Emperor Hirohito

Emperor Hirohito or Emperor ShÅwa (æå天ç, ShÅwa TennÅ) (April 29, 1901 - January 7, 1989) was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989. His reign was the longest of any historical Japanese emperor, and he oversaw many significant changes to Japanese society.

In 1937, Japan engaged in war with China for a second time, and in 1941, it entered the Second World War with the United States and its Allies. In early August 1945, Japan was the site of the only two atomic bomb attacks in history to date, and surrendered to the allied powers in 1945. From 1945â1952, Japan underwent its only foreign occupation in history. The 1960s and 1970s brought about an economic miracle, during which Japan became the second largest economy in the world.

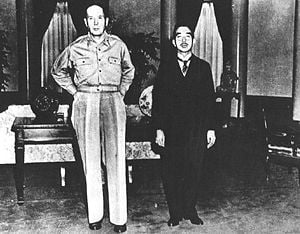

Emperor Hirohito was a capable and intelligent leader. Though shy and reclusive, he was intelligent and serious, and kept himself informed of political and military activities. There is much discussion about how much responsibility for Japanâs involvement in China and World War II can be attributed to Emperor Hirohito. After Japan surrendered at the end of World War II, he presented himself to General Douglas MacArthur and offered to do anything necessary to take responsibility for the war. Renouncing his quasi-divine status as a condition of surrender, he then went about transforming the role of the Imperial Family in Japan. He developed a public personality and began representing Japan as a ceremonial head of state in the manner of European constitutional monarchs, breaking many ancient precedents.

Name

Emperor Hirohitoâs original name was Michinomiya Hirohito; like all his predecessors, he has been known since his death by a posthumous name, that, according to a tradition dating back to 1912, is the name of the Japanese era coinciding with his reign. Having ruled during the ShÅwa era (Enlightened Peace), he is now known as Emperor ShÅwa. Although he is widely referred to as Hirohito or Emperor Hirohito outside of Japan; Japanese emperors are only referred to in Japan by their posthumous names. In Japan, the use of his personal name instead can be considered overly familiar, almost derogatory.

Early life

Michinomiya Hirohito (personal name Hirohito, è£ä») was born in the Aoyama Palace in Tokyo, on April 29, 1901, the first son of Crown Prince Yoshihito (the future Emperor TaishÅ) and Crown Princess Sadako (the future Empress Teimei). His childhood title was Prince Michi (迪宮, Michi no miya). He became heir apparent upon the death of his grandfather, Emperor Meiji, on July 30, 1912. His formal investiture as crown prince took place on November 2, 1916.

From 1908 to 1914, he attended the boy's department of Gakushuin Peer's School, whose principal was Maresuke Nogi, the victorious infantry general of the Russo-Japanese war and an embodiment of ancient samurai virtues. (In 1912, on the day of Emperor Meiji's funeral, Nogi and his wife committed the ceremonial suicide of junshi, "following one's lord in death.") Nogi and two Confucian teachers tutored him about imperial duty. Hirohito then attended a special institute for the crown prince (TÅgÅ«-gogakumonsho) from 1914 to 1921.

Early in life, he became interested in marine biology, and later wrote several books on the subject. In 1921, Prince Regent Hirohito became the first Japanese crown prince to travel abroad when he took a six month tour of Europe, including the United Kingdom, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. On November 29, 1921, he became regent of Japan, in place of his father, who was suffering from mental illness.

