Battle of Smolensk (1943)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

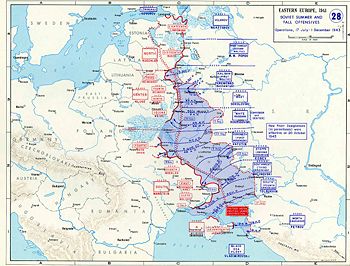

Known in German history as the second Battle of Smolensk (August 7, 1943–October 2, 1943), this was a Soviet Smolensk Offensive operation (Смоленская наступательная операция)(Operation Suvorov, операция "Суворов"), conducted by the Red Army as part of the Summer-Autumn Campaign of 1943 (Летне-осенняя кампания 1943) (July 1–December 31) in the Western USSR. Staged almost simultaneously with the Donbass Offensive Operation (Донбасская наступательная операция) (August 13–September 22) also know in German history as the Battle of the Dnieper, the offensive lasted 2 months and was led by Generals Andrei Yeremenko commanding the Kalinin Front and Vasily Sokolovsky commanding the Western Front. Its goal was to clear Wehrmacht presence from Smolensk and Bryansk regions. Smolensk had been under German occupation since the first Battle of Smolensk in 1941.

Despite an impressive German defense, the Red Army was able to stage several breakthroughs, liberating several major cities including Smolensk and Roslavl. As a result of this operation, the Red Army was able to commence planning for the liberation of Belorussia. However, the overall advance was quite modest and slow in the face of heavy German resistance, and the operation was therefore accomplished in three stages: August 7–20, August 21–September 6, and September 7–October 2.

Although playing a major military role in its own right, the Smolensk Operation was also important for its effect on the Battle of the Dnieper. It has been estimated that as many as fifty-five German divisions were committed to counter the Smolensk Operation—divisions which would have been critical to prevent Soviet troops from crossing the Dnieper in the south. In the course of the operation, the Red Army also definitively drove back German forces from the Smolensk land bridge, historically the most important approach for a western attack on Moscow. Smolensk was part of the turning point in the war as the initial Nazi military victories began to be reversed and the problems of supply lines, inclement weather, and inhospitable conditions began to take its toll of the German army.

Strategic context

By the end of the Battle of Kursk in July 1943, the Wehrmacht had lost all hope of regaining the initiative on the Eastern Front. Losses were considerable and the whole army was less effective than before, as many of its experienced soldiers had fallen during the previous two years of fighting. This left the Wehrmacht capable of only reacting to Soviet moves.

On the Soviet side, Stalin was determined to pursue the liberation of occupied territories from German control, a course of action that had started at the end of 1942, with Operation Uranus, which led to the liberation of Stalingrad. The Battle of the Dnieper was to achieve the liberation of the Ukraine and push the southern part of the front towards the west. However, in order to weaken the German defenses even further, the Smolensk operation was staged simultaneously, in a move that would also draw German reserves north, thereby weakening the German defense on the southern part of the front. Both operations were a part of the same strategic offensive plan, aimed at recovering as much Soviet territory from German control as possible

Thirty years later, Marshal Vasilevsky (Chief of the General Staff in 1943) wrote in his memoirs:

This plan, enormous both in regard of its daring and of forces committed to it, was executed through several operations: the Smolensk operation, …the Donbass [Operation], the left-bank Ukraine operation…[4]

Geography

The territory on which the offensive was staged was a slightly hilly plain covered with ravines and possessing significant areas of swamps and forests that restricted military movement. Its most important hills reach heights of 250 to 270 meters (750–800 ft), sometimes even more, allowing for improved artillery defense. In 1943, the area was for the most part covered with pine and mixed forests and thick bushes.[5]

Numerous rivers also pass through the area, the most important of which are the Donets Basin, Western Dvina, Dnieper, Desna, Volost, and Ugra rivers. None of these rivers were especially wide at 10 to 120 meters (30 to 360 ft) respectively, nor deep at 40 to 250 cm (1 to 8 ft) respectively; but the surrounding wide, swamp-like areas proved difficult to cross, especially for mechanized troops. Moreover, like many south-flowing rivers in Europe, the Dnieper's western bank, which was held by German troops, was higher and steeper than the eastern. There were very few available bridges or ferries.[6]

Transport infrastructure

For the Soviet troops, the offensive was further complicated by a lack of adequate transport infrastructure in the area in which the offensive was to be staged. The road network was not well developed, and paved roads were rare. After rainfall, which was quite common during the Russian summer, most of them were turned into mud (a phenomenon known as rasputitsa), greatly slowing down any advance of mechanized troops, and raising logistical issues as well. As for railroads, the only major railroad axis available for Soviet troops was the Rzhev-Vyazma-Kirov line.

