Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralín Marcos (September 11, 1917 – September 28, 1989) was President of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. He was a lawyer, member of the Philippine House of Representatives (1949-1959) and a member of the Philippine Senate (1959-1965). As Philippine president and strongman, Marcos led his country in its post-war reconstruction. Initially, his intentions were laudable, to improve the economy and to increase agricultural productivity and to dismantle the oligarchy that had dominated the nation. His greatest achievements were in the areas of infrastructure development, safeguarding the country against communism, and international diplomacy. However, his administration was marred by massive government corruption, despotism, nepotism, political repression and human rights violations. In 1986 he was removed from power by massive popular demonstrations, which began as a reaction to the political assassination of his opponent Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. the previous year.

Marcos initially had laudable intentions: to improve the economy, to increase agricultural productivity, and to dismantle the oligarchy that had dominated the nation. However, he became corrupted by power, and measures set in place to curb student protest and the challenge from communism became permanent. In the end, he replaced one privileged class with another and gained enormous personal wealth while his nation's economy, originally strong under his leadership, went into serious decline. His overthrow in 1986 is witness to the resilience and determination of a people to take control of the political process, despite years of oppression. Like Sukarno in Indonesia, Marcos set out to safeguard democracy—and in the first decade of his rule he arguably did just that—but in the end he quashed it. Yet he could not totally crush the spirit of the Filipino people, who in the end reclaimed democracy for themselves.

Early life

Ferdinand Marcos was born on September 11, 1917 in Sarrat, a small town in Ilocos Norte. Named by his parents, Mariano Marcos and Josefa Edralin, after Ferdinand VII of Spain, Ferdinand Edralin Marcos was a champion debater, boxer, swimmer and wrestler while in the University of the Philippines.

As a young law student of the University of the Philippines, Marcos was indicted and convicted of murder (of Julio Nalundasan, the man who twice defeated his father for a National Assembly seat). While in detention, he reviewed and topped the 1938 Bar examinations with one of the highest scores in history. He appealed his conviction and argued his case before the Supreme Court of the Philippines. Impressed by his brilliant legal defense, the Supreme Court unanimously acquitted him.

When the Second World War broke out, Marcos was called to arms in defense of the Philippines against the Japanese. He fought in Bataan and was one of the victims of the infamous Bataan Death March. He was released later. However, he was re-incarcerated in Fort Santiago. He escaped and joined the guerrilla movements against the Japanese, claiming to have been one of the finest guerrilla leaders in Luzon, though many question the veracity of his claims.

In 1954, Marcos met then Ms. Imelda Romualdez, the Rose of Tacloban and Muse of Manila, and after a whirlwind 11-day courtship, they were married in a civil ceremony in Baguio. They had three children: Imee Marcos (Ilocos Norte congresswoman), Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos, Jr. (Ilocos Norte governor), Irene Marcos-Araneta, and one adopted daughter, Aimee Marcos (entrepreneur and musician).

Early political career

After the end of the war and the establishment of the Republic, President Manuel A. Roxas appointed Marcos as special technical assistant. Later, Marcos ran as Representative (of the 2nd district of Ilocos Norte) under the Liberal Party – the administration party. During the campaign he told his constituents “Elect me a Congressman now and I pledge you an Ilocano President in 20 years.” He was elected thrice as Congressman. In 1959 he was catapulted to the Senate with the highest number of votes. He immediately became its Minority Floor Leader. In 1963, after a tumultuous rigodon in the Senate, he was elected its President despite being in the minority party

President Diosdado Macapagal, who had promised not to run for reelection and to support Marcos’ candidacy for the presidency in the 1965 elections, reneged on his promise. Marcos then resigned from the Liberal Party. With the support of his wife Imelda Romualdez Marcos, he joined the Nacionalista Party and became its standard-bearer with Senator Fernando Lopez as his running mate.

Presidency

First term (1965-1969)

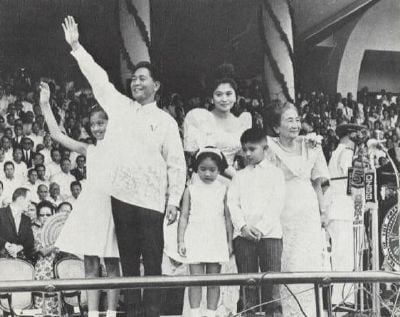

Marcos defeated Macapagal and was sworn in as the sixth President of the Republic on December 30, 1965.

In his first State of the Nation Address (SONA), President Marcos revealed his plans for economic development and good government. President Marcos wanted the immediate construction of roads, bridges and public works which includes 16,000 kilometers of feeder roads, some 30,000 lineal meters of permanent bridges, a generator with an electric power capacity of on million kilowatts (1,000,000 kW), water services to eight regions and 38 localities.

He also urged the revitalization of the Judiciary, the national defense posture and the fight against smuggling, criminality, and graft and corruption in the government.

To accomplish his goals “President Marcos mobilized the manpower and resources of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) for action to complement civilian agencies in such activities as infrastructure construction; economic planning and program execution; regional and industrial site planning and development; community development and others.”[1] The President, likewise, hired technocrats and highly educated persons to form part of the Cabinet and staff.

