Grammar school

| Schools |

|---|

| Education |

| History of education |

| Pedagogy |

| Teaching |

| Homeschooling |

| Preschool education |

| Child care center |

| Kindergarten |

| Primary education |

| Elementary school |

| Secondary education |

| Middle school |

| Comprehensive school |

| Grammar school |

| Gymnasium |

| High school |

| Preparatory school |

| Public school |

| Tertiary education |

| College |

| Community college |

| Liberal arts college |

| University |

A grammar school, a term most often used in the United Kingdom and Australia, is a secondary school in which a traditional academic curriculum is taught in preparation for university. In the past, subjects such as Latin and Greek were emphasized. Four distinct uses of the word can be noted, the first two referring to ordinary schools set up in the age before compulsory secondary education, and two referring to selective schools thereafter. Arguably the most well-known grammar schools were those of the Tripartite System (also known colloquially as the grammar-school system), which existed in England and Wales from the mid-1940s to the late 1960s, and still exists in Northern Ireland. Pupils are admitted at age 12 usually after an examination called the Eleven Plus Exam.

Grammar schools were established to provide an academic education for the most able irrespective of their social or economic background. While some continue to support the idea of selective education, with the academically gifted (at age eleven) receiving education appropriate for tertiary education at the university level while others receive vocational education or a general education, for many this system is regarded as elitist and socially divisive. Reform of the system in the latter part of the twentieth century, introduced the comprehensive school for all students and closed the majority of grammar schools. One result paradoxically was a significant decline in social mobility, as it became much rarer for children from a socially deprived background to go to the best universities. The problem is that many people think that a good academic education is better than a good vocational education. What is more important is that children receive an education that can best enable them to fulfill their potential.

History

In medieval times, the importance of Latin in government and religion meant there was a strong demand to learn the language. Schools were set up to teach the basis of Latin grammar, calling themselves "grammar schools." Pupils were usually educated up to the age of 14, after which they would look to universities and the church for further study.

Although the term scolae grammaticales did not enter common usage until the fourteenth century, the earliest schools of this type appeared from the sixth century, for example, the King's School, Canterbury (founded 597) and the King's School, Rochester (604). They were attached to cathedrals and monasteries, and taught Latin (the language of the church) to future priests and monks. Other subjects required for religious work might also be taught, including music and verse (for liturgy), astronomy and mathematics (for the church calendar), and law (for administration).

With the foundation of the ancient universities from the late twelfth century, grammar schools became the entry point to an education in the liberal arts, with Latin seen as the foundation of the trivium. The first schools independent of the church, Winchester College (1382) and Eton College (1440), were closely tied to the universities, and as boarding schools became national in character.

During the English Reformation in the sixteenth century, many cathedral schools were closed and replaced by new foundations using the proceeds of the dissolution of the monasteries. For example, the oldest extant schools in Wales were founded on the sites of former Dominican monasteries. Edward VI also made an important contribution to grammar schools, founding a series of schools during his reign (see King Edward's School), and James I founded a series of "Royal Schools" in Ulster, beginning with The Royal School, Armagh.

In the absence of civic authorities, grammar schools were established as acts of charity, either by private benefactors or corporate bodies such as guilds. Many of these are still commemorated in annual "Founder's Day" services and ceremonies at surviving schools.

Teaching usually took place from dawn to dusk, and focused heavily upon the rote learning of Latin. It would be several years before pupils were able to construct a sentence, and they would be in their final years at the school when they began translating passages. In order to encourage fluency, some schoolmasters recommended punishing any pupil who spoke in English. By the end of their studies, they would be quite familiar with the great Latin authors, as well as the studies of drama and rhetoric.[1]

Other skills, such as numeracy and handwriting, were neglected, being taught in odd moments or by traveling specialist teachers such as scriveners. Little attention was given to other classical languages, such as Greek, due to a shortage of non-Latin type and of teachers fluent in the language.

In England, pressure from the urban middle class for a commercial curriculum was often supported by the school's trustees (who would charge the new students fees) but resisted by the schoolmaster, supported by the terms of the original endowment. A few schools managed to obtain special Acts of Parliament to change their statutes, such as the Macclesfield Grammar School Act 1774 and the Bolton Grammar School Act 1788, but most could not. Such a dispute between the trustees and master of Leeds Grammar School led to a celebrated case in the Court of Chancery. After 10 years, Lord Eldon, then Lord Chancellor, ruled in 1805, "There is no authority for thus changing the nature of the Charity, and filling a School intended for the purpose of teaching Greek and Latin with Scholars learning the German and French languages, mathematics, and anything except Greek and Latin."[2]

During the Scottish Reformation, schools such as the Choir School of Glasgow Cathedral (founded 1124) and the Grammar School of the Church of Edinburgh (1128) passed from the control of the church to burgh councils, and the burghs also founded new schools.