Family

On January 26, 1924, he married his distant cousin, Princess Nagako Kuni (the future Empress KÅjun), the eldest daughter of Prince Kuni Kuniyoshi, and they had two sons and five daughters:

- Princess Shigeko, childhood appellation Teru no miya (ç §å®®æå teru no miya shigeko), December 9, 1925âJuly 23, 1961; m. October 10, 1943, to Prince Higashikuni Morihiro (May 6, 1916âFebruary 1, 1969), the eldest son of Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko and his wife, Princess Toshiko, the eighth daughter of Emperor Meiji; lost status as imperial family members, October 14, 1947

- Princess Sachiko, childhood appellation Hisa no miya (ä¹ å®®ç¥å hisa no miya sachiko), September 10, 1927âMarch 8, 1928

- Princess Kazuko, childhood appellation Taka no miya (åå®®åå taka no miya kazuko), September 30, 1929âMay 28, 1989; married May 5, 1950 to Takatsukasa Toshimichi (August 26, 1923âJanuary 27, 1966), eldest son of Takatsukasa Nobusuke [peer]; and had a son, Naotake

- Princess Ikeda, Atsuko, childhood appellation Yori no miya (é å®®åå yori no miya atsuko), March 7, 1931; married October 10, 1952 to Ikeda Takamasa (b. October 21, 1927), eldest son of former Marquis Nobumasa Ikeda

- Crown Prince Akihito, childhood appellation Tsugu no miya (ç¶å®®æä» tsugu no miya akihito) became the present Emperor of Japan, b. December 23, 1933; married April 10, 1959, to Michiko (the present ShÅda Empress of Japan, b. October 20, 1934), elder daughter of ShÅda Hidesaburo, former president and chairman of Nisshin Flour Milling Company

- Prince Masahito, childhood appellation Yoshi no miya (義宮æ£ä» yoshi no miya masahito), b. November 28, 1935, titled Prince Hitachi (常é¸å®® hitachi no miya) since October 1964; m. October 30, 1964, to Tsugaru Hanako (b. July 19, 1940), fourth daughter of former Count Tsugaru Yoshitaka

- Princess Shimazu, Takako, childhood appellation Suga no miya (æ¸ å®®è²´å suga no miya takako), b. March 3, 1939 ; m. March 3, 1960, Shimazu Hisanaga, son of former Count Shimazu Hisanori and has a son, Yoshihisa

The daughters who lived to adulthood left the imperial family as a result of the American reforms of the Japanese imperial household in October 1947 (in the case of Princess Higashikuni), or under the terms of the Imperial Household Law at the moment of their subsequent marriages (in the cases of Princesses Kazuko, Atsuko, and Takako).

Accession

On December 25, 1926, following the death of his father, Hirohito became the 124th emperor of Japan. His reign was designated Showa, or âEnlightened Peace.â According to the Japanese constitution, he was invested with supreme authority, but in practice he merely ratified the policies that were formulated by his ministers and advisers.

Early reign

The first part of Emperor ShÅwa's reign as sovereign (between 1926 and 1945) saw an increase in the power of the military within the government, through both legal and extralegal means. The Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy had held veto power over the formation of cabinets since 1900, and between 1921 and 1944, there were no fewer than sixty-four incidents of right-wing political violence.

The assassination of moderate Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, in 1932, marked the end of any real civilian control of the military. This was followed by an attempted military coup in February 1936, the February 26 Incident, mounted by junior Army officers of the KÅdÅha faction who had the sympathy of many high-ranking officers including Prince Chichibu (Yasuhito), one of the emperor's brothers. The coup occurred when the militarist faction lost ground in Diet elections, and resulted in the murder of a number of high government and Army officials. Emperor Hirohito angrily assumed a major role in confronting the rebels. When Chief Aide-de-camp Shigeru HonjÅ informed him of the revolt, the emperor immediately ordered that it be put down, and referred to the officers as rebels (bÅto). Shortly thereafter, he ordered Army minister Yoshiyuki Kawashima to suppress the rebels within one hour, and he asked for reports on the situation to be made every thirty minutes. The next day, when told by HonjÅ that little progress was being made by the high command in quashing the rebels, the emperor told him "I myself will lead the Konoe Division and subdue them." This was not necessary; on February 29, the rebellion was suppressed.[1]

From the 1930s, the military clique held almost all political power in Japan, and pursued policies that eventually led Japan to fight the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937) and World War II (1945).