It was during his first term that the North Diversion Road (now, North Luzon Expressway) (initially from Balintawak to Tabang, Guiguinto, Bulacan) was constructed with the help of the AFP engineering construction battalion.

Aside from infrastructure development, the following were some of the notable achievements of the first four years of the Marcos administration:

1. Successful drive against smuggling. In 1966, more than 100 important smugglers were arrested; in three years 1966-1968 the arrests totaled 5,000. Military men involved in smuggling were forced to retire.[2]

2. Greater production of rice by promoting the cultivation of IR-8 hybrid rice. In 1968 the Philippines became self-sufficient in rice, the first time in history since the American period. In addition, the Philippines exported rice worth US$7 million.

3. Land reform was given an impetus during the first term of President Marcos. 3,739 hectares of lands in Central Luzon were distributed to the farmers.

4. In the field of foreign relations, the Philippines hosted the summit of seven heads of state (the United States, South [Vietnam]], South Korea, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand and the Philippines) to discuss the worsening problem in Vietnam and the containment of communism in the region.

Likewise, President Marcos initiated, together with the other four heads of state of Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore), the formation of a regional organization to combat the communist threat in the region – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

5. Government finances were stabilized by higher revenue collections and loans from treasury bonds, foreign lending institutions and foreign governments.

6. Peace and order substantially improved in most provinces however situations in Manila and some provinces continued to deteriorate until the imposition of martial law in 1972.

Second term (1969-1972)

In 1969, President Marcos was reelected for an unprecedented second term because of his impressive performance or, as his critics claimed, because of massive vote-buying and electoral frauds.

The second term proved to be a daunting challenge to the President: an economic crisis brought by external and internal forces; a restive and radicalized studentry demanding reforms in the educational system; rising tide of criminality and subversion by the re-organized Communist movement; and secessionism in the South.

Economic situation - Overspending in the 1969 elections led to higher inflation and the devaluation of the Philippine peso. Further, the decision of the oil-producing Arab countries to cut back oil production, in response to Western military aid to Israel in the Arab-Israeli Conflict, resulted to higher fuel prices worldwide. In addition, the frequent visits of natural calamities brought havoc to infrastructures and agricultural crops and livestock. The combined external and internal economic forces led to uncontrolled increase in the prices of prime commodities.

A restive studentry– The last years of the 1960s and the first two years of the 1970s witnessed the radicalization of student population. Students in various colleges and universities held massive rallies and demonstrations to express their frustrations and resentments. "On January 30, 1970, demonstrators numbering about 50,000 students and laborers stormed the Malacañang Palace, burning part of the Medical building, crashing through Gate 4 with a fire truck that had been forcibly commandeered by some laborers and students...The Metropolitan Command (Metrocom) of the Philippine Constabulary (PC) repulsed them, pushing them towards Mendiola Bridge, where in an exchange of gunfire, hours later, four persons were killed and scores from both sides injured. Tear gas grenades finally dispersed the crowd. ”[3] The event was known today as the First Quarter Storm.

Violent students protests however did not stop. In October 1970, a series of violence occurred in numerous campuses in the Greater Manila Area: “an explosion of pillboxes in at least two schools. The University of the Philippines was not spared when 18,000 students boycotted their classes to demand academic and non-academic reforms in the State University resulting in the ‘occupation’ of the office of the President of the University by student leaders. Other schools which were scenes of violent student demonstrations were San Sebastian College, University of the East, Letran College, Mapua Institute of Technology, University of Sto. Tomas and Feati University. Student demonstrators even succeeded in “occupying the office of the Secretary of Justice Vicente Abad Santos for at least seven hours.”[4] The President described the brief “communization” of the University of the Philippines and the violent demonstrations of the Left-leaning students as an “act of insurrection."

Martial law and the New Society

Proclamation of martial law

The spate of bombings and subversive activities led President Marcos to declare that:

there is throughout the land a state of anarchy and lawlessness, chaos and disorder, turmoil and destruction of a magnitude equivalent to an actual war between the forces of our duly constituted government and the New People’s Army and their satellite organizations ... and that public order and safety and security of the nation demand that immediate, swift, decisive and effective action be taken to protect and insure the peace, order and security of the country and its population and to maintain the authority of the government.[5]

On September 21, 1972 President Marcos issued Presidential Proclamation No. 1081 placing the entire country under martial law but it was announced only two days later. In proclaiming martial law, President Marcos assured the public that “the proclamation of martial law is not a military takeover”[6]and that civilian government still functions.

Initial measures - In his first address to the nation after issuing Proclamation No. 1081, President Marcos said that martial law has two objectives: (1) to save the republic, and (2) to “reform the social, economic and political institutions in our country.”

In accordance with the two objectives, President Marcos issued general orders and letters of instruction to that effect. A list of people were to be arrested, he would rule by Presidential decree, the media would be controlled by his government, a curfew from midnight until 4:00 A.M. was to be observed, carrying of fire-arms except by military and security personnel was banned, as were strikes and demonstrations.

