Charlotte Corday

| Charlotte Corday | |

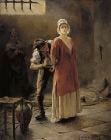

Charlotte Corday, painted at her request by Jean-Jacques Hauer, a few hours before her execution

| |

| Born | Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont 27 July 1768 Saint-Saturnin-des-Ligneries, Ăcorches, Normandy, France |

|---|---|

| Died | 17 July 1793 (aged 24) Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Known for | Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont (July 27, 1768 â July 17, 1793), known as Charlotte Corday (French pronunciation: [kÉÊdÉ]), was a figure of the French Revolution. A provincial woman who had supported the revolution and was a supporter of the Girondins, she became concerned over the course of the Revolution, particularly the purge of the Girondins. She devised a plan to assassinate Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who was in part responsible for the more radical course the Revolution had taken through his role as a politician and journalist.

In 1793, she was executed by guillotine for the assassination of Marat. His murder was depicted in the painting The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David, which shows Marat's dead body after Corday had stabbed him in his medicinal bath. In 1847, writer Alphonse de Lamartine gave Corday the posthumous nickname l'ange de l'assassinat (the Angel of Assassination).

Biography

Born in Saint-Saturnin-des-Ligneries, a hamlet in the commune of Ăcorches (Orne), in Normandy,[1] Charlotte Corday was a member of a minor aristocratic provincial family. She was a fifth-generation descendant of the dramatist Pierre Corneille. Her parents were cousins.

While Corday was a young girl, her older sister and their mother, Charlotte Marie Jacqueline Gaultier de Mesnival, died. Her father, Jacques François de Corday, Seigneur d'Armont (1737â1798), unable to cope with his grief over their deaths, sent Corday and her younger sister to the Abbaye aux Dames convent in Caen, where the former had access to the abbey's library and first encountered the writings of Plutarch, Rousseau and Voltaire. After 1791, she lived in Caen with her cousin, Madame Le Coustellier de Bretteville-Gouville. The two developed a close relationship, and Corday was the sole heir to her cousin's estate.[2]

Corday's physical appearance is described on her passport as "five feet and one inch ... hair and eyebrows auburn, eyes gray, forehead high, mouth medium size, chin dimpled, and an oval face".[3]

Politics

Corday was a supporter of the French Revolution. After the revolution radicalized further and headed towards terror, Charlotte Corday began to sympathize with the Girondins. The Girondins were known for their speeches, which she greatly admired. She had the chance to meet and interact with members of the Girondist groups while living in Caen. She respected the political principles of the Girondins and came to align herself with their thinking. She regarded them as a movement that would ultimately save France.[4] Like Corday, the Girondins were revolutionary republicans, but after the king was deposed and executed, favored a more moderate approach to the revolution. They were skeptical about the direction the revolution was taking. They were opposed to the more radical Montagnards. Members of the Montagnard faction espoused the view that the revolution could survive the invasion of European powers and civil war only through terrorizing and executing those opposed to it.[5]

Marat and the overthrow of the Girondins

After the execution of the king on January 21, 1793, a period of revolutionary infighting followed. From January to May, Jean-Paul Marat fought bitterly with the Girondins, whom he believed to be covert enemies of republicanism. Jean-Paul Marat was a member of the radical Jacobin faction that had a leading role during the Reign of Terror. As a journalist, he exerted power and influence through his newspaper, L'Ami du peuple ("The Friend of the People").[6]

Marat's hatred and suspicion of the Girondins became increasingly heated which led him to call for the use of violent tactics against them. The Girondins fought back and demanded that Marat be tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal. Marat was imprisoned, and on April 24, brought before the Tribunal on the charges that he had printed in his paper statements calling for widespread murder as well as the suspension of the Convention. In the midst of the failures in the civil war the Girondins were losing favor and overplayed their hand. Marat decisively defended his actions, stating that he had no evil intentions directed against the Convention. Marat was acquitted of all charges to the riotous celebrations of his supporters.