World War II

Many historians have asserted that Emperor Hirohito personally had grave misgivings about war with the United States and opposed Japan's alliance with Germany and Italy, but was powerless to resist the military figures who dominated the armed forces and the government. Other historians claim that Emperor Hirohito might have been involved in the planning of Japan's expansionist policies from 1931 to World War II, in closed meetings with his cabinet and military advisers. Historical perception of the emperor may have been distorted by the secrecy in which he lived before World War II, and the efforts of the Allies to redefine the role of the Emperor after the war.

According to the traditional view, Emperor ShÅwa was deeply concerned by the decision to place "war preparations first and diplomatic negotiations second," and he announced his intention to break with tradition. At the Imperial Conference on September 5, 1941, he directly questioned the chiefs of the Army and Navy general staffs, a quite unprecedented action. Nevertheless, all speakers at the Imperial Conference were united in favor of war rather than diplomacy. Baron Yoshimichi Hara, President of the Imperial Council and the emperor's representative, then questioned them closely, producing replies to the effect that war would only be considered as a last resort from some, and silence from others. At this point, Emperor Hirohito astonished all present by addressing the conference personally, and in breaking the tradition of Imperial silence left his advisers, "struck with awe." (Prime Minister Konoe's description of the event.) Emperor ShÅwa stressed the need for peaceful resolution of international problems, expressed regret at his ministers' failure to respond to Baron Hara's probings, and recited a poem written by his grandfather, Emperor Meiji which, he said, he had read "over and over again: Methinks all the people of the world are brethren, then. Why are the waves and the wind so unsettled nowadays?"

Recovering from their shock, the ministers hastened to express their profound wish to explore all possible peaceful avenues.

Near the end of the war, in 1945, Japan was close to defeat and the country's leaders were divided between those wishing to surrender, and those insisting on a desperate defense of the home islands against an anticipated Allied invasion. Emperor Hirohito settled the dispute in favor of those who wanted peace. On August 15, 1945, he broke the precedent of imperial silence by making a national radio broadcast to announce Japan's acceptance of the Allies' terms of surrender. In a second historic broadcast on January 1, 1946, Hirohito publicly repudiated the traditional quasi-divine status of Japan's emperors.

Allied occupation

Emperor ShÅwa chose his uncle, Prince Higashikuni, as prime minister to assist the occupation. There were attempts by various leaders, among them United States President Harry S. Truman, to have the Emperor put on trial for alleged war crimes. Members of the imperial family, such as princes Chichibu, Takamatsu, and Higashikuni, pressured the emperor to abdicate so that one of the princes could serve as regent until Crown Prince Akihito came of age.[2] On February 27, 1946, the emperor's youngest brother, Prince Mikasa (Takahito), even stood up in the privy council and indirectly urged the emperor to step down and accept responsibility for Japan's defeat. According to the diary of Ashida, Minister of Welfare, "Everyone seemed to ponder Mikasa's words. Never have I seen His Majesty's face so pale."[3]

United States General Douglas MacArthur, however, insisted that Emperor ShÅwa retain the throne. MacArthur saw him as a symbol of the continuity and cohesion of the Japanese people. Many historians criticize this decision to exonerate the Emperor and the members of the imperial family implicated in the war from criminal prosecution.[4] Before the war crimes trials convened, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP), the International Peace and Security (IPS), and Shôwa officials worked behind the scenes to not only prevent the imperial family being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the Emperor. While the individuals arrested as Class A suspects and incarcerated in Sugamo prison solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility.[5] High officials in court circles and the shôwa government collaborated with allied General Headquarters in compiling lists of prospective war criminals. Thus, "months before the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for the bombing of Pearl Harbor to Hideki TÅjÅ"[6] by allowing "the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the Emperor would be spared from indictment." According to John Dower, "This successful campaign to absolve the Emperor of war responsibility knew no bounds. Hirohito was not merely presented as being innocent of any formal acts that might make him culpable to indictment as a war criminal. He was turned into an almost saintly figure who did not even bear moral responsibility for the war."[7] According to Bix, "MacArthur's truly extraordinary measures to save Hirohito from trial as a war criminal had a lasting and profoundly distorting impact on Japanese understanding of the lost war."[8]