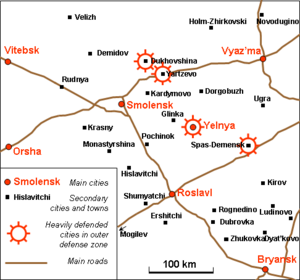

On the other hand, the Wehrmacht controlled a much wider network of roads and railroads, centered on Smolensk and Roslavl. These two cities were important logistical centers, allowing quick supply and reinforcements for German troops. By far the most important railroads for German troops were the Smolensk-Bryansk axis and the Nevel-Orsha-Mogilev axis, linking German western troops with troops concentrated around Oryol. However, as part of the Soviet planning the German railroad communications were attacked by the partisans during the conduct of Operation Concert, one of the largest railroad sabotage operations of the Second World War.

Opposing forces

Soviet offensive sector

As of July 1943, the shape of the Soviet front line on this part of the Eastern Front was described as a concave with a re-entrant centered around Oryol, offering them the opportunity to attack Wehrmacht defensive lines, which became exposed to flank attacks from the north.

Therefore, the offensive promised to be quite difficult for Soviet troops of the Kalinin and Western Fronts who were predominantly tasked with the operation.

The Kalinin Front had assigned to the operation the 10th Guards Аrmy, 5th Army , 10th Army, 21st Army, 33rd Army, 49th Army, 68th Аrmy, 1st Air Army, 2nd Guards Tank Corps, 5th Mechanized Corps, and 6th Guards Cavalry Corps.

The Western Front would have for the operation the 4th Shock Army, 39th Army, 43rd Army, 3rd Air Army, and 31st Army.

German defenses

As a result of the shape of the front, a significant number of divisions of Army Group Center were kept on this part of the front because of a (quite legitimate) fear of a major offensive in this sector.

For instance, at the end of July 1943, a German staff briefing stated:

On the front… held by the Army Group Center many signs show a continuous preparation to a yet limited offensive (Roslavl, Smolensk, Vitebsk) and of a maneuver of immobilization of the Army Group Center…[7]

The front had been more or less stable for four to five months (and up to 18 months in several places) before the battle, and possessed geographical features favorable for a strong defensive setup. Thus, German forces had time to build extensive defensive positions, numbering as much as five or six defensive lines in some places, for a total depth extending from 100 to 130 kilometers (60–80 mi).[8]

The first (tactical or outer) defensive zone included the first (main) and the second defense lines, for a total depth varying between 12 and 15 kilometers (7–9 mi), and located, whenever possible, on elevated ground. The main defense line, 5 kilometers deep, possessed three sets of trenches and firing points, linked by an extensive communication network. The density of firing points reached 6 or 7 per kilometers (0.6 mi) of front line. In some places, where heavy tank attacks were feared, the third set of trenches was in fact a solid antitank moat with a steep western side integrating artillery and machine guns emplacements. The forward edge of the battle area was protected by three lines of barbed wire and a solid wall of minefields.[9]

The second defense zone, located about 10 kilometers (6 mi) behind the outer defense zone and covering the most important directions, was composed of a set of firing points connected with trenches. It was protected with barbed wire, and also with minefields in some places where heavy tank offensives were anticipated. Between the outer and the second defense zones, a set of small firing points and garrisons was also created in order to slow down a Soviet advance should the Red Army break through the outer defense zone. Behind the second zone, heavy guns were positioned.

Finally, deep behind the front line, three or four more defense lines were located, whenever possible, on the western shore of a river. For instance, important defense lines were set up on the western side of the Dnieper and Desna. Additionally, the main urban centers located on the defense line (such as Yelnya, Dukhovshchina, and Spas-Demensk), were reinforced and fortified, preparing them for a potentially long fight. Roads were mined and covered with antitank devices and firing points were installed in the most important and tallest buildings.

First stage (August 7–August 20)

Main breakthrough

After a day of probing, the goal of which was to determine whether German troops would choose to withdraw or not from the first set of trenches, the offensive started on August 7, 1943, at 06:30 a.m. (with a preliminary bombardment starting at 04:40 a.m.) with a breakthrough towards Roslavl. Three armies (apparently under the control of Soviet Western Front) were committed to this offensive: The 5th Army (Soviet Union), the 10th Guards Army, and the 33rd Army.