In response, Marat helped to engineer an insurrection against the Girondins in the National Convention. The Insurrection of May 31 - June 2 deposed the Girondins from power. 22 of their leaders were indicted. Some were arrested. Others fled to the countryside, some to Caen. Marat's role in helping to organize the arrests were well-known. The presence of the escaped Girondins in her town in the midst of the drama helped to galvanize her decision. In Caen, Corday followed these events with horror, asking the question, "Shall I or shall I not?"[7]

The Die is Cast

The indictment of the Girondins and the flight of some of them to Caen seems to have helped her make up her mind. She would act to save the nation. The influence of Girondin ideas on Corday is evident in her words at her trial: "I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand."[8] As the revolution progressed, the Girondins had become progressively more opposed to the radical, violent propositions of the Montagnards such as Marat and Robespierre. Corday's notion that she was saving a hundred thousand lives echoes this Girondin sentiment as they attempted to slow the revolution and reverse the violence that had escalated since the September Massacres of 1792.[9]

Corday's decision to kill Marat was stimulated not only by her revulsion at the September Massacres, for which she held Marat responsible, but by her fear of an all-out civil war. She believed that Marat was threatening the Republic, and that his death would end violence throughout the country. She also believed that King Louis XVI should not have been executed.[10]

On July 9, 1793, Corday left her cousin, carrying a copy of Plutarch's Parallel Lives, and went to Paris, where she took a room at the HÎtel de Providence. (The Hotel was at 19 rue des Vieux Augustins, now rue d'Argout.) She bought a kitchen knife with a 6-inch (15 cm) blade. During the next few days, she wrote her Adresse aux Français amis des lois et de la paix ("Address to the French, friends of Law and Peace") to explain her motives for assassinating Marat.[11]

Marat's assassination

Corday initially planned to assassinate Marat in front of the entire National Convention "in full view of the 'representatives of the nation.'"[12] She intended to make an example of him, but upon arriving in Paris she discovered that Marat no longer attended meetings because his health was deteriorating due to a skin disorder (perhaps dermatitis herpetiformis). She was then forced to change her plan. She went to Marat's home before noon on July 13, claiming to have knowledge of a planned Girondist uprising in Caen; she was turned away by Catherine Evrard, the sister of Marat's fiancée, Simonne.[13]

On her return that evening, Marat admitted her. At the time, he conducted most of his affairs from a bathtub because of his skin condition. Marat wrote down the names of the Girondins that she gave to him; she then pulled out the knife and plunged it into his chest. He called out: Aidez-moi, ma chĂšre amie! ("Help me, my dear friend!"), and then died.[14]

This is the moment memorialized by Jacques-Louis David's painting The Death of Marat. A different angle of the iconic pose of Marat dead in his bath is in Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry's 1860 painting Charlotte Corday.

In response to Marat's dying shout, Simonne Evrard rushed into the room. She was joined by a distributor of Marat's newspaper, who seized Corday. Two neighbors, a military surgeon and a dentist, attempted to revive Marat. Republican officials arrived to interrogate Corday, and to calm a hysterical crowd who appeared ready to lynch her.[15]

Trial

Corday underwent three separate cross-examinations by senior revolutionary judicial officials, including the President of the Revolutionary Tribunal and the chief prosecutor. She stressed that she was a republican and had been so even before the Revolution, citing the values of ancient Rome as an ideal model.[16]

The focus of the questioning was to establish whether she had been part of a wider Girondist conspiracy. Corday remained constant in insisting that "I alone conceived the plan and executed it." She referred to Marat as a "hoarder" and a "monster" who was respected only in Paris. She credited her fatal knifing of Marat with one blow not to practicing in advance but to luck.[17]

Charlotte Corday asked for Gustave le Doulcet, an old acquaintance, to defend her, but he did not receive the letter she wrote to him in time, so Claude François Chauveau-Lagarde was appointed instead to assist her during the trial.[18] It is believed that Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville voluntarily delayed the letter,[19] however, Corday thought that Le Doulcet refused to defend her and sent to him a last letter of reproach just before going to the scaffold.

