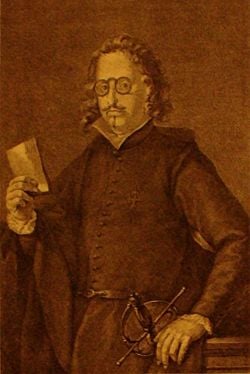

Francisco de Quevedo

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Villegas (September 17, 1580 - September 8, 1645) was a Spanish writer during the Siglo de Oro, the Golden Era of Spanish Literature. Considered a master of the elaborate style of baroque Spanish poetry, Quevedo is one of the most gifted poets to have lived in what remains the high watermark of Spanish literary production. Quevedo's style, which relied on the use of witty conceits and elaborate metaphors, is reflective of his own somewhat cynical attitudes towards literature as a whole; Quevedo was fiercely distrustful of excessively complicated literature, and he attempted to introduce a style of poetry that was, for his time, remarkably clean and concise.

A gifted novelist as well, Quevedo was notorious as a master satirist, and he used his considerable talent for mockery to defame his artistic competition. As with many capable of satire and simultaneously blessed with God-given talent, Quevedo seemed also prone to point criticisms outward, including allowing this to develop into less than respectful relationships with contemporaries.

Life and Work

Quevedo was born in 1580 to a family of wealth and political distinction. Raised in an upper-class atmosphere, Quevedo's early life was largely free of the troubles and conflicts that were to plague him as an adult. At the age of 16 he entered the University of Alcalá. He continued his studies for ten years, transferring halfway through his educational career to the University of Valladolid. By the time of his graduation Quevedo was a master of French, Italian, English, and Latin, as well as his native Spanish, and he had also acquired a reputation among his classmates for his scathing wit and gifts for versification.

By the time he had graduated from college, Quevedo's earliest poems, published when he was still a student, had attracted the attention of Miguel de Cervantes and Lope de Vega, elder luminaries of Spanish literature who both wrote Quevedo letters of praise and encouraged him to pursue career as a poet. Although he was flattered, Quevedo was not interested in a literary life. For more than ten years, Quevedo would instead fruitlessly pursue a career in politics, dreaming of becoming a member of the Spanish nobility.

Much of Quevedo's life as a man of political intrigue circled around the Duke de Osuna, an influential nobleman who was the acting viceroy of Sicily and Naples. By 1613, after seven years of devoted service, Quevedo had effectively become Osuna's closest confidante. Osuna had political aspirations of his own and the duke dreamed of subverting the democratic government of Venice and seizing control of the city for himself. Although the Spanish crown had secretly encouraged the duke, when the conspiracy to take over Venice failed, the government of Spain did everything in its power to distance itself from the scandal. Osuna endured a spectacular fall from grace from which he never recovered. Quevedo, who had been Osuna's main operative in Venice, was disillusioned from politics and devoted the rest of his life to writing.

Perhaps feeling spurned by the failure of his political aspirations, much of Quevedo's writings immediately after the collapse of the Osuna plot consisted of ferocious, satirical poems attacking many of the literary styles of his day. More than anyone else, Quevedo singled out Luis de Gongora for constant satire.

Gongora was the father of the literary style known as culteranismo, a movement unique to Spanish Renaissance poetry that attempted to revive the tone and syntax of ancient Latin poetry in the Latinate Spanish language; Quevedo ruthlessly attacked Gongora for his archaisms, his tortured sentences, and his strained metaphors. These criticisms apply more to Gongora's inept imitators than to Gongora himself, but which nevertheless stuck. The two men would bicker fiercely and publicly until Gongora's death in 1627.

In contrast to Gongora, Quevedo pioneered a style he called conceptismo, where a poem began from concepto (conceit) that would be expanded into an elaborate, fanciful and witty metaphor that would extend across the length of the poem. The style is quite similar to the near-contemporaneous Metaphysical poetry of English poets such as John Donne. Unlike Donne and the metaphysical poets, however, Quevedo was a resolutely secular poet. Most of his poems are satires of contemporary events and, therefore, largely inaccessible to a general audience. Those beautiful few that take a more serious turn are dominated by themes of romantic love and earthly beauty, such as the sonnet with the unwieldy title Dificulta el retratar una grande hermosura, que se lo habÃa mandado, y enseña el modo que sólo alcanza para que fuese posible ("Painting a great beauty, which he was asked to do, is hard, and he shows the only way it might be possible"):

|

|

In addition to sonnets such as the ones above, which were published in the volume Los sueños (Dreams), Quevedo is also particularly remembered today for his novel Historia de la vida del Buscón llamado don Pablos (The Life Story of the Sharper, called Don Pablos) which is now considered one of the earliest examples of the picaresqueâor satiricalânovel that realistically and humorously depicted the seedy underside of Spanish city life. The novel is considered to be a precursor for the satirical novels of industrial life that would emerge in later centuries, such as the works of Charles Dickens, Honore de Balzac, and Jonathan Swift.

Late in his life, in 1641, Quevedo, still feeling the sting of Osuna's failure, attempted to vindicate the former duke. Quevedo prepared an anonymous poem that materialized under King Philip IV's napkin at breakfast, blasting the policies of Philip's all-powerful favorite, Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, Count-Duke of Olivares. Quevedo's famous wit, however, was impossible to disguise, and this act landed the poet under house arrest that lasted until Olivares' fall in 1643. He died two years later, his health having suffered significantly for the worse during his imprisonment. He is remembered by many as one of the greatest talents in the greatest age of Spanish literature.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Picaresque novel

- Historia de la vida del Buscón llamado don Pablos (âThe Life Story of the Sharper, called Don Pablos,â 1626; there are several early English translations)

Poetry

- Los sueños (âDreamsâ) (1627)

- La cuna y la sepultura (âThe Crib and the Graveâ) (1635)

- La culta latiniparla ("The Latin-prattling blue-stocking," mocking a female culteranist, 1631)

Against Luis de Góngora and Culteranismo:

- Aguja de navegar cultos ("A Compass-needle to navigate culteranos'")

Political works

- PolÃtica de Dios, gobierno de Cristo ("The Polity of God and Government of Christ") (1626)

- Vida de Marco Bruto (âThe Life of Marcus Brutusâ) (1632-1644)

- Execración contra los judÃos ("Execration Against the Jews") (1633)

Biography

- "Life of St. Thomas of Villanova

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.