Bonsai

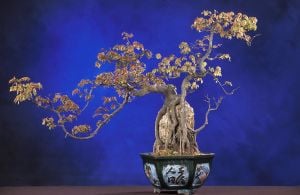

Bonsai (盆栽, literally “tray-planted” or "potted plant") is the art of aesthetic miniaturization of trees by training them and growing them in containers. Bonsai can be developed from seeds or cuttings, from young trees, or from naturally occurring stunted trees transplanted into containers. Most bonsai range in height from 5 centimeters (2 inches) to 1 meter (3.33 feet). Bonsai cultivation includes techniques for pruning roots and branches, wiring and shaping, watering, and repotting in various styles of containers. Bonsai may live for a century or more, if cared for properly, and prized specimens are handed down as family heirlooms.

Penzai (盆栽; pun-sai), the practice of cultivating single specimen trees in wooden trays or earthenware pots, originated in China during the Han dynasty and was introduced to Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), along with Zen Buddhism. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the Japanese arts reached their peak, the art of bonsai became highly evolved. In the late nineteenth century, after Japan opened its doors to the world, increasing demand resulted in a commercial bonsai industry and the use of innovative techniques and plant species other than the traditional pines, azaleas, and maples.

History

Bonsai is believed to have originated in China nearly 2,000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty. "Bonsai" is a Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese penzai (盆栽; pun-sai), the practice of cultivating single specimen trees in wooden trays or earthenware pots. The trees were trained in naturalistic shapes, and the gnarled trunks of early specimens often looked like animals, dragons, and birds. Grotesque, animal-like trunk and root formations are still highly prized by the Chinese.[2] The practice eventually developed into new forms in parts of China, Korea, and Vietnam, but it reached its greatest level of sophistication in Japan.

Bonsai was introduced to Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) along with Zen Buddhism. A possible reference to it in a Japanese scroll, dating to 1195, suggests that bonsai may have already arrived in Japan before the thirteenth century.[3] The Kasuga-gongen-genki, a picture scroll by Takashina Takakane (1309), contains the earliest confirmed Japanese record of dwarfed potted trees. A rhymed prose essay from the same period, Rhymeprose on a Miniature Landscape Garden, by the Japanese Zen monk Kokan Shiren, outlines the aesthetic principles for bonsai, bonseki, and garden architecture itself. Yoshida Kenko (1283–1351), a Japanese satirist, wrote a well-known quote, "To appreciate and find pleasure in curiously curved potted trees is to love deformity.”[4]

The Japanese used miniaturized trees grown in containers to decorate their homes and gardens.[5] By the fourteenth century, bonsai was viewed as a highly-refined art form. During the Tokugawa period (1603–1868), landscape gardening attained new importance when cultivation of plants such as azalea and maples became a pastime of the wealthy. Dwarf potted trees (鉢の木, hachi-no-ki, "a tree in a pot") were symbols of prestige among the aristocracy. At this time, naturally-dwarfed trees were transplanted from the wild; the practices of pruning and training did not develop until later.[6]

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the Japanese arts reached their peak, the art of bonsai became highly evolved. The containers used at that time seem to be slightly deeper than those used today. The main principle was now the removal of all but the most important parts of the plant, and its reduction to the most essential elements. Bonsai became popular among the general populace, increasing the demand for naturally-dwarfed wild trees and stimulating the development of artificial cultivation.

Different styles of bonsai began to emerge, as artists introduced other elements of cultural importance in their bonsai plantings, such as rocks, supplementary and accent plants, and even small buildings and people (the art of bon-kei). They also began to reproduce entire miniature natural landscapes (sai-kei).

After the Meiji Restoration (1868), when Japan opened itself to the world after 230 years of isolation, travelers to Japan began to spread the word of the miniature trees in ceramic containers which mimicked aged, mature wild trees in nature. In the latter part of the century, bonsai were displayed at exhibitions in London, Vienna, and at the Paris World Exhibition in 1900. The upsurge in demand led to commercial production by artists who used wire, bamboo skewers, and special growing techniques to train young trees to look like bonsai. Nurseries were dedicated solely to the growth and training of bonsai trees for export; and different plants, which were appropriate for other climates, which produced neater foliage and had suitable growth characteristics, came into use. Techniques such as raising trees from seed or cuttings, and the styling and grafting of unusual or tender material onto hardy root stock, were further developed.

Modern bonsai reflects changing tastes and the great variety of countries, cultures, and conditions in which it is now practiced. While Japanese bonsai artists still prefer to use traditional native species such pines, azaleas, and maples, bonsai growers in other countries are more open to innovation and novelty.[7]

The oldest known living bonsai trees are in the collection at Happo-en (a private garden and restaurant) in Tokyo, Japan, where there are bonsais between 400 and 800 years old.

