Carol I of Romania

Carol I of Romania, original name Prince Karl Eitel Friedrich Zephyrinus Ludwig of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, later simply of Hohenzollern (April 20, 1839 - October 10, 1914) German prince, was elected Domnitor (Prince) of Romania on April 20, 1866, following the overthrow of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, and proclaimed king on March 26, 1881, with the acquiescence of the Turkish Sultan whose armies were defeated in Romania's 1877 Independence War by the Romanian-Russian army under the command of Prince Charles I. He was, then, the first ruler of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen dynasty which would rule the country until the imposition of a Stalin-directed republic, dictated at gun point in a coup d'etat devised by Dr. Petru Groza, whose government was backed up by the Soviet armies of occupation in 1947; this forced abdication (and later exile) of King Michael I of Romania by his former Soviet allies occurred shortly after the soviet dictator Joseph (Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili) Stalin bestowed the Soviet Order of Victory upon King Michael I for his central role in the overturn of the Germans in Roumania in late August 1944.

During the Independence War of 1877-1878, Prince Charles personally led Romanian troops, and also assumed command of the Russo-Romanian army during the siege of Pleven, (in Romanian, Plevna) with the acquiescence of Russia's Czar Alexander II. The country achieved full independence from the Ottoman Empire (Treaty of Berlin, 1878), acquired access to the Black Sea, and later also acquired the Southern part of the Dobruja from Bulgaria in 1913, but lost Bessarabia in 1878 to its Russian "allies." Domestic political life, still dominated by the country's wealthy landowning families organized around the rival Liberal and Conservative]] parties, was punctuated by two widespread peasant uprisings, in Walachia (the southern half of the country) in April 1888 and in Moldavia (the Northern half) in March 1907.

Unlike Otto of Greece who, also a foreigner, had been installed as the king of Greece after independence from Ottoman rule, Carol I fully embraced his new country and tried to emulate the developing constitutional monarchies of Western Europe. Under Carol, democracy was nurtured, the economy thrived and stability was achieved. From 1947 until 1989, the Communists suppressed his memory but now that Romania is once more free and democratic, this can be celebrated again.

Early life

Carol was born in Sigmaringen as Prince Karl von Hohenzollern Sigmaringen. He was the second son of Karl Anton, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and his wife, Princess Josephine of Baden. After finishing his elementary studies, Karl entered the Cadet School in Münster. In 1857, he was attending the courses of the Artillery School in Berlin. Up to 1866 (when he accepted the crown of Romania), he was a German officer. He took part in the Second War of Schleswig, particularly at the assault of the Fredericia citadel and Dybbøl, experience which would be very useful to him later on in the Russian-Turkish war.

Although he was quite frail and not very tall, prince Karl was reported to be the perfect soldier, healthy, disciplined, and also a very good politician with liberal ideas. He was familiar with several European languages. His family being closely related to the Bonaparte family (one of his grandmothers was a Beauharnais and the other a Murat), they enjoyed very good relations with Napoleon III.

Romania: The search for a ruler

Romania, throwing off Ottoman rule, had chosen Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince (Domnitor) in 1859. Now, they wanted to replace him with a new ruler. Cuza had proven both too authoritarian, as well as having alienated the elite through proposed land-reforms. Romanians thought that a foreign prince, who was already a member of a ruling house, would both "enhance the country's prestige" and "put an end to internal rivalry for the throne."[1] They "began searching Europe for a suitable prince."[2]

Romania was, at the time, under the influence of French culture, so when Napoleon decided to recommend of Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, this weighed heavily in the eyes of Romania's politicians, as did his blood relation to the ruling Prussian family. Ion Brătianu was the leading Romanian statesman who was sent to negotiate with Karl and his family about the possibility of installing Karl on the Romanian throne. Ion Brătianu met privately with Prince Karl at Dusseldorf, where he arrived on Good Friday 1866. The next day he submitted the proposition that Karl become the official ruler ("Domnitorul Romaniei") and Prince of Romania, that is, of both Vallachia and Moldavia (but not Transylvania, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time). Although Prince Karl may have been favorably inclined, he needed the approval or nodding consent of Otto von Bismark, Napoleon III, and Wilhelm II before providing a definitive and positive answer. He replied that while he had enough courage to accept the offer, he had to decline until he had permission to accept from the Kaiser as head of the family. When a letter from the King arrived on April 16, it was not encouraging. In addition to asking whether such a position was sufficiently dignified for a member of the House of Hohenzollern, two issues remained undecided:

(a) Is there to be a union or not? (b) Is there to be a foreign Prince or not? Russia and the Porte are against the union, but it appears that England will join the majority, and if she decides for the union the Porte will be obliged to submit. In the same way both the former States are opposed to the election of a foreign Prince as the ruler of the Danubian Principalities. I have mentioned this attitude to the Porte, and yesterday we received a message from Russia to say that it was not disposed to agree to the project of your son's election, and that it will demand a resumption of the Conference… All these events prevent the hope of a simple solution. I must therefore urge you to consider these matters again… and we must see whether the Paris Conference will reassemble again. Your faithful Cousin and Friend, WILLIAM. P.S.—A note received today from the French Ambassador proves that the Emperor

Napoleon (III) is favorably inclined to the plan. This is very important.[3]

"The position will only be tenable if Russia agrees…on account of her professing the same religion and owing to her geographical proximity and old associations… If you are desirous of prosecuting this affair your son must, above all things, gain the consent of Russia. It is true that up to now the prospect of success is remote…." A "most important interview then took place between Count Bismark and Prince Charles (Karl) at the Berlin residence of the former, who was at the time confined to his house by illness. Bismark opened the conversation with the words:

I have requested your Serene Highness to visit me, not in order to converse with you as a statesman, but quite openly and freely as a friend and an adviser, if I may use the expression. You have been unanimously elected by a nation to rule over them. Proceed at once to the country, to the government of which you have been called! …Ask the King for leave—leave to travel abroad. The King (I know him well) will not be slow to understand, and to see through your intention. You will, moreover, remove the decision out of his hands, a most welcome relief to him, as he is politically tied down. Once abroad, you resign your commission (in the Prussian army of the King), and proceed to Paris, where you will ask the Emperor (Napoleon III) for a private interview.[4]

Ironically, the branch of the Hohenzollern that Carol established in Romania outlasted the German dynasty, which ended in 1918, with Wilhelm's abdication.

On the way to Romania

The former Romanian ruler, Alexander Joan Cuza, had been banished from the country and Romania was in chaos. Since his double election had been the only reason the two Romanian countries (Wallachia and the Principality of Moldavia) were allowed to unite by the European powers of the time, the country was in danger of dissolving. These two states had not been united since the time of Michael the Brave, who very briefly had united all three of the Romanian principalities. The third, Transylvania, did not join until after World War I.

Young Karl had to travel incognito on the railroad Düsseldorf-Bonn-Freiburg-Zürich-Vienna-Budapest, due to the conflict between his country and the Austrian Empire. He traveled under the name of Karl Hettingen. As he stepped on Romanian soil, Brătianu bowed before him and asked him to join him in the carriage (at that time, Romania did not have a railroad system).

On May 10, 1866, Karl entered Bucharest. The news of his arrival had been transmitted through telegraph and he was welcomed by a huge crowd eager to see its new ruler. In Băneasa he was handed the key to the city. As a proverbial sign, on the same day it had rained for the first time in a long period of time. He pledged his oath in French: "I swear to guard the laws of Romania, to maintain its rights and the integrity of its territory."[5]

The constitution

Immediately after arriving in the country, the Romanian parliament adopted, on June 29, 1866, the first Constitution of Romania, one of the most advanced constitutions of its time. This constitution allowed the development and modernization of the Romanian state. In a daring move, the Constitution chose to ignore the country's current dependence on the Ottoman Empire, which paved the way for Independence.

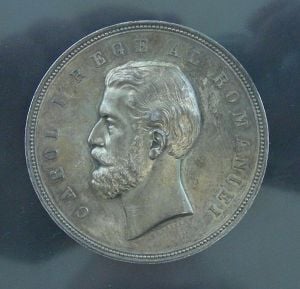

| Silver coin of Carol I, struck 1880 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: (Romanian) CAROL I DOMNUL ROMANIEI or in English, "Carol I, Prince of Romania" | Reverse: (Romanian) ROMANIA 5 L 1880, or in English, "Romania, 5 Leu, 1880" |

Article 82 said, "The ruler's powers are hereditary, starting directly from His Majesty, prince Carol I of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, on male line through the right of first-born, with the exclusion of women and their issue. His Majesty's descendants will be raised in the Eastern Orthodox Religion."