However, the attack quickly encountered heavy opposition and stalled. German troops attempted numerous counterattacks from their well-prepared defense positions, supported by tanks, assault guns, and the fire of heavy guns and mortars. As Konstantin Rokossovsky recalls, "we literally had to tear ourselves through German lines, one by one."[10] On the first day, the Soviet troops advanced only 4 kilometers (2.5 mi),[11] with all available troops (including artillery, communications men, and engineers) committed to battle.[12]

Despite violent Soviet attacks, it quickly became obvious that the three armies would not be able to get through the German lines. Therefore, it was decided to commit the 68th Army, kept in reserve, to the battle. On the German side, three additional divisions (2nd Panzer Division, 36th Infantry Division, and 56th Infantry Division) were sent to the front from the Oryol sector to try to halt the Soviet advance.

The following day, the attack resumed, with another attempt at a simultaneous breakthrough taking place further north, towards Yartzevo. Both attacks were stopped in their tracks by heavy German resistance. In the following five days, Soviet troops slowly made their way through German defenses, repelling heavy counterattacks and sustaining heavy losses. By feeding reserve troops to battle, the Red Army managed to advance to a depth varying from 15 to 25 kilometers (10–15 mi) by August 11.[13]

Subsequent attacks by the armored and cavalry forces of the 6th Guards Cavalry Corps had no further effect and resulted in heavy casualties because of strong German defenses, leading to a stalemate.

Spas-Demensk offensive

During the Spas-Demyansk offensive operation (Спас-Деменская наступательная операция) in the region of Spas-Demensk, things went a little better for the 10th Army. In this area, Wehrmacht had fewer troops and only limited reserves, enabling the 10th Army to break through German lines and advance 10 kilometers in two days.

However, the 5th Mechanized Corps,[14] relocated from Kirov and committed to battle in order to exploit the breakthrough, failed in its mission, mainly because a poorly organized anti-aircraft defense enabled Luftwaffe dive bombers to attack its light Valentine tanks with a certain degree of impunity. The corps sustained heavy losses and had to pull away from combat. Eventually, Soviet troops advanced a further 25 kilometers (15 mi) as of August 13, liberating Spas-Demensk.[15]

Dukhovshchina offensive

As ordered by the Stavka (the Soviet Armed Forces Command), the Dukhovshchina-Demidov offensive operation (Духовщинско-Демидовская наступательная операция) near Dukhovshchina started almost a week later, on August 13. However, as on other parts of the front, the 39th Army and the 43rd Army encountered very serious opposition. During the first day alone, Wehrmacht troops attempted 24 regimental-sized counterattacks, supported by tanks, assault guns, and aviation.[16]

During the next five days, Soviet troops managed to advance only 6 to 7 kilometers (3 to 4 mi), and although they inflicted heavy casualties on Wehrmacht troops, their own losses were also heavy.[17]

Causes of the stalemate

By mid-August, Soviet operations all along the Smolensk front stabilized. The resulting stalemate, while not a defeat per se, was stinging for Soviet commanders, who provided several explanations for their failure to press forward. Deputy Chief of General Staff General A. I. Antonov reported "We have to deal both with forests and swamps and with increasing resistance of enemy troops reinforced by divisions arriving from Bryansk region"[18] while Marshal Nikolai Voronov, formerly a Stavka member, analyzed the stalemate in his memoirs, publishing what he saw as the eight primary causes:[19]

- The Wehrmacht OHK command knew about the operation and was prepared for it.

- Wehrmacht defense lines were exceptionally well prepared (firing points reinforced by trenches, barbed wire, minefields etc.)

- Several Red Army rifle divisions were insufficiently prepared to perform an assault of a multi-lined defense setup. This was especially true for reserve divisions, whose training was not always properly supervised.

- There were not enough tanks committed to battle, forcing Red Army commanders to rely on artillery, mortars, and infantry to break through Wehrmacht lines. Moreover, numerous counterattacks and an abundance of minefields slowed down the infantry's progress.

- The interaction between regiments and divisions was far from perfect. There were unexpected pauses during the attack and a strong will of some regiments to "hide" from the attack and expose another regiment.

- Many Red Army commanders were too impressed by Wehrmacht counterattacks and failed to act properly, even if their own troops outnumbered those of the Wehrmacht.