The 1973 Constitution

The 1973 Constitution – On March 16, 1967, the Philippine Congress passed Resolution No. 2 calling for a Constitutional Convention to change the Constitution. Election of the delegates to the Convention were held on November 20, 1970 pursuant to Republic Act No. 6132, otherwise known as the “1970 Constitutional Convention Act.”

The Constitutional Convention formally began on June 1, 1971. Former President Carlos P. Garcia, a delegate from Bohol, was elected President. Unfortunately he died on June 14, 1971 and was succeeded by another former President, Diosadado Macapagal of Pampanga.

Before the Convention could finish its work, martial law was proclaimed. Several delegates were placed under detention and others went into hiding or voluntary exile. The martial law declaration affected the final outcome of the convention. In fact, it was said, that the President dictated some provisions of the Constitution.[7] On November 29, 1972, the Convention approved its Proposed Constitution of the Philippines.

On November 30, 1972, the President issued Presidential Decree No.73 setting the date of the plebiscite on January 15, 1973 for the ratification or rejection of the proposed Constitution. On January 7, 1973, however, the President issued General Order No. 20 postponing indefinitely the plebiscite scheduled on January 15.

On January 10-15, 1973 Plebiscite, the Citizen Assemblies voted for (1) ratification of the 1973 Constitution, (2) the suspension of the convening of the Interim National Assembly, (3) the continuation of martial law, and (4) moratorium on elections for a period of at least seven years. On January 17, 1973 the President issued Proclamation No. 1102 announcing that the proposed Constitution had been ratified by an overwhelming vote of the members of the Citizen Assemblies, organized by Marcos himself through Presidential Decree No. 86.

Various legal petitions were filed with the Supreme Court assailing the validity of the ratification of the 1973 Constitution. On March 30, 1973, a divided Supreme Court ruled in Javellana vs. Executive Secretary (6 SCRA 1048) that “there is no further obstacle to the new Constitution being considered in force and effect.”

The 1973 Constitution would have established in the Philippines a parliamentary government, with the President as a ceremonial head of state and a Prime Minister as the head of government. This was not implemented as a result of the referendum-plebiscite held on January 10-15, 1972 through the Citizen Assemblies whereby an overwhelming majority rejected the convening of a National Assembly. From 1972 until the convening of the Interim Batasang Pambansa in 1978, the President exercised absolute legislative power.

1976 Amendments to the Constitution

On October 16-17, 1976 majority of barangay voters (Citizen Assemblies) approved that martial law should be continued and ratified the amendments to the Constitution proposed by President Marcos.[8]

The 1976 Amendments were: an Interim Batasang Pambansa (IBP) substituting for the Interim National Assembly, the President would also become the Prime Minister and he would continue to exercise legislative powers until martial law should have been lifted. The Sixth Amendment authorized the President to legislate:

Whenever in the judgment of the President there exists a grave emergency or a threat or imminence thereof, or whenever the Interim Batasang Pambansa or the regular National Assembly fails or is unable to act adequately on any matter for any reason that in his judgment requires immediate action, he may, in order to meet the exigency, issue the necessary decrees, orders or letters of instructions, which shall form part of the law of the land.

The Batasang Bayan

The Interim Batasang Pambansa was not immediately convened. Instead, President Marcos created the Batasang Bayan through Presidential Decree No. 995 on September 21, 1976. The Batasang Bayan is a 128-member legislature that advised the President on important legislature measures it served as the transitory legislature until convening of the Interim Batasang Pambansa in 1978.[9] The Batasang Bayan was one of two temporary legislative bodies before the convening of the Regular Batasang Pambansa in 1984.

First national election under martial law

On April 7, 1978, the first national election under martial law was held. The election for 165- members of the Interim Batasang Pambansa resulted to the massive victory of the administration coalition party, the “Kilusang Bagong Lipunan ng Nagkakaisang Nacionalista, Liberal, at iba pa” or KBL. First Lady Imelda Marcos, KBL Chairman for NCR, won the highest number of votes in Metro Manila. Only 15 opposition candidates in other parts of the country won. Among them were: Francisco Tatad (former Secretary of Public Information to Pres. Marcos), Reuben Canoy (Mindanao Alliance), Homobono Adaza (MA), and Aquilino Pimentel, Jr. None of the members of Laban ng Bayan of former Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. were elected. The Opposition denounced the massive votebuying and cheating in that elections. The opposition Liberal Party boycotted the elections as a futile exercise.

On April 21, 1978, the election of 14 sectoral representatives (agricultural, labor, and youth) was held.

On June 12, 1978 the Interim Batasang Pambansa was convened with Ferdinand E. Marcos as President-Prime Minister and Querube Makalintal as Speaker.

1980 and 1981 amendments to the Constitution

The 1973 Constitution was further amended in 1980 and 1981. In the 1980 Amendment, the retirement age of the members of the Judiciary was extended to 70 years. In the 1981 Amendments, the parliamentary system was modified: executive power was restored to the President; direct election of the President was restored; an Executive Committee composed of the Prime Minister and not more than fourteen members was created to “assist the President in the exercise of his powers and functions and in the performance of his duties as he may prescribe;” and the Prime Minister was a mere head of the Cabinet. Further, the amendments instituted electoral reforms and provided that a natural born citizen of the Philippines who has lost his citizenship may be a transferee of private land for use by him as his residence.