In Scotland, the burgh councils were able to update the curricula of existing schools. As a result, Scotland no longer has grammar schools in any of the senses discussed here, though some, such as Aberdeen Grammar School, retain the name.[3]

Victorian grammar schools

The revolution in civic government that took place in the late nineteenth century created a new breed of grammar schools. The Grammar Schools Act 1840 made it lawful to apply the income of grammar schools to purposes other than the teaching of classical languages, but change still required the consent of the schoolmaster. The Taunton Commission was appointed to examine the 782 remaining endowed grammar schools. The Commission reported that the distribution of schools did not match the current population, and that provision was greatly varied in quality. Provision for girls was particularly limited. The Commission proposed the creation of a national system of secondary education by restructuring the endowments of these schools for modern purposes. After the Endowed Schools Act 1869, it became markedly easier to set up a school. Many new schools were created with modern curricula, though often retaining a classical core. At the time, there was a great emphasis on the importance of self-improvement, and parents keen for their children to receive a good education took a lead in organizing the creation of new schools.[4] Many took the title "grammar school" for historical reasons.

Grammar schools thus emerged as one part of the highly varied education system of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland before 1944. These newer schools tended to emulate the great public schools, copying their curriculum, ethos, and ambitions. Many schools also adopted the idea of entrance exams and scholarships for poorer students. This meant that they offered able children from poor backgrounds an opportunity for a good education.[5]

Grammar schools in the Tripartite System

The 1944, Butler Education Act created the first nationwide system of secondary education in England and Wales.[6] It was echoed by the Education (Northern Ireland) Act 1947. Three types of schools were planned, one of which was the grammar school, the other two being the Secondary modern school and the Technical school. Intended to teach an academic curriculum to intellectually able children who did well in their eleven plus examination, the grammar school soon established itself as the highest tier in the Tripartite System.

Two types of grammar school existed under the system. There were more than 2000 fully state funded "maintained" schools. They emulated the older grammar schools and sought to replicate the studious, aspirational atmosphere found in such establishments. Most were either newly created or built since the Victorian period.

In addition to those run fully by the state, there were 179 Direct Grant Grammar Schools. These took between one quarter and one half of their pupils from the state system, and the rest from fee-paying parents. They also exercised far greater freedom from local authorities, and were members of the Headmasters' Conference. These schools included some very old schools, encouraged to partake in the Tripartite System, and achieved the best academic results of any state schools. The most famous example of a Direct Grant Grammar was Manchester Grammar School.

Grammar school pupils were given the best opportunities of any schoolchildren. Initially, they studied for the School Certificate and Higher School Certificate, replaced in 1951, by General Certificate of Education examinations at O-level (Ordinary level) and A-level (Advanced level). In contrast, very few students at secondary modern schools took public examinations until the introduction of the less academic Certificate of Secondary Education (known as the CSE) in the 1960s.[7] Grammar schools possessed better facilities and received more funding than their secondary modern counterparts. Until the implementation of the Robbins Report in the 1960s, children from independent (public) schools and grammar schools effectively monopolized access to university. These schools were also the only ones that offered an extra term of school to prepare pupils for the competitive entrance exams for "Oxbridge"—Oxford and Cambridge universities.

Abolition of the Tripartite System

The Tripartite System was largely abolished in England and Wales in the decade between 1965, with the issue of Circular 10/65, and the 1976 Education Act. Most grammar schools were amalgamated with a number of other local schools, to form neighborhood Comprehensive schools, although a few were closed. This process proceeded quickly in Wales, with the closure of such schools as Cowbridge Grammar School. In England, implementation was more uneven, with some counties and individual schools resisting the change.[8]

Direct Grant Grammar Schools almost invariably severed their ties with the state sector, and became fully independent. There are thus many schools with the name "grammar," but which are not free. These schools normally select their pupils by an entrance examination and, sometimes, an interview. While many former grammar schools ceased to be selective, some of them retained the word "grammar" in their name. Most of these schools remain comprehensive, while a few became partially selective or fully selective in the 1990s.

The debate about the British Tripartite System continued years after its abolition was initiated, and evolved into a debate about the pros and cons of selective education in general.