Aesthetics

The cultivation of bonsai, like other Japanese arts such as tea ceremony and flower arranging, is considered a form of Zen practice. The combination of natural elements with the controlling hand of humans evokes meditation on life and the mutability of all things. A bonsai artist seeks to create a triangular pattern which gives visual balance and expresses the relationship shared by a universal principle (life-giving energy, or deity), the artist, and the tree itself. According to tradition, three basic virtues, shin-zen-bi (standing for truth, goodness and beauty) are necessary to create a bonsai.[8] The expression "heaven and earth in one container" refers to the fact that the bonsai, with its container and soil, is a separate entity, complete in itself, since its roots are not planted in the earth, yet part of nature. A bonsai is positioned off-center in its container because the center symbolizes the point at which heaven and earth meet, and should therefore be left unoccupied. The direct inspiration for bonsai are the gnarled, naturally-dwarfed trees that grow in rocky crevices and overhanging cliffs. The Japanese prize an aged appearance of the trunk and branches, and weathered-looking exposed upper roots, expressing the aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi, “nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.”

The bonsai artist does not duplicate nature, but rather expresses a personal aesthetic philosophy by manipulating it. Japanese bonsai are meant to evoke the essential spirit of the plant being used: In all cases, they must look natural and never show the intervention of human hands. There are several aesthetic principles which are for the most part unbroken, such as the rule that tree branches must never cross and trees should bow slightly forward, never lean back.[9]

The following characteristics are desirable in Japanese bonsai and other styles of container-grown trees:

- Miniaturization. By definition, a bonsai is a tree which is kept small enough to be container-grown while otherwise fostered to have a mature appearance. One way in which bonsai are classified is according to size.

- Gravitas. A sense of physical weight, the illusion of mass, the appearance of maturity or advanced age, and the elusive quality of dignity.

- Leaf Reduction. Leaf reduction varies over the life cycle of a particular bonsai. A bonsai’s leaves might be allowed to attain full size for many years in order to encourage vigor and growth of some other aspect of the bonsai. Prior to exhibiting a bonsai, it is usually desirable to attain a degree of leaf reduction. Leaf reduction may be encouraged by pruning, and is sometimes achieved by the total exfoliation of a bonsai during one part of its growing season. Conifer needles are more difficult to reduce than other sorts of foliage.

- Lignification. This refers to the “woody-ness” of a bonsai’s trunk and branches so that they have a mature appearance. Typically the surface is encouraged to become rough and brown, but in some cases this aesthete will vary, such as in a birch tree bonsai attaining the white color and exfoliating bark of a mature specimen.

- Nebari. Also known as "buttressing," nebari is the visible spread of roots above the growing medium at the base of a bonsai. Nebari helps a bonsai seem grounded and well-anchored and helps a tree look old, mature, and more akin to a full-sized tree.

- Ramification. Ramification is the splitting of branches and twigs into smaller ones. It is encouraged by pruning and may be integrated with practices that promote leaf reduction.

- Deadwood. Bonsai artists sometimes foster certain types of deadwood to be produced by and remain on a bonsai tree, just as scars or bare, dead branches may occur on full-sized trees. Cultivators use deadwood features called jin and shari to simulate age and maturity in a bonsai. Jin is the term used when the bark from an entire branch is removed to create the impression of a snag of deadwood. Shari denotes stripping bark from areas of the trunk to simulate natural scarring from a broken limb or lightning strike.

- Curvature. Bonsai that achieve a sense of age while remaining straight and upright can be especially impressive, but many bonsai rely upon curvature of the trunk to give the illusion of weight and age. Curvature of the trunk that occurs between the roots and the lowest branch is known as tachiagari.

Cultivation

Bonsai are not genetically dwarfed plants. They can be created from nearly any tree or shrub species, and remain small through pot confinement and crown or root pruning. Some specific species are more sought after for use as bonsai material because they have characteristics that make them appropriate for the smaller design arrangements of bonsai. In Japan, varieties of pine, azalea, camellia, bamboo and plum are most often used.

There are several sizes of bonsai. Miniature bonsai can be up to two inches (5 centimeters) high, and take three to five years to mature if started from seeds or cuttings. They may live for several decades. Small bonsai, two to six inches tall, must be trained for five to ten years. Medium bonsai (six to twelve inches in height) and average bonsai (up to two feet high) can be produced in as little as three years. Properly cared for, bonsai can live for hundreds of years, with prized specimens being passed from generation to generation as family heirlooms.

Naturally dwarfed trees collected in the wild often do not adapt to cultivation as bonsai because of the shock resulting from the abrupt change of environment.

