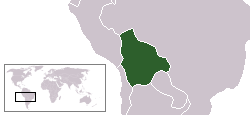

Bolivia

| Plurinational State of Bolivia Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia (Spanish) Bulivya Mamallaqta (Quechua) Wuliwya Suyu (Aymara) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "¡La union es la fuerza!"  "Unity is (the) strength!" |

||||||

| Anthem: Bolivianos, el hado propicio  "Bolivians, a most favorable destiny" |

||||||

| Capital | Sucre (constitutional capital) | |||||

| Largest city | Santa Cruz de la Sierra | |||||

| Official language(s) | Spanish Quechua Aymara and 34 other native languages |

|||||

| Ethnic groups  | 68% Mestizo 20% Indigenous Bolivians 5% White 1% Black 4% Other 2% Unspecified |

|||||

| Demonym | Bolivian | |||||

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic | |||||

|  -  | President | Luis Arce | ||||

|  -  | Vice President | David Choquehuanca | ||||

| Independence | from Spain  | |||||

|  -  | Declared | 6 August 1825  | ||||

|  -  | Recognized | 21 July 1847  | ||||

| Area | ||||||

|  -  | Total | 1,098,581 km2 (28th) 424,163 sq mi  |

||||

|  -  | Water (%) | 1.29 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

|  -  | 2023 estimate | 12,186,079[1] (79th) | ||||

|  -  | Density | 10.4/km2 (224th) 26,9/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | |||||

|  -  | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | |||||

|  -  | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2021) | 40.9[3]  | |||||

| HDI (2022) | 0.698[4] (118th) | |||||

| Currency | Boliviano (BOB) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC-4) | |||||

| Drives on the | Right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .bo | |||||

| Calling code | +591 | |||||

The Republic of Bolivia (or Bulibiya in the Quechua language; Wuliwya in Aymara) is a landlocked country in central South America. It is bordered by Brazil on the north and east, Paraguay and Argentina on the south, and Chile and Peru on the west. Although only one-third of the country is located in the Andean mountain range, its largest city and principal economic centers are in the highlands. Bolivia was part of the Inca Empire, and today 60 percent of its people are of unmixed native ancestry and directly descended from the Aymaras and the Incas.

Bolivia’s vast mineral wealth has been its curse as well as its blessing. Spain built its empire in great part upon the silver that was extracted from Bolivia's mines. It is said that the Spanish extracted enough silver from Bolivia to build a bridge of silver from South America to Spain. The tragedy is that this wealth was created upon the blood, sweat, and tears of Bolivia’s Indians. In other parts of the New World the Spanish simply eliminated the Indian population. In Bolivia, the Spanish employed the Indians to work the mines. Husbands, fathers, and sons were sent to the mines as forced labor, often to never again see their families. It was not uncommon for hopelessness, melancholia, and depression to lead miners to suicide.

The racial and social apartheid that arose from Spanish colonialism has continued to the modern era. Before the revolution of 1952, native Bolivians were not permitted even to enter the principal plaza of La Paz, which contains the presidential palace and the congress. Many indigenous Bolivians today still seek to ‚Äúpass‚ÄĚ as mixed blood mestizos, whose social status is regarded as somewhat higher.

Geography

In Bolivia, the Andes Mountains divide into two ranges, the Eastern and Western Cordilleras, with a high plateau in the center. This cold, arid, windswept plateau is virtually treeless and barren, and yet is home to about 40 percent of the people, including those who live in the largest city, La Paz. This area, known as Altiplano, is rich in mineral resources, and today remains a major producer of tin and gold. After silver was discovered in the mountains near Potosi in 1545, Spaniards poured into Bolivia by the thousands, building a mineral-based economy that persists to this day. Bolivia's silver became an important source of wealth for Spain. The Spaniards employed thousands of Indians in the mines under often cruel and brutal conditions.

Today Bolivia is a landlocked nation, having lost its outlet to the sea following a disastrous war with Chile in 1883. However, it does have access to the Atlantic via the Paraguay River. Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world, is located on the border between Bolivia and Peru. In the west lies the Salar de Uyuni, the world's largest salt flats.

La Paz, the country’s largest city, principal financial center, and seat of the executive and legislative branches of government, lies in an altiplano canyon riverbed. At 3,810 meters (12,500 feet) above sea level, La Paz is the world's highest capital. The snow-capped peak of Mount Illimani (6,458 meters or 21,184 feet) dominates the city.