After the proclamation of the Independence (1877), Romania was effectively a kingdom. From 1878, Carol held the title of Royal Highness (Alteţă Regală). On March 15, 1881, the Constitution was modified to state, among other things, that from then on the head of state would be called king, while the heir would be called royal prince. The same year he was crowned King.

The basic idea of all the royalist constitutions in Romania was that the King rules without governing.

Romanian War of Independence with the Ottoman Empire (1877-1878)

On the 31st, a report was received

that the Russians had suffered a severe defeat at Plevna, and were retiring panic-stricken on Sistow; this was confirmed at 9 P.M. by the following dispatch… (i.e., to Prince Carol) in cipher:

'WEDNESDAY, July 19-31, 1877, 3.35 P.M. 'PRINCE CHARLES OF ROUMANIA. 'Headquarters of the Roumanian Army.:

'The Turks having assembled in great force at Plevna are crushing us. Beg you to join, make a demonstration, and, if possible, cross the Danube, as you wish. This demonstration between Jiul and Corabia is indispensible to facilitate my movements.

NICHOLAS" (the Russian Commander, General Nicholas, appointed by Czar Alexander II).[6]

"Prince Charles replied that the Fourth... (i.e., Roumanian) Division would hold Nikopoli, and that the Third occupy the position quitted by the Fourth";... "Prince Charles refused to allow the Third Division to cross, as he had no intention of allowing his army to be incorporated with the Russian."[6]

As king

King Carol was mistakenly reported to be a "cold" person. He was, however, permanently concerned with the prestige of the country and of the dynasty that he had founded. Although he was entirely devoted to his position as a Romanian Prince, and later King, he never forgot his German roots. Very meticulous, he tried to impose his style on everyone that surrounded him. This style was very important for the thorough and professional training of a disciplined and successful Romanian army. This army, under his command, gained Romania's independence from both the Turks and the Russians.

After victory and the subsequent peace treaty, King Carol I raised the country's prestige with the Ottomans, Russia, and Western European countries, procured funding from Germany, arranged for Romania's first railway system, successfully boosted Romania's economy to unprecedented levels in its history, and also initiated the development of the very first Romanian sea fleet and navy with the port at ancient Tomis (Constantza). In the beginning, some of his efforts to encourage economical prosperity in Romania encountered strong opposition from a large section of his government, and in 1870, he even offered to abdicate if his leadership continued to be challenged to a stalemate by such Romanian political, dissenting factions and their continuous bickering. During his reign, Romania became the "agricultural supplier" of both Western Europe and Russia, exporting huge quantities of wheat and corn. It was the second largest exporter of cereal and the third of oil.[7] Carol also succeeded in rewarding with farmland many of the surviving Romanian veterans who had fought with him in Romania's Independence War.

Following his coronation on March 26, 1881, as the first King of Romanians, he firmly established a Hohenzollern-family based dynasty. His main purpose was to make his new, adopted country sustainable and permanent, well-integrated with Western Europe. King Carol I's true intent in establishing his dynasty was to allow the Romanian nation to exist free and independent of its militarily powerful neighbor states to the east and west, by preventing the former from reversing after his death what he had accomplished in his lifetime. By a rather strange (but perhaps meaningful) coincidence, his former Russian "ally" in the Independence War, the Czar (Tsar) Alexandr II Nykolaevich died, assassinated by the "russified" Polish-Lithuanian Ignacy Hryniewiecki—known as "Ignaty Grinevitzky," only two weeks before Carol coronation. The Tsar's assassination had been meant to ignite revolution in Russia, whereas in neighboring Romania, the crowning of its first, independent King was received with great enthusiasm by most Romanians, who were looking forward to a much brighter future as free, liberated descendants of an ancient people.

