Jean-François Champollion (December 23, 1790 – March 4, 1832) was a French classical scholar, philologist, orientalist, and Egyptologist, famous for deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Champollion was a gifted linguist, and his work on the Rosetta Stone opened the way for translation of the writings from the culture of ancient Egypt. For this, he is often regarded the Father of Egyptology.

Given the significance of Egyptian culture in the development of human history, Champollion's work was a major contribution to our knowledge of the past. Based on such understanding of past successful civilizations, we can better develop human society in the future.

Life

Jean-François Champollion was born on December 23, 1790 in Figeac, France, the last of seven children (two of whom were dead before his birth) of Jacques Champollion and Jeanne Françoise. He lived in Grenoble for several years, completing his basic education at the Lyceum in Grenoble. Even as a child he showed an extraordinary linguistic talent. By the age of 16, he had mastered several languages and had read a paper before the Grenoble Academy concerning the Coptic language. By 20, he could already speak Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Amharic, Sanskrit, Avestan, Pahlavi, Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean, Persian, and Chinese, in addition to his native French.

Champollion attended the College de France (1807-09), where he specialized in Oriental languages. By the age of 19, he had earned his Doctor of Letters degree. In 1809, he became assistant-professor of history at Grenoble, continuing to teach there until 1816. In 1812, he married Rosine Blanc, with whom he had one daughter, Zoraide (born 1824). He accepted, in 1818, an invitation to the chair in history and geography at the Royal College of Grenoble (1818-21).

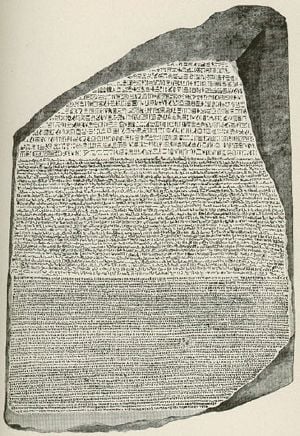

Champollion’s vast interest in Egyptology was originally inspired by Napoleon's Egyptian Campaigns 1798-1801. In 1799, French soldiers discovered the Rosetta Stone in Egypt, and numerous archaeologists unsuccessfully tried to decipher the script. Champollion’s knowledge of oriental languages, especially Coptic, led to his being entrusted with the task of deciphering the writing. He spent the years 1821–1824 on this task, finally managing to translate the text. His 1824 work Précis du système hiéroglyphique gave birth to the modern field of Egyptology. Champollion was appointed, in 1826, conservator of the Louvre Museum’s Egyptian collection, opened to the public in 1827.

In 1828 and 1829, Champollion led the joint Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt, together with Ippolito Rosellini, the professor of Oriental Languages at the University of Pisa and a student of Champollion. They traveled upstream along the Nile River and studied a large number of monuments and inscriptions. The expedition led to a posthumously-published extensive Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie (1845). Unfortunately, Champollion's expedition was blemished by instances of unchecked looting. Most notably, while studying the Valley of the Kings, he irreparably damaged KV17, the tomb of Seti I, by physically removing two large wall sections with mirror-image scenes. The scenes are now, together with numerous other artifacts, in the collections of the Louvre and the museum of Florence, Italy.

Champollion was subsequently made, first in 1830, a member of the Academie des Inscriptions, and then one year later, professor of Egyptology at the Collège de France, occupying the first chair of Egyptian history and archaeology, created just for him. He however did not have time to enjoy his new status. Exhausted by his hard labor during and after his scientific expedition to Egypt, Champollion died of a stroke in Paris in 1832, at the age of 41. He was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery.

Work

Champollion is generally credited as the father of Egyptology, and the person who deciphered the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone. However, the important groundwork in this area was previously been laid by two Britons: Thomas Young and William Bankes.

It was Thomas Young who worked on and who had partly succeeded in deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphs. By 1814, he had completely translated the "enchorial" (demotic, in modern terms) text of the Rosetta Stone, and a few years later had made considerable progress towards an understanding of the hieroglyphic alphabet.

Champollion continued Young’s work. Already in 1808, he had demonstrated that 15 signs of the demotic script corresponded to alphabetic letters in the Coptic language. In 1818, he concluded that some signs in the demotic script were in fact phonemes, and thus that the Egyptian script was only partially alphabetic.