Eastward from La Paz and through the peaks of the Eastern Cordillera, an extremely precipitous road that hugs the walls of sheer valley drops, descends to sub-tropical plains known as the Yungas‚ÄĒan Aymara word which roughly translates as ‚ÄúWarm Lands‚ÄĚ or ‚ÄúWarm Valleys.‚ÄĚ

North and east of the Andes and Yungas is the Oriente (eastern) region which consists of open grasslands, swamps, and tropical forests. It supports the greatest variety of wildlife in the nation, as well as the nation's second largest population center, Santa Cruz, the fastest-growing of Bolivia's regional economies.

The Valles (valleys) form south-central Bolivia. The region consists of gently sloping hills and broad valleys. Open grasslands and many farms cover the land. The Valles produce much of the nation's food and are home to the so-called garden cities of Cochabamba, Sucre, and Tarija which all enjoy a moderate year-round climate.

History

Pre-colonial period

There is evidence of human habitation in the Andean region as far back as 10,000 years ago. Beginning about 100 C.E., a major Indian civilization called the Tiwanaku culture developed at the southern end of Lake Titicaca. The Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) Indians built gigantic monuments and carved statues out of stone. However, their civilization declined rapidly during the thirteenth century, possibly due to an extended drought.

By the late fourteenth century, a warlike tribe called the Aymara controlled much of western Bolivia. The Inca Indians of Peru defeated the Aymara during the fifteenth century and made Bolivia part of their huge empire. They controlled the area until the Spanish conquest in 1538. The Incas generally forced their religion, customs, and language, Quechua, on their defeated rivals. But the Aymara resisted full assimilation, and maintained their separate language and many customs.

Colonial period

During most of the Spanish colonial period, Bolivia was a territory called "Upper Peru" or "Charcas" and was under the authority of the Viceroy of Lima. Local government came from the Audiencia de Charcas located in Chuquisaca (modern Sucre). Bolivian silver mines produced much of the Spanish empire's wealth, and Potosí, site of the famed Cerro Rico ("Rich Hill") was, for many years, the largest city in the Western Hemisphere. A steady stream of enslaved Indians served as the mining labor force. As Spanish royal authority weakened during the Napoleonic wars, sentiment against colonial rule grew.

The Republic (1809)

Bolivia claimed its independence in 1809 as Spain was losing its power in the world. Sixteen years of struggle followed. On August 6, 1825 the republic was established and named for Venezuelan general and leader of South American independence, Simón Bolívar.

In 1829, Andres Santa Cruz, one of Bolivar's generals, became Bolivia's first president. During his administration Bolivia enjoyed the most glorious period of her history with great social and economic advancement.

But Santa Cruz was overthrown in 1839, beginning a period of successive corrupt dictatorships that ruled Bolivia until the late 1800s. Rebellions against them were frequent.

During this period, Bolivia became embroiled in several debilitating regional conflicts, which resulted in the loss of over half of its territory. During the War of the Pacific (1879 ‚Äď 1983), Bolivia lost its seacoast, and the adjoining rich nitrate fields, together with the port of Antofagasta, to Chile.

An increase in the world price of silver brought Bolivia a measure of relative prosperity and political stability in the late 1800s. During the early part of the twentieth century, with the silver mines depleted, the sale of tin became the country's most important source of wealth.

A succession of governments, espousing laissez-faire capitalist policies, was controlled by an economic and social elite that did little to create an economy based on genuine production of goods and services. Rather, they acquired wealth by controlling and selling natural resources. The living conditions of the indigenous people, who constituted most of the population, remained deplorable. Forced to work under primitive conditions in the mines almost like slaves, they were denied access to education, economic opportunity, or political participation.

In 1932, Bolivia and Paraguay fought over ownership of the Gran Chaco, a large lowland plain bordering the two countries thought to be rich in oil. Bolivia was defeated in 1935 and eventually gave up most of the disputed land. Some years later it was found that there were no oil resources in the Chaco.

Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (1951)

The disastrous Chaco War led to growing dissatisfaction with the ruling elite, resulting in the emergence of the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR), a broadly based left-wing party. Denied victory in the 1951 presidential elections, in 1952 the MNR led a successful revolution. Under President Víctor Paz Estenssoro, the MNR introduced universal adult suffrage, carried out a sweeping land reform, promoted rural education, and nationalized the country's largest tin mines.