After leading Romania's (and also allied Russia's) armies to victory in its Independence War, King Carol I received repeatedly similar offers to rule over two other countries as well, Bulgaria and Spain, but he courteously declined such serious propositions as he saw these as a conflict of interest which he could not accept. In the Carpathian Mountains, he built Peleş Castle, still one of Romania's most visited touristic attractions. The castle was built in an external, German style, as a reminder of the King's origin, but its interior was, and is, decorated in various elegant styles, including art objects of neighboring nations, both East and West. After the Russo-Turkish war, Romania gained Dobruja and King Carol I ordered the first bridge over the Danube, between Feteşti and Cernavodă, linking the new acquired province to the rest of the country.

King Carol I left Romania a rich legacy, unprecedented in its entire history of more than a thousand years (claimed, in fact, by some historians to go as far back as two millennia to the established Roman Empire colony of Roman Dacia), which his follower at the throne, King Ferdinand I would build upon, to what was called before World War II, the "Greater Romania" (in Romanian: România Mare), that will also include the other three Romanian principalities of: Transylvania, Bukovina (Bucovina), and Bessarabia (Bassarabia—now the Republic of Moldova).

The end of the reign

The long rule of 48 years by King Carol I allowed both the rapid establishment and the strong economical development of the Romanian state. Towards the very end of his reign in 1913, and close to the start of the World War I, the German-born king was in favor of entering the war on the side of the Central Powers, whereas the majority of the Romanian public opinion sided with the Triple Entente because of the traditional, Romanian cultural (and historical) links with France. However, King Carol I had signed a secret treaty, in 1883, that linked Romania with the Triple Alliance (formed in 1882), and although the treaty was to be activated only in case of attack from Imperial Russia towards one of the treaty's members, Carol I thought that the honorable thing to do was to enter the war on the side of the German Empire. An emergency meeting was held with members of the government where the King told them about the secret treaty and shared his opinion with them. The strong disagreement that ensued is said by some to have brought on the 75-year old King's sudden death on October 10, 1914. The future King Ferdinand I, under the influence of his Parliament and also of his wife, Marie of Edinburgh, a British Princess, will be much more willing to listen to public opinion and join instead the Triple Entente treaty; as Carol I might have anticipated in his thorough considerations of the European balance of military power, King Ferdinand's decision resulted in several years of misery for the Romanian population, and also millions of Romanian soldiers dying in the war by fighting the very well-equipped German army; however, King Ferdinand's and his government's gamble surprisingly pay off when the Triple Entente finally won World War I, and the Greater Romania was established (with Transylvania joining Romania) under King Ferdinand I at the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919.

Life and family

When he was elected prince of Romania, Carol was not married and, according to the Romanian Constitution he himself had approved, he was not allowed to marry a woman of Romanian origin. In 1869, the prince started a trip around Europe and mainly Germany, to find a bride. During this trip he met and married at Neuwied on November 15, 1869, princess Elizabeth of Wied. Their marriage was said to be "one of the most unfitted matches" in history, with Carol being a "cold" and calculating man, whereas Elizabeth was a notorious dreamer and a poet at heart. They had only one child, Princess Maria, born in 1871, who died on March 24, 1874. This is said to have led to the further estrangement of the royal couple, Elizabeth never completely recovering from the trauma of losing her only child.

After the proclamation of the Kingdom of Romania in 1881, the succession became a very important matter of state. Since Carol I's brother, Leopold, and his oldest son, William, declined their rights to succession, the second son of Leopold, Ferdinand, was named Prince of Romania, and also heir to the throne. Elizabeth tried to influence the young Prince into marrying her favorite lady in waiting, Elena Văcărescu, but according to the Romanian Constitution the heir was forbidden from marrying any Romanian lady. As a result of her attempt, Elizabeth was exiled for two years, until Ferdinand's marriage to Princess Marie of Edinburgh.

Towards the end of their lives, though, Carol I and Elizabeth are said to have finally found a way to understand each other, and were reportedly to have become good friends. He died in his wife's arms.[8] He was buried in the Church at Curtea de Arges Monastery. His son, Ferdinand was king from 1914 until 1927.