Techniques

The small size of the tree and the dwarfing of foliage result from pruning of both the leaves and the roots. Most trees require an annual dormancy period and do not grow roots or leaves at that time. Improper pruning can weaken or kill trees.[10]

Copper or copper-colored aluminium wire wrapped around developing branches and trunks holds the branches in place until they lignify (convert into wood), usually 6-9 months, or one growing season. Some species do not lignify strongly, or are already too stiff or brittle to be shaped and are not conducive to wiring, in which case shaping is accomplished primarily through pruning.[11]

Watering

The limited space in a bonsai pot means that regular attention is needed to ensure the tree is correctly watered. Sun, heat, and wind exposure can dry bonsai trees to the point of drought in a short period of time. While some species can handle periods of relative dryness, others require near-constant moisture. Watering too frequently, or allowing the soil to remain soggy, promotes fungal infections and root rot. Free draining soil is used to prevent waterlogging. Deciduous trees are more at risk of dehydration and will wilt as the soil dries out. Evergreen trees, which tend to cope with dry conditions better, do not display signs of the problem until after damage has occurred.

Repotting

Bonsai are repotted and root-pruned at intervals dictated by the vigor and age of each tree. In the case of deciduous trees, this is done as the tree is leaving its dormant period, generally around springtime. Bonsai are often repotted while in development, and less often as they become more mature. This prevents them from becoming pot-bound and encourages the growth of new feeder roots, allowing the tree to absorb moisture more efficiently.

Young pre-bonsai shoots are often placed in "growing boxes" made from scraps of fenceboard or wood slats. These large boxes allow the roots to grow more freely and increase the vigor of the tree. The tree is then replanted in a smaller "training box," to create a smaller, denser root mass which can be more easily moved into a final presentation pot.

Tools

Special tools are available for the maintenance of bonsai. The most common tool is the concave cutter, a tool designed to prune flush, without leaving a stub. Other tools include branch bending jacks, wire pliers. and shears of different proportions for performing detail and rough shaping.

Soil and fertilization

Opinions about soil mixes and fertilization vary widely among practitioners. Some promote the use of organic fertilizers to augment an essentially inorganic soil mix, while others will use chemical fertilizers freely. Bonsai soil is primarily a loose, fast-draining mix of components,[12] often a base mixture of coarse sand or gravel, fired clay pellets or expanded shale combined with an organic component such as peat, bark or moss. In Japan, volcanic soils based on clay are preferred, such as akadama, or "red ball" soil, and kanuma, a type of yellow pumice used for azaleas and other calcifuges.

Location and overwintering

Most traditional bonsai are temperate climate trees and are kept outside all year. They require full sun in summer and usually a near-freezing dormancy period in winter. Depending on how hardy the tree species is, protection from very low temperatures may be required. Certain tropical species can survive winter without a dormancy period, and can therefore be kept indoors all year. Indoor bonsai are sometimes artificially exposed to cold by using a refrigerator to simulate winter temperatures.

Outdoor bonsai can be brought into the house occasionally for appreciation and enjoyment. In Japan, they are traditionally displayed in a special alcove (tokonoma) or on small tables in a living room, and later returned to their outdoor bonsai stands. A blossoming apricot or plum tree is sometimes displayed during the New Year.

Containers

Bonsai pots have drainage holes typically covered with a plastic screen or mesh to prevent soil from escaping.

Containers come in a variety of shapes and colors and can be glazed or unglazed. They may be round, oval, square, rectangular, octagonal, or lobed. Containers with straight sides and sharp corners are generally better suited to formally presented plants, while oval or round containers might be used for plants with informal shapes. Most evergreen bonsai are placed in unglazed pots, while deciduous trees are planted in glazed pots. It is aesthetically important that the color and proportion of the pot harmonize with the tree. Some pots are highly collectible, such as ancient Chinese or Japanese pots made in regions with experienced pot makers, such as Tokoname, Japan.

In a rectangular or oval container, the tree is placed not quite halfway between the midpoint and one side, depending on the shape of the branches. In a round or square container, the tree is placed slightly off-center. Bonsai are usually trained to have a particular side, which is turned to the front when on display.

Common styles

In English, the most common styles include: Formal upright, slant, informal upright, cascade, semi-cascade, raft, literati, and group/forest.

- The formal upright style, or Chokkan, is characterized by a straight, upright, tapering trunk. The trunk and branches of the informal upright style, or Moyogi, may incorporate pronounced bends and curves, but the apex of the informal upright is always located directly over where the trunk begins at the soil line.

- Slant-style, or Shakan, bonsai possess straight trunks like those of bonsai grown in the formal upright style. However, the slant style trunk emerges from the soil at an angle, and the apex of the bonsai will be located to the left or right of the root base.

- Cascade-style, or Kengai, bonsai are modeled after trees which grow over water or on the sides of mountains. The apex, or tip of the tree in the Semi-cascade-style, or Han Kengai, bonsai extend just at or beneath the lip of the bonsai pot; the apex of a (full) cascade style falls below the base of the pot.