- The infantry were not using their own weapons (such as their own heavy guns and portable mortars) well enough. They relied too much on artillery.

- The fact that the offensive was postponed from August 3 to August 7 gave German troops more time to increase their readiness.

With all these factors considered, Voronov demanded that the 4th Tank Army and the 8th Artillery Corps be transferred from the Bryansk Front and instead committed to support the attack near Smolensk.[20]

The stalemate was far from what had been desired by the Stavka, but it had at least one merit: It tied down as much as 40 percent of all Wehrmacht divisions on the Eastern Front near Smolensk, making the task for troops fighting in the south and near Kursk much easier.[21] The Stavka planned to resume the offensive on August 21, but decided to postpone it slightly to give Soviet units time to resupply and reinforce.[22]

Second stage (August 21–September 6)

By mid-August, the situation on the Eastern Front had changed as the Red Army started a general offensive, beginning with the Belgorod-Kharkov offensive operation (Белгородско-Харьковская наступательная операция)(Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev операция "Румянцев") and the Orlov offensive operation (Орловская наступательная операция) (Operation Polkovodets Kutuzov]] операция "Кутузов") known in German history as the Kursk, and continuing with the Wehrmacht's defensive Battle of the Dnieper line in the North Ukraine. Nevertheless, the Wehrmacht command was still reinforcing its troops around Smolensk and Roslavl, withdrawing several divisions from the Oryol region. As a result, the two Soviet counteroffensives that followed the Kursk defensive operation (Курская оборонительная операция) proceeded relatively easily for the Red Army around Oryol, creating a large salient south of Smolensk and Bryansk.

In this situation, the former attack axis, directed southwest towards Roslavl and Bryansk, became useless. The Stavka decided instead to shift the attack axis west to Yelnya and Smolensk.[23]

Yelnya offensive

The Yelnya-Dorogobuzh offensive operation (Ельнинско-Дорогобужская наступательная операция) was considered the "key" to Smolensk, and therefore Wehrmacht troops created a massive fortified defense position around the city. Swampy areas on the Desna and Ugra rivers were mined and heavy guns set up on hills overlooking the city.

Aware of the Wehrmacht preparations, during the week from August 20 to August 27, the Soviet armies were reinforced with tanks and artillery.

The offensive finally commenced on August 28, by the 10th Guards Army, 21st Army and the 33rd Army ), supported by three Tank, a Mechanized corps and the 1st Air Army. These four armies were covering a front of only 36 kilometers (22 mi), creating a very high concentration of troops. However, the troops lacked fuel and supplies, with enough to last only one or two weeks.[24]

After an intense shelling that lasted 90 minutes, Soviet troops moved forward. The artillery bombardment as well as ground attack aircraft significantly damaged the Wehrmacht lines, allowing the Red Army to execute a breakthrough on a 25 kilometer (15 mi) sector front and advance 6 to 8 kilometers (4–5 mi) by the end of the day. The following day, August 29, Red Army rifle divisions advanced further, creating a salient 30 kilometers (19 mi) wide and 12 to 15 kilometers (7–9 mi) deep.[25]

In order to exploit the breakthrough, the 2nd Guards Tank Corps was thrown into the battle. In one day, its troops advanced by 30 kilometers (19 mi) and reached the outskirts of Yelnya. Leaving Wehrmacht troops no time to regroup their forces, Red Army troops attacked the city and started to form an encirclement. On August 30, Wehrmacht forces were forced to abandon Yelnya, sustaining heavy casualties. This commenced a full-scale retreat by Wehrmacht troops from the area. By September 3, Soviet forces reached the eastern shore of the Dniepr.

Bryansk maneuver

Near Bryansk, things went equally well, despite heavy German resistance. However, an identified weakness changed all the previous plans. A surprisingly easy capture of several hills commanding the Dubrovka region north of Bryansk, with numerous German soldiers captured in total absence of battle readiness, came to the attention of General Markian Popov, commander of the Bryansk Front from June to October 1943.[26] This meant that the Soviet offensive was probably not expected along that particular axis.

