| Brachiopods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Living brachiopods. | ||||

| Scientific classification | ||||

| ||||

| Subphyla and classes | ||||

|

See Classification |

Brachiopoda (from Latin bracchium, arm + New Latin -poda, foot) is a major invertebrate phylum, whose members, the brachiopods or lamp shells, are sessile, two-shelled, marine animals with an external morphology resembling bivalves (that is, "clams") of phylum Mollusca to which they are not closely related. Brachiopods are found either attached to substrates by a structure called a pedicle or unattached and resting on muddy bottoms. Brachiopods are suspension feeders with a distinctive feeding organ called a lophophore found only in two other suspension-feeding animal phyla, the Phoronida (phoronid worms) and the usually colonial Ectoprocta or Bryozoa. Characterized by some as a "crown" of ciliated tentacles, the lophophore is essentially a tentacle-bearing ribbon or string that is an extension (either horseshoe-shaped or circular) surrounding the mouth.

The brachiopods were a dominant group during the Paleozoic era (542-251 mya), but are less common today. Modern brachiopods range in shell size from less than five mm (1/4 of an inch) to just over eight cm (three inches). Fossil brachiopods generally fall within this size range, but some adult species have a shell of less than one millimeter across, and a few gigantic forms measuring up to 38.5 cm (15 inches) in width have been found. Some fossil forms exhibit elaborate flanges and spines. The brachiopod genus Lingula has the distinction of being the oldest, relatively unchanged animal known.

Modern brachiopods generally live in areas of cold water, either near the poles or in deep parts of the ocean.

Types of brachiopods

Brachiopods come in two easily distinguished varieties. Articulate brachiopods have a hinge-like connection or articulation between the shells, whereas inarticulate brachiopods are not hinged and are held together entirely by musculature.

Brachiopods‚ÄĒboth articulate and inarticulate‚ÄĒare still present in modern oceans. The most abundant are the terebratulides (class Terebratulida). The perceived resemblance of terebratulide shells to ancient oil lamps gave the brachiopods their common name "lamp shell."

The phylum most closely related to Brachiopoda is probably the small phylum Phoronida (known as "horseshoe worms"). Along with the Bryozoa/Ectoprocta and possibly the Entoprocta/Kamptozoa, these phyla constitute the informal superphylum Lophophorata. They are all characterized by their distinctive lophophore, a "crown" of ciliated tentacles used for filter feeding. This tentacle "crown" is essentially a tentacle-bearing ribbon or string that is an extension (either horseshoe-shaped or circular) surrounding the mouth (Smithsonian 2007; Luria et al. 1981).

Brachiopods and bivalves

Despite cursory resemblance, bivalves and brachiopods differ markedly in many ways.

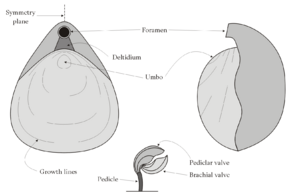

Bivalves usually have a plane of symmetry parallel to the hinge and lying between the shells, whereas most brachiopods have a plane of bilateral symmetry perpendicular to the hinge and bisecting both of the shells. Each brachiopod shell is symmetrical as an individual shell, but the two of them differ in shape from each other.

Bivalves use adductor muscles to hold the two shells closed and rely on ligaments associated with the hinge to open them once the adductor muscles are relaxed; in contrast, brachiopods use muscle power for both opening (internal diductor and adjustor muscles) and closing (adductor muscles) the two shells, whether they are of the hinged (articulate) or not hinged (inarticulate) type.

Most brachiopods are attached to the substrate by means of a fleshy "stalk" or pedicle. In contrast, although some bivalves (such as oysters, mussels, and the extinct rudists) are fixed to the substrate, most are free-moving, usually by means of a muscular "foot."

Brachiopod shells may be either phosphatic or (in most groups) calcitic. Rarely, brachiopods may produce aragonitic shells.

Evolutionary history

| Paleozoic era (542 - 251 mya) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambrian | Ordovician | Silurian | Devonian | Carboniferous | Permian |

The earliest unequivocal brachiopods in the fossil record occur in the early Cambrian period (542-488 mya), with the hingeless, inarticulate forms appearing first, followed soon thereafter by the hinged, articulate forms. Putative brachiopods are also known from much older upper Neoproterozoic era (1,000-542 mya) strata, although the assignment remains uncertain.

Brachiopods are extremely common fossils throughout the Paleozoic era (542-251 mya). During the Ordovician (488-444 mya) and Silurian (444-416 mya) periods, brachiopods adapted to life in most marine environments and became particularly numerous in shallow water habitats, in some cases forming whole banks in much the same way as bivalves (such as mussels) do today. In some places, large sections of limestone strata and reef deposits are composed largely of their shells.