Supporters of the grammar school system contend that intelligent children from poor backgrounds were far better served by the Tripartite System as they had an opportunity to receive a free excellent education and thus be able to enter the best universities. However there were many middle-class parents who were upset if their children didn't get into a grammar school. So the Comprehensive System was created with the intention of offering a grammar school-quality education for all. This did not materialize as a grammar school curriculum is not suitable for everyone. As a result, many pupils have been put off education by an inappropriate academic curriculum. With increasing concern about levels of classroom discipline, it is argued that comprehensive schools can foster an environment that is not conducive to academic achievement.[9] Bright children can suffer bullying for doing well at school, and have to justify their performance to their social group.[9] The grammar school, catering exclusively to the more able, is thus seen as providing a safer environment in which such children can attain academic success.

Many opponents of the Tripartite System argue that the grammar school was antithetical to social leveling.[9] A system that splits the population into the intelligent and the unintelligent based on a test at the age of 11 does not aid social integration. The tripartite system gave an extremely important role to the eleven plus. Those who passed were seen as successes, while those that failed were stigmatized as second class pupils. The merits of testing at age eleven, when children were at varying stages of maturity, has been questioned, particularly when the impact of the test on later life is taken into account. Children who developed later (so-called "late bloomers") suffered because there was inflexibility in the system to move them between grammar and secondary modern schools. Once a child had been allocated to one type of school or the other it was extremely difficult to have this assessment changed. A better way of framing the test would be as one deciding on a child's aptitude and thus guiding them into either an excellent academic education or an excellent vocational education.

One reason the debate over selective education, or the "grammar school debate," continued for so long is that it reflects important differences in views about equality and achievement. The problem was not so much that the grammar schools provided an excellent academic education which suited its pupils. It was that the education given to pupils at secondary modern schools was not well resourced and did not provide a curriculum that would give its pupils the kind of qualifications they would need after they left school. The effort to establish comprehensive schools, following the vision of those such as Anthony Crosland to end selectivity, failed to produce a successful educational system for all. One result paradoxically was a significant decline in social mobility as it became much rarer for children from a socially deprived background to go to the best universities.[10] Yet, for many,

The comprehensive ideal remains powerful. The belief that drove politicians like Crosland should drive us now. It is a passion that all children, from whatever background, are alike in their capacity to reason, to imagine, to aspire to a successful life. In the 60s this meant rejecting the flawed science and injustice of the 11-plus and it meant radical surgery for a system in which children's futures were, in large part, decided on one day when they were 11.[11]

The failure of the comprehensive system can be argued as more a failure of implementation than a wrong direction:

There was little agreement on what it meant to provide a high-quality education once children were inside the school gate. Schools tended to take on a single model, with little scope for developing distinctive character or mission. The creation of "good" middle-class and "bad" working-class comprehensive schools was not predicted. And parents and pupils were not at the heart of reform.[11]

In March 2000, the Education Secretary David Blunkett sought to close down the debate by saying "I'm desperately trying to avoid the whole debate in education concentrating on the issue of selection when it should be concentrating on the raising of standards. Arguments about selection are a past agenda."[12]

Contemporary grammar schools

By the 1980s, all of the grammar schools in Wales and most of those in England had closed or become comprehensive. Selection also disappeared from state-funded schools in Scotland in the same period.

England

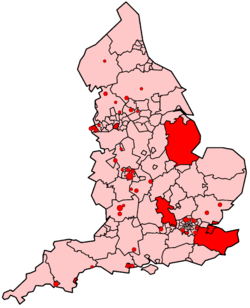

In the early years of the twenty-first century, there were still 164 state-run grammar schools in existence in England.[13] Only a few areas keep a formal grammar school system along the lines of the Tripartite System. In these areas, the eleven plus exam is used solely to identify a subset of children (around 25 percent) considered suitable for grammar education. When a grammar school has too many qualified applicants, other criteria are used to allocate places, such as siblings, distance or faith. Such systems still exist in Buckinghamshire, Rugby and Stratford districts of Warwickshire, the Salisbury district of Wiltshire, Stroud in Gloucestershire, and most of Lincolnshire, Kent and Medway. Of metropolitan areas, Trafford and most of Wirral are selective.[14]

In other areas, grammar schools survive mainly as very highly selective schools in an otherwise comprehensive county, for example in several of the outer boroughs of London. In some LEAs, as few as two percent of 11 year olds may attend grammar schools. These schools are often heavily over-subscribed, and award places in rank order of performance in their entry tests. They also tend to dominate the top positions in performance tables.[15]

Since 1997, successive Education Secretaries have expressed support for an increase in selective education along the lines of old grammar schools. Specialist schools, advanced schools, beacon schools, and similar initiatives have been proposed as ways of raising standards, either offering the chance to impose selection or recognizing the achievements of selective schools.