Champollion’s next important finding was the recognition of the name “Ptolemy.” The Rosetta Stone was inscribed with three parallel inscriptions in hieroglyphs, demotic, and Greek language. By comparing the texts, Champollion was able to translate the name “Ptolemy,” thus deciphering several signs. In 1821, he also deciphered the word “Cleopatra,” he had twelve characters to work with, and finally was able to translate the rest of the text.

Champollion revealed his findings to the secretary of the French Académie des Inscriptions in 1822, when he wrote his Lettre à M. Dacier. Based on this letter he published a book in 1824 entitled Précis du système hiéroglyphique.

When Champollion published his translation of the hieroglyphs, Young praised his work, but also claimed that Champollion had based his system on Young's articles and wanted his contribution to be recognized. Champollion, however, was unwilling to share the credit. In the forthcoming schism, strongly motivated by the political tensions of that time, the British supported Young and the French Champollion. Champollion, whose complete understanding of the hieroglyphic grammar showed some mistakes made by Young, maintained that he alone had deciphered the hieroglyphs. However, after 1826, he did offer Young access to demotic manuscripts in the Louvre, when he was a curator there.

In 1828, Champollion led the Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt. This was the first time, after Napoleon’s expeditions to Egypt, that an expedition was sent to systematically survey the history and geography of Egypt through exploring the ancient monuments and their inscriptions. The expedition was followed with great interest, and Champollion’s reports were published on daily basis. After his death, the notes and sketches from this expedition were used by Karl Richard Lepisus and John Gardner Wilkinson in their fieldwork in Egypt.

Legacy

Champollion is credited with deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics through his translation of the Rosetta Stone, and thus giving us the insight into the culture and history of ancient Egypt. His expedition to Egypt was the first systematic effort to survey the monuments and their inscriptions of this area, and to provide scholars with the basic understanding of Egyptian culture. As his work laid the foundation for future research, Champollion is regarded as the father of Egyptology.

Publications

- Champollion, J.F. [1824] 2006. Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0543941566

- Champollion, J.F. [1833] 2001. Lettres écrites d'Égypte et de Nubie, en 1828 et 1829. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0543967735

- Champollion, J.F. 1973. A la memoire de Champollion. Impr. de l'Institut francais d'archeologie orientale.

- Champollion, J.F. 1974. Notices descriptives. Geneva: Editions de Belles-Lettres.

- Champollion, J.F. 1984. Principes généraux de l'écriture sacrée égyptienne: Appliquée à la représentation de la langue parlée. Paris: M. Sidhom. ISBN 2905304006

- Champollion, J.F. 1985. L'essentiel de l'orthographe. Secalib. ISBN 2867970210

- Champollion, J.F. 1986. Panthéon égyptien: Collection des personnages mythologiques de l'ancienne Egypte. Perséa. ISBN 2906427004

- Champollion, J.F. 1990. Monuments de l'Égypt et de la Nubie. Paris: Robert Laffont.

- Champollion, J.F. 1995. Les Vieux remèdes Bretons. Ouest-France. ISBN 2737318076

- Champollion, J.F. 2001. Egyptian Diaries. Gibson Square Books Ltd. ISBN 1903933021

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baussier, Sylvie. 2002. Champollion et le Mystère des hieroglyphs. Paris: Sorbier. ISBN 2732037486

- Dorra, Max. 2003. La Syncope de Champollion. Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 2070767930

- Honour, Alan. 1966. The man who could read stones: Champollion and the Rosetta Stone. Hawthorn Books.

- Jacq, Christian. 2004. Champollion the Egyptian. Pocket Books. ISBN 0671028561

- Lacouture, Jean. 1988. Champollion: Une vie de lumières. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2253057533

- Meyerson, Daniel. 2005. The Linguist and the Emperor: Napoleon and Champollion's Quest to Decipher the Rosetta Stone. Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 0345448723

- Reeves, N., and R.H. Wilkinson. 1996. The complete Valley of the Kings. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500050805

- Singh, Simon. 2000. The Code Book: The science of secrecy from ancient Egypt to quantum cryptography. Anchor. ISBN 0385495323

- Warren, John. Jean Francois Champollion: The Father of Egyptology. TourEgypt.net. Retrieved December 22, 2006.

External links

All links retrieved April 15, 2018.

- How to read Egyptian hieroglyphics - The pronunciation of the Ancient Egyptian language by Kelley L. Ross.

- Jean-François Champollion – Biography on BBC website.

- Key words: Unlocking lost languages – review of "The Keys of Egypt" by Lesley and Roy Atkins about Champollion’s work on Rosetta Stone.

- Rosetta Stone – What is Rosetta Stone?

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.