Battle of Port Arthur

| Battle of Port Arthur (naval) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Japanese War | |||||||

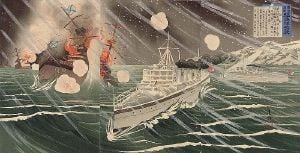

Japanese ukiyoe woodblock print of the night attack on Port Arthur. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Admiral Heihachiro Togo Vice Admiral Shigeto Dewa |

Oskar Victorovich Stark | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15 battleships and cruisers with escorts | 12 battleships and cruisers with escorts | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 90 men and slight damage | 150 men and seven ships damaged | ||||||

The Battle of Port Arthur (Japanese: RyojunkÅ Heisoku Sakusen, February 8-9, 1904) was the starting battle of the Russo-Japanese War. It began with a surprise night attack by a squadron of Japanese destroyers on the Russian fleet anchored at Port Arthur, Manchuria, and continued with an engagement of major surface combatants the following morning. The battle ended inconclusively, and further skirmishing off of Port Arthur continued until May 1904. The battle was set in the wider context of the rival imperialist ambitions of Russian Empire and Empire of Japan, in Manchuria and Korea. Although neither side won, the battle placed Japan onto the world-stage. Japan's subsequent defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese world shocked many who had thought European power invincible. This also laid the foundation for Japan's entry into World War II as a major Eastern ally of Germany.

| Russo-Japanese War |

|---|

| 1st Port Arthur âChemulpo Bay âYalu River â Nanshan â Telissu â Yellow Sea â Ulsan â 2nd Port Arthur â Motien Pass â Tashihchiaoâ Hsimuchengâ Liaoyang â Shaho â Sandepu â Mukden â Tsushima |

Background

The opening stage of the Russo-Japanese War began with preemptive strikes by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the Russian Pacific Fleet based at Port Arthur and at Chemulpo.

Admiral Togo's initial plan was to swoop down upon Port Arthur with the 1st Division of the Combined Fleet, consisting of the battleships Hatsuse, Shikishima, Asahi, Fuji, and Yashima, led by the flagship Mikasa, and the Second Division, consisting of the cruisers Iwate, Azuma, Izumo, Yakumo, and Tokiwa. These capital ships were accompanied by some 15 destroyers and around 20 smaller torpedo boats. In reserve were the cruisers Kasagi, Chitose, Takasago, and Yoshino. With this overwhelming force and surprise on his side, he hoped to deliver a crushing blow to the Russian fleet soon after the severance of diplomatic relations between the Japanese and Russian governments.

On the Russian side, Admiral Stark had the battleships Petropavlovsk, Sevastopol, Peresvet, Pobeda, Poltava, Tsesarevich, and Retvizan, supported by the cruisers Pallada, Diana, Askold, Novik, and Boyarin, all based within the protection of the fortified naval base of Port Arthur. However, the defenses of Port Arthur were not as strong as they could have been, as few of the shore artillery batteries were operational, funds for improving the defenses had been diverted to nearby Dalny, and most of the officer corps was celebrating at a party being hosted by Admiral Stark on the night of February 9, 1904.

As Admiral Togo had received false information from local spies in and around Port Arthur that the garrisons of the forts guarding the port were on full alert, he was unwilling to risk his precious capital ships to the Russian shore artillery and therefore held back his main battle fleet. Instead, the destroyer force was split into two attack squadrons, one squadron with the 1st, 2nd and 3rd flotillas to attack Port Arthur and the other squadron with the 4th and 5th flotillas to attack the Russian base at Dalny.

The night attack of February 8-9, 1904

At about 10:30 p.m. on February 8, 1904, the Port Arthur attack squadron of ten destroyers encountered patrolling Russian destroyers. The Russians were under orders not to initiate combat, and turned to report the contact to headquarters. However, as a result of the encounter, two Japanese destroyers collided and fell behind and the remainder became scattered. At about 12:28 a.m. on February 9, 1904, the first four Japanese destroyers approached the port of Port Arthur without being observed, and launched a torpedo attack against the Pallada (which was hit amidship, caught fire, and keeled over) and the Retvizan (which was holed in her bow). The other Japanese destroyers were less successful, as they arrived too late to benefit from surprise, and made their attacks individually rather than in a group. However, they were able to disable the most powerful ship of the Russian fleet, the battleship Tsesarevitch. The Japanese destroyer Oboro made the last attack, around 2:00 a.m., by which time the Russians were fully awake, and their searchlights and gunfire made accurate and close range torpedo attacks impossible.

Despite ideal conditions for a surprise attack, the results were relatively poor. Of the sixteen torpedoes fired, all but three either missed or failed to explode. But luck was against the Russians in so far as two of the three torpedoes hit their best battleships: The Retvizan and the Tsesarevich were put out of action for weeks, as was the protected cruiser Pallada.

Surface engagement of February 9, 1904

Following the night attack, Admiral Togo sent his subordinate, Vice Admiral Shigeto Dewa, with four cruisers on a reconnaissance mission at 8:00 a.m. to look into the Port Arthur anchorage and to assess the damage. By 9:00 a.m., Admiral Dewa was near enough to make out the Russian fleet through the morning mist. He observed 12 battleships and cruisers, three or four of which seemed to be badly listing or to be aground. The smaller vessels outside the harbor entrance were in apparent disarray. Dewa approached to about 7,500Â yards (6,900Â m) of the harbor, but as no notice was taken of the Japanese ships, he was convinced that the night attack had successfully paralyzed the Russian fleet, and sped off to report to Admiral Togo. Since Dewa had approached no nearer than 3Â nautical miles (6Â km), it is no wonder that his conclusion was wrong.

