Dizi

The dizi (Chinese: 笛子]]; pinyin: dízi), is a Chinese transverse flute, usually made of bamboo. It is also sometimes known as the di (笛) or hengdi (橫笛), and has varieties including the qudi (曲笛) and bangdi (梆笛). The dizi is simple to make and easy to carry. It is widely used in many genres of Chinese folk music, as well as Chinese opera, and the modern Chinese orchestra.

The dizi has a very simple structure, with one blowhole, six finger holes, and an additional hole, called a mo kong (膜孔) between the embouchure and the sixth finger-hole. A special membrane called dimo (笛膜]], "di membrane"), made from an almost tissue-like shaving from the inner tube of a bamboo or reed, is made taut and glued over this hole, traditionally with a substance called ejiao. The dimo covered mokong has a distinctive resonating effect on the sound produced by the dizi, making it brighter and louder, and adding harmonics to give the final tone a buzzing, nasal quality. Dizi have a relatively large range, covering about two-and-a-quarter octaves. Most Dizi players only use three or four of their fingers to alter pitches, relying on a set of seven or twelve flutes in varying lengths for all the keys.

Description

The dizi is an important Chinese musical instrument, and is widely used in many genres of Chinese folk music, as well as Chinese opera, and the modern Chinese orchestra. Traditionally, the dizi has also been popular among the Chinese common people, and in contrast to the xiao, a vertical bamboo flute which has historically been favored by scholars and the upper classes, it is simple to make and easy to carry.

Most dizi are made of bamboo, and it is sometimes called simply the "Chinese bamboo flute." Although bamboo is the common material for the dizi, it is also possible to find dizi made from other kinds of wood, or even from stone. Jade dizi (or yudi, 玉笛) are popular among both collectors interested in the magical beauty of jade dizi, and professional players who seek an instrument with an elegance that matches the quality of their renditions. However, jade is not the best material for dizi since it is not as resonant as bamboo. The dizi has a very simple structure: one blowhole, one membrane hole, six finger holes, and two pairs of holes in the end to correct the pitch and hang decorative tassels. Some have poems inscribed near the head joint, or jade ornaments at both ends. Several different lacquer finishes are used, and often ornate bands decorate the length of the dizi.

The dizi is not the only bamboo flute of China, although it is certainly distinctive. Other Chinese bamboo wind instruments include the vertical end-blown xiao, the guanzi (double reed), the koudi, and the bawu (free reed).

Membrane

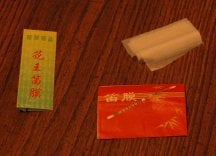

While most simple flutes have only a blowing hole (known as chui kong in Chinese) and finger-holes, the dizi has an additional hole, called a mo kong (膜孔, mo-cong), between the embouchure and the sixth finger-hole. The mo kong was invented in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 C.E.) by Liu Xi, who named the flute the "Seven Star Tube." A special membrane called dimo (笛膜]], "di membrane"), made from an almost tissue-like shaving from the inner tube of a bamboo or reed, is made taut and glued over this hole, traditionally with a substance called ejiao. Garlic juice or glue sticks may also be used to adhere the dimo. This application process, in which fine wrinkles are created in the centre of the dimo to create a penetrating buzzy timbre, is an art form in itself.

The dimo covered mokong has a distinctive resonating effect on the sound produced by the dizi, making it brighter and louder, and adding harmonics to give the final tone a buzzing, nasal quality. Dizi have a relatively large range, covering about two-and-a-quarter octaves. The membrane can be adjusted to create the right tone for a specific musical mood.

Techniques

Dizi are often played using various "advanced" techniques, such as circular breathing, slides, popped notes, harmonics, "flying finger" trills, multiphonics, fluttertonguing, and double-tonguing. Most professional players have a set of seven dizi, each in a different key (and size). Additionally, master players and those seeking distinctive sounds such as birdsong may use extremely small or very large dizi. Half steps and micro tones are played by partially covering the appropriate finger hole, but most Dizi players only use three or four of their fingers to alter pitches, relying on a set of seven or twelve flutes in varying lengths for all the keys. The Dizi's range is two octaves plus two or thee notes, depending on its size.