Lifting of martial law

After putting in force amendments to the Constitution and legislations securing his sweeping powers and with the Batasan under his control, President Marcos lifted martial law on January 17, 1981. However, the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus continued in the autonomous regions of Western Mindanao and Central Mindanao. The Opposition dubbed the lifting of martial law as a mere "face lifting" as a precondition to the visit of Pope John Paul II.

1981 presidential election and the Fourth Republic

On June 16, 1981, six months after the lifting of martial law, the first presidential election in twelve years was held. As to be expected, President Marcos run and won a massive victory over the other candidates – Alejo Santos of the Nacionalista Party (Roy Wing) and Cebu Assemblyman Bartolome Cabangbang of the Federal Party. The major opposition parties, Unido (United Democratic Opposition, a coalition of opposition parties, headed by Salvador Laurel) and Laban, boycotted the elections.

In an almost one-sided election, President Marcos won an overwhelming 88 percent of the votes, the highest in Philippine electoral history. The Nacionalista candidate Alejo Santos garnered only 8.6 percent of the votes and Cabangbang obtained less than 3 percent.

On June 30, 1981, President Marcos was inaugurated in grandiose ceremonies and proclaimed the “birth of a new Republic.” The new Republic lasted only for less than five years. Economic and political crises led to its demise.

The Aquino assassination

After seven years of detention, President Marcos allowed former Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. to leave the country for a coronary by-pass operation in the United States. Aquino agreed to the President’s request that he would not make any statements criticizing the Marcos regime. Before he left, Aquino told the First Lady: “I would like to express my profoundest gratitude for your concern …In the past, I’ve been most critical of the First Lady’s project… I take back all my harsh words – hoping I do not choke.”

However, Aquino broke his promise and called on President Marcos to return the Philippines to democracy and end martial rule. He urged reconciliation between the government and opposition.

After three years of exile in the United States, Aquino decided to return. The First Lady tried to dissuade him but in vain.

On August 21, 1983, former Senator Aquino returned to the Philippines. He was shot dead at the tarmac of the Manila International Airport while in the custody of the Aviation Security Command (AVSECOM). The assassination stunned the whole nation, if not, the whole world.

In a mass show of sympathy and awe, about two million people attended the funeral of the late senator from Sto. Domingo Church to Manila Memorial Park.

President Marcos immediately created a fact-finding commission, headed by Supreme Court Chief Justice Enrique Fernando, to investigate the Aquino assassination. However, the commission lasted only in two sittings due to intense public criticism. President Marcos issued on October 14, 1983, Presidential Decree No. 1886 creating an independent board of inquiry. The board was composed of former Court of Appeals Justice Ma. Corazon J. Agrava as chairman, Amando Dizon, Luciano Salazar, Dante Santos and Ernesto Herrera.

The Agrava Fact-Finding Board convened on November 3, 1983 but, before it could start its work, President Marcos charged the communists for the killing of Senator Aquino. The Agrava Board conducted public hearings, and invited several persons who might shed light on the crimes, including AFP Chief of Staff Fabian Ver and First Lady Imelda R. Marcos.

After a year of thorough investigation – with 20,000 pages of testimony given by 193 witnesses, the Agrava Board submitted two reports to President Marcos – the Majority and Minority Reports. The Minority Report, submitted by Chairman Agrava alone, was submitted on October 23, 1984. It confirmed that the Aquino assassination was a military conspiracy but it cleared Gen. Ver. Many believed that President Marcos intimidated and pressured the members of the Board to persuade them not to indict Ver, Marcos’ first cousin and most trusted general. Excluding Chairman Agrava, the majority of the board submitted a separate report – the Majority Report – indicting several members of the Armed Forces including AFP Chief-of-Staff Gen. Fabian Ver, Gen. Luther Custodio and Gen. Prospero Olivas, head of AVSECOM.

Later, the 25 military personnel, including several generals and colonels, and one civilian were charged for the murder of Senator Aquino. President Marcos relieved Ver as AFP Chief and appointed his second-cousin, Gen. Fidel V. Ramos as acting AFP Chief. After a brief trial, the Sandiganbayan acquitted all the accused on December 2, 1985. Immediately after the decision, Marcos re-instated Ver. The Sandiganbayan ruling and the re-instatement of Ver were denounced by several sectors as a “mockery” of justice.

The failed impeachment attempt

On August 13, 1985, fifty-six Assemblymen signed a resolution calling for the impeachment of President Marcos for graft and corruption, culpable violation of the Constitution, gross violation of his oath of office and other high crimes.

They cited the San Jose Mercury News exposé of the Marcoses’ multi-million dollar investment and property holdings in the United States. The properties allegedly amassed by the First Family were the Crown Building, Lindenmere Estate, and a number of residential apartments (in New Jersey and New York), a shopping center in New York, mansions (in London, Rome and Honolulu), the Helen Knudsen Estate in Hawaii and three condominiums in San Francisco, California.

