Courtly Love

Courtly love was a medieval European conception of ennobling love which found its genesis in the ducal and princely courts in regions of present-day southern France at the end of the eleventh century. It involved a paradoxical tension between erotic desire and spiritual attainment, "a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and self-disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent."[1] It can be seen as a combination of complex factors: Philosophical, social, religious, romantic, and erotic.

The terms used for courtly love during the medieval period itself were "Amour Honestus" (Honest Love) and "Fin Amor" (Refined Love). The term "courtly love" was first popularized by Gaston Paris in 1883, and has since come under a wide variety of definitions.

The French court of the troubadour Duke William IX was an early center of the culture of courtly love. William's granddaughter, Eleanor of Aquitaine, was a great influence in spreading this culture. She supported the ideals of courtly love throughout her reign in Aquitaine and brought it to England when she married Henry II. Her daughter, Marie of Champagne, encouraged Chrétien de Troyes to write Lancelot. Later, the ideas of courtly love were formally expressed in a three part treatise by André le Chapelain. In the thirteenth century, the lengthy poem, Roman de la rose, painted the image of a lover suspended between happiness and despair.

Scholars have debated the degree to which courtly love was practiced in the real world versus being a literary ideal, as well as whether its literature was meant to represent a sexual relationship or a spiritual one, using erotic language allegorically.

Origin of term

The term amour courtois ("courtly love") was given its original definition by Gaston Paris in his 1883 article, "Ătudes sur les romans de la Table Ronde: Lancelot du Lac, II: Le conte de la charrette," a treatise inspecting Chretien de Troyes's Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart (1177). Paris defined amour courtois as involving both idolization and an ennobling discipline. The lover (idolizer) accepts the independence of his mistress and tries to make himself worthy of her by acting bravely and honorably and by doing whatever deeds she might desire. Sexual satisfaction may not have been either a goal or the end result. However, courtly love was not always entirely Platonic either, as it was based on attraction, which sometimes involved strong sexual feelings.

Both the term and Paris's definition of it were soon widely accepted and adopted. In 1936, C.S. Lewis wrote the influential book, The Allegory of Love, further solidifying courtly love as "love of a highly specialized sort, whose characteristics may be enumerated as Humility, Courtesy, Adultery, and the Religion of Love."[2] Later, historians such as D.W. Robertson[3] in the 1960s, and John C. Moore[4] and E. Talbot Donaldson[5] in the 1970s, were critical of the term as being a modern invention.

History

Courtly love had its origins in the castle life of four regions: Aquitaine, Provence, Champagne, and ducal Burgundy, beginning about the time of the First Crusade (1099). It found its early expression in the lyric poems written by troubadours, such as William IX, Duke of Aquitaine (1071-1126), one of the first troubadour poets.

Poets adopted the terminology of feudalism, declaring themselves the vassal of the lady and addressing her as midons (my lord). The troubadour's model of the ideal lady was the wife of his employer or lord, a lady of higher status, usually the rich and powerful female head of the castle. When her husband was away on a Crusade or other business, and sometimes while he remained at home, she dominated the household and especially its cultural affairs. The poet gave voice to the aspirations of the courtier class, for only those who were noble could engage in courtly love. This new kind of love, however, saw true nobility as being based on character and actions, not wealth and family history, thus appealing to poorer knights who hoped for an avenue for advancement.

Eleanor of Aquitaine, William IX's granddaughter who was queen to two kings, brought the ideals of courtly love from Aquitaine first to the court of France, then to England. Eleanor enjoyed fame for her beauty and character, and troubadours wrote songs about her, "If all the world were mine from the seashore to the Rhine, that price were not too high to have England's Queen lie close in my my arms."[6] Her daughter, Marie, Countess of Champagne, brought the tradition to the Count of Champagne's court. The rules of courtly love were codified by the late twelfth century in Andreas Capellanus' influential work De Amore (Concerning Love).