Origins

There are many theories concerning the origin of the dizi. Legend recounts that the Yellow Emperor ordered his government official to make the bamboo musical instrument, while others believe that dizi was imported into China during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.). Official documents record that the dizi was brought back from somewhere west of China by Emperor Wudi's messenger, Zhang Qian, in 119 B.C.E.. However, the discovery of older flutes in several ancient tombs indicates that the Chinese played bone and bamboo flutes long before that. A flute was found in a tomb of Eastern Han (206 B.C.E.-9 C.E.) with an extra hole, perhaps for pasting a membrane. A long and a short bamboo flute were discovered in a tomb dated 168 B.C.E. Bone flutes 7,000 years old were found in Hemudu, Zhejiang province. Recently, archaeologists have discovered evidence suggesting that the simple transverse flutes (though without the distinctive mokong of the dizi) have been present in China for over 9,000 years. Fragments of bone flutes from this period, made from the wing bones of the red-crowned crane and carved with five to seven holes, were found at the Jiahu site in the Yellow River Valley.[1] Some of these are still playable today, and are remarkably similar to modern versions in terms of hole placement. These flutes share common features with other simple flutes from cultures all around the world, including the ney, an end-blown cane flute which was depicted in Egyptian paintings and stone carvings. Recent archeological discoveries in Africa suggest that the history of such flutes may be very ancient.

The first written record of the membrane (dimo) dates from the twelfth century. On traditional dizi, the finger-holes are spaced approximately equidistantly, which produces a temperament of mixed whole-tone and three-quarter-tone intervals. During the middle of the twentieth century, makers of dizi began to change the finger hole placements to allow for playing in equal temperament, as demanded by new musical developments and compositions, although traditional dizi continue to be used for purposes such as accompaniment of kunqu, the oldest extant form of Chinese opera. A fully chromatic version of the dizi, called xindi, usually lacks the dizi’s buzzing membrane (dimo).

Styles

Contemporary dizi styles based on the professional conservatory repertory are divided into Northern and Southern, each style having different preferences in dizi and playing techniques. In Northern China, for example, the bangdi is used to accompany Bangzi opera, with a sound that is bright and vigorous. In Southern China, the qudi accompanies Kunqu opera and is used in music such as Jiangnan Sizhu, which has a more mellow, lyrical tone.

Performers

Major dizi performers of the twentieth century who have contributed to dizi playing in the new conservatory professional concert repertory, often based on or adapted from regional folk styles, include Feng Zicun, Liu Guanyue, Lu Chunling and Zhao Songting.

Feng Zicun (冯子存,1904-1987) was born in Yangyuan, Hebei province. Of humble origins, Feng had established himself as a folk musician by the time of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, playing the dizi as well as the four-string fiddle sihu in local song and dance groups, folksongs and stilt dances. He also introduced errentai, the local opera of inner Mongolia, to Hebei after spending four years there as a musician in the 1920s.

In 1953, Feng was appointed to the state-supported Central Song and Dance Ensemble in Beijing as dizi soloist, and accepted a teaching post at the China Conservatory of Music (Beijing) in 1964. Feng adapted traditional folk ensemble pieces into dizi solos, such as Xi xiang feng (Happy Reunion), and Wu bangzi (Five Clappers), contributing to the new Chinese conservatory curricula in traditional instrument performance. Feng’s style, virtuosic and lively, is representative of the folk music traditions of northern China.

Liu Guanyue (刘管乐,1918- ) was born in An'guo county, Hebei. Born to a poor peasant family, Liu was a professional folk musician who had earned a meager living playing the guanzi, suona, and dizi in rural ritual ensembles before becoming a soloist in the Tianjin Song-and-Dance Ensemble (Tianjin gewutuan) in 1952. Liu, together with Feng Zicun, is said to be a representative of the Northern dizi style. His pieces, including Yin zhong niao (Birds in the Shade), He ping ge (Doves of Peace) and Gu xiang (Old Home village), have become part of the new conservatory professional concert repertory.