Charlotte Corday sent the following farewell letter to her father which was intercepted and read during the trial:

Forgive me, my dear papa, for having disposed of my existence without your permission. I have avenged many innocent victims, I have prevented many other disasters. The people, one day disillusioned, will rejoice in being delivered from a tyrant. If I tried to persuade you that I was passing through England, it was because I hoped to keep it incognito, but I recognized the impossibility. I hope you will not be tormented. In any case, I believe that you would have defenders in Caen. I took Gustave Doulcet as a defender: such an attack allows no defense, it's for the form. Goodbye, my dear papa, please forget me, or rather rejoice in my fate, the cause is good. I kiss my sister whom I love with all my heart, as well as all my parents. Do not forget this verse by Corneille:      Crime is shame, not the scaffold!

It is tomorrow at eight o'clock that I am judged. This 16 July.[20]

Execution

Following her sentencing Corday asked the court if her portrait could be painted, purportedly to record her true self. She made her request pleading, "Since I still have a few moments to live, might I hope, citizens, that you will allow me to have myself painted."[21] Given permission, she selected as the artist a National Guard officer, Jean-Jacques Hauer, who had already begun sketching her from the gallery of the courtroom. Hauer's likeness was completed shortly before Corday was summoned to the tumbril, after she had viewed it and suggested a few changes.[22]

Since her execution, many authors have written describing Corday as a natural blonde, primarily due to this portrait by Hauer. Although Hauer admired her and took a keen interest in her fate, he had to depict Corday as a vain aristocrat and counterrevolutionary for his own protection. To give the idea that she had taken the time to make herself presentable and powder her hair before murdering Marat, Hauer painted Corday's hair a very light shade. Despite the fame of this one portrait, many other paintings (done both in life and posthumously) show Corday in her true brunette form, and her passport describes her hair as "chestnut" (chĂątains), refuting the idea that Corday had fair hair.[23]

On July 17, 1793, four days after Marat was killed, Corday was executed by the guillotine in the Place de GrĂšve wearing the red overblouse denoting a condemned traitor who had assassinated a representative of the people. Standing alone in the tumbril amid a large and curious crowd she remained calm, although drenched by a sudden summer rainfall.[24] Her body was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery.[25] According to legend, her skull was said to have been removed from her grave and passed from person to person in later years.[26]

Aftermath

After Corday's decapitation, a man named Legros lifted her head from the basket and slapped it on the cheek. Charles-Henri Sanson, the executioner, indignantly rejected published reports that Legros was one of his assistants. Sanson stated in his diary that Legros was in fact a carpenter who had been hired to make repairs to the guillotine.[27] Witnesses report an expression of "unequivocal indignation" on her face when her cheek was slapped. The oft-repeated anecdote has served to suggest that victims of the guillotine may in fact retain consciousness for a short while, including by Albert Camus in his Reflections on the Guillotine. ("Charlotte Corday's severed head blushed, it is said, under the executioner's slap.").[28]

This offense against a woman executed moments before was considered unacceptable and Legros was imprisoned for three months because of his outburst.[29]

Jacobin leaders had her body autopsied immediately after her death to see if she was a virgin. They believed there was a man sharing her bed and the assassination plans. To their dismay, she was found to be a virgin.[30]

| French (Original) | English (Translation) |

|---|---|

| La vertu seule est libre. Honneur de notre histoire,

Notre immortel opprobre y vit avec ta gloire, Seule tu fus un homme, et vengeas les humains. Et nous, eunuques vils, troupeau lùche sans ùme, Nous savons répéter quelques plaintes de femme, Mais le fer pÚserait à nos dÚbiles mains. |

Virtue alone is free. Honor of our history,

Our immortal opprobrium lives there with your glory, Only you were a man, and avenged the humans. And we, vile eunuchs, a cowardly herd without a soul, We know how to repeat a few complaints from a woman, But the iron would be heavy in our feeble hands. |

