Binomial nomenclature

In biology, binomial nomenclature is the formal system of naming species whereby each species is indicated by a two-part name, a capitalized genus name followed by a lowercase specific epithet or specific name, with both names italicized (or underlined if handwritten, not typeset) and both in (modern scientific) Latin. For example, the lion is designated as Panthera leo, the tiger as Panthera tigris, the snowshoe hare as Lepus americanus, the blue whale as Balaenoptera musculus, and the giant sequoia as Sequoiadendron giganteum. This naming system is called variously binominal nomenclature (particularly in zoological circles), binary nomenclature (particularly in botanical circles), or the binomial classification system.

Species' names formulated by the convention of binomial nomenclature are popularly known as the "Latin name" of the species, although this terminology is frowned upon by biologists and philologists, who prefer the phrase scientific name. The binomial classification system is used for all known species, extant (living) or extinct.

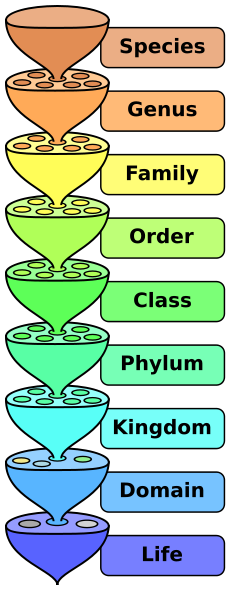

The species is the lowest taxonomic rank of organism in the binomial classification system.

Naming the diverse organisms in nature is an ancient act, even referenced in the first book of the Bible: "The Lord God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name. The man gave names to all cattle, and to the birds of the air, and to every beast of the field" (Genesis 2:19-20).

Given the multitude of diverse languages and cultures, however, diverse common names are given to the same species, depending on the location and local language. For example, the "moose" of North America, Alces alces, is the "elk" of Anglophone Europe, while "elk" in North America refers to another species, Cervus canadensis. The use of binomial nomenclature allows the same name to be used all over the world, in all languages, avoiding difficulties of translation or regionally used common names.

Rules for binomial nomenclature

General rules

Although the fine details of binomial nomenclature will differ, certain aspects are universally adopted:

- The scientific name of each species is formed by the combination of two words—as signified equally by "binomial," "binominal," and "binary"—and the two words are in a modern form of Latin:

- Species names are usually typeset in italics; for example, Homo sapiens. Generally, the binomial should be printed in a type-face (font) different from that used in the normal text; for example, "Several more Homo sapiens were discovered." When handwritten, species names should be underlined; for example, Homo sapiens. Each name should be underlined individually.

- The genus name is always written with an initial capital letter.

- In zoology, the specific name is never written with an initial capital.

- For example, the tiger species is Panthera tigris

- In botany, an earlier tradition of capitalizing the specific epithet when it was based on the name of a person or place has been largely discontinued, so the specific epithet is written usually all in lower case.

- For example, Narcissus papyraceus

- There are several terms for this two-part species name; these include binomen (plural binomina), binomial, binomial name, binominal, binominal name, and species name.

Higher and lower taxa

- All taxa at ranks above species, such as order or phylum, have a name composed of one word only, a "uninominal name."

- The first level subdivisions within a species, termed subspecies, are each given a name with three parts: the two forming the species name plus a third part (the subspecific name) which identifies the subspecies within the species. This is called trinomial nomenclature, and is written differently in zoology and botany (Bisby 1994). For example:

- Two of the subspecies of olive-backed pipit (a bird) are Anthus hodgsoni berezowskii and Anthus hodgsoni hodgsoni.

- The Bengal Tiger is Panthera tigris tigris and the Siberian Tiger is Panthera tigris altaica.

- The tree European black elder is Sambucus nigra subsp. nigra and the American black elder is Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis.

Several species or indeterminate species

- The scientific name should generally be written in full. The exception to this is when several species from the same genus are being listed or discussed in the same paper or report; in that case the genus is written in full when it is first used, but may then be abbreviated to an initial (and period) for successive species names. For example, in a list of members of the genus Canis, when not first in the list Canis lupus becomes C. lupus. In rare cases, this abbreviated form has spread to more general use; for example, the bacterium Escherichia coli is often referred to as just E. coli, and Tyrannosaurus rex is perhaps even better known simply as T. rex, these two both often appearing even where they are not part of any list of species of the same genus.

- The abbreviation "sp." is used when the actual specific name cannot or need not be specified. The abbreviation "spp." (plural) indicates "several species." These are not italicized (or underlined).

- For example: "Canis sp.," meaning "one species of the genus Canis."

- Easily confused with the foregoing usage is the abbreviation "ssp." (zoology) or "subsp." (botany) indicating an unspecified subspecies. (Likewsie, "sspp." or "subspp." indicates "a number of subspecies".)

- The abbreviation "cf." is used when the identification is not confirmed.

- For example Corvus cf. splendens indicates "a bird similar to the house crow (Corvus splendens) but not certainly identified as this species."

Additional standards

- In scholarly texts, the main entry for the binomial is followed by the abbreviated (in botany) or full (in zoology) surname of the scientist who first published the classification. If the species was assigned in the description to a different genus from that to which it is assigned today, the abbreviation or name of the describer and the description date is set in parentheses.

- For example: Amaranthus retroflexus L. or Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758)—the latter was originally described as member of the genus Fringilla, hence the parentheses.

- When used with a common name, the scientific name often follows in parentheses.