Lu Chunling (陆春龄,1921- ) was born in Shanghai. In pre-1949 Shanghai, Lu worked as a trishaw driver, but was also an amateur musician, performing the Jiangnan sizhu folk ensemble repertory. In 1952, Lu became dizi soloist with the Shanghai Folk Ensemble (Shanghai minzu yuetuan), and also with the Shanghai Opera Company (Shanghai geju yuan) from 1971 to 1976. In 1957 he taught at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, and became Associate Professor in 1978.

Lu has performed in many countries as well as throughout China, and has made many recordings. His dizi playing style has become representative of the Jiangnan dizi tradition in general. He is well known as a longtime member of the famous Jiangnan sizhu music performance quartet consisting of Zhou Hao, Zhou Hui, and Ma Shenglong. His compositions include Jinxi (Today and Yesterday).

Zhao Songting (zh:趙松庭,1924- ) was born in Dongyang county, Zhejiang. Zhao had trained as a teacher in Zhejiang, and had studied law, and Chinese and Western music in Shanghai. In the 1940s he worked as a music teacher in Zhejiang, and became the dizi soloist in the Zhejiang Song and Dance Ensemble (Zhejiang Sheng Gewutuan) in 1956. He also taught at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music and the Zhejiang College of Arts (Zhejiang sheng yishu xuexiao).

Because of his middle class background, Zhao suffered in the political campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s and was not allowed to perform; instead he taught many students who went on to become leading professional dizi players, and to refine dizi design. He has been reinstated in his former positions since 1976. Zhao's compositions include San wu qi (Three-Five-Seven), which is based on a melody from wuju (Zhejiang traditional opera).

See also

- Chinese flutes

- Traditional Chinese musical instruments

- Koudi

- Music of China

Notes

- ↑ The Dizi, Tim Liu.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Li, Ming. Di-zi the history and performance practice of the Chinese bamboo transverse flute. Thesis (Mus. D.), Florida State University, 1995.

- Lee, Yuan-Yuan, and Sin-yan Shen. Chinese musical instruments. Chinese music monograph series. Chicago: Chinese Music Society of North America, 1999. ISBN 1880464039

- Sadie, Stanley, and John Tyrrell. The new Grove dictionary of music and musicians. New York: Grove, 2001. ISBN 1561592390

- Thrasher, Alan R. Chinese musical instruments. Images of Asia. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195907779

- Xiao, Mei, Bell Yung, and Anita Wong. The Musical arts of ancient China 27.9-2001-8.1.2002. Hong Kong: University Museum and Art Gallery, the University of Hong Kong, 2001. ISBN 9628038370

| Traditional Chinese musical instruments | ||

|---|---|---|

| █ Silk (string): Plucked: Guqin • Se • Guzheng • Konghou • Pipa • Sanxian • Ruan • Liuqin • Yueqin • Qinqin • Duxianqin █ Bowed: Huqin • Erhu • Zhonghu • Gaohu • Banhu • Jinghu • Erxian • Tiqin • Yehu • Tuhu • Jiaohu • Sihu • Sanhu • Zhuihu • Zhuiqin • Leiqin • Dihu • (Xiaodihu • Zhongdihu • Dadihu) • Gehu • Diyingehu • Laruan • Matouqin • Yazheng █ Struck: Yangqin • Zhu | ||

| █ Bamboo (woodwind): Flutes: Dizi • Xiao • Paixiao • Koudi █ Oboes: Guan • Suona █ Free-reed pipes: Bawu • Mangtong | ||

| █ Gourd (woodwind): Sheng • Yu • Lusheng • Hulusi • Hulusheng | ||

| █ Percussion: Wood: Muyu • Guban █ Stone: Bianqing █ Metal: Bianzhong • Fangxiang • Luo • Yunluo █ Clay: Xun █ Hide: Daigu • Bangu • Paigu • Tanggu | ||

| █ Others: Gudi • Lusheng • Kouxian | ||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.