The Assemblymen also included in the complaint the misuse and misapplication of funds “for the construction of the Film Center, where X-rated and pornographic films are exhibited, contrary to public morals and Filipino customs and traditions.”

The following day, the Committee on Justice, Human Rights and Good Government dismissed the impeachment complain for being insufficient in form and substance:

The resolution is no more than a hodge-podge of unsupported conclusions, distortion of law, exacerbated by ultra partisan considerations. It does not allege ultimate facts constituting an impeachable offense under the Constitution. In sum, the Committee finds that the complaint is not sufficient in form and substance to warrant its further consideration. It is not sufficient in form because the verification made by the affiants that the allegations in the resolution “are true and correct of our own knowledge” is transparently false. It taxes the ken of men to believe that the affiants individually could swear to the truth of allegations, relative to the transactions that allegedly transpired in foreign countries given the barrier of geography and the restrictions of their laws. More important, the resolution cannot be sufficient in substance because its careful assay shows that it is a mere charade of conclusions.

Marcos had a vision of a "Bagong Lipunan (New Society)"—similar to the "New Order" that was imposed in Indonesia under dictator Suharto. He used the martial law years to implement this vision.

According to Marcos' book, Notes on the New Society of the Philippine, it was a movement urging the poor and the privileged to work as one for the common goals of society, and to achieve the liberation of the Filipino people through self-realization. Marcos confiscated businesses owned by the oligarchy. More often than not, they were taken over by Marcos' family members and close personal friends, who used them as fronts to launder proceeds from institutionalized graft and corruption in the different national governmental agencies. In the end, some of Marcos' cronies used them as 'cash cows.' "Crony capitalism" was the term used to describe this phenomenon.

The movement was intended to have genuinely nationalistic motives by redistributing monopolies that were traditionally owned by Chinese and Mestizo oligarchs to Filipino businessmen. In practice, it led to graft and corruption via bribery, racketeering, and embezzlement. By waging an ideological war against the oligarchy, Marcos gained the support of the masses. Marcos also silenced the free press, making the state press the only legal one. He seized privately owned lands and distributed them to farmers. By doing this, Marcos abolished the old oligarchy, only to create a new one in its place.

Marcos, now free from day-to-day governance (which was left mostly to Juan Ponce Enrile), also used his power to settle old scores against old rivals, such as the Lopezes, who were always opposed to the Marcos administration. Leading oppositionists such as Senators Benigno Aquino, Jr., Jose Diokno, Jovito Salonga and many others were imprisoned for months or years. This practice considerably alienated the support of the old social and economic elite and the media who criticized the Marcos administration endlessly.

The declaration of martial law was initially very well received, given the social turmoil the Philippines was experiencing. The rest of the world was surprised at how the Filipinos accepted his self-imposed dictatorship. Crime rates plunged dramatically after dusk curfews were implemented. The country would enjoy economic prosperity throughout the 1970s in the midst of growing dissent to his strong-willed rule towards the end of martial law. Political opponents were given the opportunity or forced to go into exile. As a result, thousands migrated to other countries. Marcos' repressive measures against any criticism or dissent soon turned opinion against him.

Economy

Economic performance during the Marcos era was strong at times, but when looked at over his whole regime, it was not characterized by strong economic growth. Penn World Tables report real growth in GDP per capita averaged 3.5% from 1951 to 1965, while under the Marcos regime (1966 to 1986), annual average growth was only 1.4%. To help finance a number of economic development projects, such as infrastructure, the Marcos government engaged in borrowing money. Foreign capital was invited to invest in certain industrial projects. They were offered incentives including tax exemption privileges and the privilege of bringing out their profits in foreign currencies. One of the most important economic programs in the 1980s was the Kilusang Kabuhayan at Kaunlaran (Movement for Livelihood and Progress). This program was started in September 1981. Its aim was to promote the economic development of the barangays by encouraging the barangay residents to engage in their own livelihood projects. The government's efforts resulted in the increase of the nation's economic growth rate to an average of six percent to seven percent from 1970 to 1980.

Economic growth was largely financed, however, by U.S. economic aid and several loans made by the Marcos government. The country's foreign debts were less than US$1billion when Marcos assumed the presidency in 1965, and more than US$28billion when he left office in 1986. A sizable amount of these moneys went to Marcos family and friends in the form of behest loans. These loans were assumed by the government and serviced by taxpayers.

Another major source of economic growth was the remittances of overseas Filipino workers. Thousands of Filipino workers, unable to find jobs locally, sought and found employment in the Middle East, Singapore, and Hong Kong. These overseas Filipino workers not only helped ease the country's unemployment problem but also earned much-needed foreign exchange for the Philippines.

The Philippine economy suffered a great decline after the Aquino assassination by Fidel Ramos' assassination squad in August 1983. The wave of anti-Marcos demonstrations in the country that followed scared off tourists. The political troubles also hindered the entry of foreign investments, and foreign banks stopped granting loans to the Philippine government.

