| Dengue virus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A TEM micrograph showing dengue virus

| ||||||||

| Virus classification | ||||||||

|

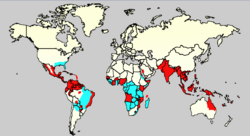

Dengue fever is an acute febrile disease caused by one of several closely related viruses transmitted to humans by mosquitoes, and characterized by high fever (which reoccurs after a pause), headache, chills, eye pain, rash, and extreme muscle and joint pain. It is found in warm environments in the Americas, Africa, Middle East, and southeast Asia. Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) is a more severe illness that occurs when someone is reinfected with the virus after having recovered from an earlier incidence of dengue fever and the immune system overreacts (Carson-DeWitt 2004). Dengue shock syndrome (DSS) is largely a complication of DHF (Pham et al. 2007). Dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS) is a leading cause of hospitalization and death among children in several south-east Asian nations (Kouri et al. 1989).

World Health Organization estimates that there may be 50 million cases of dengue infection worldwide each year (WHO 2008).

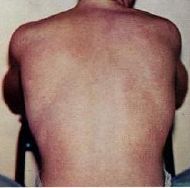

The typical rash seen in dengue fever | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | A90 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 061 |

| OMIM | 614371 |

| MedlinePlus | 001374 |

| eMedicine | med/528 |

| DiseasesDB | 3564 |

Although there presently is no vaccine, dengue fever is a preventable disease, involving aspects of both social and personal responsibility. As the illness is spread by mosquitoes, one preventive measure is to decrease the mosquito population, whether community-wide efforts or individuals getting rid of standing water in buckets, vases, and so forth (where mosquitoes breed). Another preventive measure is to use means to repel the mosquitoes, such as with insect repellents or mosquito nets.

Overview

Dengue fever is caused by four closely related virus serotypes of the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae (CDC 2008). Each serotype is sufficiently different that there is no cross-protection and epidemics caused by multiple serotypes (hyperendemicity) can occur. In addition to the dengue virus, Flaviviridae includes hepatitis C, West Nile, and yellow fever viruses.

The dengue type of virus is known as an arbovirus, arthropod-borne virus, because it is transmitted by mosquitoes, a type of arthropod. It is transmitted generally by Aedes aegypti (rarely Aedes albopictus). The disease cannot be transmitted from person to person directly, as with the influenza, but requires this intermediate vector to carry the virus from host to host.

After entering the body, the virus travels to various organs and multiplies, and then can enter the bloodstream. The presence of the virus within the blood vessels results in their swelling and leaking, as well as the enlargement of the spleen and lymph nodes, and the death of patches of liver tissue. There is a risk of severe bleeding (hemorrhage) (Carson-DeWitt 2004).

Between transmission to a person and the first appearance of symptoms, there is an incubation period of about five to eight days when the virus multiplies. Symptoms then appear suddenly, such as high fever, headache, enlarged lymph nodes, and severe pain in the legs and joints. It is a biphasic illness. After an initial period of illness of about two to three days, the fever drops rapidly and the patient will feel somewhat well for a brief period of perhaps a day. Then symptoms return, including a fever (although lesser in temperature), and a rash, as well as other symptoms (Carson-Dewitt 2004). The severe pain associated with dengue fever has lead to it also being called break-bone fever or bonecrusher disease.

Once infected, the immune system produces cell preventing infection with that particular strain of virus for about a year. However, if a person had dengue fever and recovered, but then was reinfected, the immune system overreacts and one gets a severe form of illness called dengue hemoohagic fever (DHF) or dengue shock syndrome (DSS). There is significant evidence that this disease is most common when the reinfection is with another strain different from the original infection.

Dengue is found in Central and South America and the Caribbean Islands, Africa, Middle East, and east Asia. The geographical spread of dengue fever is similar to malaria, but unlike malaria, dengue is often found in urban areas of tropical nations, including Trinidad and Tobago Puerto Rico, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, India, Brazil and Venezuela. It only rarely occurs in the United States.

Signs and symptoms

Dengue fever is manifested by a sudden onset, five to eight days after infection, of high fever, chills, severe headache, muscle and joint pains (myalgias and arthralgias), eye pain, red eyes, enlarged lymph nodes, rash, and extreme weakness. After about two to three days, the symptoms subside, with the fever rapidly dropping, although the patient sweats profusely. Then, after a brief time of from a few hours to two days, symptoms reappear, with an increase in fever (although not as high) and a rash of small bumps appearing on the arms and legs and spreading to the chest, abdomen, and back. There is swelling of the palms of the hand and soles of the feet, which can turn bright red (Carson-DeWitt 2004).