The emperor was not put on trial, but he was forced to explicitly reject (in the Ningen-sengen, 人é宣è¨) the traditional claim that the emperor of Japan was divine, and a descendant of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. According to the Japanese constitution of 1889, the emperor had a divine power over his country, which was derived from the mythology of the Japanese Imperial Family, who were said to be the offspring of the ancestor of Japan, Amaterasu. Before World War II, Tatsukichi Minobe had caused a furor by advocating the theory that sovereignty resides in the states, of which the emperor is just an organ (the tennÅ kikan setsu). He was forced to resign from the House of Peers and his post at the Tokyo Imperial University in 1935, his books were banned and an attempt was made on his life.[9] It was not until 1946 that the emperor's title was altered from "imperial sovereign" to "constitutional monarch." Immediately after Emperor ShÅwa's repudiation of divinity, he asked the occupation authorities for permission to worship the Sun Goddess. Some have seen this as an implicit reaffirmation of the claim to divine status; others have seen it as simply an expression of the emperor's personal religious beliefs, with no political or social implications.

Although the emperor was compelled to reject claims to his own divine status, his public position was deliberately left vague, both because General MacArthur thought the Emperor could be useful in gaining Japanese acceptance of the occupation, and because Shigeru Yoshida wished to thwart attempts to cast him as a European-style monarch. While Emperor ShÅwa was usually seen from abroad as a head of state, there is still a broad dispute about whether he became a common citizen or retained a special status related to his religious offices and participation in Shinto and Buddhist calendar rituals. Many scholars claim that today's tennÅ (usually translated âEmperor of Japanâ in English) is not an emperor.

Post-war reign

Under a new constitution drafted by the United States occupation authorities, Japan became a constitutional monarchy, with sovereignty residing in the people, and the emperorâs powers greatly curtailed. Emperor Hirohito began to make numerous public appearances and permitted unprecedented publication of pictures and stories about his personal and family life, in an effort to make the Japanese people feel closer to the imperial family. In 1959, his oldest son, Crown Prince Akihito, broke a 1,500-year tradition and married a commoner, Shoda Michiko, the daughter of the former president and chairman of Nisshin Flour Milling Company; In 1971, Hirohito toured Europe and broke another tradition by becoming the first reigning Japanese monarch to visit abroad. In 1975, he made a state visit to the United States.

For the rest of his life, Emperor ShÅwa was an active figure in Japanese life, and performed many of the duties commonly associated with a constitutional head of state. The emperor and his family maintained a strong public presence, often holding public walk abouts, and making public appearances at special events and ceremonies. He also played an important role in rebuilding Japan's diplomatic image, traveling abroad to meet with many foreign leaders, including numerous American presidents and Queen Elizabeth II. In 1975, the emperor and the empress were honored guests at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, the first such visit by Japanese royalty.

Emperor Hirohito was deeply interested in and well-informed about marine biology, and the Imperial Palace contained a laboratory from which the emperor published several papers in the field under his personal name "Hirohito." His contributions included the description of several dozen species of jellyfish new to science.

Death and state funeral

On September 22, 1987, the emperor underwent surgery on his pancreas after having digestive problems for several months. This was the very first time a Japanese emperor underwent surgery. The doctors discovered that he had duodenal cancer, but in accordance with Japanese tradition, they did not tell him.[10] He seemed to be recovering well for several months after his surgery. About a year later, however, on September 19, 1988, he collapsed in his palace, and his health worsened over the next several months as he suffered from continuous internal bleeding. On January 7, 1989, at 6:33 a.m., the emperor died. At 7:55 a.m., the grand steward of Japan's Imperial Household Agency, Shoichi Fujimori, officially announced the emperor's death, and revealed details about his cancer for the first time. Emperor Hirohito had been the longest-reigning Japanese emperor. He was succeeded at once by his son, Akihito.