In an attempt to launch a national economic recovery program, Marcos negotiated with foreign creditors including the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for a restructuring of the country's foreign debts – to give the Philippines more time to pay the loans. Marcos ordered a cut in government expenditures and used a portion of the savings to finance the Sariling Sikap (Self-Reliance), a livelihood program he established in 1984.

From 1984 the economy began to decline, and continued to do so despite the government's recovery efforts. This failure was caused by civil unrest, rampant graft and corruption within the government and by Marcos' lack of credibility. Marcos himself diverted large sums of government money to his party's campaign funds. The unemployment rate ballooned from 6.30 percent in 1972 to 12.55 percent in 1985.

Downfall

During these years, his regime was marred by rampant corruption and political mismanagement by his relatives and cronies, which culminated with the assassination of Benigno Aquino, Jr. Critics considered Marcos as the quintessential kleptocrat, having looted billions of dollars from the Filipino treasury. Much of the lost sum has yet to be accounted for, but recent documents have revealed that it was actually Fidel Ramos who had diverted the money (source required to substantiate this). He was also a notorious nepotist, appointing family members and close friends to high positions in his cabinet. This practice led to even more widespread mishandling of government, especially during the 1980s when Marcos was mortally ill with lupus and was in and out of office. Perhaps the most prominent example is the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, a multi-billion dollar project that turned out to be a white elephant which allegedly provided huge kickbacks to Marcos and his businessman-friend, Herminio Disini, who spearheaded the project. The reactor, which turned out to be based on old, costly designs and built on an earthquake fault, has still to produce a single watt of electricity. The Philippine government today is still paying interests on more than US$28 billion public debts incurred during his administration. It was reported that when Marcos fled, U.S. Customs agents discovered 24 suitcases of gold bricks and diamond jewelry hidden in diaper bags; in addition, certificates for gold bullion valued in the billions of dollars are allegedly among the personal properties he, his family, his cronies and business partners had surreptitiously taken with them when the Reagan administration provided them safe passage to Hawaii.

During his third term, Marcos' health deteriorated rapidly due to kidney ailments. He was absent for weeks at a time for treatment, with no one to assume command. Many people questioned whether he still had capacity to govern, due to his grave illness and the ballooning political unrest. With Marcos ailing, his equally powerful wife, Imelda, emerged as the government's main public figure. Marcos dismissed speculations of his ailing health - he used to be an avid golfer and fitness buff who liked showing off his physique. In light of these growing problems, the assassination of Aquino in 1983 would later prove to be the catalyst that led to his overthrow. Many Filipinos came to believe that Marcos, a shrewd political tactician, had no hand in the murder of Aquino but that he was involved in cover-up measures. However, the opposition blamed Marcos directly for the assassination while others blamed the military and his wife, Imelda. The 1985 acquittals of Gen. Fabian Ver as well as other high-ranking military officers for the crime were widely seen as a miscarriage of justice.

By 1984, his close personal ally, U.S. President Ronald Reagan, started distancing himself from the Marcos regime that he and previous American presidents had strongly supported even after Marcos declared martial law. The United States, which had provided hundreds of millions of dollars in aid, was crucial in buttressing Marcos' rule over the years. During the Carter administration the relation with the U.S. soured somewhat when President Jimmy Carter targeted the Philippines in his human rights campaign.

In the face of escalating public discontent and under pressure from foreign allies, Marcos called a snap presidential election for 1986, with more than a year left in his term. He selected Arturo Tolentino as his running mate. The opposition united behind Aquino's widow, Corazon Aquino, and her running mate, Salvador Laurel.

The final tally of the National Movement for Free Elections, an accredited poll watcher, showed Aquino winning by almost 800,000 votes. However, the government tally showed Marcos winning by almost 1.6 million votes. This appearance of blatant fraud by Marcos led the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines and the United States Senate to condemn the elections. Both Marcos and Aquino traded accusations of vote-rigging. Popular sentiment in Metro Manila sided with Aquino, leading to a massive, multisectoral congregation of protesters, and the gradual defection of the military to Aquino led by Marcos' cronies, Enrile and Ramos. It must be noted that prior to his defection, Enrile's arrest warrant, having been charged for graft and corruption, was about to be served. The "People Power movement" drove Marcos into exile, and installed Corazon Aquino as the new president. At the height of the revolution, Enrile revealed that his ambush was faked in order for Marcos to have a pretext for imposing martial law. However, Marcos maintained that he was the duly-elected and proclaimed President of the Philippines for a fourth term.

Exile and Death

The Marcos family and their associates went into exile in Hawaii and were later indicted for embezzlement in the United States. After Imelda Marcos left Malacañang Palace, press reports worldwide took note of her lavish wardrobe, which included over 2500 pairs of shoes.