Stages of courtly love

The following stages of courtly love were identified by scholar Barbara Tuchman from her studies of medieval literature. However, not all stages are present in every account of romantic love, and the question of how literally some of the stages should be taken is a point of controversy.[7]

- Attraction to the lady, usually via eyes/glance

- Worship of the lady from afar

- Declaration of passionate devotion

- Virtuous rejection by the lady

- Renewed wooing with oaths of virtue and eternal fealty

- Moans of approaching death from unsatisfied desire (and other physical manifestations of lovesickness)

- Heroic deeds of valor which win the lady's heart

- Consummation of the secret love

- Endless adventures and subterfuges avoiding detection

Impact

Courtly love had a civilizing effect on knightly behavior. The prevalence of arranged marriagesâoften involving young girls to older men for strictly political purposesâmotivated other outlets for the expression of personal love. At times, the lady could be a princesse lointaine, a far-away princess, and some tales told of men who had fallen in love with women whom they had never seen, merely on hearing their perfection described. Normally, however, she was not so distant. As the etiquette of courtly love became more complicated, the knight might wear the colors of his lady: Blue or black were the colors of faithfulness; green was a sign of unfaithfulness. Salvation, previously found in the hands of the priesthood, now came from the hands of one's lady. In some cases, there were also female troubadours who expressed the same sentiment for men.

Courtly love thus saw a woman as an ennobling spiritual and moral force, a view that was in opposition to medieval ecclesiastical sexual attitudes. Rather than being critical of romantic love as sinful, the poets praised it as the highest ideal.

The ideals of courtly love would impact on Church traditions in important ways. Marriage had been declared a sacrament of the Church, at the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215, and within Christian marriage, the only purpose was procreation with any sex beyond that purpose seen as non-pious. The ideal state of a Christian was celibacy, even in marriage. By the beginning of the thirteenth century, the ideas of courtly tradition were condemned by the church as being heretical. However, the Church channeled many of these romantic energies into veneration of the cult of the Virgin.

It is not a coincidence that the cult of the Virgin Mary began in the twelfth century as a counter to the secular, courtly, and lustful views of women. Bernard of Clairvaux was instrumental in this movement, and Francis of Assisi would refer to both chastity and poverty as "my Lady."

Literary conventions

The literary conventions of courtly love are evident in most of the major authors of the Middle Ages, such as Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, Dante, Marie de France, Chretien de Troyes, Gottfried von Strassburg, and Malory. The medieval genres in which courtly love conventions can be found include lyric poetry, the Romance, and the allegory.

Lyric Poety: The concept of courtly love was born in the tradition of lyric poetry, first appearing with Provençal poets in the eleventh century, including itinerant and courtly minstrels such as the French troubadours and trouveres. This French tradition spread later to the German MinnesÀnger, such as Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach.

Romance: The vernacular court poetry of the romans courtois, or Romances, saw many examples of courtly love. Many of them are set within the cycle of poems celebrating King Arthur's court. This was a literature of leisure, directed to a largely female audience for the first time in European history.

Allegory: Medieval allegory also shows elements of the tradition of courtly love. A prime example of this is the first part of The Romance of the Rose.

More formal expressions of the concept also appeared. Perhaps the most important and popular work of courtly love was that of Andreas Capellanus's De Amore, which described the ars amandi ("the art of loving") in twelfth century Provence. His work followed in the tradition of the Roman work Ars amatoria ("Art of Love") by Ovid, and the Muslim work Tawq al-hamamah (The Turtle-Dove's Necklace) by Ibn Hazm.

The themes of courtly love were not confined to the medieval, but are seen both in serious and comic forms in Elizabethan times.

Points of controversy

Sexuality

Within the corpus of troubadour poems there is a wide range of attitudes, even across the works of individual poets. Some poems are physically sensual, even bawdily imagining nude embraces, while others are highly spiritual and border on the platonic.[8]

A point of ongoing controversy about courtly love is to what extent it was sexual. All courtly love was erotic to some degree and not purely platonic. The troubadours speak of the physical beauty of their ladies and the feelings and desires the ladies rouse in them. It is unclear, however, what a poet should do about these feelingsâlive a life of perpetual desire channeling his energies to higher ends, or strive for physical consummation of his desire.

The view of twentieth century scholar Denis de Rougemont is that the troubadours were influenced by Cathar doctrines which rejected the pleasures of the flesh and that they were addressing the spirit and soul of their ladies using the metaphorical language of eroticism.[9] Edmund Reiss agreed that courtly love was basically spiritual, arguing that it had more in common with Christian love, or caritas, than the gnostic spirituality of the Cathars.[10] On the other hand, scholars such as Mosché Lazar hold that courtly love was outright adulterous sexual love with physical possession of the lady the desired end.[11]

Origins

Many of the conventions of courtly love can be traced to Ovid, but it is doubtful that they are all traceable to this origin. The Arabist hypothesis, proposes that the ideas of courtly love were already prevalent in Al-Andalus and elsewhere in the Islamic world, before they appeared in Christian Europe.