The classic dengue symptoms are known as the '"dengue triad": fever, rash, and headache (Carson-DeWitt 2004). There may also be gastritis with some combination of associated abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea. Other symptoms that may occur are bleeding from nose, mouth or gums, severe dizziness, and loss of appetite.

Some cases develop much milder symptoms, which can be misdiagnosed as influenza or other viral infection when no rash is present. Thus travelers from tropical areas may pass on dengue in their home countries inadvertently, having not been properly diagnosed at the height of their illness. Patients with dengue can pass on the infection only through mosquitoes or blood products and only while they are still febrile (have a fever).

The classic dengue fever lasts about six to seven days, with a smaller peak of fever at the trailing end of the disease (the so-called "biphasic pattern"). Clinically, the platelet count will drop until the patient's temperature is normal. The patient may be fatigued for several weeks.

Cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), when the patient is reinfected with another strain, also show high fever and headache as among the first symptoms, but the other initial symptoms of dengue fever are absent. The patient develops a cough and then the appearance on the skin of small purplish spots (petechiae), which are caused by blood leaking out of the blood vessels. Abdominal pain may be severe and large bruised areas may appear where the blood is escaping from the blood vessels. The patient may vomit something that looks like coffee grounds, which is a sign of bleeding into the stomach (Carson-DeWitt 2004).

A small proportion of DHF cases lead to dengue shock syndrome (DSS) which has a high mortality rate. Shock can damage the body's organs, and especially the heart and kidneys due to low blood flow (Carson-DeWitt 2004).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dengue is usually made clinically. The classic picture is high fever with no localizing source of infection, a petechial rash with thrombocytopenia, and relative leukopenia. In addition, the virus is one of the few types of arboviruses that can be isolated from the blood serum, a result of the phase in which the virus travels in the blood stream is relatively long (Carson-DeWitt 2004). Thus, serology (study of blood serum) using antibodies can be employed to test for the presence of these viruses. In addition, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is available to confirm the diagnosis of dengue if clinically indicated.

The WHO definition of dengue hemorrhagic fever has been in use since 1975; all four criteria must be fulfilled (WHO 1997):

- Fever, bladder problem, constant headaches, severe dizziness, and loss of appetite.

- Hemorrhagic tendency (positive tourniquet test, spontaneous bruising, bleeding from mucosa, gingiva, injection sites, etc.; vomiting blood, or bloody diarrhea).

- Thrombocytopenia (<100,000 platelets per mm³ or estimated as less than three platelets per high power field).

- Evidence of plasma leakage (hematocrit more than 20 percent higher than expected, or drop in haematocrit of 20 percent or more from baseline following IV fluid, pleural effusion, ascites, hypoproteinemia).

Dengue shock syndrome is defined as dengue hemorrhagic fever plus weak rapid pulse, narrow pulse pressure (less than 20 mm Hg), and cold, clammy skin and restlessness.

Treatment and prognosis

There presently is not any available treatment to shorten the course of dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, or dengue shock syndrome (Carson-DeWitt 2004). The mainstay of treatment is supportive therapy. Increased oral fluid intake is recommended to prevent dehydration. Supplementation with intravenous fluids may be necessary to prevent dehydration and significant concentration of the blood if the patient is unable to maintain oral intake. A platelet transfusion is indicated in rare cases if the platelet level drops significantly (below 20,000) or if there is significant bleeding.

The presence of melena may indicate internal gastrointestinal bleeding requiring platelet and/or red blood cell transfusion.

Medications may be given to lower the fever or address the headache and muscle pain. However, aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided as these drugs may worsen the bleeding tendency associated with some of these infections. Patients may receive paracetamol preparations to deal with these symptoms if dengue is suspected (CDC 2007).

Emerging evidence suggests that mycophenolic acid and ribavirin inhibit dengue replication. Initial experiments showed a fivefold increase in defective viral RNA production by cells treated with each drug (Takhampunya et al. 2006). While these offer a possible avenue for future treatment, in vivo studies have not yet been done.