Unaware that the Russian fleet was getting ready for battle, Dewa urged Admiral Togo that the moment was extremely advantageous for the main fleet to quickly attack. Although Togo would have preferred luring the Russian fleet away from the protection of the shore batteries, Dewa's mistakenly optimistic conclusions meant that the risk was justified. Admiral Togo ordered the First Division to attack the harbor, with the Third Division in reserve in the rear.

Upon approaching Port Arthur the Japanese came upon Russian cruiser Boyarin, which was on patrol. Boyarin fired on the Mikasa at extreme range, then turned and fled. At 11:00 a.m., at a distance of around 8,000Â yards (7,000Â m), combat commenced between the Japanese and Russian fleets. The Japanese concentrated the fire of their 12" guns on the shore batteries while using their 8" and 6" against the Russian ships. Shooting was poor on both sides, but the Japanese severely damaged the Novik, Petropavlovsk, Poltava, Diana, and Askold. However, it soon became evident that Admiral Dewa had made a critical error. In the first five minutes of the battle Mikasa was hit by a ricocheting shell, which burst over her, wounding the chief engineer, the flag lieutenant, and five other officers and men, wrecking the aft bridge.

At 12:20 p.m., Admiral Togo decided to reverse course and escape the trap. It was a highly risky maneuver that exposed the fleet to the full brunt of the Russian shore batteries. Despite the heavy firing, the Japanese battleships completed the maneuver and rapidly withdrew out of range. The Shikishima, Iwate, Fuji, and Hatsuse all took damage. Several hits were also made on Admiral Hikonojo Kamimura's cruisers as they reached the turning point. At this time Novik closed to within 3,300Â yards (3,000Â m) of the Japanese cruisers and fired a torpedo salvo. All missed and Novik received a severe hit below the waterline.

Outcome

The naval Battle of Port Arthur thus ended inconclusively. The Russians took 150 casualties to around 132 for the Japanese. Although no ship was sunk on either side, several took damage. However, the Japanese had ship repair and drydock facilities in Sasebo with which to make repairs, whereas the Russian fleet had only very limited repair capability at Port Arthur.

It was obvious that Admiral Dewa had failed to press his reconnaissance closely enough, and that once the true situation was apparent, Admiral Togo's objection to engage the enemy under their shore batteries was justified. The formal declaration of war between Japan and Russia was issued on February 10, 1904, a day after the battle.

On February 11, 1904, the Russian minelayer Yeneisei started to mine the entrance to Port Arthur. One of the mines washed up against the ship's rudder, exploded and caused the ship to sink, with loss of 120 of the ship's complement of 200. The Yeneisei also sank with the only map indicating the position of the mines. The Boyarin, sent to investigate the accident, also struck a mine and had to be abandoned.

Admiral Togo set sail from Sasebo again on February 14, 1904, with all ships except for the Fuji. On the morning of February 24, 1904, an attempt was made to scuttle five old transport vessels to block the entry to Port Arthur, sealing the Russian fleet inside. The plan was foiled by the Retvizan, which was still grounded outside the harbor. In the poor light, the Russian mistook the old transports for battleships, and an exultant Viceroy Alexeiev telegraphed the Tsar of his great naval victory. After daylight revealed the truth, a second telegram needed to be sent.

On March 8, 1904, Russian Admiral Stepan Makarov arrived in Port Arthur to assume command from the unfortunate Admiral Stark, thus raising Russian morale. He raised his flag on the newly repaired Askold. On the morning of March 10, 1904, the Russian fleet took to the offense, and attacked the blockading Japanese squadron, but to little effect. In the evening of March 10, 1904, the Japanese attempted a ruse by sending four destroyers close to the harbor. The Russians took the bait, and sent out six destroyers in pursuit; whereupon the Japanese mined the entrance to the harbor and moved into position to block the destroyers return. Two of the Russian destroyers were sunk, despite efforts by Admiral Makarov to come to their rescue.

On March 22, 1904, the Fuji and the Yashima were attacked by the Russian fleet under Admiral Makarov, and the Fuji was forced to withdraw to Sasebo for repairs. Under Makarov, the Russian fleet was growing more confident and better trained. In response, on March 27, 1904, Togo again attempted to block Port Arthur, this time using four more old transports filled with stones and cement. The attack again failed as the transports were sunk too far away from the entrance to the harbor.

On April 13, 1904, Makarov (who had now transferred his flag to the Petropavlovsk) left port to go to the assistance of a destroyer squadron he had sent on reconnaissance north to Dalny. He was accompanied by the Askold, Diana, Novik, Poltava, Sevastopol, Pobieda, and Peresvyet. The Japanese fleet was waiting, and Makarov withdrew to the protection of the shore batteries at Port Arthur. However, the area had been mined by the Japanese. At 09:43 a.m., the Petropavlovsk struck 3 mines, exploded, and sank within two minutes. The disaster killed 635 men and officers, along with Admiral Makarov. At 10:15 a.m., the Pobieda was also crippled by a mine. The following day, Admiral Togo orders all flags to be flown at half mast, and that a dayâs mourning be observed for his fallen enemy adversary.

On May 3, 1904, Admiral Togo made his third and final attempt at blocking the entrance to Port Arthur, this time with eight old transports. The attempt also failed, but Togo proclaimed it to be a success, thus clearing the way for the Japanese Second Army to land in Manchuria. Although Port Arthur was as good as blocked, due to the lack of initiative by Makarov's successors, Japanese losses began to mount, largely due to Russian mines.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Connaughton, Richard. 2003. Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36657-9

- Kowner, Rotem. 2006. Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5

- Nish, Ian. 1985. The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49114-2

- Sedwick, F.R. 1909. The Russo-Japanese War. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.