Therefore, the boundary between the First Belorussian Front and the Western Front was shifted south, and two "new" armies executed a single-pincer movement to Dubrovka and around Bryansk, forcing German forces to withdraw.[27]

By September 6, the offensive slowed down almost to a halt on the entire front, with Soviet troops advancing only 2 kilometers (1 mi) each day. On the right flank, heavy fighting broke out in the woods near Yartzevo. On the center, advancing Soviet troops hit the Dnieper defense line. On the left flank, Soviet rifle divisions were slowed as they entered forests southwest of Yelnya. Moreover, Soviet divisions were tired and depleted, at less than 60 percent nominal strength. On September 7, the offensive was stopped, and the second stage of the Smolensk operation was over.[28]

Third stage (September 7–October 2)

In the week from September 7 to September 14, Soviet troops were once again reinforced and were preparing for another offensive. The next objectives set by the Stavka were the major cities of Smolensk, Vitebsk and Orsha. The operation resumed on September 14, with the Smolensk-Roslavl offensive operation (Смоленско-Рославльская наступательная операция), involving the left flank of the Kalinin Front and the Western Front. After a preliminary artillery bombardment, Soviet troops attempted to break through the Wehrmacht lines.

On the Kalinin Front’s attack sector, the Red Army created a salient 30 kilometers (19 mi) wide and 3 to 13 kilometers (2–8 mi) deep by the end of the day. After four days of battle, Soviet rifle divisions captured Dukhovshchina, another "key" to Smolensk.[29]

On the Western Front's attack sector, where the offensive started one day later, the breakthrough was also promising, with a developing salient 20 kilometers (12 mi) large and 10 kilometers (6 mi) deep. The same day, Yartzevo, an important railroad hub near Smolensk, was liberated by Soviet troops. On the Western Front's left flank, Soviet rifle divisions reached Desna and conducted an assault river crossing, creating several bridgeheads on its western shore.

As the result, the Wehrmacht defense line protecting Smolensk was overrun, exposing the troops defending the city to envelopment. General Kurt von Tippelskirch, Chief of Staff of the German 4th Army during the Smolensk operation and later commander of the 4th Army, wrote that:

"The forces of the Soviet Western Front struck the left wing of Army Group Center from the Dorogobuzh-Yelnya line with the aim of achieving a breakthrough in the direction of Smolensk. It became clear that the salient—projecting far to the east—in which the 9th Army was positioned could no longer be held."[30]

By September 19, Soviet troops had created a 250 kilometers (150 mi) large and 40 kilometers (25 mi) wide gap in Wehrmacht lines. The following day, Stavka ordered the Western Front troops to reach Smolensk before September 27, then to proceed towards Orsha and Mogilev. Kalinin front was ordered to capture Vitebsk before October 10.

On September 25, after a assault-crossing of the northern Dnieper and street fighting that lasted all night, Soviet troops completed the liberation of Smolensk. The same day another important city of Roslavl was recaptured. By September 30, the Soviet offensive force were tired and depleted, and became bogged down outside Vitebsk, Orsha, and Mogilev, which were still held by Wehrmacht troops, and on October 2, the Smolensk operation was concluded. A limited follow-on was made to successfully capture Nevel after two days of street fighting.

Overall, Soviet troops advanced 100 to 180 kilometers (60–110 mi) during almost 20 days of this third part of the offensive.[31]

The Battle of Lenino (in the Byelorussian SSR) occurred in the same general area on October 12/13, 1943.

Aftermath

The Smolensk operation was a decisive Soviet victory and a stinging defeat for the Wehrmacht. Although quite modest compared to later offensive operations (not more than 200–250 kilometers or 120–150 miles were gained in depth[32]), the Soviet advance during this operation was important from several points of view.

Firstly, German troops were definitively driven back from the Moscow approaches. This strategic threat, which had been the Stavka's biggest source of worry since 1941, was finally removed.

Secondly, German defense rings, on which German troops planned to rely, were almost completely overrun. Quite a few remained, but it was obvious that they would not last. An essay written after the war by several Wehrmacht officers stated that:

Although the vigorous actions of their command and troops allowed the Germans to create a continuous front, there was no doubt that the poor condition of the troops, the complete lack of reserves, and the unavoidable lengthening of individual units' lines concealed the danger that the next major Soviet attack would cause this patchwork front—constructed with such difficulty—to collapse.[33]

Thirdly, as outlined above, the Smolensk Operation was an important "helper" for the Battle of the Dnieper, locking between 40 and 55 divisions near Smolensk and preventing their relocation to the southern front.

