X Corps in a coordinated attack on NKPA forces. Of the 70,000 NKPA troops around Pusan, more than half were killed or captured. However, because UN forces had concentrated on taking Seoul rather than cutting off the NKPA's withdrawal north, the remaining 30,000 North Korean soldiers escaped to the north across the Yalu River, where they were soon reconstituted as a cadre for the formation of new NKPA divisions hastily re-equipped by the Soviet Union. The allied assault continued north to the Yalu River until the intervention of the People's Republic of China in the war.

Popular culture

The Battle of Inchon was the subject of the 1981 movie, Inchon, featuring Sir Laurence Olivier, although it did poorly critically and at the box office amid controversy over it being financed by a company, One Way Productions, affiliated with Unification Church leader Rev. Sun Myung Moon. A companion novel, Oh, Inchon! by Robin Moore, was also published.

The battle was briefly featured in the 1977 film, MacArthur, starring Gregory Peck.

The song "Inchon," by Robert W. Smith, depicts the battle.

The W.E.B. Griffin novel, Under Fire, gives a fictionalized account of the political and personal maneuvering that occurred during MacArthur's development of the Inchon invasion plan.

Notes

- ↑ Clay Blair, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950–1953 (Naval Institute Press, 2003).

- ↑ "Landings By Sea Not New In Korea," The New York Times (page 3).

- ↑ "United States Marines Headed For Seoul," September 18, 1950, The New York Times (page 1).

- ↑ Joseph H. Alexander and Don Horan, The Battle History of the U.S. Marines: A Fellowship of Valor (HarperCollins, 1999, ISBN 0-06-093109-4).

- ↑ Hanson W. Baldwin, "Invasion Gamble Pays Off," The New York Times, September 27, 1950.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ballard, John R. "Operation Chromite: Counterattack at Inchon." Joint Forces Quarterly (Spring/Summer 2001).

- Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950–1953. New York: Times Books, 1988. ISBN 0812916700

- Bradford, Jeffrey A. "MacArthur, Inchon and the Art of Battle Command." Military Review 81(2) (2001): 83–86.

- Clark, Eugene Franklin. The Secrets of Inchon: The Untold Story of the Most Daring Covert Mission of the Korean War. New York: Putnam. 2002. ISBN 039914871X

- Edwards, Paul M. The Inchon Landing, Korea, 1950: An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1994. ISBN 0313291357

- Giesler, Patricia. "The Landing at Inchon." Valour Remembered: Canadians in Korea. Veterans Affairs Canada, 1982. ISBN 9780662521150

- Haig, Alexander M., Jr. Inner Circles: How America Changed the World, A Memoir. New York: Warner Books, 1992. ISBN 044651571X

- Halberstam, David. The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York: Hyperion, 2007. ISBN 9781401300524

- Heefner, Wilson A. "The Inch'on Landing." Military Review. 1995 75(2): 65–77.

- Langley, Michael. Inchon Landing: MacArthur's Last Triumph. New York: Times Books, 1979. ISBN 081290821X

- Montross, Lynn, et. al. History of U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950–1953. Austin, TX: R.J. Speights, 1990-1992. ISBN 9780944495056

- Pearlman, Michael D. Truman and MacArthur: Policy, Politics, and the Hunger for Honor and Renown. Bloomington. IN: Indiana University Press, 2008. ISBN 0253350662

- Schnabel, James F. United States Army in the Korean War: Policy and Direction: The First Year. Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1972.

- Simmons, Edwin H. Over the Seawall: US Marines at Inchon. Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Center, 2000.

- Stolfi, Russel H. S. "A Critique of Pure Success: Inchon Revisited, Revised, and Contrasted." Journal of Military History 68(2) (2004).

External links

All links retrieved September 22, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.