- For example, "The house sparrow (Passer domesticus) is decreasing in Europe."

Derivation of names

The genus name and specific descriptor may come from any source. Often they are ordinary New Latin words, but they may also come from Ancient Greek, from a place, from a person (preferably a naturalist), a name from the local language, and so forth. In fact, taxonomists come up with specific descriptors from a variety of sources, including inside-jokes and puns.

However, names are always treated grammatically as if they were a Latin phrase. There is a list of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names.

Family names are often derived from a common genus within the family.

The genus name must be unique inside each kingdom. It is normally a noun in its Latin grammar.

The specific descriptor is also a Latin word but it can be grammatically any of various forms, including these:

- another noun nominative form in apposition with the genus; the words do not necessarily agree in gender. For example, the lion Panthera leo.

- a noun genitive form made up from a person's surname, as in the Tibetan antelope Pantholops hodgsonii, the shrub Magnolia hodgsonii, or the olive-backed pipit Anthus hodgsoni. Here, the person named is not necessarily (if ever) the person who names the species; for example Anthus hodgsoni was named by Charles Wallace Richmond, not by Hodgson.

- a noun genitive form made up from a place name, as with Latimeria chalumnae ("of Chalumna").

- the common noun genitive form (singular or plural) as in the bacterium Escherichia coli. This is common in parasites, as in Xenos vesparum where vesparum simply means "of the wasps."

- an ordinary Latin or New Latin adjective, as in the house sparrow Passer domesticus where domesticus (= "domestic") simply means "associated with the house" (or "… with houses").

Specific descriptors are commonly reused (as is shown by examples of hodgsonii above).

Value of binomial nomenclature

The value of the binomial nomenclature system derives primarily from its economy, its widespread use, and the stability of names it generally favors:

- Every species can be unambiguously identified with just two words.

- The same name can be used all over the world, in all languages, avoiding difficulties of translation.

- Although such stability as exists is far from absolute, the procedures associated with establishing binomial nomenclature tend to favor stability. For example, when species are transferred between genera (as not uncommonly happens as a result of new knowledge), if possible the species descriptor is kept the same, although the genus name has changed. Similarly if what were previously thought to be distinct species are demoted from species to a lower rank, former species names may be retained as infraspecific descriptors.

Despite the rules favoring stability and uniqueness, in practice a single species may have several scientific names in circulation, depending largely on taxonomic point of view. For example, the clove is typically designated as Syzygium aromaticum, but is also known by the synonyms Eugenia aromaticum and Eugenia caryophyllata.

History

The adoption of a system of binomial nomenclature is due to Swedish botanist and physician Carolus Linnaeus (1707 – 1778) who attempted to describe the entire known natural world and gave every species (mineral, vegetable, or animal) a two-part name.

In 1735, Linnaeus published Systema Naturae. By the time it reached its tenth edition in 1758, the Systema Naturae included classifications of 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. In it, the unwieldy names mostly used at the time, such as "Physalis amno ramosissime ramis angulosis glabris foliis dentoserratis," were supplemented with concise and now familiar "binomials," composed of the generic name, followed by a specific epithet, such as Physalis angulata. These binomials could serve as a label to refer to the species. Although the system, now known as binomial nomenclature, was developed by the Bauhin brothers (Gaspard Bauhin and Johann Bauhin) almost two hundred years earlier, Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently, and may be said to have popularized it within the scientific community. Before Linnaeus, hardly anybody used binomial nomenclature. After Linnaeus, almost everybody did.

Codes of nomenclature

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, it became ever more apparent that a body of rules was necessary to govern scientific names. In the course of time these became Nomenclature Codes governing the naming of animals (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, ICZN), plants (including fungi and cyanobacteria) (International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, ICBN), bacteria (International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria, ICNB), and viruses (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, ICTV). These Codes differ.

- For example, the ICBN, the plant Code, does not allow tautonyms (where the name of the genus and the specific epithet are identical), whereas the ICZNm the animal Code, does allow tautonyms.

- The starting points, the time from which these Codes are in effect (retroactively), vary from group to group. In botany, the starting point will often be in 1753 (the year Carolus Linnaeus first published Species Plantarum), while in zoology the year is 1758. Bacteriology started anew, with a starting point on January 1, 1980 (Sneath 2003).

A BioCode has been suggested to replace several codes, although implementation is not in sight. There also is debate concerning development of a PhyloCode to name clades of phylogenetic trees, rather than taxa. Proponents of the PhyloCode use the name "Linnaean Codes" for the joint existing Codes and "Linnaean taxonomy" for the scientific classification that uses these existing Codes.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bisby, F. A. 2994. Plant names in botanical databases Plant Taxonomic Database Standards No. 3, Version 1.00. Published for the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences (TDWG) by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- International Botanical Congress (16th: 1999: St. Louis, Mo.), W. Greuter, and J. McNeill. 2000. International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (Saint Louis Code) Adopted by the Sixteenth International Botanical Congress, St. Louis, Missouri, July-August 1999. Prepared and Edited by W. Greuter, chairman, J. McNeill, et al.. Konigstein, Germany: Koeltz Scientific Books. ISBN 3904144227.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) and W. D. L. Ride. 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, 4th edition. London: International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, c/o Natural History Museum. ISBN 0853010064.

- Sneath, P. H. A. 2003. A short history of the Bacteriological Code International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes (ICSP).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.