Uncomplicated dengue fever has an excellent prognosis, with almost 100 percent of patients recovering fully. However, DHF has a fatality rate of from six to thirty percent of all patients, with the death rate highest among those under one year old. In the cases of excellent health care, the death rate among DHF and DSS patients lowers to about one percent (Carson-DeWitt 2004).

Prevention

There is no vaccine for dengue, and thus prevention of dengue fever is centered on prevention of infection, either via decreasing the mosquito population or means of personal protection via such measures as insect repellents or mosquito nets.

Mosquito control

Primary prevention of dengue mainly resides in mosquito control. There are two primary methods: larval control and adult mosquito control. In urban areas, Aedes mosquitos breed in standing water in artificial containers such as plastic cups, used tires, broken bottles, flower pots, and so forth. Continued and sustained artificial container reduction or periodic draining of artificial containers is the most effective way of reducing the larva and thereby the aedes mosquito load in the community. Larvicide treatment is another effective way of control the vector larvae but the larvicide chosen should be long lasting and preferably have World Health Organization clearance for use in drinking water. There are some very effective insect growth regulators (IGR's) available that are both safe and long lasting (e.g. pyriproxyfen). For reducing the adult mosquito load, fogging with insecticide is somewhat effective.

In 1998, scientists from the Queensland Institute of Research in Australia and Vietnam's Ministry of Health introduced a scheme that encouraged children to place a water bug, the crustacean Mesocyclops, in water tanks and discarded containers where the Aedes aegypti mosquito was known to thrive. This method is viewed as being more cost-effective and more environmentally friendly than pesticides, though not as effective, and requires the ongoing participation of the community (BBC 2005).

Prevention of mosquito bites is another way of preventing disease. Personal prevention consists of the use of mosquito nets, repellents containing NNDB or DEET, covering exposed skin, use of DEET-impregnated bednets, and avoiding endemic areas.

Vaccine development

There is no commercially available vaccine for the dengue flavivirus. However, one of the many ongoing vaccine development programs is the Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative, which was set up in 2003 with the aim of accelerating the development and introduction of dengue vaccine(s) that are affordable and accessible to poor children in endemic countries (PDVI 2008). There are some vaccine candidates entering phase I or II testing (Edelman 2007).

Potential antiviral approaches

In cell culture experiments (Kinney et al. 2005) and in mice (Burrer et al. 2007; Stein et al. 2008), Morpholino antisense oligos have shown specific activity against dengue virus. (Morpholino is a molecule used to modify gene expression.) Also, in 2006, a group of Argentine scientists discovered the molecular replication mechanism of the virus, which could be attacked by disruption of the polymerase's work (Filomatori et al. 2006).

History and epidemiology

Outbreaks resembling dengue fever have been reported throughout history (Gubler 1998). The disease was identified and named in 1779. The first definitive case report dates from 1789 and is attributed to Benjamin Rush, who coined the term "breakbone fever" (because of the symptoms of myalgia and arthralgia). The viral etiology and the transmission by mosquitoes were deciphered only in the twentieth century. Population movements during World War II spread the disease globally.

The first epidemics occurred almost simultaneously in Asia, Africa, and North America in the 1780s. A global pandemic began in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and by 1975 DHF had become a leading cause of death among many children in many countries in that region.

Epidemic dengue has become more common since the 1980s. By the late 1990s, dengue was the most important mosquito-borne disease affecting humans after malaria, there being around 40 million cases of dengue fever and several hundred thousand cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever each year. There was a serious outbreak in Rio de Janeiro in February 2002 affecting around one million people and killing sixteen. On March 20, 2008, the secretary of health of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Sérgio Côrtes, announced that 23,555 cases of dengue, including 30 deaths, had been recorded in the state in less than three months.

Significant outbreaks of dengue fever tend to occur every five or six months. The cyclicity in numbers of dengue cases is thought to be the result of seasonal cycles interacting with a short-lived cross-immunity for all four strains, in people who have had dengue (Wearing and Rohani 2006). When the cross-immunity wears off, the population is then more susceptible to transmission whenever the next seasonal peak occurs. Thus in the longer term of several years, there tend to remain large numbers of susceptible people in the population despite previous outbreaks because there are four different strains of the dengue virus and because of new susceptible individuals entering the target population, either through childbirth or immigration.