Legacy

The direct consequences of her crime were the exact opposite to what she expected. The assassination did not stop the Jacobins or the Terror; it accelerated it. The murder of one of their colleagues only intensified their efforts and the work of the Revolutionary Tribunal.[31] It also turned Marat into a martyr of the revolution. A bust of him replaced a religious statue on the rue aux Ours and a number of place-names were changed to honor Marat.[32]

The Revolution and women

Corday's act transformed the perception of what a woman was capable of doing, and to those who did not shun her for her act, she became a heroine. André Chénier wrote a poem in honor of Corday. This highlighted the "masculinity" possessed by Corday during the revolution.[33] Corday's killing of Marat was considered vile, an "arch-typically masculine statement." This reaction showed that whether or not one approved of what she did, it is clear that the murder of Marat changed the political role and position of women during the French Revolution.[34] Corday was surprised by the reaction of revolutionary women, stating, "As I was truly calm I suffered from the shouts of a few women. But to save your country means not noticing what it costs."[35]

Corday's action aided in restructuring the private versus public role of the woman in society at the time. The idea of women as second class or "less than" was challenged, and Corday was considered a hero to those who were against the teachings of Marat. There have been suggestions that her act incited the banning of women's political clubs, and the executions of female activists such as the Girondin Madame Roland.[36]

Cultural references

Corday's act was fertile soil for the imagination of artists in many different genres. There are dozens of representation. Among the best known, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote about her in his Posthumous Fragments of Margaret Nicholson (1810).[37] Alphonse de Lamartine devoted a book of his Histoire des Girondins series (1847) to her, giving her this now-famous nickname: "l'ange de l'assassinat" (the angel of assassination).[38] French dramatist François Ponsard wrote a play, Charlotte Corday, that was premiÚred at the Théùtre-Français in March 1850.[39] In Victor Hugo's 1862 novel Les Misérables, Combeferre likens Enjolras's execution of Le Cabuc to Corday's assassination of Marat, calling it a "liberating murder".[40] Harper's Weekly mentioned Corday in their 29 April 1865 edition, in a series of articles analyzing the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, as the "one assassin whom history mentions with toleration and even applause," but goes on to conclude that her assassination of Marat was a mistake in that she became Marat's victim rather than saving or helping his victims.[41] At the end of Act III, before departing to kill the Czar, the eponymous heroine of Oscar Wilde's play Vera; or, The Nihilists (1880) exclaims "the spirit of Charlotte Corday has entered my soul now."[42] In the 1903 novel Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, young Rebecca re-enacts a scene of Charlotte Corday in prison, with her friends playing the role of the mob.[43] In Peter Weiss's 1963 Marat/Sade, the assassination of Marat is presented as a play, written by the Marquis de Sade, to be performed for the public by inmates of the asylum at Charenton.[44]

Gallery

Detail from The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David. Marat's dead hand grips a piece of bloody paper which reads, "July 13, 1793. Marie Anne Charlotte Corday to Citizen Marat. Suffice it to say that I am very unhappy to be entitled to your benevolence."

Notes

- â "Document du baptĂȘme de Charlotte Corday,", 1768, Archives et patrimoine culturel de l'Orne, 36. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- â John Mills Whitham, Men and Women of the French Revolution (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1968), 154-157.

- â Augustin CabanĂšs, "Curious Bypaths of History: Being Medico-historical Studies and Observations," C. Carrington, 1898, 352. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- â Marie Cher, Charlotte Corday and Certain Men of the Revolutionary Torment (New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1929, ISBN 1436683548), 70

- â David Andress, The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006, ISBN 978-0374530730),

- â Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989, ISBN 978-0394559483), 445.

- â Stanley Loomis, Paris in the Terror: June 1793-July 1794 (Philadelphia, PA and New York, NY: J. B. Lippincott, 1964), 13.

- â John Herbert Clifford, The Standard History of the World, volume 6 University society Incorporated, 1907. 3382. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- â Loomis, 140-145.

- â Whitham, 160-161.

- â Richard Cobb, The French Revolution. Voices From A Momentous Epoch (London, UK: Guild Publishing, 1988, ISBN 978-0671699253), 192.

- â Schama, 735.

- â Schama, 735.

- â Schama, 736.