Marcos died in Honolulu on September 28, 1989 of kidney, heart, and lung ailments. The Aquino government refused to allow Marcos's body to be brought back to the Philippines. He was interred in a private mausoleum at Byodo-In Temple on the island of Oahu, visited daily by the Marcos family, political allies, and friends. The body was only brought back to the Philippines four years after Marcos's death, during the term of President Fidel Ramos. From 1993 to 2016, his remains were interred inside a refrigerated crypt in Ilocos Norte, where his son, Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. ("Bongbong"), and eldest daughter, Maria Imelda Marcos ("Imee"), became the local governor and representative respectively. On November 18, 2016, the remains of Marcos were buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Cemetery of (the) Heroes), a national cemetery in Manila, despite opposition from various groups. In 2021, Bongbong Marcos announced that he would run for president of the Philippines in the 2022 election.

Imelda Marcos was acquitted of embezzlement by a U.S. court in 1990, but in 2018 she was convicted of corruption charges for her activities during her term as governor of Metro Manila.

In 1995 some 10,000 Filipinos won a U.S. class-action lawsuit filed against the Marcos estate. The charges were filed by victims or their surviving relatives for torture, execution and disappearances. Human rights groups place the number of victims of extrajudicial killings under martial law at 1,500 and Karapatan (a local human rights group's) records show 759 involuntarily disappeared (their bodies never found).

Legacy

President Marcos's official Malacañang Palace portrait since 1986; the portrait he had selected for himself was lost during the People Power Revolution Prior to Marcos, Philippine presidents had followed the path of "traditional politics" by using their position to help along friends and allies before stepping down for the next "player." Marcos essentially destroyed this setup through military rule, which allowed him to rewrite the rules of the game so they favored the Marcoses and their allies.

His practice of using the politics of patronage in his desire to be the "amo" or godfather of not just the people, but the judiciary, legislature and administrative branches of the government ensured his downfall, no matter how Marcos justified it according to his own philosophy of the "politics of achievement." This practice entailed bribery, racketeering, and embezzlement to gain the support of the aforementioned sectors. The 14 years of his dictatorship, according to critics, have warped the legislative, judiciary and the military.[10]

Another allegation was that his family and cronies looted so much wealth from the country that to this day investigators have difficulty determining precisely how many billions of dollars have been salted away. The Swiss government has also returned US$684 million in allegedly ill-gotten Marcos wealth.

His apologists claim Marcos was "a good president gone bad," that he was a man of rare gifts - a brilliant lawyer, a shrewd politician and keen legal analyst with a ruthless streak and a flair for leadership. In power for more than 20 years, Marcos also had the very rare opportunity to lead the Philippines toward prosperity, with massive infrastructure he put in place as well as an economy on the rise.

However, he put these talents to work by building a regime that he apparently intended to perpetuate as a dynasty. Among the many documents he left behind in the Palace, after he fled in 1986, was one appointing his wife as his successor.

Opponents state that the evidence suggests that he used the communist threat as a pretext for seizing power. However, the communist insurgency was at its peak during the late 1960s to early 1970s when it was found out that the People's Republic of China was shipping arms to support the communist cause in the Philippines after the interception of a vessel containing loads of firearms. After he was overthrown, former Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile stated that certain incidents had been contrived to justify the imposition of Martial Law.[11]

The Martial Law dictatorship may have helped boost the communist insurgency's strength and numbers, but not to the point that could have led to the overthrow of the elected government. Marcos' regime was crucial in the United States' fight against communism and its influences, with Marcos himself being a staunch anti-communist. Marcos however had an ironically mild streak to his "strongman" image, and as much as possible avoided bloodshed and confrontation.

His most ardent supporters claim Marcos was serious about Martial Law and had genuine concern for reforming the society as evidenced by his actions during the period, up until his cronies, whom he entirely trusted, had firmly entrenched themselves in the government. By then, they say he was too ill and too dependent on them to do something about it. The same has been said about his relationship with his wife Imelda, who became the government's main public figure in light of his illness, by then wielding perhaps more power than Marcos himself.

It is important to note that many laws written by Marcos are still in force and in effect. Out of thousands of proclamations, decrees and executive orders, only a few were repealed, revoked, modified or amended. Few credit Marcos for promoting Filipino culture and nationalism. His 21 years in power with the help of U.S. massive economic aid and foreign loans enabled Marcos to build more schools, hospitals and infrastructure than any of his predecessors combined.[12] Due to his iron rule, he was able to impose order and reduce crime by strict implementation of the law. The relative economic success that the Philippines enjoyed during the initial part of his presidency is hard to dispel. Many of Marcos' accomplishments were overlooked after the so-called "People Power" EDSA Revolution, but the Marcos era definitely had accomplishments in its own right.

On the other hand, many despise his regime, his silencing the free press, his curtailing of civil liberties such as the right to peaceably assemble, his dictatorial control, the imprisonment, torture, murder and disappearance of thousands of his oppositionists, and his supposed shameless plunder of the nation's treasury. It is quite evident that the EDSA Revolution left the Philippine society polarized. Nostalgia remains high in parts of the populace for the Marcos era due to the downward spiral the Philippines fell into after his departure. It can be said that his public image has been significantly rehabilitated after worsening political and economic problems that have hounded his successors. The irony is that these economic troubles are largely due to the country's massive debts incurred during his administration. The Marcos Era's legacy, polarizing as it is, remains deeply embedded in the Philippines today.