Northern Ireland

Attempts to move to a comprehensive system (as in the rest of the United Kingdom) have been delayed by shifts in the administration of the province. As a result, Northern Ireland still maintains the grammar school system with most pupils being entered for the Eleven plus. Since the "open enrollment" reform of 1989, these schools (unlike those in England) have been required to accept pupils up to their capacity, which has also increased.[16]

By 2006, the 69 grammar schools took 42 percent of transferring children, and only 7 of them took all of their intake from the top 30 percent of the cohort.[17]

With the end of the eleven plus, a proposed new transfer point at age 14, with specialization of schools beyond that point, may offer a future role for grammar schools. Alternatively, a consortium of 25 grammar schools could run a common entry test for admissions, while others, such as Lumen Christi College, the top-ranking Catholic school, have plans to run their own tests.[18]

Australia

In Australia, "grammar schools" are generally high-cost Anglican Church of Australia schools, public schools in the sense of the Associated Public Schools of Victoria and the Associated Grammar Schools of Victoria. Those using the term "grammar" in their title are often the oldest Anglican school in their area. Examples of these include such schools as Camberwell Grammar School (1886), Caulfield Grammar School (1881), Geelong Grammar School (1855), and Melbourne Grammar School (1858). The equivalent of the English grammar schools are known as selective schools.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong developed its Secondary education largely based on the English schooling system, with single-sex education being widespread. Secondary schools primarily offering a traditional curriculum (instead of vocational subjects) were thus called grammar schools.

Notes

- ↑ The Guild School Association (2003), Educating Shakespeare. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ J.H.D. Matthews, The Register of Leeds Grammar School 1820-1896 (Leeds: Laycock and Sons, 1897).

- ↑ T. G. K. Bryce and Walter M. Humes (eds.), Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh University Press, 2003, ISBN 0748609806).

- ↑ Peter Gordon, "Some Sources for the History of the Endowed Schools Commission, 1869-1900" British Journal of Educational Studies 14 (3).

- ↑ Will Spens (1938), Secondary education with special reference to grammar schools and technical high schools, HM Stationery Office, London. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ↑ J.R. Hough, The Education System in England and Wales: A Synopsis (Loughborough University Press, 1991, ISBN 0946348065).

- ↑ Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, The story of the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE). Retrieved May 15, 2008 .

- ↑ Jörn-Steffen Pischke and Alan Manning, Comprehensive versus Selective Schooling in England in Wales: What Do We Know? Working Paper, April 2006.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kate Jackson, Grammar school debate: Are Grammar Schools Better? BBC Kent. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ Anne-Marie Brook, Raising Education Achievement and Breaking the Cycle of Inequality in the United Kingdom, Economics Department Working Papers, 633, 2008.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ruth Kelly, Beyond Crosland's vision, The Guardian, Wednesday March 30, 2005. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ BBC News, Grammar debate is a "past agenda." Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ UK Parlaiment Publications and Records, House of Commons Hansard, 16 July 2007: Columns 104W-107W. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ↑ David Jesson, The Comparative Evaluation of GCSE Value-Added Performance by Type of School and LEA. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ↑ Sian Griffiths, Grammars show they can compete with best, Sunday Times. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ↑ Eric Maurin and Sandra McNally, Educational Effects of Widening Access to the Academic Track: A Natural Experiment. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ Caitriona Ruane, Education Minister's Statement for the Stormont Education Committee. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ Lisa Smith, "Test" schools accept D grade pupils. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bryce, T. G. K., and Walter M. Humes (eds.). Scottish Education: Post-Devolution. Edinburgh University Press, 2003 (original 1999). ISBN 0748609806.

- Carlisle, Nicholas. A Concise Description of the Endowed Grammar Schools in England and Wales. Thoemmes Continuum, 2002. ISBN 978-1855069565.

- Curtis, Polly. Grammar schools fuelling social segregation, academics find. The Guardian (Friday February 1 2008). Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- Hough, J. R. The Education System in England and Wales: A Synopsis. Loughborough University Press, 1991. ISBN 0946348065.

- Naylor, Fred, and Roger Peach. The Truth About Grammar Schools. National Grammar Schools Association, 2005.

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

- Grammar schools have expanded

- National Grammar Schools Association

- Q and A: Advanced schools An article on advanced schools and other advanced sections of the English secondary system.

- Campaign for State Education

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Grammar_school history

- Grammar_schools_in_the_United_Kingdom history

- Debates_on_the_grammar_school history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.