Victor Paz served as president until 1956. Under Bolivia's constitution, he could not serve more than one term at a time. Another leader of the Revolutionary Movement, Hernan Siles Zuazo, was then elected president. He served until 1960, when Paz was reelected. But a military uprising forced Paz from office in 1964.

In the mid-1960s, Che Guevara, a Cuban communist leader and colleague of Fidel Castro, tried to mount another revolution in Bolivia. But the very Bolivian peasantry, whom he had come to liberate, betrayed him to Bolivian troops, who killed him in 1967.

From Paz’s ouster in 1964 through the 1970s, control of the Bolivian government changed hands repeatedly, mostly after revolts by rival military officers. Alarmed by public disorder, the military, the MNR, and others installed Colonel (later General) Hugo Banzer Suárez as president in 1971. Banzer ruled with MNR support from 1971 to 1978. The economy expanded and grew impressively during most of Banzer's presidency, but human rights violations and eventual fiscal crises undercut his support. He was forced to call new elections in 1978, and Bolivia once again entered a period of political turmoil.

Military governments (1980)

Successive elections in the 1970s led to coups, counter-coups, and caretaker governments. After a military rebellion in 1981 forced out president Luis Garc√≠a Meza, whose government was notorious for human rights abuses, narcotics trafficking, and economic mismanagement, three other military governments in 14 months struggled with Bolivia's growing problems. Unrest forced the military to convoke the congress elected in 1980 and allow it to choose a new chief executive. In October 1982, 22 years after the end of his first term of office (1956 ‚Äď 1960), Hern√°n Siles Zuazo again became president. Severe social tension, exacerbated by economic mismanagement and weak leadership, forced him to call early elections and relinquish power a year before the end of his constitutional term.

Liberalizing the economy

By the end of the twentieth century, inflation had been brought under control, the economy was growing faster than the regional average, and the Bolivian peso, renamed the boliviano, was stabilized. Moreover, the threat of military coups had diminished, and Bolivia's government had gained recognition as one of the more stable political systems in South America.

The government's free market and privatization policies and the relatively robust economic growth of the mid-1990s continued until regional, global, and domestic factors contributed to a decline in economic growth. Job creation remained limited throughout this period and public perception of corruption was high. Both factors contributed to increasing social protests during the second half of Banzer's term.

At the outset of his government, President Banzer launched a policy of using special police units to physically eradicate Bolivia's illegal coca. The policy produced a sudden and dramatic four-year decline in Bolivia's illegal coca crop to the point that Bolivia became a relatively small supplier of coca for cocaine. Those left unemployed by coca eradication streamed into the cities, especially El Alto the slum neighbor of La Paz, exacerbating social tensions and giving rise to a new indigenous political movement.

In 2002, Gonzalo S√°nchez de Lozada again became president, pledging to continue economic reforms and to create jobs. In February 2003, rioting took place in protest against a proposed income tax, which the government then withdrew. In October, S√°nchez resigned after two months of rioting and strikes over a gas-exporting project that protesters believed would benefit foreign companies more than Bolivians. His vice president, Carlos Mesa, best known as a journalist and historian with little experience in government, replaced him.

Mesa subsequently won approval for exporting natural gas in a July 2004 referendum. However, increases in fuel prices, autonomy for the Santa Cruz province, and other issues sparked a series of demonstrations in early 2005 that threatened to plunge Bolivia into chaos. Mesa offered some concessions, but when some of the protests continued he offered to resign (March 2005). Congress rejected his resignation, and Mesa, who remained popular with many Bolivians, attempted to rally his supporters.

Large-scale protests led to Congress approving a confiscatory hydrocarbons law on May 17, 2005. After a brief pause, however, demonstrations resumed, particularly in La Paz and El Alto. President Mesa again offered his resignation June 6, 2005, and Eduardo Rodriguez, the president of the Supreme Court, assumed office in a constitutional transfer of power. Rodriguez announced that he was a transitional president, and called for early elections within six months.