His death marked the end of the ShÅwa era and the immediate beginning of the Heisei era. From January 7 until January 31, the formal appellation of the late emperor was "TaikÅ TennÅ (大è¡å¤©ç)," which means âthe departed emperor.â His definitive posthumous name was determined on January 13, and formally released on January 31, by the prime minister of Japan. Not surprisingly, he was renamed Emperor ShÅwa (ShÅwa TennÅ), after the era during which he ruled.

On February 24, Emperor ShÅwa's state funeral was held, and unlike that of his predecessor, it was formal but not done in a strictly Shinto manner. A large number of world leaders attended, including U.S. President George H.W. Bush, a former naval aviator who had twice been shot down fighting the Japanese in World War II. The general feeling of public opinion throughout the world at this time was that Emperor ShÅwa's regal presence on the throne had contributed substantially to helping Japan regain economic and political stability during the postwar era. He is buried in the Imperial mausoleum in Hachioji, Tokyo, alongside Emperor TaishÅ, his father.

In an odd way his presence and personality became the one persistent unifying factor for his countrymen in a century of sharp and unexpected transformation. The metamorphosis of his imperial image from the plumed militarist on horseback to the democratic monarch waving to crowds with his crushed fedora remains one of history's most puzzling, leaving basic questions about his ability and his legacy still unanswered a decade after his death.[11]

Notes

- â Mikiso Hane, Emperor Hirohito and His Chief Aide-de-camp, The HonjÅ Diary (Hara ShobÅ, 1975).

- â Bix, p. 571-573.

- â Ashida Hitoshi Nikki, Dai Ikkan (Iwanami Shoten, 1986), p. 82.

- â John Dower, Embracing Defeat (1999).

- â Ibid.

- â Ibid.

- â Ibid.

- â Ibid.

- â Stephen S. Large, Emperor Hirohito and Showa Japan: A Political Biography (Routledge, 1992).

- â J-Revolution.com, Emperor Hirohito. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- â Frank Gibney, Sr., "Japan's wartime monarch outlived his role as god-king, but he oversaw the nation's modern transformation," Time 100: August 23-30, 1999 Vol. 154 No. 7/8.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Behr, Edward. Hirohito: Behind the Myth. New York: Villard Books, 1989. ISBN 0394580729

- Bix, Herbert P. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Collins, 2000. ISBN 0-06-019314-X

- Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999. ISBN 0393046869

- HonjÅ, Shigeru and Mikiso Hane. Emperor Hirohito and his Chief Aide-de-Camp: The HonjÅ Diary, 1933-36. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1982. ISBN 0860083195

- Harvey, Robert. American Shogun: General MacArthur, Emperor Hirohito and the Drama of Modern Japan. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2006. ISBN 1585676829

- Hoyt, Edwin P. Hirohito: The Emperor and the Man. Praeger Publishers, 1992. ISBN 0-275-94069-1

- Kawahara, Toshiaki. Hirohito and His Times: A Japanese Perspective. Kodansha International, 1997. ISBN 0-87011-979-6

- Large, Stephen S. Emperor Hirohito and ShÅwa Japan: A Political Biography. London: Routledge, 1992. ISBN 0415032032

- Mosley, Leonard. Hirohito, Emperor of Japan. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1966. ISBN 1-111-75539-6

- Seagrave, Sterling and Peggy Seagrave. The Yamato Dynasty: The Secret History of Japan's Imperial Family. New York: Broadway Books, 1999. ISBN 0767904966

- Wetzler, Peter. Hirohito and War: Imperial Tradition and Military Decision Making in Prewar Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8248-1925-X

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.