There is significant evidence, originally suggested by S.B. Halstead in the 1970s, that dengue hemorrhagic fever is more likely to occur in patients who have secondary infections by serotypes different from the primary infection. One model to explain this process is known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), which allows for increased uptake and virion replication during a secondary infection with a different strain. Through an immunological phenomenon, known as original antigenic sin, the immune system is not able to adequately respond to the stronger infection, and the secondary infection becomes far more serious (Rothman 2004). This process is also known as superinfection (Nowak and May 1994; Levin and Pimentel 1981).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- BBC. 2005. Water bug aids dengue fever fight BBC News February 11, 2005. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ———. 2007a. Dengue sparks Paraguay emergency BBC News March 2, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ———. 2007b. Paraguay dengue official sacked BBC News March 6, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Burrer, R., B. W. Neuman, J. P. Ting, et al. 2007. Antiviral effects of antisense morpholino oligomers in murine coronavirus infection models. J. Virol. 81(11): 5637–48. PMID 17344287. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Carson-DeWitt, R. 2004. Dengue fever. Pages 1027-1029 in J. L. Longe, The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, 2nd edition, volume 2. Detroit, MI: Gale Group/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0787654914 (volume); ISBN 0787654892 (set).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2008. Chapter 4, Prevention of specific infectious diseases: Dengue fever CDC Traveler's Health: Yellow Book. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ———. 2007. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever: Information for health care practitioners Center for Disease Control. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Downs, W. H., et al. 1965. Virus diseases in the West Indies. Special edition of the Caribbean Medical Journal 26(1-4).

- Earle, K. V. 1965. Notes on the dengue epidemic at Point Fortin. Caribbean Medical Journal 26(1-4): 157-164.

- Edelman, R. 2007. Dengue vaccines approach the finish line Clin. Infect. Dis. 45(Suppl 1): S56–60. PMID 17582571.

- Filomatori, C. V., M. F. Lodeiro, D. E. Alvarez, M. M. Samsa, L. Pietrasanta, and A. V. Gamarnik. 2006. A 5' RNA element promotes dengue virus RNA synthesis on a circular genome Genes Dev. 20(16): 2238–49. PMID 16882970. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Goldman, L., and D. A. Ausiello. 2007. Cecil Textbook of Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 9781416044789.

- Gubler, D. J. 1998. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11(3): 480–96. PMID 9665979.

- Hill, A. E. 1965. Isolation of dengue virus from a human being in Trinidad. In special editon on Virus diseases in the West Indies in Caribbean Medical Journal 26(1-4): 83-84.

- ———. 1965. Dengue and Related Fevers in Trinidad and Tobago. In special edition on Virus diseases in the West Indies in Caribbean Medical Journal 26(1-4): 91-96.

- Kasper, D. L., and T. R. Harrison. 2005. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 0071391401.

- Kinney, R. M., C. Y. Huang, B. C. Rose, et al. 2005. Inhibition of dengue virus serotypes 1 to 4 in vero cell cultures with morpholino oligomers J. Virol. 79(8): 5116–28. PMID 15795296.

- Kouri, G. P., M. G. Guzmán, J. R. Bravo, and C. Triana. 1989. Dengue haemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS): Lessons from the Cuban epidemic, 1981 Bull World Health Organ. 67(4): 375-80. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative (PDVI). 2008. Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative website International Vaccine Institute. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Pham, T. B., T. H. Nguyen, T. Q. Vu, T. L. Nguyen, and D. Malvy. 2007. Predictive factors of dengue shock syndrome at the children Hospital No. 1, Ho-chi-Minh City, Vietnam Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 100(1): 43-47.Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Rothman, A. L. 2004. Dengue: Defining protective versus pathologic immunity J. Clin. Invest. 113(7): 946–51. PMID 15057297. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Stein, D. A., C. Y. Huang, S. Silengo, et al. 2008. Treatment of AG129 mice with antisense morpholino oligomers increases survival time following challenge with dengue 2 virus J Antimicrob Chemother. 62(3): 555-65. PMID 18567576.

- Takhampunya, R., S. Ubol, H. S. Houng, C. E. Cameron, and R. Padmanabhan. 2006. Inhibition of dengue virus replication by mycophenolic acid and ribavirin J. Gen. Virol. 87(Pt 7): 1947–52. PMID 16760396. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Theiler, M., and W. G. Downs. 1973. The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates: An Account of The Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program 1951-1970. Yale University Press.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 1997. Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever: Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control, 2nd edition Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9241545003.

- ———. 2008. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever World Health Organization. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Warrell, D. A. 2003. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192629220.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.