Movement Towards Socialism

On December 18, 2005, Evo Morales, illegal-coca agitator and indigenous leader of the MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) party, was elected to the presidency by 54 percent of the voters, an unprecedented absolute majority in Bolivian elections. Morales pledged to nationalize hydrocarbons and alleviate poverty and discrimination towards indigenous Bolivians. During his campaign, Morales promised to exert more government control over natural gas reserves and to re-examine the current coca eradication programs. Morales was highly critical of the "neo-liberal" economic policies that have been implemented in Bolivia over the past several decades. On January 22, 2006, Morales and his vice president, Alvaro García Linera, were inaugurated into office.

For the first time since the Spanish Conquest in the early 1500s, Bolivia, a nation with a majority indigenous population, has an indigenous leader, and Morales has stated that the 500 years of colonialism are now over, and that the era of autonomy has begun.

Morales is seen as part of a growing trend in Latin America that rejects the free market policies of the 1990s in favor of populist policies aimed at redressing social and economic inequalities. On April 29, 2006, Morales signed a pact with Cuba and Venezuela that rejects a U.S.-backed hemispheric pact, and promises a socialist version of regional commerce and cooperation.

However, this recent turn to ‚Äúsocialism‚ÄĚ has little in common with traditional socialism, which advocated control of the means of production by the masses. Bolivia has suffered negative economic growth as it has fought to divide profits from its natural resources through various political schemes, rather than increase production of goods. Bolivians historically suffer from being unable to keep what they produce, either because they were enslaved or their government overtaxed them. This has undermined the ability to achieve economic independence and resulted in collective psychological defeat.

Amidst allegations that Morales rigged the 2019 Bolivian general election and after widespread protests against his rule, Morales resigned on November 10, 2019, shortly after the military demanded his resignation. He fled to Mexico and was granted asylum there.

Interim government 2019‚Äď2020

Opposition Senator Jeanine √Ā√Īez's declared herself interim president, claiming constitutional succession after the president, vice president and both head of the legislature chambers. She was confirmed as interim president by the constitutional court who declared her succession to be constitutional and automatic.

In April 2020, the interim government took out a loan of more than $327 million from the International Monetary Fund to meet the country's needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. New elections were scheduled for May 2020, but were delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic until October 18, 2020.

Government of Luis Arce: 2020‚Äďpresent

On November 8, 2020, Luis Arce was sworn in as President of Bolivia alongside his Vice President David Choquehuanca. In February 2021, the Arce government returned an amount of around $351 million to the IMF. This comprised a loan of $327 million taken out by the interim government in April 2020 and interest of around $24 million. The government said it returned the loan to protect Bolivia's economic sovereignty and because the conditions attached to the loan were unacceptable.

Economy

Bolivia is rich in natural resources. But its economic development has been limited for several reasons:

- Traditional elites, when they have ruled, have sold natural resources for personal wealth without developing the economy as a whole.

- Revolutionaries, when they have ruled, have tried to "divide the economic pie," but have lacked an understanding of genuine wealth creation, thus, like in other socialist countries there has been economic decline.

- Persisting obstacles for economic competition include an inadequate transportation infrastructure and the nation's landlocked location.

The revolution of 1952 brought agrarian reform based on the break-up of large agricultural estates and the nationalization of mines. These reforms, which increased wages, also resulted in a decrease in agricultural production, and a drastic drop in mineral output. The government, facing demands from powerful leftist labor unions, failed to lay off surplus miners. It also failed to promote greater efficiency in many other sectors of the economy.

Thus, despite the political and social reforms embodied in the revolution, the rate of national economic growth remained extremely low. The economy, largely dependent on the earnings from tin exportation, fluctuated wildly with world tin prices. In the early 1980s, the nation's businesses stagnated as a result of falling tin prices, bad harvests, debt repayments, and inflation that became hyperinflation.

In 1985, the government of President V√≠ctor Paz Estenssoro, which had initiated the reforms of 1952, enacted some of the continent's toughest austerity measures and dropped the inflation rate from 24,000 percent to less than 10 percent. In the 1990s, the economy grew rapidly, and billions of dollars in new investment came into Bolivia after the administration of Gonzalo S√°nchez de Lozada (1993 ‚Äď 1997) privatized nearly the entire state-run economy. However, these market-oriented reforms did not fundamentally change the government's centralized nature, fully open the economy, or create the technical expertise and entrepreneurial spirit important for economic growth. Nearly all parties attempted to gain wealth by gaining control of the natural resources and selling them rather than using them as a national endowment.