Finally, a once-united German front was now separated by the huge and impassable Pripet marshes, cutting Army Group South off from its northern counterparts, thus greatly reducing the Wehrmacht's abilities to shift troops and supplies from one sector of the front to the other.[34]

For the first time, Soviet troops entered territories which had been occupied for a long time by German soldiers, and discovered war crimes committed by the SS, Einsatzgruppen, and Wehrmacht troops. In the areas liberated during the Smolensk operation (occupied for almost two years), almost all industry and agriculture was gone. In Smolensk oblast itself, almost 80 percent of urban and 50 percent of rural living space had been destroyed, along with numerous factories and plants.[35]

After the Smolensk offensive, the central part of the Soviet-German front stabilized again for many months until late June 1944, while the major fighting shifted to the south for the Dnieper line and the territory of the Ukraine. Only during January 1944, would the front move again in the north, when German forces were driven back from Leningrad, completely lifting the siege which had lasted for 900 days. Finally, Operation Bagration in summer 1944, allowed the Red Army to clear almost all the remaining territory of the USSR of Wehrmacht troops, ending German occupation and shifting the war into Poland and Germany.

Notes

- ↑ A.A. Grechko et al., History of Second World War (Moscow, 1973), p.241.

- ↑ V.A. Zolotarev, et al., Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 (Collection of Essays) (Moscow, 1998), p. 473.

- ↑ Nikolai Shefov, Russian Fights (Moscow: Lib. Military History, 2002).

- ↑ Marshal A.M. Vasilevsky, The Matter of my Whole Life (Moscow: Politizdat, 1973), p. 327.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, Smolensk offensive operation, 1943 (Moscow: Mil. Lib., 1975), p. 15.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 16

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 12.

- ↑ Marshal N.N. Voronov, On Military Duty (Moscow: Lib. Milit. Ed., 1963), p. 382.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 12.

- ↑ K. Rokossovsky, Soldier's Duty (Moscow: Politizdat, 1988), p. 218.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 81–82.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p.84.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 84–88.

- ↑ John Erickson, Road to Berlin, (1982), p.130

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 92–94

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 94–95.

- ↑ A.A. Grechko et al., History of Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945 (Moscow, 1963), p. 361.

- ↑ G.K. Zhukov, Memoirs (Moscow, Ed. APN, 1971), p. 485.

- ↑ Voronov, p. 387—388.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 101.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, Operations of Soviet Armed Forces during the Great Patriotic War 1941—1945 (Moscow: Voenizdat, 1958).

- ↑ Marshal A.I. Yeremenko, Years of Retribution (Moscow: Science, 1969), p. 51—55.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 104.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 105

- ↑ V.P.Istomin, p.110.

- ↑ Voenno-istoricheskiy zhurnal (Military history journal) 1969(10): 31

- ↑ Voenno-istoricheskiy zhurnal, p. 32.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 122–123.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 131.

- ↑ Kurt Tippelskirch, History of Second World War (Moscow, 1957), p. 320–321.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 134–136.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 5.

- ↑ World War 1939–1945 (collection of essays) (Moscow: Ed. Foreign Lit., 1957), p. 216–217.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 163.

- ↑ V.P. Istomin, p. 15.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Glantz, David M., and Jonathan M. House. When Titans Clashed, Modern War Studies. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1995. ISBN 9780700607174

- Grechko, A.A., et al. History of Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945. Moscow, 1963.

- Grechko, A.A., et al. History of Second World War. Moscow, 1973.

- Istomin, V.P. Operations of Soviet Armed Forces During the Great Patriotic War 1941—1945. Moscow: Voenizdat, 1958.

- Istomin, V.P. Smolensk Offensive Operation, 1943. Moscow: Mil. Lib., 1975.

- Rokossovsky, K. Soldier's Duty. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1985.

- Shefov, Nikolai. Russian Fights. Moscow: Lib. Military History, 2002.

- Tippelskirch, Kurt. History of Second World War. Moscow, 1957.

- Vasilevsky, A.M. The Matter of my Whole Life. Moscow: Politizdat, 1973.

- Voenno-istoricheskiy zhurnal (Military history journal). 1969 (10): 31, 32

- Voronov, N.N. On Military Duty. Moscow: Lib. Milit. Ed., 1963.

- World War 1939–1945 (collection of essays). Moscow: Ed. Foreign Lit., 1957.

- Yeremenko, A.I. Years of Retribution. Moscow: Science, 1969.

- Zhukov, G.K. Memoirs. Moscow: Ed. APN, 1971.

- Zolotarev, V.A. et al. Great Patriotic War 1941–1945. Moscow, 1998.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.