- Raft-style, or Netsuranari, bonsai mimic a natural phenomenon that occurs when a tree topples onto its side (typically due to erosion or another natural force) and branches along the exposed side of the trunk, grow as if they are a group of new trunks. Sometimes, roots will develop from buried portions of the trunk. Raft-style bonsai can have sinuous, straight-line, or slanting trunks, all giving the illusion that they are a group of separate trees.

- The literati style is characterized by a generally bare trunk line, with branches reduced to a minimum, and typically placed higher up on a long, often contorted trunk. This style derives its name from the Chinese literati, who were often artists, and some of whom painted Chinese brush paintings, like those found in the ancient text, The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, depicting pine trees that grew in harsh climates, struggling to reach sunlight. In Japan, the literati style is known as bunjin-gi (文人木). (Bunjin is a translation of the Chinese phrase wenren meaning "scholars practiced in the arts," and gi is a derivative of the Japanese word, ki, for "tree").

- The group or forest style, or Yose Ue, comprises a planting of more than one tree (typically an odd number if there are more than three trees, and never four because that is an unlucky number in Japan) in a bonsai pot. The trees are usually the same species, with a variety of heights employed to add visual interest and to reflect the age differences encountered in mature forests.

- The root-over-rock style, or Sekijoju, is a style in which the roots of a tree (typically a fig tree) are wrapped around a rock. The rock is at the base of the trunk, with the roots exposed to varying degrees.

- The broom style, or Hokidachi, is employed for trees with extensive, fine branching, often with species like elms. The trunk is straight and upright. It branches out in all directions about 1/3 of the way up the entire height of the tree. The branches and leaves form a ball-shaped crown which can also be very beautiful during the winter months.

- The multi-trunk style, or Ikadabuki, has all the trunks growing out of one root system, and it actually is one single tree. All the trunks form one crown of leaves, in which the thickest and most developed trunk forms the top.

- The growing-in-a-rock, or Ishizuke, style means the roots of the tree are growing in the cracks and holes of the rock. There is not much room for the roots to develop and take up nutrients. These trees are designed to visually represent that the tree has to struggle to survive.

Terminology

- Penjing—Chinese precursor to bonsai

- Saikei—gardens using bonsai

- Niwaki—Japanese art of tree pruning

- Topiary—western art of tree pruning

Size classifications

| Class | Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm | in | |||

| tiny | Mame | Keshi-tsubu | up to 2.5 | up to 1 |

| Shito | 2.5 – 7.5 | 1–3 | ||

| small | Shohin | Gafu | 13 – 20 | 5–8 |

| Komono | up to 18 | up to 7.2 | ||

| Myabi | 15–25 | 6–10 | ||

| medium | Kifu | Katade-mochi | up to 40 | 16 |

| medium to large | Chu/Chuhin | 40–60 | 16–24 | |

| large | Dai/Daiza | Omono | up to 120 | up to 48 |

| Bonju | over 100 | over 40 | ||

Not all sources agree on the exact range of sizes. There are a number of specific techniques and styles associated with mame and shito sizes, the smallest bonsai.

See also

Notes

- ↑ William N. Valavanis, "The History of Goshin (Protector of the spirit)," North American Bonsai Federation Newsletter #1, Feature #5 (December 2002). Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ↑ The Bonsai Site, A Detailed History of Bonsai. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Thomas Pakenham, Remarkable Trees of the World (New York: Norton, ISBN 9780393049114).

- ↑ Peter Del Tredici, Early American Bonsai: The Larz Anderson Collection of the Arnold Arboretum, Arnoldia. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ↑ The Bonsai Site, A Detailed History of Bonsai. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The Bonsai Site, An Introduction to Bonsai. Retrieved June 13, 2008

- ↑ Penjing, Chinese Potted Landscapes. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ↑ Colin Lewis, The Bonsai Handbook (Advanced Marketing Ltd. 2003, ISBN 1-903938-30-9).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Mike Smith, It's All In The Soil, Norfolk Bonsai (Spring 2007). Retrieved June 13, 2008

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chan, Peter. Bonsai Secrets: Designing, Growing, and Caring for your Miniature Masterpieces. Pleasantville, NY: Reader's Digest, 2006. ISBN 978-0762106240

- Coussins, Craig. Bonsai Master Class. New York: Sterling, 2006. ISBN 978-1402735479

- Lang, Susan. Bonsai. Menlo Park, Calif: Sunset Pub., 2003. ISBN 978-0376030467

- Lesniewicz, Paul. Bonsai: The Complete Guide to Art and Technique. Poole, Dorset: Blandford Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0713713626

- Perl, Philip. Miniatures and Bonsai. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1979. ISBN 978-0809426430

- Samson, Isabelle, and Rémy Samson. The Creative Art of Bonsai. London: Hamlyn, 2000. ISBN 978-0600601807

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.