Bolivia has the second-largest reserves of natural gas in South America, but the 2004 referendum which partly re-nationalized Bolivia's hydrocarbon industries, created chaos in the industry.

Bolivia's trade with neighboring countries is growing, in part because of several regional preferential trade agreements it has negotiated. Bolivia is a member of the Andean Community and enjoys nominally free trade with other member countries (Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela). Bolivia began to implement an association agreement with Mercosur (Southern Cone Common Market) in March 1997. The agreement provides for the gradual creation of a free trade area covering at least 80 percent of the trade between the parties over a 10-year period, though economic crises in the region have derailed progress at integration. The U.S. Andean Trade Preference and Drug Enforcement Act (ATPDEA) allows numerous Bolivian products to enter the United States free of duty on a unilateral basis, including alpaca and llama products and, subject to a quota, cotton textiles.

The United States remains Bolivia's largest trading partner. Bolivia's major exports to the United States are tin, gold, jewelry, and wood products. Its major imports from the United States are computers, automobiles, wheat, and machinery. A bilateral investment treaty between the United States and Bolivia came into effect in 2001.

Demographics

The vast majority of Bolivians are mestizo (with the indigenous component higher than the European one). The largest of the approximately three dozen indigenous groups are the Quechua-speaking groups, the Aymara, Chiquitano, and Guaraní.

Bolivia is one of the least-developed countries in South America. Almost two-thirds of its people, many of whom are subsistence farmers, live in poverty. Population density ranges from less than one person per square kilometer in the southeastern plains to about 10 per square kilometer in the central highlands.

The great majority of Bolivians are Roman Catholic (the official religion), although Protestant denominations are expanding strongly. Islam is practiced by the descendants of Middle Easterners. There is also a small, yet influential, Jewish community. More than 3 percent of Bolivians practice the Baha'í faith, giving Bolivia one of the largest percentages of Baha'í practitioners in the world. Due to extensive Mormon missionary efforts, there is a substantial Mormon demographic, and there is a temple in Cochabamba. A colony of Mennonites resides near Santa Cruz. Many indigenous communities interweave pre-Columbian and Christian symbols in their worship.

In Bolivia, about half of the people speak Spanish as their first language, although Aymara and Quechua are also common. Approximately 90 percent of children attend primary school but often for a year or less. The literacy rate is low in many rural areas.

The cultural development of present-day Bolivia is divided into three distinct periods: pre-Columbian, colonial, and republican. Important archaeological ruins, gold and silver ornaments, stone monuments, ceramics, and weavings remain from several important pre-Columbian cultures. Major ruins include Tiwanaku, Samaipata, Incallajta, and Iskanwaya. The country abounds in other sites that are difficult to reach and have seen little archaeological exploration.

Culture and the Future of Bolivia

Bolivian culture has many Inca, Aymara, and other indigenous influences in religion, music, and clothing, depending upon the region of the country, isolation of the cultures, and contact with European (Spanish) culture. The best known fiesta is the UNESCO heritage "El carnaval de Oruro." Entertainment includes soccer, which is the national sport and played in many side street corners. Zoos are also a popular attraction.

Since Spanish colonialism, the culture of Bolivia has promoted the myth that economic health is based upon control of natural resources. However, like the Spanish Empire, which became a small economy in Europe when its gold reserves were spent, Bolivia continues its economic woes by depending solely on income from its natural resources rather than industrial production.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ CIA, Bolivia The World Factbook. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Bolivia). International Monetary Fund (10 October 2023).

- ‚ÜĎ GINI index (World Bank estimate) ‚Äď Bolivia The World Bank. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Bolivia Human Development Report. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albiston, Isabel, et al. Lonely Planet Bolivia. Lonely Planet, 2019. ISBN 978-1786574732

- Dangl, Benjamin. The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia. AK Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1849353465

- Jacobs, Daniel. The Rough Guide to Bolivia. Rough Guides, 2018. ISBN 978-0241306291

- Thomson, Sinclair, Rossana Barragán, Xavier Albó, Seemin Qayum, and Mark Goodale (eds.). The Bolivia Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press Books, 2018. ISBN 978-0822371526

External links

All links retrieved March 20, 2024.

- Bolivia CIA, The World Factbook

- BolPress

- Bolivia Lonely Planet

- Bolivia Human Rights Watch

- Bolivia Country Profile BBC

- Bolivia US Department of State

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.