- â Schama, 737.

- â Cobb, 192-193.

- â Schama, 736â37.

- â "13 juillet 1793Â : Charlotte Corday assassine le citoyen Marat dans sa baignoire," Le Figaro, July 12, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- â "Le procĂšs de Charlotte Corday," French Ministry of Justice, August 23, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- â Pardonnez-moi, mon cher papa, dâavoir disposĂ© de mon existence sans votre permission. Jâai vengĂ© bien dâinnocentes victimes, jâai prĂ©venu bien dâautres dĂ©sastres. Le peuple, un jour dĂ©sabusĂ©, se rĂ©jouira dâĂȘtre dĂ©livrĂ© dâun tyran. Si jâai cherchĂ© Ă vous persuader que je passais en Angleterre, câest que jâespĂ©rais garder lâincognito, mais jâen ai reconnu lâimpossibilitĂ©. JâespĂšre que vous ne serez point tourmentĂ©. En tout cas, je crois que vous auriez des dĂ©fenseurs Ă Caen. Jâai pris pour dĂ©fenseur Gustave Doulcet : un tel attentat ne permet nulle dĂ©fense, câest pour la forme. Adieu, mon cher papa, je vous prie de mâoublier, ou plutĂŽt de vous rĂ©jouir de mon sort, la cause en est belle. Jâembrasse ma sĆur que jâaime de tout mon cĆur, ainsi que tous mes parents. Nâoubliez pas ce vers de Corneille:

Le Crime fait la honte, et non-pas lâĂ©chafaud !

Câest demain Ă huit heures, quâon me juge. Ce 16 juillet. - â Chantal Thomas, "Heroism in the Feminine: The Examples of Charlotte Corday and Madame Roland," The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation 30(2), University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989, 75.

- â Schama, 740â741.

- â "The Blonding of Charlotte Corday," ResearchGate Eighteenth-Century Studies 38(1), January 2004, 201-221. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- â Schama, 741.

- â Loomis, 147.

- â "Charlotte Corday's Head and Tales of What Happened," geriwalton.com July 27, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- â Charles-Henri Sanson, La RĂ©volution française vue par son bourreau : Journal de Charles-Henri Sanson (Paris, FR: Le Cherche Midi, 2007, 978-2749109305), 65.

- â Arthur Koestler and Albert Camus, Reflexions sur la peine Capitale (Calmann-Levy, 2002, ISBN 978-2070418466), 139.

- â François Mignet, History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814 1824, (New York, NY: Wentworth Press, Inc., 2019, ISBN 978-0469182769).

- â Catherine R. Montfort (ed.), Literate Women and the French Revolution of 1789 (Birmingham, AL: Summa Publications, 1994, ISBN 978-1883479077), 45.

- â "Le procĂšs de Charlotte Corday," French Ministry of Justice, August 23, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- â Schama, 745.

- â Chantal, 75-76.

- â Elizabeth R. Kindleberger, "Charlotte Corday in Text and Image: A Case Study in the French Revolution and Women's History," French Historical Studies 18(4), 1994, 969â999.

- â M. ChĂ©ron de Villiers, "Charlotte Corday," Revue contemporaine," volume 79, 1865, 618. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- â Elizabeth Kindleberger, "Charlotte Corday in Text and Image: A Case Study in the French Revolution and Women's History," French Historical Studies 18(4), 1994, 973.

- â Percy Bysshe Shelley and Thomas Jefferson Hogg, "Posthumous fragments of Margaret Nicholson; being poems found amongst the papers of that noted female who attempted the life of the king in 1786," Oxford, UK: J. Munday, 1810, 11-17. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- â Alphonse de Lamartine, Histoire de Charlotte Corday: un livre de l'Histoire des Girondins trans. History of Charlotte Corday: A book of the History of the Girondins (Paris, FR: Editions Champ Vallon, 1995, ISBN 978-2876732025), 13.