According to this theory, in eleventh century Spain, Muslim wandering poets would go from court to court, and sometimes travel to Christian courts in southern France, a situation closely mirroring what would happen in southern France about a century later. Contacts between these Spanish poets and the French troubadours were frequent. The metrical forms used by the Spanish poets were similar to those later used by the troubadours. Moreover, the First Crusade and the ongoing Reconquista in Spain could easily have provided opportunities for these ideas to make their way from the Muslim world to Christendom.

Real-world practice

A continued point of controversy is whether courtly love was primarily a literary phenomenon or was actually practiced in real life. Historian John Benton found no documentary evidence for courtly love in law codes, court cases, chronicles or other historical documents.[12] However, the existence of the non-fiction genre of courtesy books may provide evidence for its practice. For example, the Book of the Three Virtues by Christine de Pizan (c. 1405), expresses disapproval of the ideal of courtly love being used to justify and cover-up illicit love affairs. Courtly love also seems to have found practical expression in customs such as the crowning of Queens of Love and Beauty at tournaments.

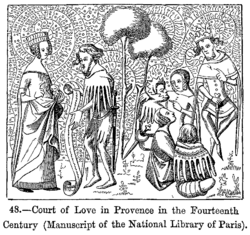

Courts of love

Another issue is the alleged existence of "courts of love," first mentioned by Andreas Capellanus in the twelfth century. These were supposed courts made up of tribunals staffed by ten to 70 women who would hear a case of love and judge it based on the rules of love. Nineteenth century historians took the existence of these courts as fact. However later historians such as John F. Benton noted "none of the abundant letters, chronicles, songs and pious dedications" suggest they ever existed outside of the poetic literature.[13] According to Diane Bornstein, one way to reconcile the differences between the references to courts of love in the literature and the lack of documentary evidence in real life, is that they were like literary salons or social gatherings, where people read poems, debated questions of love, and played word games of flirtation.[14]

Notes

- â Francis X. Newman, The Meaning of Courtly Love. (1968).

- â C.S. Lewis, The Allegory of Love (1985).

- â D.W. Robertson. A Preface to Chaucer: Studies in Medieval Perspectives (1962).

- â John C. Moore, "Courtly Love: A Problem of Terminology," Journal of the History of Ideas 40.4 (1979): 621-632.

- â E. Talbot Donaldson. "The Myth of Courtly Love," in Speaking of Chaucer (1970).

- â Bonnie Wheeler, Medieval Heroines in History and Legend (2002).

- â Barbara Wertheim Tuchman, A Distant Mirror (1978).

- â Diane Bornstein, "Courtly Love," in Dictionary of the Middle Ages (1986), p. 668-674.

- â Denis de Rougemont, Love in the Western World (1956).

- â Edmund Reiss, "Fin'amors: Its History and Meaning in Medieval Literature" in Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies (1979), p. 8.

- â MoschĂ© Lazar, Amour courtois et "fin'amors" dans le littĂ©rature du XII siĂšcle (1986).

- â John F. Benton, Studies in Philology and Speculum (1962 and 1961).

- â Ibid.

- â Diane Bornstein, 1986.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benton, John F. "The Evidence for Andreas Capellanus Re-examined Again." In Studies in Philology, 59 (1962).

- Capellanus, Andreas. The Art of Courtly Love. Columbia University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0231073059

- Duby, Georges. The Knight, the Lady, and the Priest: the Making of Modern Marriage in Medieval France. Translated by Barbara Bray. Pantheon Books, 1983.

- Lewis, C.S. The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition. Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0192812203

- Markale, Jean. Courtly Love: The Path of Sexual Initiation. Inner Traditions, 2000. ISBN 978-0892817719

- Menocal, Maria Rosa. The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990. ISBN 0812213246

- Moore, John C. "Courtly Love: A Problem of Terminology." Journal of the History of Ideas. 40(4) (October, 1979).

- Newman, Francis X. The Meaning of Courtly Love. State University of New York Press, 1968.

- Robertson, Durant W. A Preface to Chaucer: Studies in Medieval Perspectives. Princeton Univ Press, 1962. ISBN 978-0691012940

- Schultz, James A. Courtly Love, the Love of Courtliness, and the History of Sexuality. The University of Chicago Press, 2006. ISBN 0226740897

- Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim. A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous 14th Century. Knopf, 1978. ISBN 0394400267

- Wheeler, Bonnie. Medieval Heroines in History and Legend, part II. The Teaching Company, 2002. ISBN 1565855248

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2024.

- Courtly Love, Washington State University. www.wsu.edu.

- Courtly love, Encyclopedia Britannica Online. www.britannica.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.