Legacy

Under the 1866 Constitution (based on the that of Belgium), Carol had the right to "dissolve the legislature" and to appoint the Cabinet. Restrictions on the franchise based on income meant that the boyars, the traditional nobility "who were intent on maintaining their political and economic dominance."[9] Carol found himself acting as a "kind of arbiter between rival political factions."[10] He was skillful in managing the two-party system of Conservatives and Liberals.[11] These two parties alternated in power and when "he observed that a government was getting rusty, he summoned the opposition to power." In power, "the new government would organize elections, which it invariably won."[12] Yet, despite the boyars determination to retain their privileges, Carol has been credited with "developing democracy" as well as "education, industry, railways, and a strong army."[13]

In contrast, when Otto of Greece had become the first sovereign of the newly independent nation-state of Greece, also a foreigner invitee to the throne, Otto failed to nurture democracy, trying to rule Greece as an absolute monarchy. Otto also failed to fully embrace Greek culture, and remained "foreign." Carol made neither mistake; he fully embraced his adopted state and tried to emulate the developing constitutional monarchies of Western Europe. Unfortunately, his namesake and grandson, Carol II (king 1930-1940) saw democracy as "foreign" to Romania, and in the 1930s abrogated to the monarchy powers from parliament. In this, he parted company from Carol I and from his own father, Ferdinand.[14] This weakening of democracy prepared the ground for the growth of communism in Romania. After World War II, the monarchy was abolished and Romania joined the Soviet-bloc until 1989, when the communist regime collapsed. Carol I had a sense of duty towards his people. He wanted to lay solid foundations on which the new nation could build its economy, preserve freedom and secure a stable future. Carol has been compared with Michael the Brave because they both reunified Romania, although Carol's was no "fragile unification for one year but a reunification for all time."[15] Prior to Carol's reign, "there was a succession of revolutions, war, and foreign occupations." Subsequent to his reign "were two world wars, political instability, authoritarian regimes, more foreign occupation and, finally, the darkest years of Communism." Thus, the most "balanced" period of Romania's history "remains the 48-year reign of Carol I."[16] Now that Romania is once more free and democratic, it can once again celebrate Carol's legacy, which was excluded from the national consciousness by the Communist regime.[17]

Notes

- ↑ Lucian Boia and James Christian Brown, Romania: Borderland of Europe (London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2001, ISBN 9781861891037), 79.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 87.

- ↑ Sidney Whitman, Reminiscences of the King of Roumania (Palala Press, 2015, ISBN 1342610660), 16.

- ↑ Whitman, 18.

- ↑ Whitman, 31.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Whitman, 275.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 96-97.

- ↑ Julia P. Gelardi, Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 2005, ISBN 9780312324230), 204.

- ↑ Keith Hitchins, Rumania, 1866-1947 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1994, ISBN 9780585215105), 20.

- ↑ Hitchins, 21.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 103.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 90.

- ↑ Ellsworth Raymond and John Stuart Martin, A Picture History of Eastern Europe (New York, NY: Crown Publishers, 1971), 188.

- ↑ Steven D. Roper, Romania: The Unfinished Revolution (Amsterdam, NL: Harwood Academic, 2000, ISBN 9789058230287), 6.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 233.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 96.

- ↑ Boia and Brown, 233.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bobango, Gerald J. The Emergence of the Romanian National State. East European monographs, no. 58. Boulder, CO: East European Quarterly, 1979. ISBN 9780914710516.

- Boia, Lucian, and James Christian Brown. Romania: Borderland of Europe. Topographics. London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2001. ISBN 9781861891037.

- Gelardi, Julia P. Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 2005. ISBN 9780312324230.

- Hitchins, Keith. Rumania, 1866-1947. Oxford history of modern Europe. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1994. ISBN 9780585215105.

- Kellogg, Frederick. The Road to Romanian Independence. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1995. ISBN 9781557530653.

- Michelson, Paul E. Romanian Politics, 1859-1871: From Prince Cuza to Prince Carol. Iași, RO: Center for Romanian Studies, 1998. ISBN 9789739809191.

- Raymond, Ellsworth, and John Stuart Martin. A Picture History of Eastern Europe. New York, NY: Crown Publishers, 1971.

- Roper, Steven D. Romania: The Unfinished Revolution. Postcommunist states and nations. Amsterdam, NL: Harwood Academic, 2000. ISBN 9789058230287.

- Whitman, Sidney. Reminiscences of the King of Roumania. Palala Press, 2015. ISBN 1342610660

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.