Throughout their long history the brachiopods have gone through several major proliferations and diversifications, and have also suffered from major extinctions as well.

The major shift came with the Permian extinction about 251 mya. Before this extinction event, brachiopods were more numerous and diverse than bivalve mollusks. Afterwards, in the Mesozoic era (251-65 mya), their diversity and numbers were drastically reduced, and they were largely replaced by bivalve mollusks. Mollusks continue to dominate today and the remaining orders of brachiopods survive largely in fringe environments of more extreme cold and depth.

The inarticulate brachiopod genus Lingula has the distinction of being the oldest, relatively unchanged animal known. The oldest Lingula fossils are found in Lower Cambrian rocks dating to roughly 550 million years ago.

The origin of brachiopods is unknown. A possible ancestor is a sort of ancient "armored slug" known as Halkieria that was recently been found to have had small brachiopod-like shields on its head and tail.

It has been suggested that the slow decline of the brachiopods over the last 100 million years or so is a direct result of (1) the rise in diversity of filter feeding bivalves, which have ousted the brachiopods from their former habitats; (2) the increasing disturbance of sediments by roving deposit feeders (including many burrowing bivalves); and/or (3) the increased intensity and variety of shell-crushing predation. However, it should be noted that the greatest successes for the burrowing bivalves have been in habitats, such as the depths of sediments below the surface of the sea floor, that have never been adopted by the brachiopods.

The abundance, diversity, and rapid development of brachiopods during the Paleozoic era make them useful as index fossils when correlating strata across large areas.

Classification

| Brachiopod Taxonomy Extant taxa in green, extinct taxa in grey | |||

| Subphyla | Classes | Orders | Extinct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linguliformea | Lingulata | Linguilida | no |

| Siphonotretida | Ordovician | ||

| Acrotretida | Devonian | ||

| Paterinata | Paterinida | Ordovician | |

| Craniiformea | Craniforma | Craniida | no |

| Craniopsida | Carboniferous | ||

| Trimerellida | Silurian | ||

| Rhychonelliformea | Chileata | Chileida | Cambrian |

| Dictyonellidina | Permian | ||

| Obolellata | Obolellida | Cambrian | |

| Kutorginata | Kutorginida | Cambrian | |

| Strophomenata | Orthotetidina | Permian | |

| Triplesiidina | Silurian | ||

| Billingselloidea | Ordovician | ||

| Clitambonitidina | Ordovician | ||

| Strophomenida | Carboniferous | ||

| Productida | Permian | ||

| Rhynchonellata | Protorthida | Cambrian | |

| Orthida | Carboniferous | ||

| Pentamerida | Devonian | ||

| Rhynchonellida | no | ||

| Atrypida | Devonian | ||

| Spiriferida | Jurassic | ||

| Thecideida | no | ||

| Athyridida | Cretaceous | ||

| Terebratulida | no | ||

In older classification schemes, phylum Brachiopoda was divided into two classes: Articulata and Inarticulata. Since most orders of brachiopods have been extinct since the end of the Paleozoic era 251 million years ago, classifications have always relied extensively on the morphology (that is, the shape) of fossils. In the last 40 years further analysis of the fossil record and of living brachiopods, including genetic study, has led to changes in taxonomy.

The taxonomy is still unstable, however, so different authors have made different groupings. In their 2000 article as part of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Williams, Carlson, and Brunton present current ideas on brachiopod classification; their grouping is followed here. They subdivide Brachiopoda into three subphyla, eight classes, and 26 orders. These categories are believed to be approximately phylogenetic. Brachiopod diversity declined significantly at the end of the Paleozoic era. Only five orders in three classes include forms which survive today, a total of between 300 and 500 extant species. Compare this to the mid-Silurian period, when 16 orders of brachiopods coexisted.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Buckman, S. S. 1910. ‚ÄúCertain Jurassic (Inferior Oolite) species of ammonites and brachiopoda.‚ÄĚ Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 66: 90-110.

- Harper, E. M. 2005. ‚ÄúEvidence of predation damage in Pliocene Apletosia maxima (Brachiopoda).‚ÄĚ Palaeontology 48: 197-208.

- Luria, S. E., S. J. Gould, and S. Singer. 1981. A View of Life. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8053-6648-2.

- Williams, A., S. J. Carlson, and C. H. C. Brunton. 2000. ‚ÄúBrachiopod classification.‚ÄĚ Part H. in A. Williams et al. (coordinating author), R. L. Kaesler (editor). Volume 2, Brachiopoda (revised). as part of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas. ISBN 0-8137-3108-9.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.