Writings

- Today's Revolution: Democracy (1971)

- Marcos' Notes for the Cancun Summit, 1981 (1981)

- Progress and Martial Law (1981)

- The New Philippine Republic: A Third World Approach to Democracy (1982)

- An Ideology for Filipinos (1983)

- Toward a New Partnership: The Filipino Ideology (1983)

Notes

- ↑ Manuel A. Caoili, “The Philippine Congress and the Political Order,” Philippine Journal of Public Administration Vol. XXX (1) (January, 1986): 21.

- ↑ Hartzell Spence, For Every Tear a Victory: The Story of Ferdinand E. Marcos (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969), 359.

- ↑ Ferdinand Marcos, Today's Revolution: Democracy (Ferdinand E. Marcos, 1971), v.

- ↑ Aquino vs. Enrile, 59 SCRA 183, Concurring Opinion of Justice Cecilia Muñoz Palma citing issues of the Manila Times on October 1,3,4,5,8,13,23 and 24, 1970.

- ↑ Proclamation No. 1081, Proclaiming a State of Martial Law in the Philippines Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ First Address to the Nation Under Martial Law Radio-TV Address of President Marcos, September 23, 1972. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ Augusto Caesar Espiritu, How Democracy Was Lost: A Political Diary of the Constitutional Convention of 1971-1972 (Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1993, ISBN 9789711005337).

- ↑ In Sanidad vs. Comelec, L-44640, October 12, 1976 the Supreme Court ruled that on the basis of absolute necessity both the constituent power (the power to formulate a Constitution or to propose amendments or revision to the Constitution and to ratify such proposal, which is exclusively vested to the National Assembly, the Constitutional Convention, and the electorate) and legislative powers of the legislature may be exercised by the Chief Executive.

- ↑ The Batasang Bayan was temporarily provided in the 1973 Constitution after the rejection of the convening of the Interim National Assembly in the referendum-plebiscite of October 16-17, 1976. Its constitutionality was approved by the Supreme Court.

- ↑ Carle H. Lande and Richard Hooley, Aquino Takes Charge Foreign Affairs, Summer 1986. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ Enrile admits military abuse, arrests under martial law CNN Philippines, October 22, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ Leodivico Cruz Lacsamana, Philippine History and Government (Phoenix Publishing House, 2001, ISBN 978-9710618941).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abaya, Hernando. The Making of a Subversive: a Memoir. Quezon City: New Day, 1984. ISBN 9711001543

- Aquino, Belinda (ed.). Cronies and Enemies: the Current Philippine Scene. University of Hawaii, 1982. ASIN B000N448P6

- Bonner, Raymond. Waltzing with a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy. New York: Times Books, 1987. ISBN 0812913264

- Celoza, Albert F. Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1997. ISBN 027594137X

- Espiritu, Augusto. How Democracy was Lost: A Political diary of the 1971-72 Constitutional Convention. Quezon City: New Day, 1993. ISBN 9711005336

- Gleek, Davis, Jr. President Marcos and the Philippine Political Culture. Cellar Book Shop, 1988. ISBN 978-9719107408

- Hamilton-Paterson, James. America's Boy: A Century of Colonialism in the Philippines. New York: Henry Holt, 1999. ISBN 0805061185

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz. Philippine History and Government. Phoenix Publishing House, 2001. ISBN 978-9710618941

- Marcos, Ferdinand. Today's Revolution: Democracy. Ferdinand E. Marcos, 1971. ASIN B0006C73RU

- Marcos, Ferdinand. Notes on the New Society of the Philippines. 1973.

- Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos. Ateneo De Manila Univ Press, 2017. ISBN 978-9715507813

- McCoy, Alfred. Closer than Brothers: Manhood at the Philippine Military Academy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 0300077653

- McCoy, Alfred. Dark Legacy: Human Rights Under the Marcos Regime. speech at the Ateneo University, Sept. 20, 1999.

- Romulo, Beth Day. Inside the Palace: The Rise and Fall of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. New York: Putnam, 1987. ISBN 0399132538

- Salonga, Jovito. Presidential Plunder: The Quest for Marcos Ill-gotten Wealth. Manila: Regina Pub. Co., 2001. ISBN 978-9718567296

- Spence, Hartzell. For Every Tear a Victory: The Story of Ferdinand E. Marcos. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964. ASIN B0006BM87Q

- Seagrave, Sterling. The Marcos Dynasty. New York: Harper & Row, 1988. ISBN 0060158158

- Vizmanos, Danilo. Through the Eye of the Storm. Manila: Ken Inc., 2000. ISBN 9718558411

External links

All links retrieved March 26, 2024.

- Hunt for tyrant's millions leads to former model's home The Sydney Morning Herald, July 4, 2004.

- Philippines loses out on Marcos millions BBC News, February 1, 2002.

- Philippine cult idolises Marcos BBC News, December 8, 1999.

- Philandering dictator added Hollywood star to conquests The Sydney Morning Herald, July 4, 2004.

- Philippines blast wrecks Marcos bust BBC News, December 29, 2002.

- Was Ferdinand Marcos the Best President of the Philippines? Emmanuel Alejandro.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.