- â François Posnard, "Charlotte Corday: A Tragedy," TrĂŒbner and Company, 1867, 7. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- â Victor Hugo, Les Miserables trans. Lee Fahnestock & Norman MacAfee, (New York, NY: Signet Classics, 1987, ISBN 978-0451419439), 1175.

- â Harper's Weekly: Volume 9 for the Year 1865, Harper's Magazine Company, 1865, 278. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- â Oscar Wilde, The Writings of Oscar Wilde: Salome; The duchess of Padua; Vera, or, The nihilists, Keller-Farmer, 1907, 400. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- â Kate Douglas Wiggins, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (New York, NY: Golden Illustrated, 1903), 62.

- â Peter Weiss and Geoffrey Skelton, Marat/Sade (London, UK: Marion Boyars Publishing, 1969, ISBN 978-0714503615)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. ISBN 978-0374530730

- Cher, Marie. Charlotte Corday and Certain Men of the Revolutionary Torment. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1929. ISBN 1436683548

- Cobb, Richard. The French Revolution. Voices From A Momentous Epoch. London, UK: Guild Publishing, 1988. ISBN 978-0671699253

- Hugo, Victor. trans. Lee Fahnestock and Norman MacAfee. Les Miserables. New York, NY: Signet Classics, 1987. ISBN 978-0451419439

- Kindleberger, Elizabeth. "Charlotte Corday in Text and Image: A Case Study in the French Revolution and Women's History," French Historical Studies 18(4), 1994.

- Koestler, Arthur, and Albert Camus. Reflexions sur la peine Capitale. Calmann-Levy, 2002. ISBN 978-2070418466

- Lamartine, Alphonse de. Histoire de Charlotte Corday: un livre de l'Histoire des Girondins (History of Charlotte Corday: A book of the History of the Girondins). Paris, FR: Editions Champ Vallon, 1995. ISBN 978-2876732025

- Loomis, Stanley. Paris in the Terror. New York, NY: Dorset House Publishing Co., Inc., 1990. ISBN 978-0880294010

- Montfort, Catherine R. (ed.). Literate Women and the French Revolution of 1789. Birmingham, AL: Summa Publications, 1994. ISBN 978-1883479077

- Mignet, François. History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814 1824. New York, NY: Wentworth Press, Inc., 2019. ISBN 978-0469182769

- Sanson, Charles-Henri. La Révolution française vue par son bourreau : Journal de Charles-Henri Sanson. Paris, FR: Le Cherche Midi, 2007. 978-2749109305

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. ISBN 978-0394559483

- Thomas, Chantal. "Heroism in the Feminine: The Examples of Charlotte Corday and Madame Roland," The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation 30(2), University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989. 67-82.

- Weiss, Peter, and Geoffrey Skelton. Marat/Sade. London, UK: Marion Boyars Publishing, 1969. ISBN 978-0714503615

- Whitham, John Mills. Men and Women of the French Revolution. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1968.

- Wiggins, Kate Douglas. Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. Signet Classics, 1991 (original 1903). ISBN 978-0451524836

Further reading

- Alstine, RK van. Charlotte Corday. Kellock Robertson Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1409796589

- Franklin, Charles. Woman in the Case. New York, NY: Taplinger, 1968. ISBN 978-0800884253

- Gutwirth, Madelyn, The Twilight of the Goddesses; Women and Representation in the French Revolutionary Era. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780813517872

- Mazeau, Guillaume. Le bain de l'histoire. Charlotte Corday et l'attentat contre Marat (1793â2009). Champ Vallon, FR: Seyssel, 2009. ISBN 978-2876735019

- Mazeau, Guillaume. Corday contre Marat. Deux siĂšcles d'images. Versailles, FR: Artlys, 2009. ISBN 2854953770

- Mazeau, Guillaume. Charlotte Corday en 30 Questions. Paris, FR: Geste Ă©ditions, 2006. ISBN 978-2845612839

- Outram, Dorinda. The Body and the French Revolution: Sex, Class and Political Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0300044362

- Sokolnikova, Halina. Nine Women Drawn from the Epoch of the French Revolution trans. H C Stevens. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0548140475

External links

All links retrieved December 4, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.